12 foreword

William Lie Zeckendorf

16 collaborator’s note

Joan Duncan Oliver

19 introduction

27 educating the master

29 Growing Up Zeckendorf

37 Learning the Business

55 on my own

57 Moving Up: The Mayfair House

62 Saved by a Dog: Hotel Delmonico

67 A Nightmare: The McAlpin

71 Easy Money: The Statler Hilton

74 Win Some, Lose Some: The Navarro, the Barbizon, and the Shoreham

77 the visionary

79 Opening the Broadway Corridor: The Columbia

87 Looking Up: The Park Belvedere

93 Win-Win with the A&P: The Copley

97 Location, Location: Central Park Place

106 At a Crossroads: The Alexandria

109 the innovator

111 A Noble Experiment: Delmonico Plaza

115 Selling Convenience: The Cosmopolitan and the Vanderbilt

118 Breaking New Ground: The Belaire

126 Downtown: The Hudson Residences

129 the transformer 131 Revitalizing Union Square: Zeckendorf Towers

142 Opening Up Eighth Avenue: Worldwide Plaza 161 A Capital First: The Ronald Reagan Building and International Trade Center 172 Turnaround in Queens: Citylights

181 the hotel maven

183 Lighting Up T imes Square: The Crowne Plaza Hotel

193 A Royal Mess: The Rihga Royal 199 A Crowning Achievement: The Four Seasons

231 santa fe: new beginnings

233 The Zeckendorfs in the Southwest: Return to My Roots

240 Nancy Zeckendorf: A Living Treasure

245 Scenic Views: Los Miradores

251 Successful Site Planning: Sierra del Norte

255 Introducing Luxury: The Eldorado Hotel and the Hotel Santa Fe

264 Restoring a Landmark: The Lensic Performing Arts Center

271 my passions

273 An Inherited Taste

277 Giving Back

281 Three Generations

287 summing up

291 epilogue Nancy Zeckendorf

294 afterword Arthur Zeckendorf

296 Acknowledgments

298 Index

304 Credits

My father, William Zeckendorf Jr., established his own real estate business in New York in 1972, and by 1994 he had moved on to retirement in Santa Fe, New Mexico. By most business standards this is a relatively short career. But few individuals have achieved more or changed more neighborhoods than my father did in that brief time. Developing: My Life chronicles those years. It is the story of a driven man who accomplished much. Sadly, my father passed away just as he finished writing the book. But his widow, Nancy Zeckendorf, has carried out his vision, guiding his memoir into print.

With the name Zeckendorf, it was inevitable that my father would go into real estate. By the time he joined his father’s company, Webb & Knapp, in 1953, my grandfather, William Zeckendorf Sr., was among the most famous developers in America. My father eventually became president of Webb & Knapp and played a significant role in such high-profile projects as Kips Bay Plaza, Park West Village, and Lincoln Towers

in New York, as well as Century City in Los Angeles and Place Ville Marie in Montreal.

After going out on his own in the early 1970s, my father acquired and renovated half a dozen hotels, then went on to build more than a dozen major condominiums, including the Columbia, Park Belvedere, Copley, Belaire, and Zeckendorf Towers in Manhattan and Citylights in Queens. For commercial projects, he built Delmonico Plaza and the mixed-use development Worldwide Plaza. Spread over four prime acres in Midtown Manhattan, Worldwide Plaza was the subject of a four-part pbs series, Skyscraper, that gave viewers an unprecedented inside look at the complex world of real estate development. My father also developed the Rihga Royal, Crowne Plaza, and Four Seasons Hotels. Periodically, Nancy would take him to New Mexico to relax, but he needed another outlet for his energies and developed five major projects in Santa Fe in his spare time.

There are a number of successful real estate dynasties in New York. However, what differentiates our family is that all three generations of us are self-made. That was certainly true for my father. By 1971, my grandfather’s business had collapsed, and my father had to start over with no company and no capital. One of the most important pieces of advice he ever gave me was: “To succeed in this business you can never look back.”

