DESIGN editorial

According to engineer and physicist Adrian Bejan, featured in this issue, everything designs itself. In his quest for design’s unifying theory Bejan posits that all things—natural or artificial— take shape to maximize efficiency for that which flows through them: vascular systems, rivers, cities, airports. But while we share the rudiments of design acumen with many species and processes, its only humans that have designs on the future. And who better to consider the future of design than Winy Maas. In this issue, Javier Arpa interviews Maas on his latest thinking about design’s capacity to make the world a better place and how this translates into design education.

In theory, we use design to improve the world, but in practice design can have the opposite effect. Sometimes it does both. Think of the combustion engine liberating us from toil only to give us climate change, or the production of fertilizers to grow cheap food only to pollute our rivers. Think of the absurdity of bottled water using more water in its production than it ultimately contains. Think of all of design’s detritus piling up in mega-landfills, which then themselves require design! In their A–Z of design ecology, Craig Bremner and Paul Rodgers sort through the trash and try to make sense of some of design’s many broken promises.

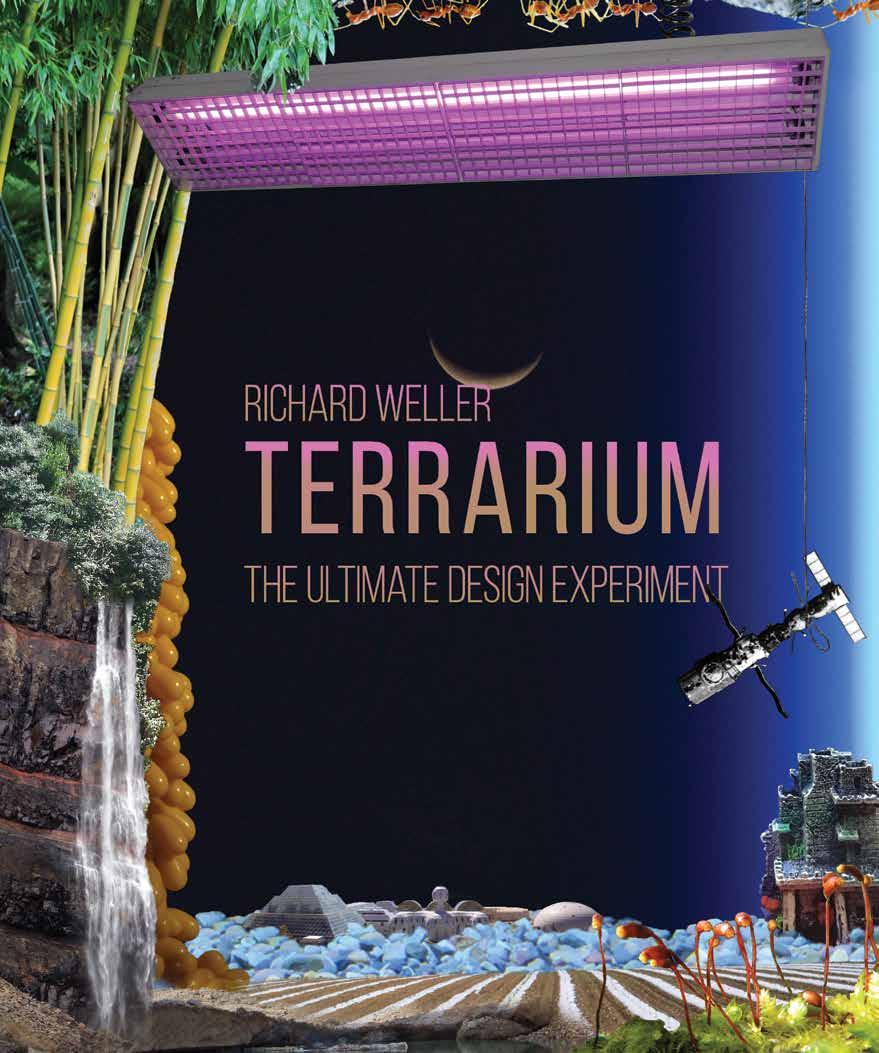

Whether we valorize it as the democratization of design or critique it as the perversion of the commodity fetish, designed things are now ubiquitous. Not only things, but entire systems must now be designed and objects reconceived and redesigned as mere moments in unfathomably complex ecological flows. Architects Lizzie Yarina + Claudia Bode explore this different and emerging conception of the object as part of systemic, relational assemblages. The discourse of the Anthropocene now frames the planet itself and even space beyond as a design problem. Looking through the metaphor of the terrarium darkly, Richard Weller revisits classic design failures such as Biosphere II and EPCOT arguing that at the heart of our tinkering with the world is a desire for total environmental control.

