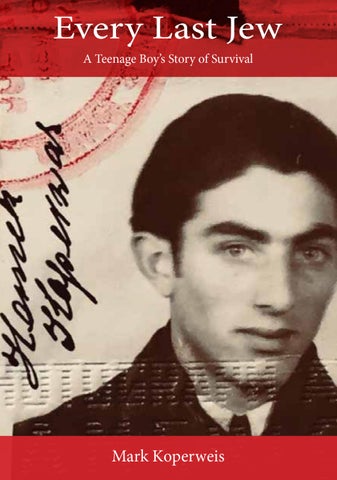

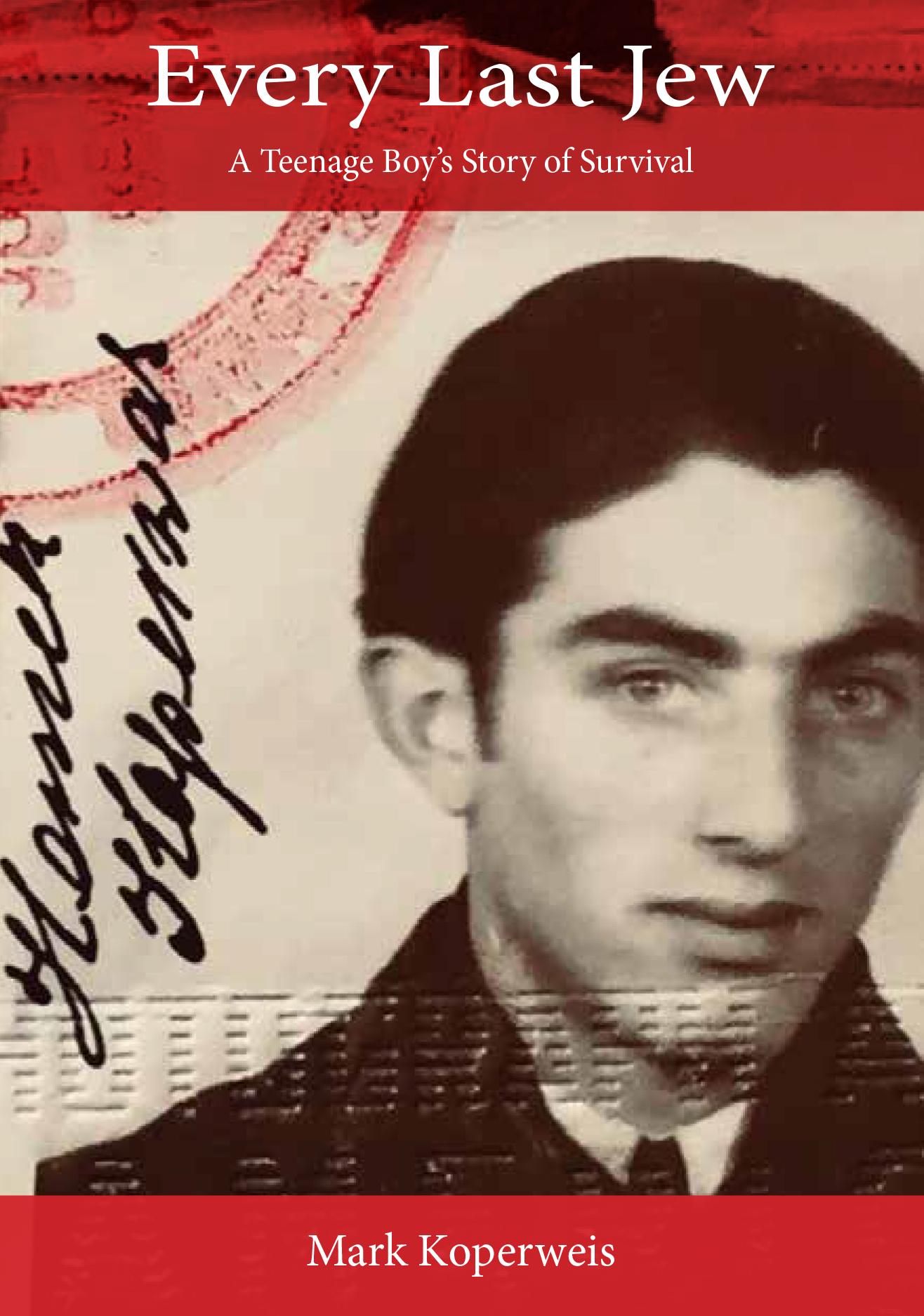

Every Last Jew

Preface

We often hear the imperative “Never Forget.” Growing up with a father who survived the Holocaust, forgetting was never an option for me, not even for a moment. Some Holocaust survivors put their experience behind them and never mention it again because they don’t want their children to have to relive what they went through. They want to insulate their children from that horrible part of their life. Not my father. Ever since I can remember, my father has been telling stories of his survival. This has created a constant background narrative in my life that I carry with me always.

When life throws its challenges at me, when bad things happen to me, when things become extremely difficult, when I am at my lowest point, my father’s narrative starts playing in my head, reassuring me that whatever I am going through at the moment pales in comparison to what he went through. He never gave up; how can I? He persevered; I must. If he never lost hope, then I surely cannot. This attitude is in no way intended to trivialize the suffering of others, no matter how small physically or mentally. Everyone has their own struggles, and they are real. The point is that if you are suffering, you need strength, determination, and hope to move

through the pain and come out of the other end of the tunnel of despair. My father’s story provides that for me.

My entire life I have always been driven to document my father’s experiences so that future generations of our family would know what he and his family went through. About twenty years ago I decided to record my father. I collected over six hours of video and audio recordings of him telling his story along with my asking him questions. It is from those recordings that I have compiled this book.

People often ask me why I feel the need to tell this story. They say that there are already so many stories published about the Holocaust, so why do we need yet another? My response is, “Six million Jews were killed. Every one of them had a story to tell. When there are six million stories published, you might have a point. It is only through the stories of those that survived that we can know the stories of those that did not.”