In those early summers when I worked for him, he was building a hotel portfolio that included the Delmonico, Mayfair House, and Statler Hilton. He paid close attention to back-ofthe-house operations and occupancy rates and did spectacularly well renovating hotel properties, improving operations, and then selling them at a large profit.

But when we spent time together on weekends or at night over a bottle of wine, he often said that what he really wanted to do was develop. Renovating and selling hotels was profitable but ultimately unsatisfying for him. The creative part of the business was development, and that’s where he was headed.

By the time I returned from business school in 1984, my father’s company had grown dramatically. He was now in full swing, and one project had turned into five, all going on at the same time. Over the next eighteen years he completed more than twenty buildings in Manhattan and Queens. In the process, he transformed neighborhoods from Union Square to Hell’s Kitchen, from the Upper West Side to Long Island City. Few developers have done more to revitalize neglected parts of New York than he did during those years.

My father would chase a deal, secure financing, and then pore over floor plans with the architect. But as soon as the first shovel hit the ground, he moved on to the next deal. My brother, Arthur, and I, or one of the other project managers on his ever-growing staff, would take it from there, overseeing construction and directing sales and marketing.

I spent a tremendous amount of time with my father in those years, looking for investors halfway around the world. Some of my fondest memories are the many trips we made to Japan for the increasing amounts of capital his ever-expanding business demanded. On one trip a massive earthquake knocked us both to the floor of the Imperial Hotel. On the next trip, a major typhoon hit. Wisely, our hosts stopped inviting us to Tokyo and came to visit us in New York from then on.

On another occasion we were desperate for a construction loan for Worldwide Plaza and had pinned our hopes on a major Canadian bank. On the day a senior bank officer whom we’d never met was scheduled to come to our office, we happened to have been invited to a lunch cruise aboard a friend’s yacht. We took the banker with us on the cruise, where he seemed to be especially fond of the bar and buffet.

After the cruise, we were almost back at our office before we realized we had forgotten the banker and left him stranded aboard the yacht. We were sure we’d blown our chances of getting any financing. But to our amazement, a week later a loan commitment letter arrived from the Canadian bank.

As my father’s creativity fueled his ambitions, all he wanted to do was build more and more. Money had never been of much interest to him, so it probably should not have been a surprise that when the recession hit the real estate market in 1991, he was undercapitalized. It was tough going for all of us, but my father handled this difficult time with amazing dignity, doing everything in his power to honor his obligations. By 1994, however, my father was ready to step back from real estate in New York, and soon thereafter he moved to Santa Fe.

I am thankful for the years I worked with my father and grateful for the many lessons he passed on. I will forever cherish the time we spent together.

William Lie Zeckendorf New York City, 2016

Introduction

I’ll never forget that afternoon in March 1988. The phone rang: it was Tom Javits, my project manager at the Belaire, a fortytwo-story apartment tower we were building on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. “We’ve got a problem, Bill,” Tom began. “A big one. You’d better get over here right away.” Tom’s not one to exaggerate, so I could tell it was bad.

The site was a ten-minute drive from our office, but my driver probably made it in half that time. When I got there, I saw Tom, the building engineer, and the excavation crew lined up along the rim of the hole, peering into it with worried looks. The excavation was nearly finished, but when the bulldozers had reached the outer edge of the site, the crew had discovered that the apartment building next door wasn’t resting on a foundation, just on mud and it was drifting our way. If we didn’t do something fast we’d have eighteen stories of brick and glass tumbling into our site.

