W ARCHITECTURE AND LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE

EDITED BY BARBARA WILKS • INTRODUCTION BY ALISON HIRSCH WITH TEXTS BY BYRON STIGGE • DEBORAH MARTIN • STEVEN HANDEL PEGGY SHEPARD • JUDY KESSLER • ALLEN PENNIMAN • SUSAN TRAUTMAN

ORO Editions — Novato, California

INTRODUCTION 8 BY

ALISON HIRSCH

WHY DYNAMIC GEOGRAPHIES 10 BY

BARBARA WILKS

(IN)VISIBLE GEOGRAPHIES

13

TIDE POINT 18

WEST HARLEM PIERS 24

THE EDGE 32

MAINTENANCE: A CULTURE AND A CHOICE 40 BY DEBORAH MARTIN

MILL RIVER PARK 42

BUSH TERMINAL NORTH CAMPUS 44

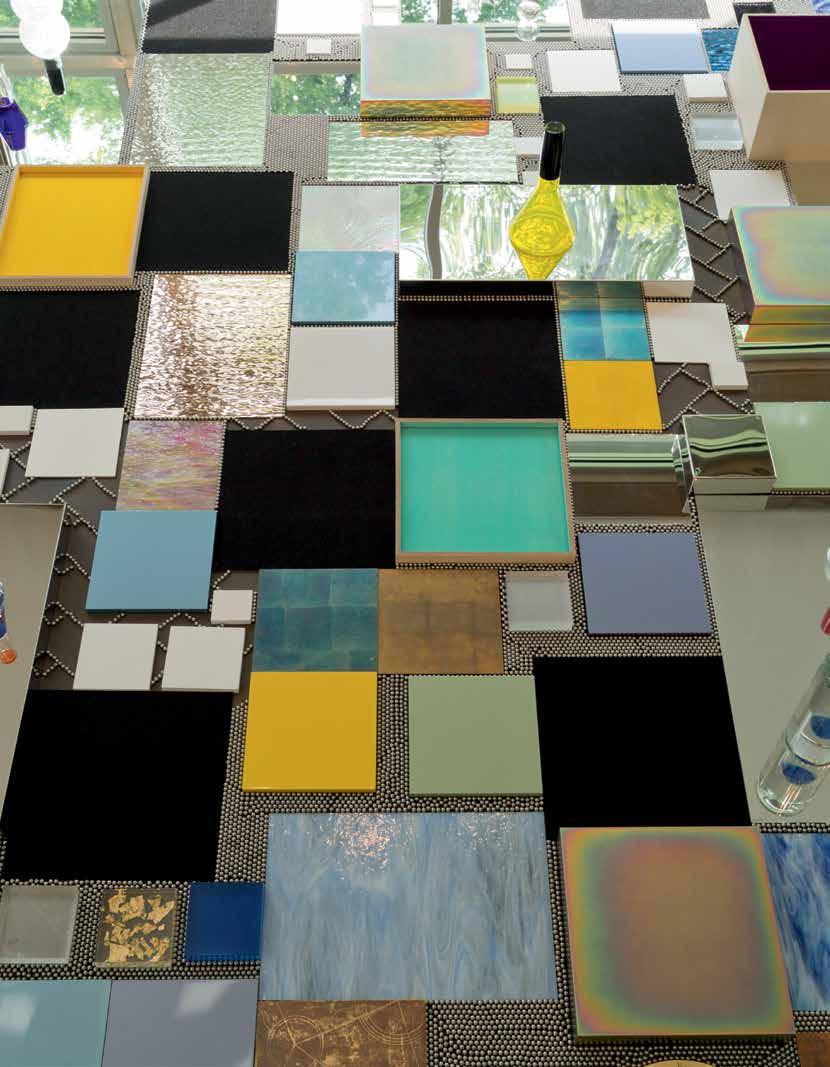

DOMA GALLERY 48

LAYERED GEOGRAPHIES 53

CHOUTEAU GREENWAY: ONE CITY BELONGING TO ALL 58

WHY TUNNEL WHEN YOU CAN PLANT! 64 BY BYRON STIGGE

JULIAN B. LANE PARK AND RIVERCENTER 66

JEFFERSON CHALMERS FRAMEWORK PLAN 72

FIVE BORO FARM II: SCALING THE BENEFITS 76

85 BROAD ST. GROUND MURAL 80

DOWNTOWN FAR ROCKAWAY + ROCKAWAY VILLAGE 82

PLAZA 33 86

UNLEASHING GEOGRAPHIES

93

ST. PATRICK'S ISLAND 98

THE UNSEEN STRUCTURE OF THE FOREST 108 BY STEVEN N. HANDEL

HIGH LINE TIME LINE 110

CORNELL HUMAN ECOLOGY BUILDING 114

PYRAMID HILL 116

ST. PETE PIER APPROACH 120

BLUE PIER 126

AFTERWORD 133

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 135

BOOK AND PHOTOGRAPHY CREDITS 136

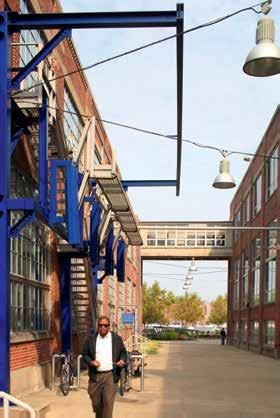

POST INDUSTRIAL LANDSCAPE — Remnants of the Proctor and Gamble soap factory remain surrounded by still-existing industry. Tank bases, steel armatures, and concrete walls stand as reminders of another time, repurposed for today. The concrete palette is continued in the new stadium steps, scaled to the industrial landscape and the pavement. Native plants and other hardy perennials have reclaimed the site, growing in the voids. In the almost 20 years since its completion, the site has transformed from a collection of start-up companies to the corporate headquarters of Under Armour, which bought the property in 2010. The basic site structure remains and the water is still the main attraction.

PEGGY SHEPARD, CO-FOUNDER AND EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF WE ACT —