The purpose of remembering is not to carry a life-long grudge, or to seek revenge, or to label a group of people as evil; that is what the Nazis did. A basic belief of the National Socialists was that Jews were an inferior race. They condemned an entire group of people based on nationality and ethnicity. The purpose of remembering what happened to the Jews of Europe is to learn from the past so that as a society we do not repeat our mistakes. It is for this reason that I am compelled to tell my father’s particular story of survival.

Chapter 1

Kilinskiego 11

Henry shared a single bed with his two younger brothers, Avram and Chaim, in a three-bedroom flat in a run-down brick building in Radom, Poland. His Polish name was Hennek, but his family called him by his Yiddish name, Haskel. His three older brothers, Harry (Herschel), Julius, and Joe (Yasel), along with their sister Celina, shared another bedroom; and his mother and father were in the third. His oldest sister Sala was already married and living with her husband Moishe a short distance away. Henry woke up early one day so that he and his brother Harry could get fresh milk from the market. He washed his face in a basin in the foyer next to his room and then put on his clothes, making sure not to forget his white armband with a blue Star of David in the center. His father, Zygmund, was at his sewing machine in their living room, which doubled as a tailor shop. His mother Ida was busy preparing breakfast. There was a small container of milk sitting on the window sill. It had been there for a few days curdling into buttermilk. Together, Henry and his older brother Harry carried a large five-gallon aluminum container as they walked to the marketplace. They passed businesses and shops

that had paper signs posted on them letting the public know that they were owned by Jews. As they made their way to the market they were careful not to walk on the sidewalk, as it was forbidden for a Jew to do so. Instead, they walked in the street alongside the curb paying particular attention so as not to be struck by a vehicle. After they got the milk, it took all of their strength and dexterity to carry it back without spilling any. There was a small storage area in the basement of the apartment that was allotted to their family to store their groceries to keep them fresh, but there was no refrigerator. They struggled down the few steps to the cellar and placed the container in its usual spot. Herschel grabbed a ladle that was hanging on a hook, opened the lid of the container, scooped out some milk, and carefully filled a bowl to bring upstairs.