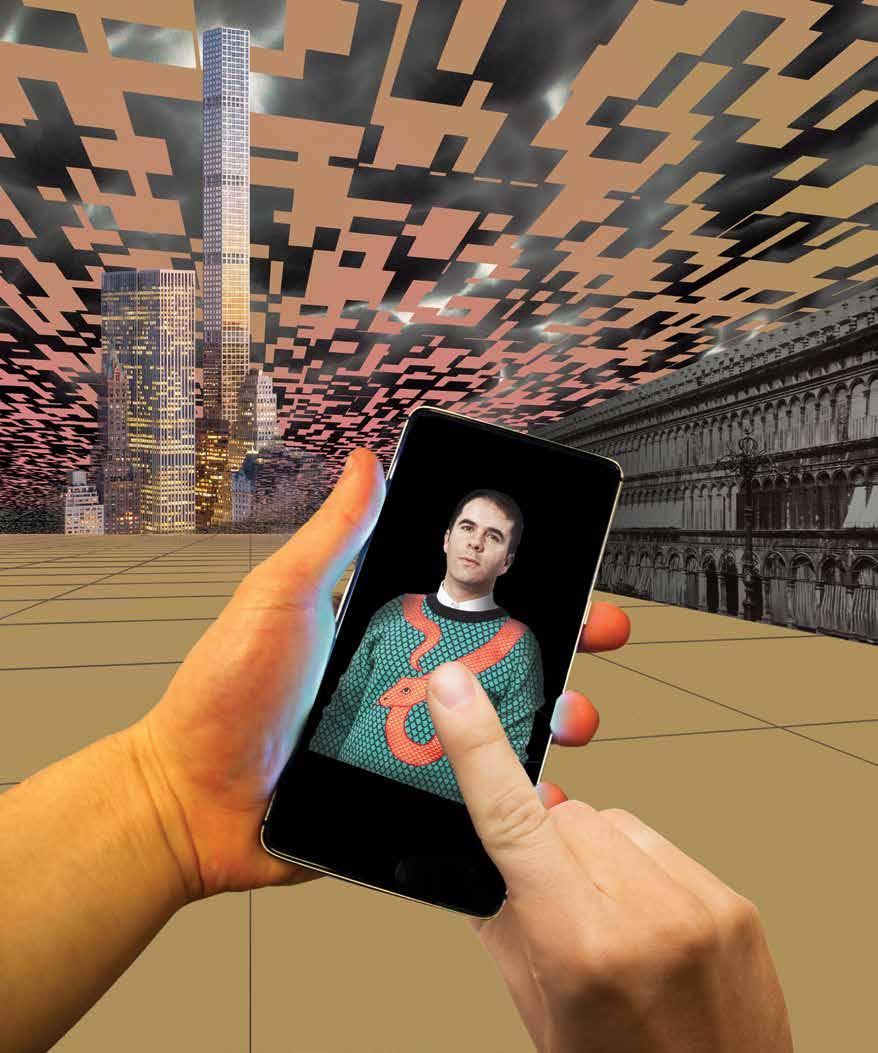

Environmental control is essentially now the domain of the digital. Design decisions are increasingly being made based on the available data, but what is often forgotten is that the data is never neutral. As such, designers not only need to become self-conscious about the ways in which data (mis)represents the world, but also actively and creatively engage in making their own data. Architect David Salomon opens up this issue and explores various methods of using data as both fact and fiction in relation to a selection of contemporary projects.

