CAMPUS ARCHITECTURE

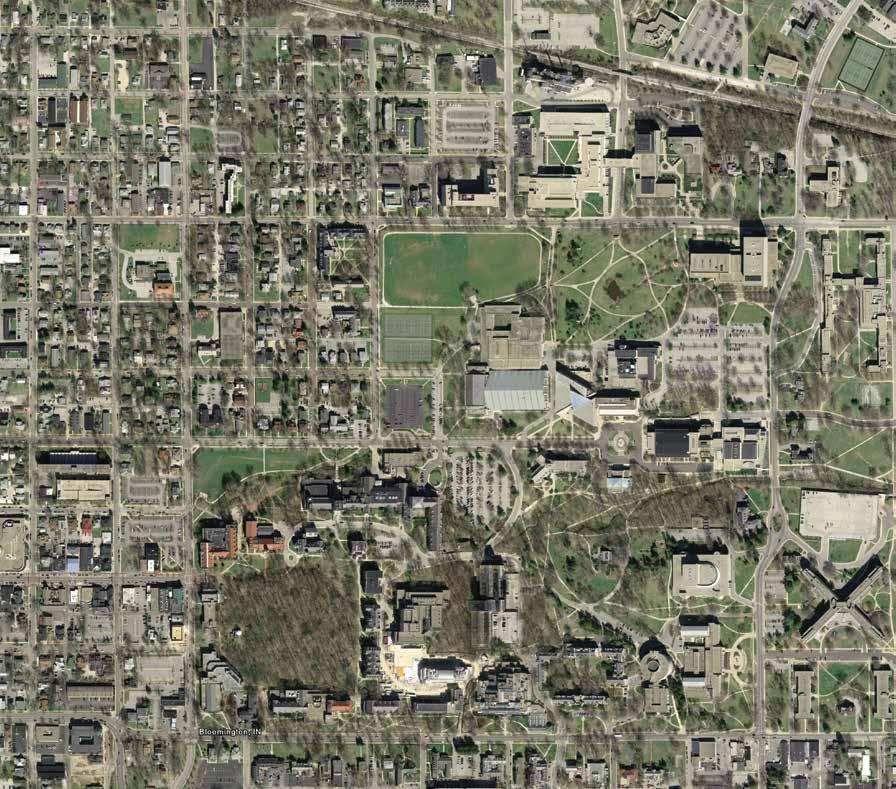

The new Global and International Studies building is located on the Bloomington campus of Indiana

The “Stone Belt” — known to geologists as the Salem Limestone Formation — includes the towns of Bedford and Bloomington. Exceptionally deep and plentiful, Salem Limestone is both extremely durable and an excellent carving material — overall, an outstanding building material. This region of south central Indiana, roughly ten miles wide and thirty-five miles long, is home to the

The architectural character of the campus reflects the region’s long history with the limestone industry, and the campus itself rests on a bed of

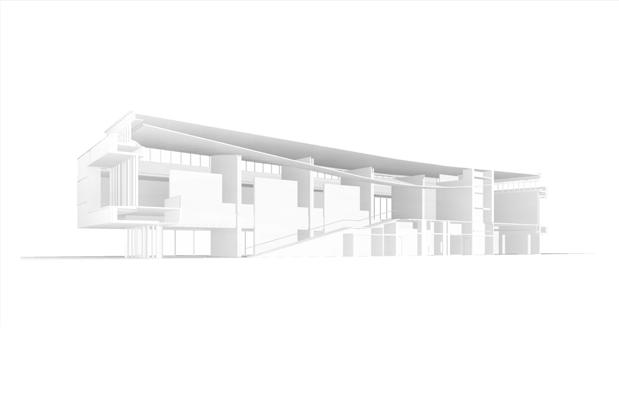

Located at the heart of campus, the gently sloping site links two distinct site conditions: the arboretum to the west and the rectilinear order of the campus to the east. The building’s integration with the topography reinforces this dialogue.

Each time I enter this building, I am struck by how light attaches itself to the stone wall in the atrium, by the sensation of floating in air when I am on the third-floor walkway.

