Infinite Place

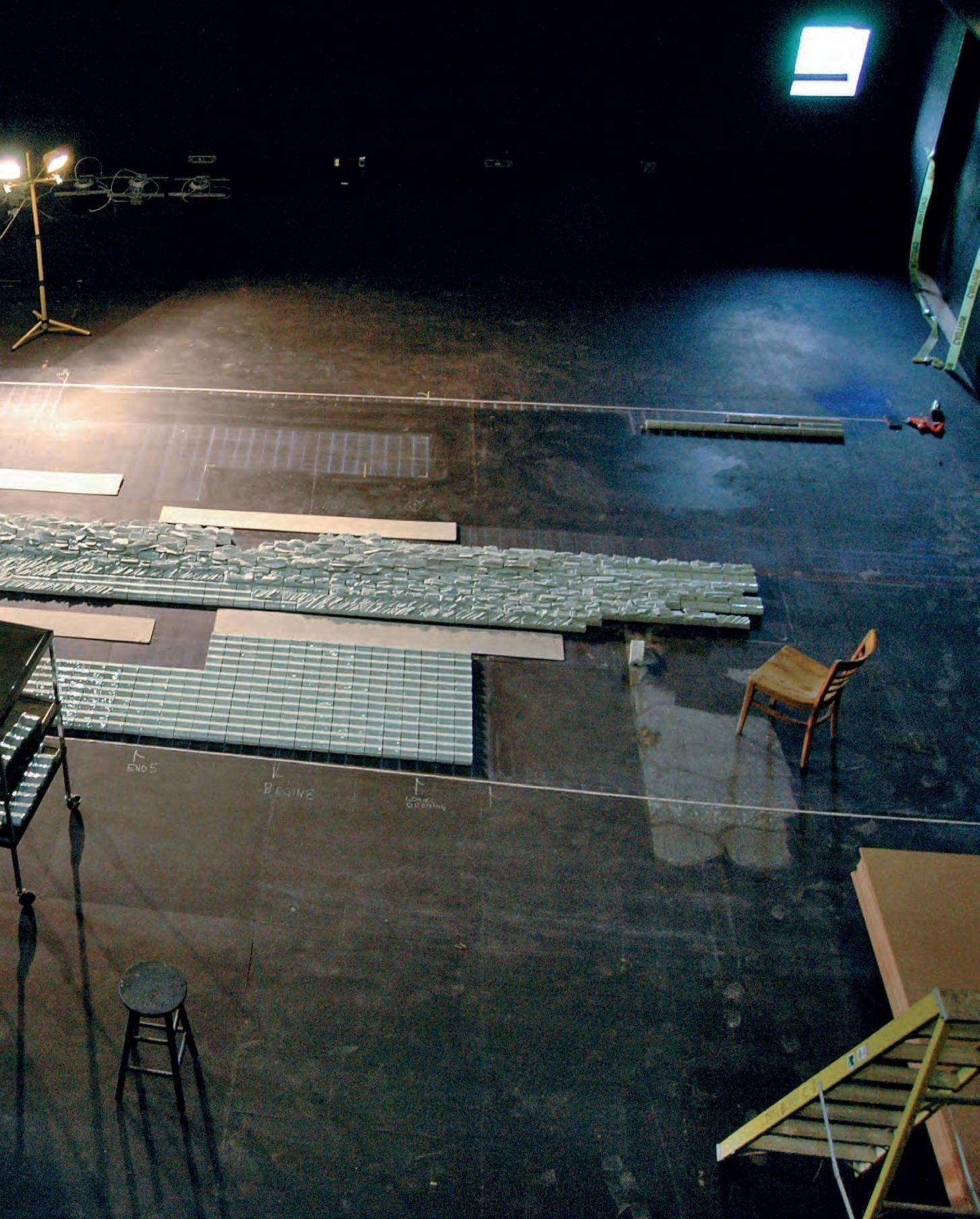

Portfolio—Multiple

Geographies of a Mind

PETE R HE LD

It is a pity indeed to travel and not get this essential sense of landscape values. You do not need a sixth sense for it. It is there if you just close your eyes and breathe softly through your nose; you will hear the whispered message, for all landscapes ask the same question in the same whisper. “I am watching you— are you watching yourself in me?”

Lawrence Durrell, 19691

Take a road that never ends

The rivers are long and piled high with rocks

The streams are wide and choked with grass

It’s not the rain that makes the moss thick And it’s not the wind that makes the pines moan Who can get past the tangles of the world And sit with me in the clouds.