When they came upstairs their mother Ida had breakfast prepared: hot cereal and fresh bread. There was no juice, as that was a luxury. The only time they had juice was when one of them was sick. It served as medicine. Ida began serving the cereal as the whole family sat at the breakfast table together. It had been several months since the Germans announced that all Jews were forbidden to go to public school. They even closed all Hebrew schools. Before this happened, Henry would typically pack his small tin with lunch after eating breakfast, and accompanied by his siblings he would walk

Chapter 3

Every Last Jew

Henry slowly opened the holster holding the Luger as his heart pounded. He anxiously looked back at the door of the barracks to see if the Obersturmbannfuhrer (Lieutenant Colonel) was approaching. The gun felt cold and heavy in his hand. Henry was familiar with the sight and sound of this particular weapon although he never held one in his hands. He had heard it fired and had seen the damage it was capable of. This particular gun belonged to Obersturmbannfuhrer Baumann. Henry was assigned the tasks of shining Baumann’s boots and leather holster, mending his uniforms, straightening his quarters, and even cleaning his gun—the gun he was now holding for the first time, which was beckoning him to take action.

His mind started racing with ideas of waiting for Baumann to walk through the door and shooting him in the face. “I should kill that bastard,” he thought to himself. “He won’t know what hit him. I’ll show him who’s in charge. Then I’ll run outside and kill as many rotten, goddam Nazis as I can before the guards in the towers shoot me dead. Everyone will watch with awe and disbelief. I’ll die a hero, on my terms, and not at the

whim of a Nazi who takes pleasure in killing Jews. That son of a bitch, Baumann—I’ll show him!”

Just then the door flung open. Henry was startled. He quickly turned his head toward the door. It was Baumann, who stopped for a brief moment and was also slightly startled to see someone in his quarters. Henry’s heart was racing as a flash of blood filled his head with a warm wave of fear. Baumann appeared to Henry as a towering figure slightly silhouetted by the daylight behind him. He was wearing his full green-gray uniform, replete with epaulettes, medallions, and badges, including the allpervasive haunting swastika. His tall black, well-polished boots and officer’s cap added to his intimidating air of authority. Henry was momentarily paralyzed in fear.

Seeing Henry, a boy barely 15 years old, standing motionless, holding his sidearm, Baumann smiled. Henry was both relieved and confused. “Be careful, that’s loaded, my boy; you could hurt yourself,” Baumann said jokingly. Henry turned and placed the gun back in its holster, breathing a silent sigh of relief. “I should’ve shot the bastard,” he thought, feeling somewhat disappointed in himself. “But then what? What would I have gained? Do I really want to die? I want to find out what happened to the rest of my family. Are they still alive? Are they in a camp similar to this one? If they had this chance, would they have the audacity to shoot a Nazi officer? Or would

Chapter 3

Every Last Jew

Henry slowly opened the holster holding the Luger as his heart pounded. He anxiously looked back at the door of the barracks to see if the Obersturmbannfuhrer (Lieutenant Colonel) was approaching. The gun felt cold and heavy in his hand. Henry was familiar with the sight and sound of this particular weapon although he never held one in his hands. He had heard it fired and had seen the damage it was capable of. This particular gun belonged to Obersturmbannfuhrer Baumann. Henry was assigned the tasks of shining Baumann’s boots and leather holster, mending his uniforms, straightening his quarters, and even cleaning his gun—the gun he was now holding for the first time, which was beckoning him to take action.

His mind started racing with ideas of waiting for Baumann to walk through the door and shooting him in the face. “I should kill that bastard,” he thought to himself. “He won’t know what hit him. I’ll show him who’s in charge. Then I’ll run outside and kill as many rotten, goddam Nazis as I can before the guards in the towers shoot me dead. Everyone will watch with awe and disbelief. I’ll die a hero, on my terms, and not at the

whim of a Nazi who takes pleasure in killing Jews. That son of a bitch, Baumann—I’ll show him!”

Just then the door flung open. Henry was startled. He quickly turned his head toward the door. It was Baumann, who stopped for a brief moment and was also slightly startled to see someone in his quarters. Henry’s heart was racing as a flash of blood filled his head with a warm wave of fear. Baumann appeared to Henry as a towering figure slightly silhouetted by the daylight behind him. He was wearing his full green-gray uniform, replete with epaulettes, medallions, and badges, including the allpervasive haunting swastika. His tall black, well-polished boots and officer’s cap added to his intimidating air of authority. Henry was momentarily paralyzed in fear.