Design impacts lives and manifests certain world views. Design can serve the status quo or destabilize it. In short, design is

political. In this regard, Colin Curley interviews Andrés Jaque (Office for Political Innovation) who discusses the role of technology and agency of architecture in society today, and Christopher Marcinkoski interviews Anthony Dunne + Fiona Raby (Dunne + Raby) to discuss how their practice continuously seeks to redefine the role of design in society. The temple where such roles are showcased is the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, and for this issue Daniel Pittman interviews MoMA’s senior curator of architecture and design, Paola Antonelli, about new frontiers in the world of design.

Design is political, but it can also be fun and so we leave the museum to meet game designer Colleen Macklin who writes scripts for participatory games in New York’s public spaces. Macklin redefines and subverts public space through the agency of play. This playful psychogeography of the city is extended into the textuality of Los Angeles by anthropologist Keith Murphy who shows how different groups of people interact with and give meaning to the landscapes they inhabit. Design is also a question of desire, so moving further into the mind, experimental psychologist Thomas Jacobsen describes how current neurological research is coming closer to understanding the subjectivity of what individuals and cultures consider to be beautiful.

Finally, turning the microscope onto the profession of landscape architecture, James Corner discusses landscape architecture in relation to design culture, Jenni Zell explores life as a woman landscape architect through a Kafkaesque lens, while Thomas Oles challenges stereotypes of landscape architecture’s professional identity. And if design still seems like something only related to the aesthetic engines of New York, London, and Milan, we are pleased to publish Dane Carlson’s early work as he builds a different design career in the developing world.

In the call for papers for this issue we asked, what does landscape architecture bring to the broader culture of design? What lessons can be learned from other disciplines at the cutting edge of design? What role does design play in a time of transformative technological change? Here, then, are the answers, + some!

Tatum L. Hands + Richard Weller Issue Editors

+ IN CONVERSATION WITH Andrés Jaque

+ Your design work encompasses a spectrum of architecture interiors, film, exhibit design, teaching, and performance. How do these different methods of design exploration and production work together within your practice?

Andrés Jaque is founder and director of the Office for Political Innovation (Madrid and New York), and associate professor and director of the Master of Science program in Advanced Architectural Design at the Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation. His practice develops architectural projects that bring inclusivity into daily life. Through built works, performances, and exhibitions, his work instigates crucial debates for contemporary architecture. Recently, his research has explored dating apps and the role these technologies play in society. Colin Curley caught up with Andrés in New York on behalf of LA+ Journal.

It’s a very good question. The reason my practice is so diversified is because reality is diversified. So, in order to gain an agency and be relevant to architecture, I ended up doing many different things and connecting them. This is something that has two directions for me. One is towards the future: how I will reinvent daily life, society, and the world we live by (and I would say by, rather than in). That means that we have to reinvent space, but also connections, infrastructures, and performances and the way we understand them.

It also works backwards. By connecting all these different practices, we also can look back to our built architecture and realize that we could never really understand buildings without looking at the way they were used, the way they would perform, the way they were discussed, and the way things that happen at different scales came together through architecture. For me it’s been an adventure that was meant to help me gain an agency in the reinvention of daily life, but also helped me understand much better what architecture is about, and what it’s been about.

+ That's a good segue into what you explore through your practice. As the name of your practice, Office for Political Innovation, suggests, your work explores the broader social, societal, and political dimensions of architecture and the built environment. How do you define the politics of architecture within your practice, and engage them or work with them through your projects?

Often, we hear that architecture is about providing boxes or containers in which society can be accommodated. I’m totally against this notion because I believe architecture is a part of society, never a neutral container for it. It mediates between actors that are very different – for instance, between mountains or the atmosphere, and people, animals, or machines. What brings them together is architecture.

So, I believe architecture is a mediator that is never just neutral, but connects things with distinct qualities. We can define those qualities as political because they help define what gets connected and what remains disconnected, and because the act of mediation can only be described through terms like “alliance,” “sponsorship,” “association,” “confrontation,” and “dispute.” All these terms belong to the realm of politics.

