ORO Editions

ORO Editions

History tells our story. Science explores how things work. Philosophy interrogates our beliefs. Art is the only human discipline that has the power to ask who we might become and how we might be better. When we see art as a creative search for public good, it ceases to be a personal aesthetic conceit and has the power to enhance cultural and environmental quality.

The art of the work for us has always been the search for public value in witness. The work of an artist who speculates on their world can be celebratory, critical, educational, therapeutic, or a combination of some or all of these. In the search for public good in architecture, we listen and research, wonder how things work, and ponder our beliefs through the design process. It is perhaps more important than ever to see architecture not as an aesthetic or formal endeavor alone, but as the art of critical and productive work, challenging and offering an alternative to the automatic economic, functional, or stylistic typologies that perpetuate outworn, unjust, and unhealthy traditions.

The design of the Cooperwood Senior Living complex was, from the start, an artistic search for a more engaging and lively home for the elderly. We pursued a critical re-making of the institutional typology by prioritizing natural light, air, proportion, color, shape, and pattern along with function. The design attempts to bring dignity to this new and expanding living typology. The design accepts that there are two scales to embrace and integrate—the intimate scale of each resident’s home and the community scale of the common spaces. Experience with aging parents implored developing the simple livability of the units as well as reconsidering the traditional four-square room where residents, depending upon their health, may spend many hours of the day and night. The simple addition of splayed exterior walls, larger-than-normal windows, and sunshades animate the interior with slightly different and expansive views of the landscape and bring ever-changing colors of natural light deep into the spaces without glare. The form and siting of the building with its faceted pattern of exterior walls at play in the sunlight build a dynamic concurrence among several contingent formal strategies. The complex feels alive with both a familiar and unfamiliar presence which we consider an example of uncanny form.

Within four months of opening, the complex was nearly fully occupied. Residents and staff members, citing the quality of the design, spaces, and environment, came from other assisted living projects to live and work at Cooperwood.

ORO Editions

ORO Editions

CARVED VALUE

Create therapeutic figures/spaces that appeal to pre-verbal qualities of experience. Develop formal strategies, ideas, materials, systems, and products to form figures of integrity that open inquiry. Overcome the fragmentary, additive reality of design and construction. Avoid modeled assembly and additive work (forms, products, and ideas) that are easily co-opted by language.

In The Image in Form, Adrian Stokes describes a model of form that was grounded in formative experience which presented a kind of otherness or independent integrity.3 He described this work as exhibiting a psycho-spatial exposure position formed with smooth internal transitions, embodied internal energy, and formal cohesion. These works exhibited carved value which can be both a provocation and an invitation in form that challenges witness. For Stokes, encounters with a work that exhibits carved value can open inquiry and the possibility of therapeutic growth. By contrast, a modeled work is characterized as a fragmented collection of parts with internal differentiation, exposed connections, and sometimes, an arbitrary ordering device to hold a composition together. Witness of modeled form can be enveloping; the spectator becomes a fragment among fragments in a possibly pleasurable but unproductive assemblage in experience.

Stokes recognized that we live in a fragmented world and often manage experience additively. However, he challenged artists to seek form that could achieve carved value, even with additive means of construction. In our search for examples in art, we have found carved value in works of art created through additive means. In sculptures by David Smith, the assemblage of parts is held together by a cohesion of common energy. In Kurt Schwitters’s collages, the phenomenally transparent positioning of disparate components binds parts into an open ensemble. In Cezanne’s paintings, the perspectival adjustments of distributed figures form a tension in witness, and a textural applied color palette bridges differences to make both a scene and a surface hold together.

Experiments to achieve carved form in the work can be found in the composite shape transformations in the Mississippi Library Commission, the overlapped interior spaces experienced as pause and move plans in multiple projects, and the distributed figures between sister components in the Clarksdale Coahoma Higher Education Center and the Springdale Municipal Complex.

ORO Editions

ORO Editions

ORO Editions

ORO Editions

ORO Editions

ORO Editions

MACHINE

Do not borrow money. Work to achieve high-quality buildings within the funds available. Plan carefully and be efficient. Raise fees. Keep the overhead low. Pay staff at the highest rate possible. Maintain a studio that can choose the next project. Do not create a machine that needs to be fed.

Most of the expense for a studio is dedicated to team salaries. This is the greatest investment a firm can make to advance the quality of the work. We pay each team member as high a salary as their education and skill demands and as we can afford. We do operate as a meritocracy and support initiative and skill development with opportunities, salary increases, and bonuses. The remaining overhead expenses are small but we strive to keep them low. This business strategy of investing in the team and keeping all other costs minimal has served us well over the years. The cash flow of an architecture firm is an almost impossible management problem. There are many outside variables that are out of our control. Projects can start, stop, or be canceled. Clients can be slow in paying for services. New projects can walk in the door while you are otherwise committed and tempt you to grow to meet the challenge. We joke, we always seem either six months from bankruptcy or pressured and behind with more work than we can do.