Seeing Henry, a boy barely 15 years old, standing motionless, holding his sidearm, Baumann smiled. Henry was both relieved and confused. “Be careful, that’s loaded, my boy; you could hurt yourself,” Baumann said jokingly. Henry turned and placed the gun back in its holster, breathing a silent sigh of relief. “I should’ve shot the bastard,” he thought, feeling somewhat disappointed in himself. “But then what? What would I have gained? Do I really want to die? I want to find out what happened to the rest of my family. Are they still alive? Are they in a camp similar to this one? If they had this chance, would they have the audacity to shoot a Nazi officer? Or would

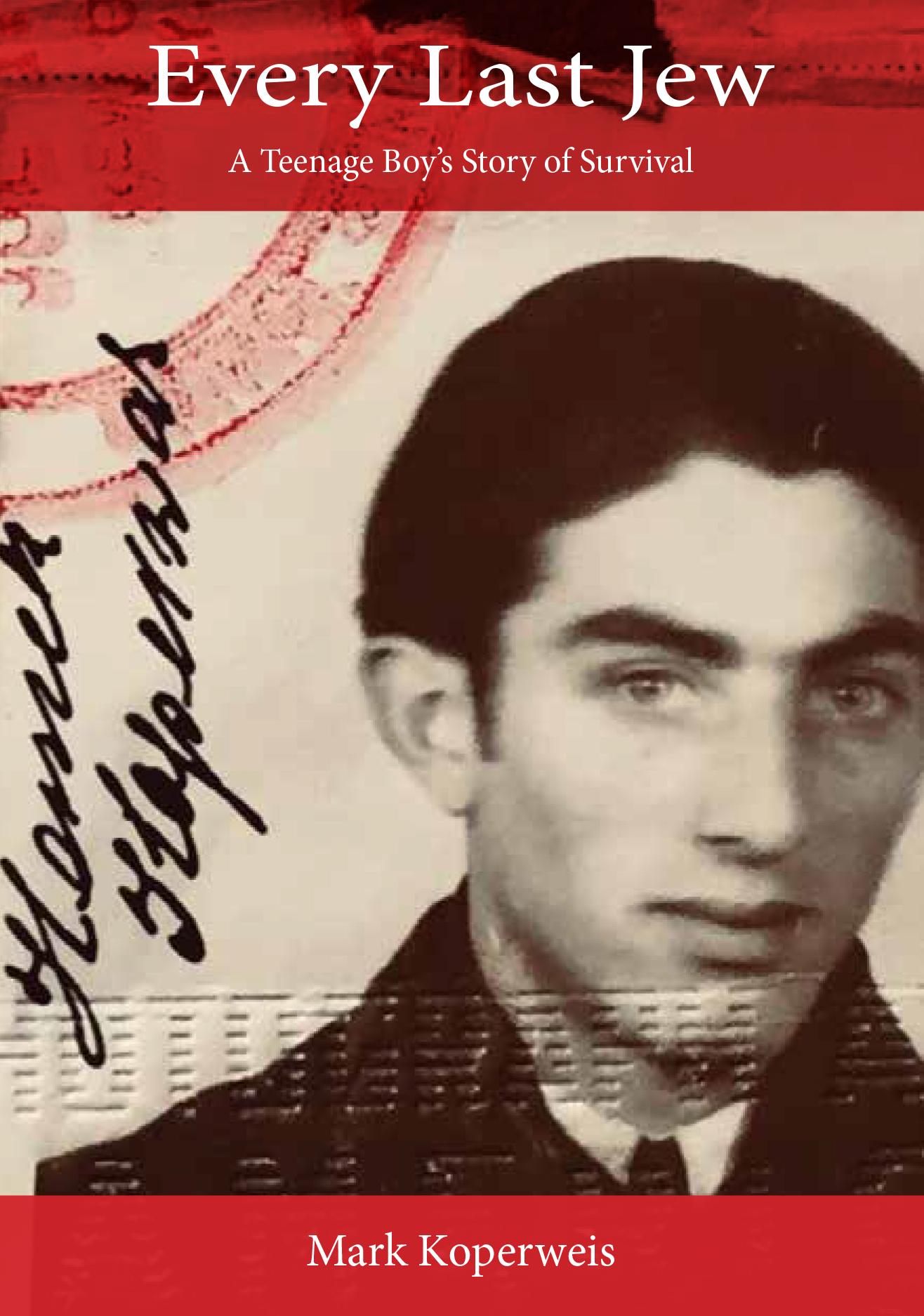

Henry’s mother Ida, circa 1939. Only existing photo.