But the politics I’m interested in are not the politics of political parties or spoken words. I’m interested in the politics that can be done through material devices or through performances: through design, in general terms. For instance, when we design a ramp, we make it possible for people with wheelchairs to access a location and participate in events that would otherwise be inaccessible. Those are the kinds of politics that I’m interested in: the ones that are done through ramps, through doors, through walls, through structures, through services, pipes, and lights. And that’s precisely what I would call material politics, or design politics. In the long run, these politics often gain much more importance than those of spoken words, and that’s why I think architecture is very exciting now – precisely because it’s political, but can be political in a very particular way.

Thomas Jacobsen is a professor of experimental and biological psychology at Helmut Schmidt University, Hamburg, Germany. He holds a PhD from the Max Planck Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience and is author of over 100 journal publications and two monographs in the area of neurocognitive psychology, including auditory processing, language, empirical aesthetics, and executive function. In 2008, Jacobsen received the Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten Award of the International Association of Empirical Aesthetics.

Often we prefer the more beautiful entity to the one that is less so. Great designs can help us feel elevated, or more at one with the world. At times, the beautiful item does not function well, yet still we prefer it. Sometimes preferences seem to be universal, and sometimes we argue a lot. The (neurocognitive) psychology of aesthetics seeks to describe and explain all of these phenomena. Rooted in today’s academic psychology and cognitive neuroscience, a wealth of methodological options is at our disposal. In fact, the psychology of aesthetics (or, as it has been termed, experimental aesthetics) is the second-oldest branch of experimental psychology.1 In 1876 Gustav Theodor Fechner applied experimental techniques to the study of aesthetic appreciation in a psychophysical way, and scholars have pursued this paradigm ever since.

Many determinants of aesthetic experience and behavior have been identified. It has been reported that aesthetic experience and judgments are affected by an object’s symmetry or asymmetry, complexity or simplicity, novelty or familiarity, proportion or composition, and protypicality, as well as the semantic content as opposed to formal qualities of design. In addition, many factors are known to influence aesthetic judgments, including aspects of a person’s emotional state, education, and historical, cultural or economic background, and the object’s appeal to social status or financial interest. Various situational aspects also play a role; for example, we might appreciate the same object differently in a museum compared to a supermarket. In addition, aesthetic judgment is also determined by inter-individual differences. These and other factors illustrate the fact that aesthetic experiences and behavior are subject to a complex network of stimulus-, person-, and situation-related influences.

The psychophysical study of aesthetics can be tested in relation to various areas, which may be best characterized via the seven perspectives shown in the adjacent chart. One perspective starts with the object of aesthetic appreciation: the various domains of aesthetics, like painting, sculpture, opera, theatre, architecture, design, and many more. In contrast to a subjective first-person view, features of the objects are being assessed and characterized. One example is the feature of symmetry, which has long been argued to be an important characteristic of beauty.

Opposite: The seven perspectives of the psychology of aesthetics.

In a series of studies since 2002, I and my research partners have employed the symmetry feature in our visual stimuli. Using functional MRI, we investigate the neural correlates of aesthetic judgments of beauty in response to visual stimuli of novel graphic patterns in a trial-by-trial cuing setting using binary responses (symmetric, not symmetric; beautiful, not beautiful).2 Symmetry, and of course all other features of objects, can be looked at assuming a diachronic

Psychology, Aesthetics, DESIGN

Person

Individual Di erences

Group Di erences

Expert / Non-Expert Di erences

Content

Painting Sculpture

Music Literature

Food

PSYCHOLOGY OF AESTHETICS

Body

Biology Neurosciences

Brain

Mind

Cognition

Emotion

Attitudes

Prototypes

Situation

Schemata Scripts

Diachronia

Biological Evolution

Cultural Evolution

Fashion Temporal Stability

Ipsichronia

Culture

Social Processes Sub-Culture

The Social World as Pattern/ed Language

Keith M. Murphy is associate professor of anthropology at the University of California, Irvine. He has conducted ethnographic research with architects in Los Angeles and furniture designers in Sweden, and is currently researching the cultural and political sides of typography in the United States. He is author of Swedish Design: An Ethnography (2015).

anthropology, DESIGN

I

t took a while, but anthropologists have at last discovered design. Since anthropology first emerged as the scholarly study of human beings in the late 19th century, many design-adjacent cultural forms like art, craft, and the built environment have featured prominently in the discipline’s research portfolio, but the “designed-ness” of these cultural forms has been mostly ignored. Instead, the surface meanings of those cultural forms have simply been read: art as reflecting social values, craft as demonstrating a mode of production, and built environments as offering local adaptations to various natural conditions. Of course cultural forms like these, or of all kinds really, don’t arise ex nihilo. They are made, significantly from the effort of human hands, minds, and voices, and it is this making, including designing and its potential complexities, that anthropologists have recently begun to explore more deeply.