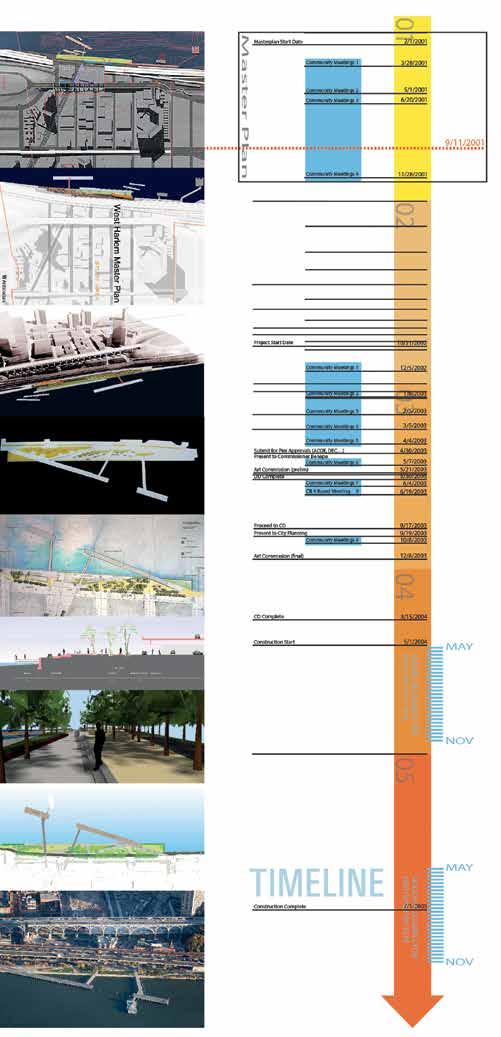

In 1998, WE ACT for Environmental Justice (WE ACT) partnered with New York City Community Board 9 to organize the Harlem-on-theRiver Project. Our goal was to engage community leaders and residents in developing a community-driven plan that would both increase access to the Harlem waterfront and raise interest in one of Northern Manhattan’s neglected neighborhoods. Working with more than 200 residents, elected officials, and representatives from the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, a community vision plan for the waterfront was developed and submitted to the New York City Economic Development Corporation (EDC) by WE ACT in 1999.

In late 2000, EDC scrapped its requests for proposals for commercial development at the site and developed a master plan based on the Harlemon-the-River community plan. Approval for the final West Harlem Waterfront Park plan came in 2003 and applications for construction were quickly completed. A groundbreaking took place in October 2005, and construction on the park was completed in late 2008. The park was officially opened as the West Harlem Piers Park on May 30, 2009.

Each summer since 2009, WE ACT has hosted the Black & Green Film Festival. We show films that focus on environmental issues impacting lowincome communities and communities of color, often preceded by a panel discussion. The park continues to serve as a greenspace for the community as well as an example of how a community can work together to ward off development and preserve a precious slice of the waterfront for public use.

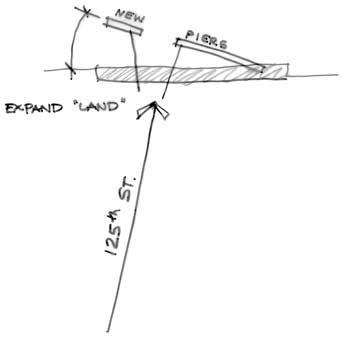

THE PIER DESIGN — The piers follow land formation patterns, rather than historical pier configurations that privilege the city grid. Gently angled away from shore, then divided in half to allow the axis of 125th St. to run through, these constructed piers provide for various water related activities including fishing, ecological awareness, excursion boating, and general recreation. The view down 125th Street to the water is open.