Han Shan (Cold Mountain), circa 7502

Wayne Higby is a consummately self-aware artist whose reflections on his own work are at once poetic, profound, and unassailable. The arc of his career tests one’s grasp of how mind, space, and landscape coalesce. Early ascension placed him at the forefront of the American ceramics movement during an era of explosive growth and originality. It would be too simplistic to define him only as an innovator of raku-firing, although his iconic raku bowl forms made during the 1970s and 1980s are considered to be his signature works, his technique never gave primacy over content. As his story unfolds and as his breadth of work demonstrates, a broader perspective is needed for an artist equally committed to studio practice, and as well as his role as an educator, writer, and world traveler.

Defining Moments

Growing up in the foothills of Colorado Springs, Higby embraced the vast landscape of the American West. An only child, he found solace, joy, and mystery within the great outdoors with its craggy rock outcroppings, hidden caves, and majestic views of Pikes Peak. An acute observer with an intense curiosity, he found passion in youthful activities: horseback riding, high-school theater, and the arts. Classes taken at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center throughout his childhood provided an early outlet for his latent artistic talents. As he neared college, his father, a prominent local attorney involved in politics, tried to steer him toward a profession in law, but his son was doubtful this would be his chosen path. In 1961 he enrolled at the University of Colorado Boulder, where he concluded he was ill-suited to follow his father’s vocation. Pursuing his interest in the arts, he became an art major with the idea of being a painter.

In his junior year he took six months to travel with family friends, visiting Japan, Southeast Asia, India, Greece, and southern Europe. For someone who had led a sheltered childhood, it became shockingly apparent in Calcutta, India, that humanity was far broader than first imagined. A self-imposed four-day quarantine in his hotel room questioned his role in the world. In hindsight, the experience propelled him toward a vision of humanity and art, which paved his commitment to teaching.

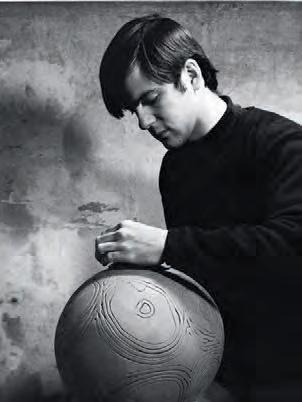

The group then traveled to Greece, which proved to be another epiphany that would encourage a lifetime in clay. Standing entranced in front of cases of Minoan pottery, Higby began to grasp the integration of painted motifs on three-dimensional forms. Ceramics never enter ed into his conversations with the art faculty prior to this experience, and when he returned, he sought out George Woodman, one of his professors who taught painting, drawing, and philosophy of art. Trying to assimilate and grasp the import of his enthusiasm for pottery, he was soon connected to George’s wife, the potter Betty Woodman. No better guide was possible, and Higby focused on ceramics during his last year at university (fig. 1). Meanwhile a visiting artist at Boulder, Manuel Neri, imparted new perspectives on the burgeoning West Coast ceramic movement, revealing the work of Peter Voulkos, Henry Takemoto, and

1 Wayne Higby, studio, 1968, Omaha, Nebraska.

INLAID L U STE R JAR , 1968. Glazed earthenware, raku-fired. 13 × 13 × 11 inches. Collection: Ford & University Galleries, Eastern Michigan University, Ypsilanti

08 GR EE N TE RR AC E CA NY ON , 1975. Glazed earthenware, raku-fired. 13 × 13 × 11 inches. Collection: Marlin and Regina Miller

09 D EE P C OV E , 1972. Glazed earthenware, raku-fired. 13 × 13 × 11 inches. Collection: David Owsley Museum of Art, Ball State University, Muncie, Indiana

Ceramics, the Vessel, and the Paragone Debate

T ANYA H ARROD

This essay tracks some postwar North American critical strategies in ceramics. By the late 1950s logic dictated ambitious clay work be brought into mainstream visual culture. A language would be forged through comparison and contrast with painting and sculpture. From the late 1950s onward, as a vocabulary for ceramics struggled to emerge, the writing was as vivid and as hopeful as the objects it attempted to dissect. The late 1970s, however, saw a call to order that took the form of a re-engagement with the past and with a multiplicity of ceramic traditions. In a historicist turn that was characteristic of aspects of postmodernism, writers and practitioners set about mapping a specifically ceramic aesthetic that focused on the vessel form and its global history. The aim was to resolve the problematic materiality of ceramic—in particular, its messy capacity to be anything