During most of the firm’s life, we operated debt-free. There were, however, two periods of time when we broke this foundation, for good reason, but the price was high. The first was after the 2008 fiscal crisis. This downturn hit the health of the firm in 2011. Slowly, over the year, we completed long-term projects and had very little new work to start. In the last quarter of 2011, work was scarce, and we had used our reserves. At the end of the year, we borrowed a good bit of money to make payroll and provide bonuses to the team who had worked hard all year. We knew every business-minded person would tell us that without signed contracts for future work, this decision was crazy, but we kept the team together.

As luck and hard work combined over the course of the following year, we received 26 new commissions. We did not miss a beat and moved on to the new year and work. While borrowing money turned out to be the right thing for the work and firm, it did hurt. It took two years to pay back the loan. Every month over those two following years, the debt payment added to our overhead and stole a little design time.

The second time we borrowed money was after the pandemic. Even with the federal aid in the form of a PPP loan, work slowed and cash flow was challenged. Over the course of 2021 and 2022, we slowly borrowed more cash to make payroll and pay bills, and again, paying it back is painful. Today, with hindsight, we might change this foundation to strive to avoid debt and balance short-term needs with the long-term goals of the firm. Today, we have set new goals for greater reserve funds as we work to pay back the loans we took to recover from the pandemic.

ORO Editions

ORO Editions

SUCCESS

Measure success by our client's satisfaction and joy, not by awards programs.

We are fortunate to serve a diverse group of clients and to complete multiple projects for some of them over many years. Most of our clients are public agencies or clients who provide public services. They include the General Services Administration, the National Parks Service, the Mississippi Department of Transportation, the Jackson Housing Authority, the Mississippi Military Department, private and public schools (K-12 and higher education institutions), non-profit organizations, municipalities, individuals, and affordable housing developers. In each case, we seek to understand, support, and amplify their public missions for public value.

It is a joy to visit Operation Shoestring to witness the children in the afterschool program. It is a delight to learn that a Methodist pastor chooses to write his sermons in the Mississippi Library Commission or to witness the residents of the Baddour Transitional Homes proudly offer tours to visitors. It is also important to measure benefits beyond the lot lines of the project into the community. In the Midtown neighborhood in Jackson, the community planning work we completed in 2011 provided a strategic road map for the revival of this blighted and troubled neighborhood. The plan identified development interventions that were designed to ignite private investment. The planning work included leadership training for committed residents and helped form many partnerships, including the local college business school. Since the planning work, multiple new affordable housing projects have been completed, new businesses have been started, crime is down, and for the first time in years, Midtown is attracting new homeowners who are able to secure home financing from local banks. These are stories of success.

We have learned the value of submitting projects for awards. Each entry offers an opportunity to document the project and reflect on its strengths and weaknesses. If the project wins an award, we certainly celebrate with our clients and our team. If it does not win, we remind ourselves of this foundation.

ORO Editions

The practice of architecture is servant leadership, which for us, has come to mean a teacher: a teacher leading the design team, a teacher in the work, and a teacher during construction.

Cities, landscapes, and buildings are also teachers. They frame our interaction. They articulate our values. They can facilitate or inhibit social life. We learn what is private, public, shared, and negotiable. Our work as architects is to make physical forms and spaces that promote the best of human possibilities.

