Editor

John T. Spike

Project Management

Giuseppina Leone

Layout and Typesetting

Evelina Laviano

Copy Editing

Doriana Comerlati

Prepress, Printing and Binding

Galli Thierry Stampa, Milan

© 2019 Verlag Scheidegger & Spiess AG, Zurich

© Carole A. Feuerman for all her works

© The authors for their texts

Verlag Scheidegger & Spiess

Niederdorfstrasse 54

8001 Zurich Switzerland www.scheidegger-spiess.ch

ISBN: 978-3-85881-844-7

This book has been printed using energy produced through a photovoltaic system – less CO2 in the environment.

Scheidegger & Spiess is being supported by the Federal Office of Culture with a general subsidy for the years 2016–2020.

All rights reserved; no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written consent of the publisher.

Photo Credits © 2019. The Metropolitan Museum of Art / Art Resource / Scala, Florence: pp. 30, 43 © 2019. Photo Scala, Florence: p. 22 top Alinari Archives, Florence / By concession of the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities: p. 34

Courtesy Amarillo Museum of Art: pp. 75, 80

Courtesy The Berkshire Eagle: pp. 124–25

Courtesy Robert Hurst: pp. 126–27

Courtesy 25th Edition of Sculpture Link: pp. 130–31, 138–39, 140–41

Carole A. Feuerman Studio: pp. 17, 18, 23, 76, 77, 82, 83, 84–85, 88, 102, 103, 114, 115, 123, 174, 180

Gallery Biba, Palm Beach, FL: p. 146

Iberfoto / Alinari Archives, Florence: p. 44

National Lampoon Magazine: p. 14

Jorge Alvarez: pp. 148–49

Raina K. Asid: p. 190

David Ashton Brown: pp. 1, 6–7, 8, 12, 24–25, 27, 28, 29, 31, 35 top, 36, 40,

58–59, 61, 63, 69, 70–71, 73, 87, 104, 105, 108–09, 111, 113, 116–17, 120, 128–29, 133, 134–35, 143, 144, 145, 147, 151, 154–55, 156, 157, 158, 159, 160, 161, 162–63, 164, 165, 166–67, 168–69, 170–71

Juan Cabrera: cover, p. 38

Alvaro Corzo: pp. 2–3, 4–5, 20–21, 46–47, 64, 65, 67, 68, 72 top and bottom, 91, 106, 107, 118–19, 121, 136–37, 188

David Finn: pp. 81, 89 Alessandro Moggi: pp. 15, 51, 52, 96, 97, 98–99, 100–01, 185

Dan Morgan: pp. 22 left, 35 bottom, 92, 93, 94, 95 Ellen Page Wilson: pp. 32, 48, 78–79, 86