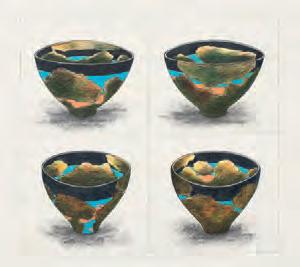

1 Study for Black Sky Landscape Bowl , 1987. Colored pencil on paper. 18 × 23 inches. Collection of the artist.

The first, comparative, approach of measuring art forms against each other had respectable historic antecedents. As was the case with postwar American ceramics, the so-called Paragone debates of sixteenth-century Italy were born of status wars, registering the uncertain standing of painting and sculpture by comparison with other intellectual and imaginative activities. Leonardo da Vinci, the Paragone’s most famous exponent, argued for the superiority of painting over sculpture and for painting’s equality with both poetry and music. The debate—which drew in many other Renaissance writers and artists—led to the creation of workable vocabularies with which to discuss di erent artistic genres. 1 For most of us, the Paragone debate belongs with Renaissance studies. But comparing and contrasting the strengths and qualities of di erent kinds of art remains a seductive exercise. More to the point, during and after the Second World War the Paragone was central to the trenchant writings of Clement Greenberg.

Greenberg set out to define and di erentiate, arguing in 1940 that innovative painting declared itself by its flatness and its “two-dimensional atmosphere,” while sculpture needed to radically reject representation in favor of construction devoid of historical associations.2 Greenberg explained that “purity in art consists in the acceptance, willing acceptance, of the limitations of the medium of the specific art.”3 Greenberg held on to the idea that sculpture and painting should maintain specific and self-referential identities. In 1949 he was arguing that sculpture o ered more possibilities than painting. Released from “mass and solidity,” sculpture could “say all that painting can no longer say.”4

By the 1950s his strictures on the autonomy of painting and sculpture were to harden into an unhelpful orthodoxy, and in any case the hybrid practice of artists like Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg—what Greenberg called “mediumscrambling”5—had begun to undermine his mantra of “pure painting” and “pure sculpture.” But, as a way of talking about an art form, the Paragone continued to have its uses, not least in generating a critical language. It was a way of getting at the essence of a genre and of mapping a shift in emphasis. For instance, the sculptor Donald Judd’s essay “Specific Objects” of 1965 was essentially a Paragone discussion in which what he termed “three-dimensional work” was measured against the sculpture and painting of the previous decade.6

1 For the clearest account see Catherine King, Di Norman, and Erika Langmuir, “The Paragone,” in Art in Italy 1480–1580 , Units 11–12 (Milton Keynes: Open University Press, 1979).

2 See W. J. T. Mitchell, “Architecture as Sculpture as Drawing: Antony Gormley’s Paragone,” in Antony Gormley: Blind Light (London: Hayward Gallery, 2007); Clement Greenberg, “Towards a Newer Laocoon” (1940), in Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism , ed. John O’Brien, vol. 1 (Chicago/London: University of Chicago Press, 1986), pp. 35, 36.

3 Greenberg 1986 (see note 2), p. 36.

4 Clement Greenberg, “The New Sculpture” (1949), in Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism , ed. John O’Brien, vol. 2 (Chicago/London: University of Chicago Press, 1986), p. 318.

5 Clement Greenberg, “The Status of Clay” (1979), in Ceramic Millennium: Critical Writings on Ceramic History, Theory, and Art , ed. Garth Clark (Halifax, Nova Scotia: Nova Scotia College of Art and Design Press, 2006), p. 4.

6 Donald Judd, “Specific Objects,” in Modern Sculpture Reader , eds. Jon Woods, David Hulks, and Alex Potts (Leeds: Henry Moore Institute, 2007), pp. 213–20.

2 Thomas Cole, The Titan’s Goblet , 1833. Oil on canvas, 19 ⅜ × 16 ⅛ inches. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gift of Samuel P Avery Jr., 1904.04.29.2. Image source: Art Resource, New York.

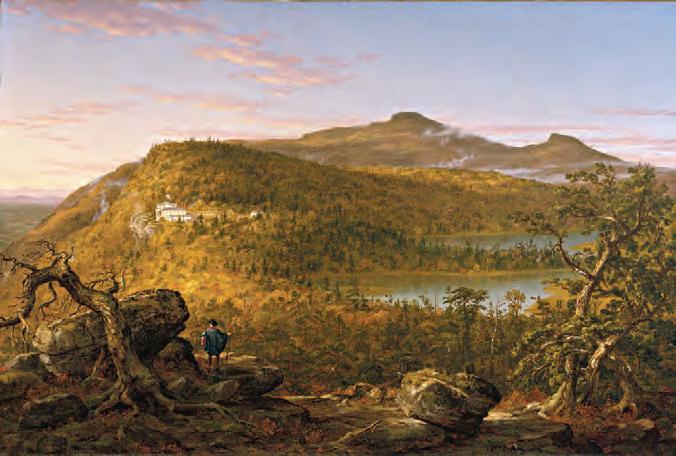

Intentionally or not, the arc of Preuss’s text serves to create a kind of three-dimensional space to his map, as if the text were itself the rim of a basin lying on its side across the western United States. And, intentionally or not, this great basin echoes in the actual landscape the other great basin of the day, Thomas Cole’s The Titan’s Goblet (fig. 2), one of the most mysterious paintings ever produced—in 1833—by America’s first great landscape painter.