Skyscrapers in New York City need to be anchored to bedrock to prevent settling. They generally rest on a reinforced-

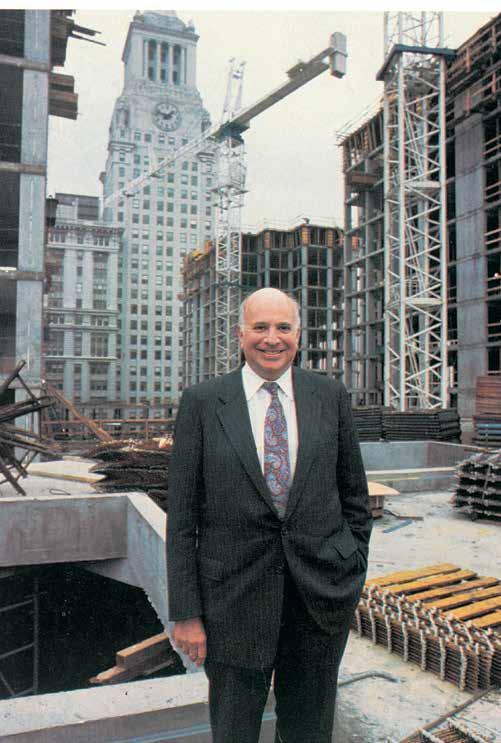

Bill Zeckendorf during construction of Zeckendorf Towers, New York, with Con Edison building in the background (opposite)

concrete foundation that sits on the rock. However, the apartment tower due west of us, which went up in 1963, wasn’t built to code. The mistake was theirs an illegal shortcut that had eluded the building inspectors but the problem was ours— under the city’s building codes, shoring up their building was our responsibility. So we had to stop work and underpin the leaning tower, setting us back four months. All the while, the clock was ticking on our construction loan. Thousands of dollars in interest were mounting while we put in a new foundation for the building next door.

But eventually, we finished the Belaire, and it was one of our most successful projects. We received kudos for the innovative design, and the luxury condos sold well. But the excavation delay wasn’t the last of our problems—not by a long shot. In the development business, that’s just the way it goes.

Not every job encounters the problems we faced at the Belaire, but the unexpected is to be expected. Crises, problems, overruns, delays: they’re all built into the cost of development. Putting up a building is never dull.

I learned that early on. I was born to the trade, after all. In his heyday, my father, William Zeckendorf Sr., was the most famous and successful developer in America a larger-thanlife presence who reshaped the skyline from one coast to the other. If you stand on the East Side of Manhattan and look west over Central Park, many of the buildings you see were built by my father. (You can see a few of mine there, too.) I started hanging around my father’s office when I was just a boy. As the years went on, I was thrown into some of the most exciting projects of the postwar building boom, with some of the best architects of the twentieth century. I.M. Pei got his start as my father’s in-house architect, and I still have the desk I.M. designed for Dad’s office.

My father was such a force, with such an outsized personality, that people sometimes aren’t aware that another Zeckendorf— his namesake at that came along right behind him. But I put my own mark on the New York cityscape with pioneering projects

that opened up marginal neighborhoods and overlooked sites. I was never the showman my father was, never had an in-house PR team at the ready, as he did. That’s not my style. But at the height of my career in the 1980s, I was the busiest developer in New York, and I never lost the thrill.

People often ask me what a developer does. Every project is different, I tell them, but generally it involves assembling property for a building site; finding equity partners and arranging financing for land and construction; working with an architect on a design; hiring a contractor to supervise construction and oversee subcontractors and construction crews; marketing the offices or apartments, selling and leasing them to potential occupants and dealing with any number of crises and setbacks along the way. When I explain this, the reaction often is, “Wow! Why would anybody want to go through all that?”

That’s not a question I ever asked myself during more than fifty years in the business. Though some projects were more interesting than others, some were more profitable than others, and some brought more challenges or headaches than others, I never doubted my choice.

Why did I find real estate development so compelling? The answer is simple: I wanted to build.

Developing is clearly in my genes. Though my father’s shoes were big ones to fill, I loved and admired him, and I learned a lot from him. His passion for development was infectious. With that and the name Zeckendorf, it was inevitable that I would end up on one side or another of the family business.