Anthropological Designs

Most current understandings of design tend to treat designers as, to borrow Susan Sontag’s description of Swedish aesthetes, “pedants of the object,”1 that is, focused squarely on the details of the particular things they make, including what those things look like and how they work. This characterization is, undoubtedly, quite right in most instances. By comparison, an anthropological approach to design situates that object pedantry—and by “object” I mean, broadly, anything that’s designed for some purpose—in a much wider and more nuanced social context, and tries to explain not only how single objects, but also how entire assemblages of designed things come to compose what we experience as the everyday world. Put differently, anthropology offers a relational mode of analysis, a mode of understanding humans and things that foregrounds connections between the social world’s basic building blocks, be they of material, ideological, spatial, emotional, linguistic, or natural essences, without necessarily privileging one over the other. If we apply that approach to understanding design, we can say that while design practice does indeed entail the intentional manipulation of order and form in the traditional sense, it also involves working, arranging and distributing other matters (social orders and cultural forms), even in ways that extend beyond designers’ own pedantry of their objects.

To explain more fully what I mean by this claim, I want to examine some links between two phenomena, typography and landscape, each with its own designed features and each of which is a significant component of the everyday world. Before getting there, though, I’d like to say a bit more about what I mean by form.

Giving Form

A common aphorism applied to design (and in some languages, like Swedish, it’s a true synonym for the term) is “form-giving.” Typically form-giving is associated with physical or spatial forms—geometries, sizes, colors, and orders—and designers are treated as “giving” these forms “to” the specific

objects they create. Anthropology, too, is concerned with form, but in a much looser sense of the term. Basically, anything that holds a structure or configuration that’s recognizable and meaningful to members of some social group can count as a cultural form. A form can indeed be physical, like the shape of a certain architectural feature, or geometrical, like the symbol of the cross in Christianity, but it could also be a form of motion, like the moves of a particular ceremonial dance, or a form of habitation, like how gendered bodies are expected to occupy public space.

What’s critical for seeing design anthropologically is understanding how material, physical, and spatial forms meaningfully relate to, and help produce and cultivate, other kinds of cultural forms that collectively constitute the social world, even in cases that designers themselves don’t anticipate. Some of these relations are obvious, like how the distributions of walkways in a park produce forms of movement, and the placement of large shade trees alongside those walkways can provide zones of respite from the sun’s heat. Or how hostile design features, like skatestoppers and slanted public benches, are placed to prevent certain kinds of people from occupying certain kinds of spaces, thereby producing particular “good” and “bad” forms of inhabiting space (and also, “moral” and “not moral” kinds of people). But many of the forms brought forth by design are both more subtle and more complex, including forms of action and interaction, forms of discourse, forms of thought, and forms of social organization. This perspective requires attending to a much wider variety of forms than is typically associated with design, and also taking them seriously as forms, that is, as organized, consistently (if not uniformly) shaped, and regular.

Perhaps another way to think about this is through the lens of a pattern language. In A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction, Christopher Alexander and colleagues present and elaborate a “language” of titled and numbered entities, or patterns, that when used in combination both identify and offer solutions to a range of problems often experienced in the everyday world.2 What’s critical to this list is that the constitutive elements are, like the forms I’ve identified above, not all of the same nature. Some of the patterns are structural, like (17) Ring Roads, (21) Four-Story Limit, and (50) T Junctions. Others are more cultural, like (24) Sacred Sites, (58) Carnival, and (66) Holy Ground. Many explicitly concern social organization, like (36) Degrees of Publicness, (75) The Family, and (84) Teenage Society, while others are more focused on actions and interactions, like (63) Dancing in the Streets, (68) Connected Play, and (94)

Sleeping in Public. Several, like (40) Old People Everywhere and (79) Your Own Home, reflect a complex combination of types. What’s more, these patterns are scaled from very large, like (2) Distribution of Towns and (42) Industrial Ribbons, to very small, like (65) Birth Places and (74) Animals, and differently specified, from the mostly vague, like (9) Scattered Work and (10) Magic of the City, to very particular, like (20) Mini-Buses and (22) Nine Percent Parking.