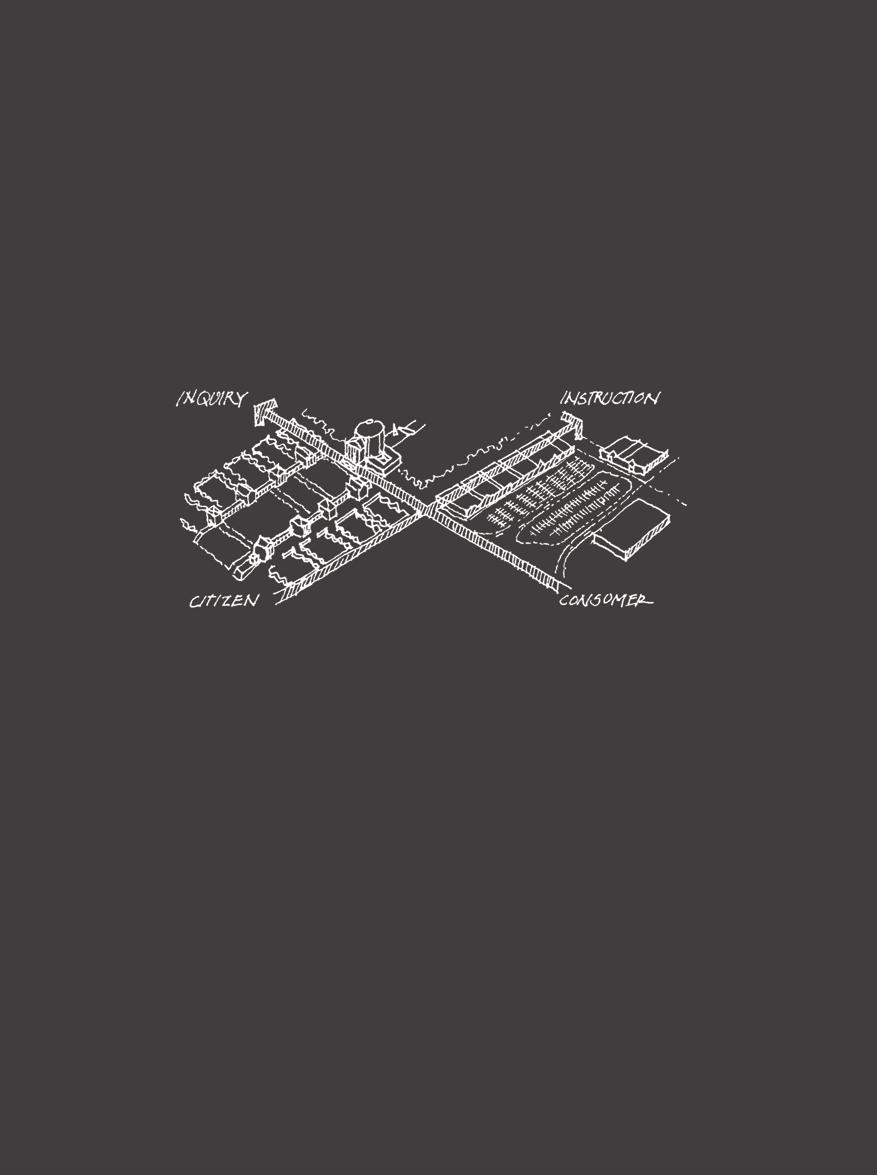

We believe in cultural growth. Growth, however, is not possible without criticism, resistance, and proposals that promote active inquiry. We witness how authoritative structures of consumerism can rob us of engaged spatial experience. We work to make forms and space that awaken the slumbering subject. We work to create projects that are scaffolds for inquiry. We strive for mixed-use, diverse, spatial circumstances in character-filled environments. We see this work as therapeutic.

In our region of unskilled labor, we try to support the growth of construction skill and handwork. Today’s contractors are managers who hire marginally skilled subcontractors to complete the actual work. We have no unions, few trade schools, and even fewer apprenticeship programs. In traditional contracts, means and methods are separated from the architect’s responsibility. Because the contractor is at risk for performance, they are solely charged with the means and methods of construction, but they often have only rudimentary knowledge and skills. The quality of building construction often suffers. We have developed a scope of construction work that includes training, performance standards, and practice mock-ups designed to develop skill and an ethic of craft on all projects. While an architect’s knowledge is second-hand, together with a contractor, we can develop a level of craftsmanship that is superior to the status quo. Over twenty years, we have seen this approach bear fruit. Contractors in the area have developed exceptional skill in architectural concrete work, masonry, and metalwork and have carried these skills and this ethic on to future jobs.

ORO Editions

ORO Editions

ORO Editions

ORO Editions

ORO Editions

ORO Editions

ORO Editions

Publishers of Architecture, Art, and Design

Gordon Goff: Publisher

www.oroeditions.com

info@oroeditions.com

Published by ORO Editions

Copyright © Duvall Decker

Architects 2023

Text and Images © Duvall Decker Architects 2023

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including electronic, mechanical, photocopying of microfilming, recording, or otherwise (except that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the publisher.

You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Graphic Design: Katherine Flannigan

Text: Anne Marie Duvall Decker, FAIA; Roy Decker, FAIA

ORO Managing Editor: Kirby Anderson

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 First Edition

Library of Congress data available upon request. World Rights: Available

ISBN: 978-1-957183-51-0

Color Separations and Printing: ORO Editions, Inc.

Printed in China.

International Distribution: www.oroeditions.com/distribution

ORO Editions makes a continuous effort to minimize the overall carbon footprint of its publications. As part of this goal, ORO Editions, in association with Global ReLeaf, arranges to plant trees to replace those used in the manufacturing of the paper produced for its books. Global ReLeaf is an international campaign run by American Forests, one of the world’s oldest nonprofit conservation organizations. Global ReLeaf is American Forests’ education and action program that helps individuals, organizations, agencies, and corporations improve the local and global environment by planting and caring for trees.