Like Preuss’s basin, the scale of Cole’s goblet is enormous. Perched on the far rim of the goblet are a Greek temple and a Roman villa. Boats sail across its surface. No steady flow of water spills from its rim; rather, it appears windblown, overflowing the rim in gusts. When the painting was first exhibited, at the National Academy of Design in 1834, the reviewer for the American Monthly Magazine could only comment: “We were, in truth, somewhat puzzled at the name of this picture, and confess ourselves to be much more puzzled, now that we have seen it . . it is merely, and gratuitously, fantastical.”3 In 1886, the second owner of the painting, John M. Falconer of Brooklyn, New York, published a pamphlet claiming that “this drinking vessel of the Titans . . is in fact, a subtle reproduction of the world-tree of Scandinavian mythology.” 4 A tie to the Titans of Greek mythology is, of course, implicit in the title.

But despite all the theories seeking some symbolic meaning for the goblet, perhaps the most sensible is Ellwood C. Parry III’s, who suggests that “it is possible that a basic visual analogy was at work in Cole’s thoughts, an analogy between actual landscapes he had observed and the shape of the water vessels and basins he imagined.”5 Parry reminds us that in 1832, shortly before painting The Titan’s Goblet , Cole had been traveling in Italy and had sketched the small, circular volcanic lakes of Nemi and Albano south of Rome, emphasizing “their circular form, the steep sides covered with trees and shrubs, and the absence of a natural outlet for the waters.”6 But these were by no means the only basin lakes with which Cole was acquainted. Even more familiar were the lakes near his home in Catskill, New York, where he took up residence in 1827, chief among them the North and South Lakes near one of the young country’s first tourist destinations, Mountain House, on the Catskill Mountain plateau just to the west of Catskill itself. Cole often painted the place, as in his View of the Two Lakes and Mountain House, Catskill Mountains, Morning (fig. 3), all painted in 1844, the same year that Preuss was drawing his map of the Great Basin. I am not trying to suggest that Preuss knew of Cole’s Goblet , but I do want to suggest that they were working from the same mind-set.7 They were equally awestruck by the scale of the American landscape. Cole’s lakes were drained by Kaaterskill Falls, but they lay in a basin not unlike the one he painted in the background of The Titan’s Goblet and the one described by Frémont upon first seeing the Great Basin from the escarpment above Summer Lake, Oregon, on December 16, 1843: “Broadly marked by the boundary of the mountain wall, and immediately below us, were the first waters of that Great Interior Basin.” “In America,” he meditates later in the text,

3 “Miscellaneous Notices of the Fine Arts, Literature, Science, the Drama, & c.,” American Monthly Magazine 3 (May 1834), p. 210.

4 Quoted in Ellwood C. Parry III, “Thomas Cole’s The Titan’s Goblet : A Reinterpretation,” Metropolitan Museum Journal 4 (1971), p. 126.

5 Ibid., p. 135.

6 Ibid.

7 It is, however, possible that Preuss knew of Cole’s painting. Born George Karl Ludwig Preuss in Prussia in 1803, Preuss arrived in America in March 1834, just a month before The Titan’s Goblet was first exhibited at the National Academy of Design, and he was employed as a mapmaker for the Coastal Survey, working out of New York (his 1837 maps of Long Island’s north shore are available online at http://alabamamaps.ua.edu/historicalmaps/Coastal Survey Maps/new york - north side of long island.htm). The painting was exhibited a second time in 1838, when it was included in the Dunlap Memorial Exhibition at the Stuyvesant Institute in New York.

8 Frémont 1970 (see note 1), pp. 592, 703.

9 Clarence E Dutton, “The Panorama from Point Sublime,” in Tertiary History of the Grand Cañon District , with atlas. Vol. 2 of Monographs of the U. S. Geological Survey (Washington, D. C.: Government Printing O ce, 1882), pp. 155–56.