A CITY-WIDE CONVERSATION — The Great Rivers Greenway, the client for this competition, is a regional infrastructure provider, that also acts as a convener for the City and County constituents. In the case of this competition, they prompted a city-wide conversation on how to make an equitable greenway system to heal a divided city. It was instructive that three of the four competition contestants suggested in their presentations that there are actually four parks in St. Louis, not just the two cited (park to arch). This acknowledgment of the lack of investment in the northern parts of the city has led to the first phase of the actual project being located there.

Our first phase features the north-south Spring Avenue connector with the Valley Beeline heading from that point east to the arch. The Spring Avenue connector links the northern and southern neighborhoods to the city’s cultural spine, and the Valley Beeline brings hydrology back to the now industrial, paved

valley. Most significant for us was the linking of the repaired ecology with the elevated highway infrastructure: using the destroyer of the former African American neighborhood, Mill Creek Valley, as the means to its rebirth in the form of a covered trail, creates an opportunity to heal past wounds and bring the city together. St. Louis is a paradigm of the American city. From Pruitt Igoe, to the less well known and more successful LaClede Town neighborhood designed by Chloethiel Woodard Smith, to the construction of the interstate highway through the center of the city, it has been a part of the failed experiment in urban renewal and integration our country undertook in the ’60s. This project is a part of the healing still ongoing for this disruption.

SUSAN TRAUTMAN, CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER, GREAT RIVERS GREENWAY

Hosting an international design competition for our greenway project was a game-changer for us. First of all, it was a way for many parties to come together and rally around the possibilities. From partners to funders to neighbors to technical advisors, having the structure of a competition helped to galvanize excitement, momentum and consensus around a shared vision for the future.

Second, the competition invited us to introduce the project to the community and our partners in a way that put values and ideation first while setting the expectation that this would be different than our typical projects. We invited public engagement throughout the process with exhibits all over town, livestreaming presentations, and hosting events. This set the tone for the project as being big and bold as well as grounded, community-driven, and transparent. If we had begun the project like normal, we would not have gotten participation. Because we launched an international design competition, we built the beginnings of a movement of public support that will be the foundation for the project longterm.

Last but not least, getting perspectives and ideas from across the globe from the design teams, the competition manager and the jury really pushed our thinking locally. We had a bold vision and we welcomed creative approaches to bring it to life, both for the project and the process. Doing a competition means we can keep, build upon, and leverage all of those ideas no matter what; we have an arsenal of fresh thinking to pull from for years.

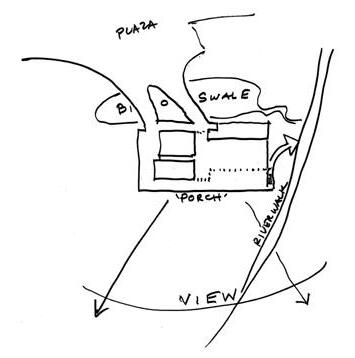

A RIVERCENTER THAT MERGERS WITH THE LANDSCAPE —The Tampa Rivercenter is set into a bluff adjacent to the Hillsborough River. This position allows access directly to the water from the boat storage on the ground level, as well as access from the park plaza to the upper level. The glass-enclosed upper floor is shaded by the roof, which also shelters the wraparound public terrace and directs rainwater to a bioswale rain garden, which collects and filters runoff returning it to the Hillsborough River. The Rivercenter is also part of the park experience, connecting the plaza via a bridge over the bioswale to a covered terrace overlooking the downtown. This porch thus not only expands the space of the Rivercenter but also allows for public park access to this upper story view even when the facility is closed. To create a safe place to launch boats, a new inlet was carved from the riverbank and the existing seawall was relocated inward. Surrounded by pedestrian wharf space, and protected by a long floating dock along the river, it provides safe and easy access to the water.

THE

LIVING ISLAND LANDSCAPE —

St. Patrick’s Island was designed as a Living Island, that is it is designed to support the development of healthy ecosystems, with their various types of plants and animals, as well as to provide spaces for people to enjoy. The lush, highly productive, wetlands, shrub-lands, and cottonwood, characteristic of this riparian zone, contrast sharply with adjacent semi-arid praire of the upland areas, common to Calgary and its surroundings.

A GREEN HEART — On this former street bed and parking area, we created a pedestrian oriented destination which links the downtown and the pier in a seamless experience emphasizing our relationship to the water and the environment. Our design situates the experience in a native pine/oak woodland, with lush gardens, unusual play areas, and linked ponds and bioswales set within it. A central lawn is the focus and location for an immense hanging net by artist Janet Echelman, and swirling circular pathways and forms reflect the karst topography beneath. The park design reduces roadway and parking and manages storm water on the site in a series of interlocking bioswales and ponds. Over 100 trees were carefully preserved. Attractive pedestrian uses are carefully choreographed to provide a series of events to lure people out toward the pier and Tampa Bay.