Henry’s father Zygmund, circa 1939. Only existing photo.

Henry’s oldest sister

with her husband Moishe, circa 1939. One of two existing photos.

Only existing

Sala

Henry’s older sister Celina, circa 1939.

photo.

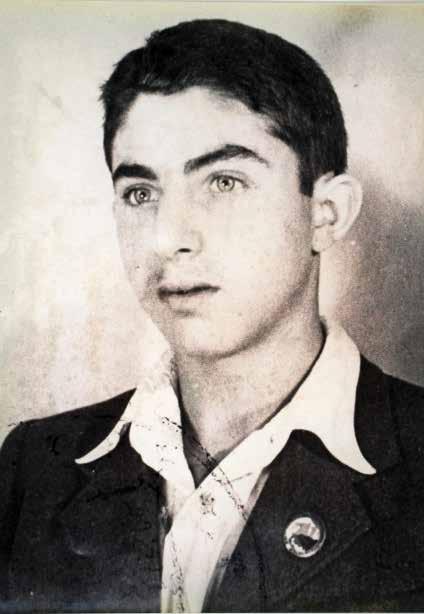

Henry shortly after liberation. 1945.

Chapter 6 Eating With Swine

When you’re hungry all the time there’s not much else you think about. Family members, friends, the past and future, are all subordinated to the task at hand: satisfying that inexorable gnawing hunger that consumes your attention. For Henry, it began as soon as he woke up till the time he went to sleep. It had been over two years since he was separated from his family members, yet he didn’t cry anymore. In fact, he almost never thought about them, at least not consciously. Instead, his waking moments were filled with nothing but thoughts of survival: how to get enough food to stay alive. A bowl of watery soup once a day was not enough to sustain a human being. Henry had to steal food from the German soldiers or from the potato fields nearby. Fortunately he knew someone who was giving out the daily rations of soup and was making sure his scoop came from the bottom of the pot where some of the vegetables were lying. That helped a great deal but it wasn’t enough. If he was lucky he could make it one more day. But for what? When you were exhausted and of no more use to the Nazis, they would dispose of you like a broken part in a machine. Still, deep in his subconscious Henry had

hope: an irrational belief that somehow things would be different tomorrow. Somehow—God knows how, but somehow—things would be better. After all, just a few years ago things were drastically different for him when he was living with his family in Radom. Compared to his situation at present, life then was great, even though they were living in squalor in the ghetto. Now, just a few years later, everything was different. Deep down inside himself, he believed that things could change quickly again for the better. As hard as it was to believe, he felt that the Germans could be stopped and he would be set free—free to find his family and to live his life as he chose. Remarkably, hope was still alive in him.

When he arrived at the labor camp in Vaihingen he was given a new uniform. He took off his old lice-ridden one that he had been wearing for almost two years. He knew that the new uniform was most likely worn by someone else who had died in it, but he didn’t care. It was clean. He was allowed to work with his older cousin Leon in his tailor shop. The Germans needed a small group of tailors to mend their uniforms. Henry was one of ten people who had the privilege of working indoors, escaping the brutal cold of the outside. He knew nothing about tailoring when he started working there, but under Leon’s tutelage he caught on quickly. Another older cousin of his, Saul, worked as a cobbler and was able to get him a decent pair of German army shoes as well. To

Chapter 8

Born Again

For the first time since he could remember, Henry was happy and hopeful. When he first arrived at Dachau he immediately noticed how easy the prisoners had it. “These people look like they get enough food to actually stay alive,” he pleasantly thought to himself. “Maybe those rumors about being traded for German prisoners are true after all.” The conditions Henry was used to were a thousand times worse than what he now saw. He was led to his barrack along with several dozen other Jewish prisoners wearing striped uniforms. They walked down a narrow road with long single-story buildings on either side. He saw Americans, Canadians, Russians, and Frenchmen all busy hanging their clothes out to dry, cleaning, working on small tasks, and most surprisingly, lounging about. “There’s no forced labor?” he wondered to himself. “Wow, this is like a convalescent home.”