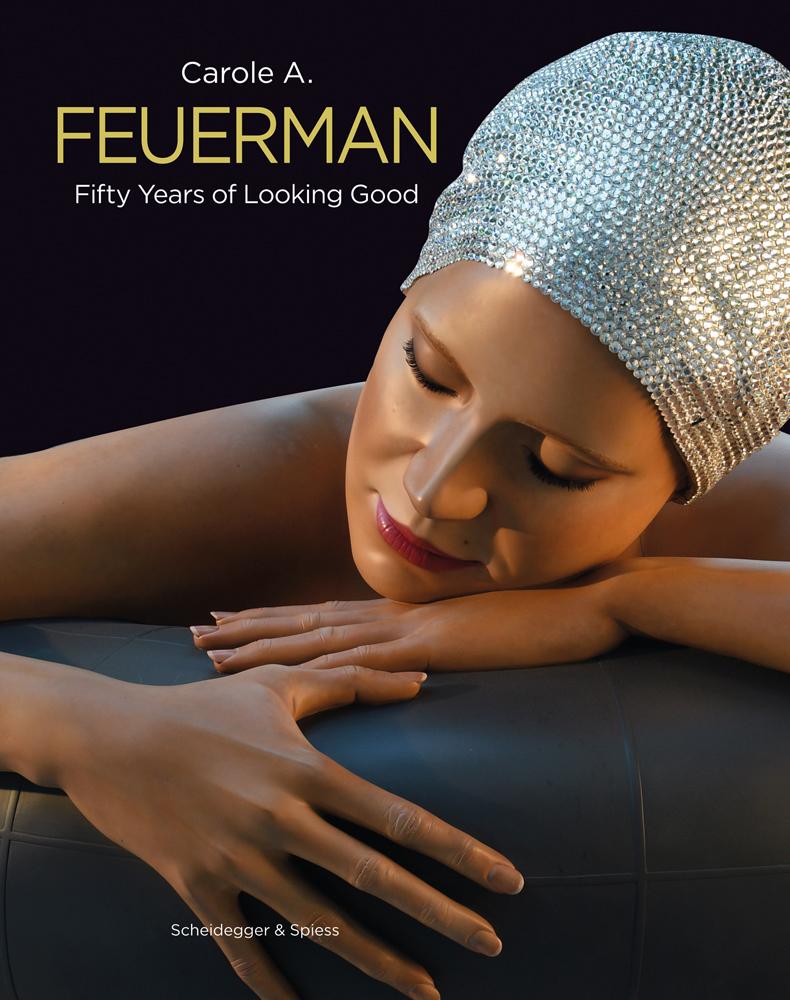

Jacket

Survival of Serena, 2006–2017 (cat. 35)

Cover Perseverance, 2019 (cat. 90)

Page 1

Infinity, 2014, detail (cat. 60)

Pages 2–3

The Golden Mean, 2012 (cat. 48)

Pages 4–5

Feuerman working on The Golden Mean, 2012 (cat. 48)

Pages 6–7

Monumental Quan at Lotte Palace, New York, NY, 2015 (cat. 68)

Page 8

Contemplation, 2018, detail (cat. 82)

Fifty Years of Looking Good

John T. Spike

Private Ecstasies / Public Art

John Yau

Carole Feuerman’s Art

Verisimilitude, Aesthetic Value, and Artistic Freedom

Claudia Moscovici Works Venice

Fifty Years of Looking Good

John T. Spike

In August of 1977, a young, talented illustrator sat down on Jones Beach, Long Island, to do some thinking. At thirty-two years old, Carole Feuerman was ten years into an award-winning career as a commercial artist in New York City. Married and divorced, with three children, she was working day and night to keep all the pieces together. Now she was also contemplating a major change. Could she leave illustration behind and begin a new career in the arts, as an independent sculptor of her own ideas?

Sitting on the beach, she saw a swimmer emerging from the sea, waterdrops streaming down her face. “She looked proud, like she had just accomplished something great. With goggles, hair slicked back, I saw her step out of herself and come into a new reality. Then I figured out how to do it. That woman gave me the idea to make my first swimmer sculpture, Snorkel .” Three years later, she made a second swimmer, this time sparing the snorkeling props, and focusing her attention on the young woman’s radiant, glistening face. She gave the sculpture the name of an island, Catalina.

Fifty Years of Looking Good is the fourth substantial book about Feuerman’s career, which has been on a continuous upward trajectory for decades now, as these copious pages will attest. Her childhood propensity towards art, family history, schooling, success as an illustrator, and first two decades in sculpture were admirably described in an essay by Eleanor Munro in her first book, Feuerman Sculptures, 1999 (2nd rev. ed., 2010). Through the years, Feuerman’s work has also received attentive interpretations by leading critics such as Robert Kuspit, John Yau, Peter Frank, David S. Rubin, Stephen C. Foster, Edward Rubin, not to mention the present writer.

After fifty years it seems right to single out a few “defining moments” in the career of this important living artist. These moments mostly take place over years: indeed the last, no. 7 in this list, is still underway. Rather than exhibitions or sales