Still, people sometimes wonder, didn’t I ever want to break out and do something different? I can honestly say no. Sure, after I dropped out of college I briefly considered becoming a Broadway producer: I loved working backstage when I was in school. But I always knew that my best opportunity lay in working for my father. By the time I entered my teens, I was spending summers and school vacations working for Dad. And from the moment I picked up my discharge papers from the army, I

worked alongside him at his company, Webb & Knapp, until it folded in 1965.

After that, I went out on my own, forming what would become the Zeckendorf Company. Even then, my father remained a presence, advising me on properties and projects. And as soon as my sons, William Lie and Arthur William, were old enough, they came to work for me.

Over the past half century, I’ve renovated and built hotels, put up office towers and apartment buildings, and pioneered in emerging areas. I’ve earned a reputation as a visionary who could see potential where others couldn’t, whether in an oddly shaped lot or a rundown block. With my projects, I turned around struggling neighborhoods, improving life for the residents and paving the way for future development.

Ask me which project I’m proudest of, and I would cite a few, all quite different. The Columbia condominium was my first building from the ground up; it opened the Upper West Side to residential development and set off a building boom all the way down the Broadway corridor from West 96th Street to Union Square. On Union Square, I built Zeckendorf Towers, named for my father. A mixed-use complex, it seeded the rebirth of a once blighted area, transforming it from a haven for drug dealers to the thriving hub it is today home of the city’s largest greenmarket and a bustling crossroads of downtown New York life.

Eighth Avenue between West 49th and 50th Streets is the site of one of my largest projects, Worldwide Plaza; the office building and condo tower fill an entire four-acre city block. To upgrade this neighborhood, the infamous Hell’s Kitchen, we renovated rundown tenements, shut down drug dens, and razed sex shops and peep shows, making Midtown west of Broadway a viable location for blue-chip businesses and upscale residences.

And then there’s the Four Seasons, a luxury hotel on East 57th Street. This project gave me a chance to work with I.M. Pei, not only my father’s house architect for years but also a close Zeckendorf family friend. Assembling the site where the hotel

stands a patchwork of eleven properties is a textbook case in how to put together a development deal.

With a team of investors and partners, I worked for more than a decade on a massive government project, the Ronald Reagan Building and International Trade Center in Washington, D.C. After the Pentagon, it’s the largest office complex in the capital. I still remember the thrill of sitting on the dais with Nancy Reagan and President Bill Clinton for the dedication ceremony. I have a special soft spot for Queens West, the development project that opened the Queens waterfront for residential use. There’s a famous photograph of my father standing on a grassy knoll near the East River, with the United Nations Secretariat Building in the distance behind him. That spot is almost exactly where, decades later, we broke ground for Citylights, the first building in an urban renewal project that transformed an industrial wasteland into prime residential riverfront property. My dad assembled the land on which the UN was built, so whenever I see that photo, I feel proud of the part the Zeckendorfs played in international history.

Then there are the Santa Fe projects. I’m proud of these for many reasons, not least because my wife, Nancy, has been a guiding force behind them. A former principal ballerina for the Metropolitan Opera, she worked tirelessly for American Ballet Theatre and other cultural organizations while we were living