Purnima Bose

English and International Studies Professor

International Studies and Indiana University Trustee

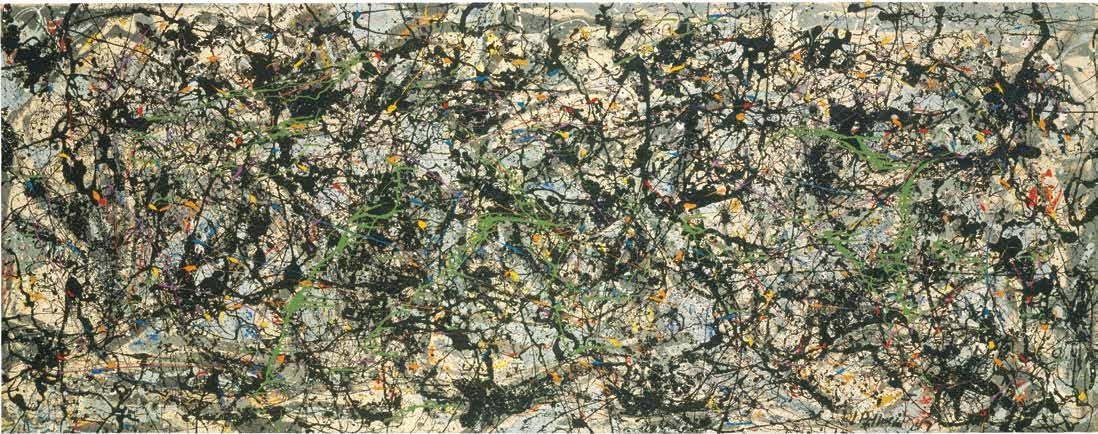

Stanford University is home to the core of the Anderson Collection, one of the world’s most outstanding private collections of 20th-century American art. The Bay Area family of

Harry W. and Mary Margaret Anderson, along with Mary Patricia Anderson Pence, built the collection over nearly 50 years before donating it to the University.

Harry W. “Hunk” and Mary Margaret “Moo” Anderson, and their daughter

Mary Patricia Anderson Pence, nicknamed “Putter,” lived day in and day out with many of the pieces that will be showcased at Stanford for years into the future.

As with many great things in life, the collection began with a meal — well, billions of meals, really. While a student at Hobart College immediately following World War II, Hunk and two of his fellow classmates, Bill Laughlin and William Scandling, became entrepreneurs when they took over the school’s cafeteria operations. The trio devised an original method of financing their endeavor by charging students for meal tickets in advance. The business grew into the mega-corporation Saga Foods.

The prosperity of Saga afforded the Andersons the opportunity to travel. In 1964, they visited Paris and discovered their raison d’etre. “Seeing the Impressionist paintings was an awakening,” recalls Moo. “We’d found our passion,” echoes Hunk. When the

pair returned home to Northern California, where Saga was based, they set their sights on collecting.

“We originally wanted to collect Impressionists,” says Hunk, “but soon realized that everyone else did, too.” So they turned their attention to early American modernists like Georgia O’Keefe. Five years later, they started to concentrate seriously on post-World War II American art — and concentrate they did. The late Stanford art history professor Albert Elsen proclaimed that the Andersons had created a “collection of collections.”

The couple devoured books and catalogs on art and attended shows and auctions. Elsen became a good friend, as did Oakland artist Nathan Oliveira, who introduced the Andersons to many of California’s vibrant artists.

A large part of the Andersons’ collecting philosophy emerges from their equal beliefs in “the head and the hands” — meaning that they look for ingenuity as well as masterful craftsmanship in the art they acquire. The Andersons focus on work that reveals the artist’s physical touch and hands-on skill. Hunk stresses, “We always ask two questions about a piece of art before we consider acquiring it: Have I seen it before? Could I have thought of it?” That clear vision has helped guide Hunk and Moo and their daughter Putter over the years.

Stefanie Lingle Beasley 2014

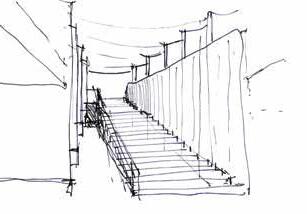

The main stair hall at the Anderson Collection has been carefully calibrated to perform a number of important functions. First, it must bring the visitor up fifteen feet to the gallery level. Therefore it has been attenuated to be as gentle and gracious as possible, a promenade architecturale that enhances the experience of accessing the gallery level. By using very low risers and longer treads than are typical, the stair provides a graceful, gradual ascent to the gallery level, so that one does not notice the substantial distance that it traverses.

But there is another, more important reason for this kind of stair. Its cadence is designed to slow one down. It invites the visitors to take their time, and gives them time to clear their heads and leave the hubbub of the outside world behind. Almost imperceptibly, the stair narrows as it rises, increasing the feeling of length and reducing its scale.

As the space slowly unfolds, and the art begins to reveal itself, the wonder of this collection becomes clear. Arriving at the top, one is literally in a different place, but hopefully mentally and emotionally as well — ready to experience art.

Once on the gallery level, the other purpose of the stair hall becomes apparent. The placement

of this large open area at the center of the plan provides a memorable space that also serves as an organizer, a constant reference point to locate yourself. It also unites the collection: views across the space from one gallery to another allow one to make connections between various pieces in the collection.

This is much the same way that the Andersons’ house works, with its rich blend of small spaces that nonetheless allow longer views from room to room, working as a multiplier. While the gallery is vastly larger than the intimate scale of the house, the new building channels that special experience and translates it into something new.