For Alexander and his colleagues, this pattern language, a flexible network of sequentially linked forms, was primarily useful as a customizable tool to help designers puzzle through their own individual projects. However, because these patterns were originally derived from careful observation of the lived world, and because the language was assembled agnostically with regard to the “kind” and “nature” of the language’s constituent forms, the tool these architects came up with unexpectedly works as a sort of model for understanding design from an anthropological point of view.

Lettering the Land

Anthropologists have spent a lot of time studying how different groups of people interact with and give meaning to the landscapes they inhabit. Dwelling in and moving through space are of course significant modes of interaction with the land, but what anthropologists have long argued is that doing so is never neutral, and always mediated through the experience of cultural forms (like religious beliefs, gender norms, kinship), such that human relations with their environments are largely created and maintained though different webs of meaning. One of the most significant cultural forms that mediates people’s relationships with landscape is language, especially in its graphic guise, typography.

Probably the most obvious form that typography takes in urban public space, in a place like Los Angeles,3 for example, is in signage of different types. There are signs that mark businesses, with a name and a logo, and municipal signs that accomplish proxy-governmental functions, like officially designating a neighborhood, regulating speed, or establishing a particular agency’s jurisdiction. There are posters, billboards, and banners advertising events and services that aren’t necessarily linked to the space itself, but that might appeal to those who move through it. And on these different signs, or some of them at least, are different languages, signaling different sorts of things, though what’s signaled depends on the language. Maybe it’s that many speakers of a language

Richard Weller is Professor and Chair of Landscape Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania where he also holds the Martin and Margy Meyerson Chair of Urbanism. Weller is author of a number of books on design and regional planning including Boomtown 2050: Scenarios for a Rapidly Growing City (2009) and Made in Australia: The Future of Australian Cities (2014). His recently published Atlas for the End of the World (2017) documents global flashpoints between urbanization and biodiversity.

TECHNOLOGY, DESIGN

At some point in their education most kids will make a terrarium. An article in the US National Science Teachers Association’s journal, Science and Children, states that while a failed terrarium is a disappointment for the children, it is nonetheless “a good point of departure for discussion.”1 The 1975 article I am referring to doesn’t prescribe what that discussion should be, but we can infer that the failed terrarium lends itself to a cautionary tale about human manipulation of the environment. By contrast, the successful terrarium is a take-home trophy of getting at least some basic biological relationships right.

But by imprisoning, and eventually killing that which it appears to protect, the terrarium has a dark side. In the terrarium, nature is simultaneously reified by and cut off from culture. The terrarium lures the unsuspecting child into the conceptual framework of Cartesian dualism, a way of knowing the world that few will ever be able to escape. In this sense, making a terrarium rehearses in miniature the ominous environmental narrative of adulthood in the Anthropocene – an age where that ultimate terrarium, the Earth, is now fixed in the gaze of a thousand satellites. And like the child looking down upon their little world, the adults too are uncertain if the experiment they are conducting with theirs, will succeed or fail.

LA+ (Landscape Architecture Plus) from the University of Pennsylvania School of Design is the first truly interdisciplinary journal of landscape architecture. Within its pages you will hear not only from designers, but also from historians, artists, philosophers, psychologists, geographers, sociologists, planners, scientists, and others. Our aim is to reveal connections and build collaborations between landscape architecture and other disciplines by exploring each issue’s theme from multiple perspectives.

LA+ brings you a rich collection of contemporary thinkers and designers in two issues each year. To subscribe follow the links at www.laplusjournal.com.