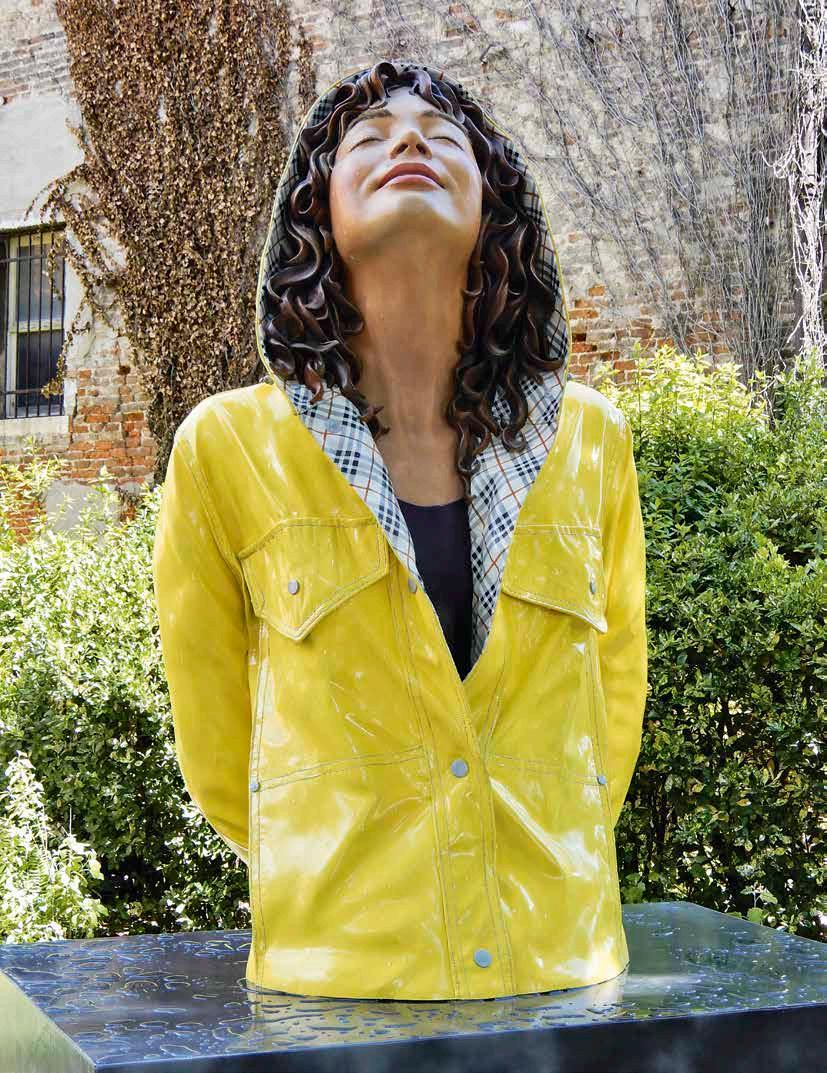

Chrysalis, 2017, detail (cat. 77)

Yaima and the Ball 2016 (cat. 74)

Kendall Island, 2014, detail (cat. 61)