Arizona State University (ASU) and key leaders of the City of Phoenix recognized the value of moving the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law from Tempe to the Downtown Phoenix campus. While other law schools were disinvesting, ASU saw an opportunity to innovate and grow. At a moment when law education was in crisis, with great reductions in applications and with a national citizenry alienated from the value of law as fundamental to our democratic ideals, we saw an opportunity to define a new educational paradigm, and connect the legal academy directly to the urban public.

We quickly established three goals that helped keep us on track. We aimed to create a space that could help us recruit great students and faculty; better connect us with the legal community and provide students with job opportunities, scholarships, and innovative programming; and signal that we are a law school that thinks differently about the relationship between scholarship and professional practice.

Our new space had to be open and inviting to the general public; we wanted them to connect with the laws and institutions that affect our lives every day. We committed to building a law school that

would be integral to the fabric of the community and would serve as a model for legal education in the 21st century.

As part of the design discovery process, we visited law schools across the country. We sought inspiration, but found little. The buildings and their features — classrooms, décor, walkways, unused ceremonial courtrooms — all looked alike and all followed two basic design principles: to keep faculty away from students; and to keep the law school away from the public.

We chose Ennead (and Jones Studio — Ennead’s selected co-collaborator) not only because they were a firm with deep roots in higher education, but because they listened. At the earliest stage, we were all struck by how much Ennead’s conceptual design had far more to do with what we wanted to accomplish than what they thought we “needed.” Ennead knew, intuitively, that what we really wanted was a firm that designed around our ambitions. In countless ways, Ennead showed us that they cared just as much about how the building would impact our learning culture as they did about the building’s aesthetics.

Having true partners is crucial. Ennead and Jones Studio were far more than just designers — they were terrific partners in making our ideas even better. From initial designs to the ultimate facility, Ennead took our unformed ambitions and often-wild hopes about what we could accomplish and turned them into actionable ideas in the building. Now, as anyone who has gone through the process of new construction also knows, project cost and budget are always a concern. In the end, the absolute core ideas — the incredible retractable Great Hall door, the 5th floor patio, the digital engagement spaces for our community — were all able to be preserved. Indeed, we can safely say that although the hashing out and trade-offs to align cost with budget were daunting, we tackled them as a team.

At that point, it was no longer a question of “if” but “how” the building would come together, and that spirit allowed us all to deliver a facility of incredible urban impact, with inspirational spaces, and an environment that makes our approach to legal education more effective.

As we approach the end of our first year here, every wish we had for the building has been exceeded. When we worked with Ennead and Jones Studio to create the BCLS we wanted to ensure certain principles were met: a better education for our students through increased informal interaction with faculty; broader engagement for our faculty and students with the Phoenix community; better alumni engagement and interaction; and establishing the College of Law as a premier institution of legal education for law and non-law students alike.

The 5th floor patio, the Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation Courtyard, has been the center of faculty and student interaction. On any given day, one can find dozens of students and faculty having lunch, talking informally about the law and engaging the informal learning where real breakthroughs take place. It is a near magical place — bathed in sunlight and shade throughout the day and a center for the social and teaching life of the College.

The W.P. Carey/Armstrong Great Hall, with its fully functioning retractable wall, has brought nearly a hundred events — both law and non-law — to the College; that would never have happened in any other space. The beauty and grandeur of that facility deeply impresses all who enter — but it also reifies the principle that this law school is part of our community. We are embedded within the fabric of social and legal life here in our city, and this inures to the benefit of many communities.

In August 2016, we held our grand opening. More than 2,000 of our alumni attended that daylong event. Yes, there were “luminaries” in attendance — Senator John McCain, Mayor Greg Stanton, University President Michael Crow and, of course, our living inspiration in Justice Sandra Day O’Connor. But what truly made it an amazing event was how many alumni we met who had not engaged the law school in years. And there are results: the College of Law has increased alumni giving this year to the highest level in its history.

Finally, the impact of this facility, its beauty and its mission, has established the College of Law as a premier institution of higher learning. In a time when the vast majority of law schools are struggling, the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law at Arizona State University has risen to historic highs. Ranked in the top 10 of all public law schools, the College has seen applications rise more than 40% (while the nation has seen a decrease); we have admitted our strongest and largest classes; and have set all-time records for philanthropy and engagement.

There are many reasons for our success: our maverick spirit, ASU’s vision for the re-invention of higher education, and a renewed commitment to renewing the urban core of Phoenix — but now that I have had an education about making buildings of great social and pedagogical impact, I deeply value the power of design. It’s been an incredible journey. We have realized our vision for the building, which places us squarely at the intersection of law and society. We couldn’t have made this vision a reality without our extraordinary partners and friends, Ennead Architects and Jones Studio.

Douglas Sylvester Dean and Professor of Law

Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law

Unlike traditional retractable seating, where the chairs and tiered platforms are attached and both are retracted together, the design team developed a motorized “tray” system that allows for each row of auditorium chairs to be deployed independently and concealed within individual tiers. When the chairs are in their retracted position, the tiered array of wood steps provides a unique social space and an interior landscape that encourages interaction.