“such things are new and strange, unknown and unsuspected, and discredited when related. But I flatter myself that what is discovered, though not enough to satisfy curiosity, is su cient to excite it.”8 In fact, it might be that all Cole was attempting to suggest in his “fantastical” painting is this same excitement, his understanding that the American landscape is itself, like the goblet, the very work of the Gods—as vast, as awe-inspiring, as di cult to comprehend in its entirety as his imagined drinking cup. The goblet and the Great Basin might best be thought of as simple figures for the sublime.

The symbolic language of the sublime dominates American landscape imagery usually associated with altitude—with peaks, pinnacles, spires, buttes, promontories, and the views from such lofty vantage points, such as the panoramic vista of the Grand Canyon o ered up from Point Sublime (so named by geologist Clarence E Dutton in his 1882 Tertiary History of the Grand Cañon District , compiled for the U.S. Geological Survey).9 But there is a second language, more domestic—and thus not so obviously sublime—but equally pervasive: the language of containers and vocabulary of ceramics. Basin is one of these words, and not just the Great Basin, but others across the American West, like the Columbia Basin and the Great Divide Basin in Wyoming. A somewhat small version of a basin is a bowl (the back bowls at Vail and the Sugar Bowl rock formation in Green River, Wyoming), and, of course, the edge of both a basin and bowl is a rim (the Mogollon Rim in northern Arizona and Rim Rock Drive in Colorado National Monument). There are more specialized kinds of containers like cauldron (the Devil’s Cauldron in Oregon, and the related term, caldera) and pot (Teapot Dome, also in Green River, Wyoming, and the mud pots and paint pots of Yellowstone). And, finally, there is a certain vocabulary taken directly from ceramics: slab (Satan’s Slab, one of the Flatirons above Boulder, Colorado, and, in ceramics, slab construction), hollow (as in both Sleepy Hollow and, in ceramics, hollowware), plate (as in the plate tectonics that inform the elasticity of the earth’s crust), and, of course, crater (from the Greek krater , a mixing bowl).

3 Thomas Cole (American, 1801–1848). A View of the Two Lakes and Mountain House, Catskill Mountains, Morning , 1844. Oil on canvas, 35 13⁄16 × 53 ⅞ inches. Brooklyn Museum, Dick S Ramsay Fund, 52.16.

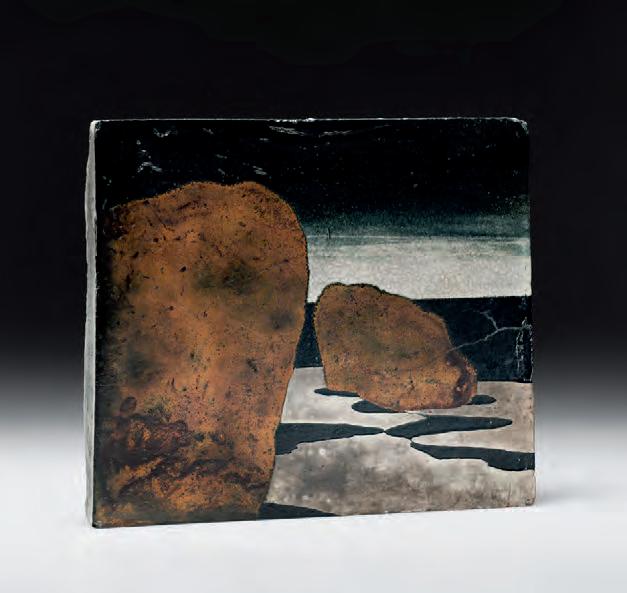

37 E VE N TIDE B EACH , 1990. Glazed earthenware, raku-fired. 14 × 15 ¾ × 2 ¼ inches. Collection of the artist

38 G REE N R IVER G ORGE , 2002. Glazed earthenware, raku-fired. 9 × 9 ½ × 3 ½ inches. Private collection

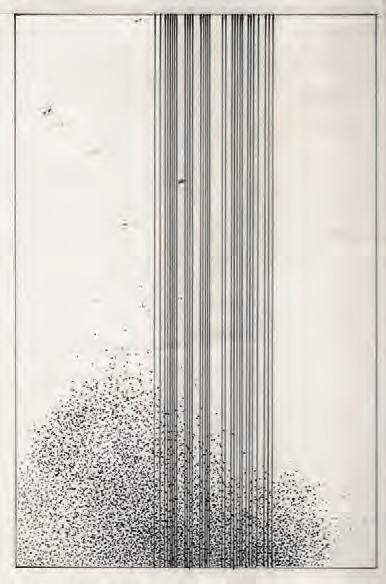

Preliminary drawing for SKYWELL FALL S , 2008. Ink on paper. 13 × 9 ½ inches. Collection of the artist

50 SKYWELL FALL S , 2009 (view from below)