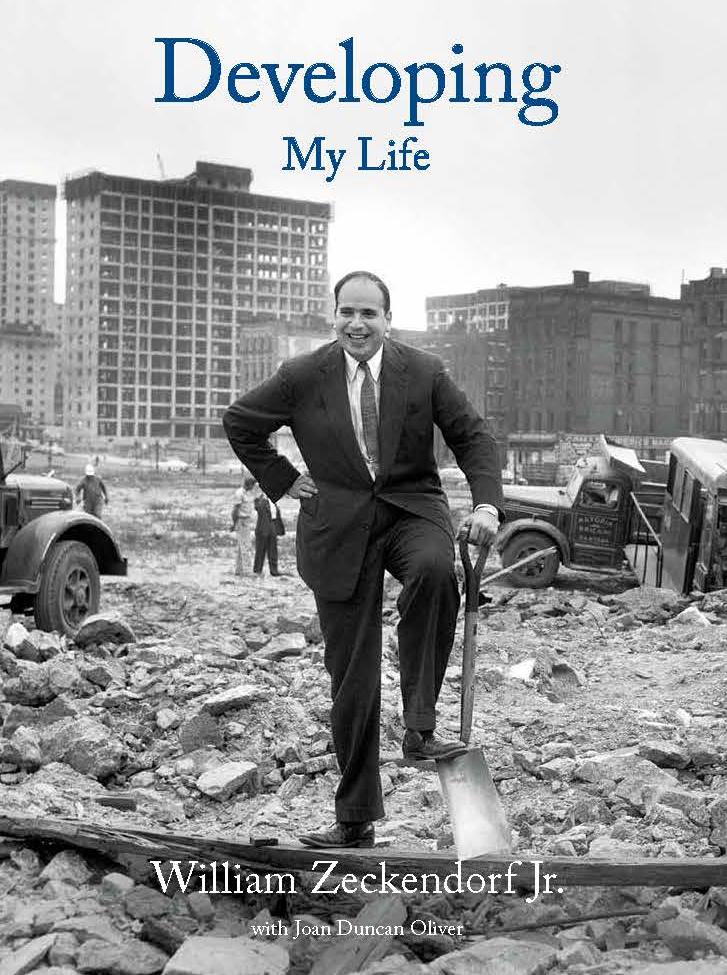

William Zeckendorf Sr. on one of his two car phones

in New York and then went on to reshape the cultural landscape of Santa Fe, New Mexico, by transforming the landmark Lensic theater into a vibrant, twenty-first-century performing arts center.

For years, I put off writing about my life in development. I’m pretty private, and I’d rather do something than talk about it. I figured my work could speak for itself. But now that a fourth generation of Zeckendorfs is coming along my granddaughter is in the class of 2016 at the Columbia Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, and my grandson is in the class of 2015 at Columbia Business School I feel a strong desire to set the record straight.

I’m my father’s son, but I’m not my father. I forged my own path, did my own deals, and raised two extremely successful sons who have built a multibillion-dollar business in residential real estate. My own career did not follow a straight upward trajectory. I’ve experienced setbacks and losses. I’m not a gambler,

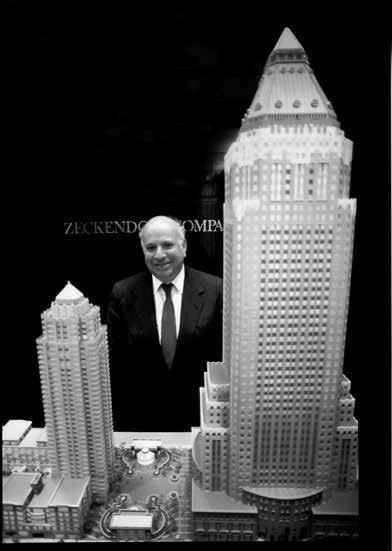

Bill Zeckendorf with a model of Worldwide Plaza

but real estate development is inherently risky, and I happened to be in the game at the end of the 1980s, when the market went south and took my holdings with it.

The Zeckendorf name opened many doors, sometimes in unexpected and unusual ways. I’m eternally grateful for that. But it was no protection against the vagaries of real estate or some of my partners. My father soared high and then fell spectacularly, like Icarus. In helping him close up his business, I vowed not to follow in his footsteps. Instead, I made my own mistakes before ending on a high note, with a second, satisfying career in Santa Fe. Along the way I’ve worked with exceptional people architects, contractors, investors, brokers, city planners, and a loyal and committed office staff. And through it all, Nancy has been beside me.

Developing: My Life is a legacy of sorts. I offer it to answer, at least in part: Who was Bill Zeckendorf Jr.? What did he build? And what did he discover along the way?