A German officer brought Henry and his group to a building where they were instructed to take off their clothes and shower. They were given fresh uniforms. “You are now political prisoners of the German Army,” he announced. “The Red Cross is here doing an inspection. You will not talk to them. If you are heard speaking with

them you will be dealt with harshly. “Verstehen?” (“Do you understand?”) The officer then left the building. Henry understood. He would not be telling the Red Cross how he just came from the salt mines in Kochendorf and witnessed hundreds of men expire from exhaustion and malnutrition. He would be silent about how he had to steal food from the knapsacks of German soldiers when their backs were turned, risking his life so that he wouldn’t starve to death while he did back-breaking slave labor for twelve hours a day. He would not say a word about the long march to Dachau, with nothing to eat for days, and how he watched men drop dead by the dozens as he walked beside them. He would say nothing about how he reached down to pick up a rotten apple core he saw lying on the road, only to be stabbed in the back by a bayonet on the end of German officer’s rifle. No, he was not going to ruin his chances of being traded for German soldiers and gaining his freedom. There would be plenty of time to speak later if he was lucky enough to live until then.

Henry couldn’t believe that he had his own cot to sleep on and that he didn’t have to share it with three or four other men. As the men began settling into their new surroundings they began talking about rumors they each heard of what was going to happen to them.

“The Germans are short of supplies and trucks,” one man voiced aloud. “That is why they are trading us.”

Chapter 10

The Journey Home

As Henry sat in his barrack looking out into the displaced persons (DP) camp that he was temporarily being held at, he had only one thought in his mind— “Who from my family has survived?” At this point in time he had no idea that more than three million of his fellow Jews from Poland were murdered. The Jewish population of Poland before the war was roughly 3.5 million. Less than ten percent survived the Nazi genocide. What he did know, and found hard to believe, was that he was alive, and free. Now it was up to him to decide what to do with the rest of his life. He would decide where to live and what kind of work he would do to make a living. He had just turned 19 years old on the very same day that he was liberated by American GI’s. He was reborn from the womb of hell into the arms of freedom, and his first order of business was to find the remaining members of his family.

The United Nations Refugee Relief Agency, otherwise known as UNRRA, set up an office at the center of the DP camp. They gave Henry a temporary passport that allowed him free travel to anywhere within Europe. After a couple of months of recuperating and telling his story

to the UNRRA workers and American GI’s, Henry set out for his hometown of Radom, Poland. He was told that if anyone from his family had survived, they would most likely go there first. On his way to Poland, Henry stopped in Prague, Czechoslovakia. He travelled by bus and train and was carrying all of his life’s possessions in a small, badly worn leather suitcase.

It had only been a short time since the fighting ended in Prague. The devastation was palpably visible. Bombed-out buildings, abandoned military vehicles, and debris were everywhere. When Henry came into town he stopped in front of a large makeshift chalkboard. On it were dozens of names handwritten by survivors. Next to the names were addresses letting separated family members know where they were staying. He started reading down the list, hoping to find a familiar name. To his utter astonishment the name Herschel Koperwas appeared on the board. “Oh my God,” he exclaimed, “that’s my brother!” He was overwhelmed with joy and excitement. Next to his brother’s name was an address of where he was staying in Prague.

Henry quickly made his way through town to the address of his brother. Filled with anticipation he remembered the last time he saw Harry. It was in Tomaszow just outside Radom over three years ago. They were both building barracks there for German soldiers. He and Harry along with their family were forced to live

About the Author

Mark Koperweis is co-founder and Executive Director of the Henry Koperweis Foundation for Holocaust Education, a non-profit organization dedicated to educating the public about the atrocities committed by the Nazis against the Jews of Europe.

He lives in Oakland, California, where he owns and operates a successful window coverings business— draperyGuru®.

This is his first book, compiled from hours of recorded interviews with his father Henry—the subject of this memoir.

To learn more please visit: www.henrykoperweisfoundation.org