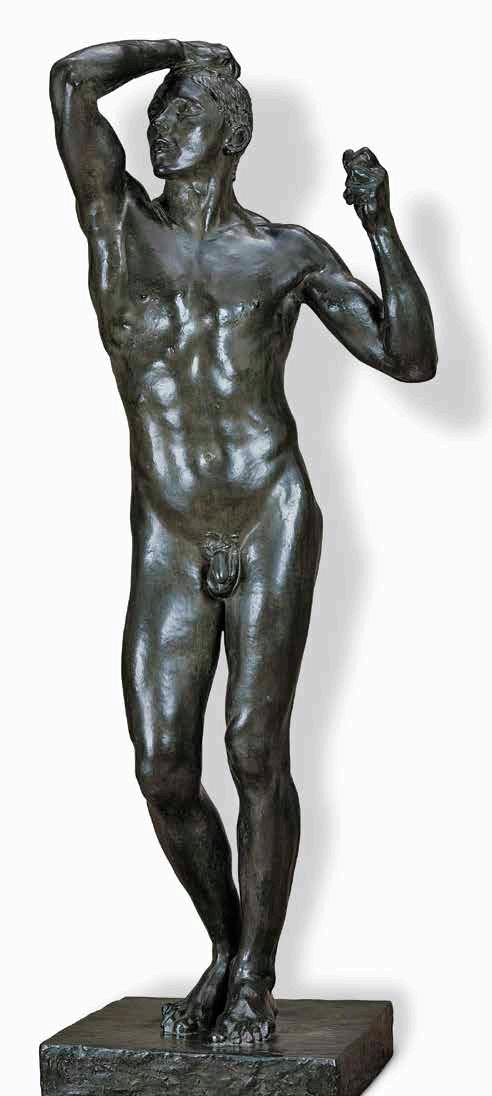

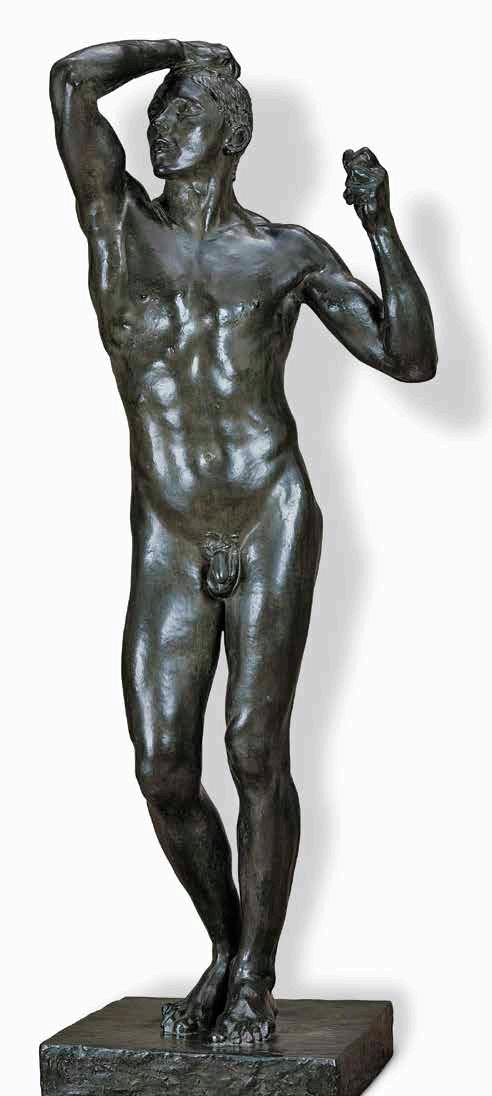

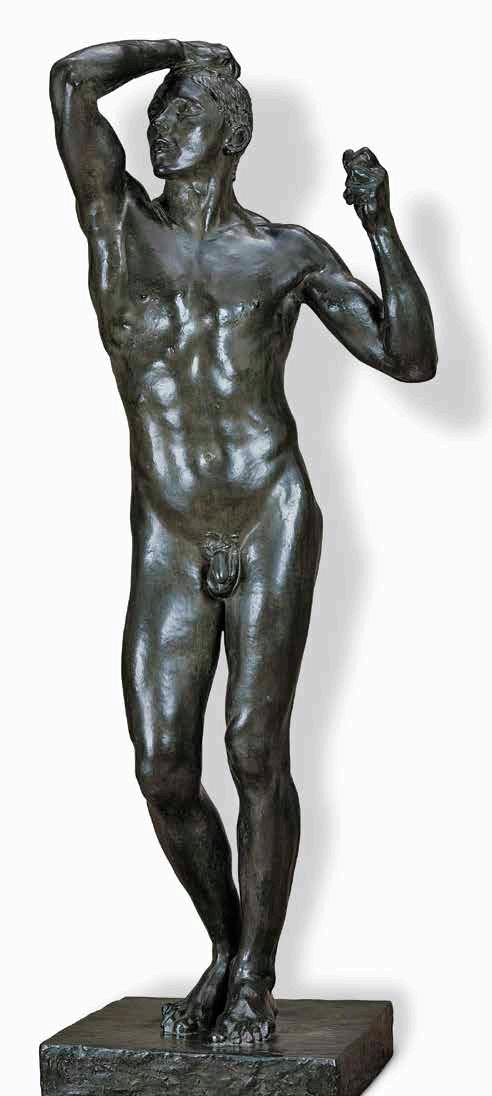

Auguste Rodin

The Bronze Age (L’Âge d’airain)

Modeled in 1876; this bronze cast c. 1906 by Alexis Rudier H. 72 in. (182.9 cm) Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Gift of Mrs. John W. Simpson, 1907. Acc.n.07.127

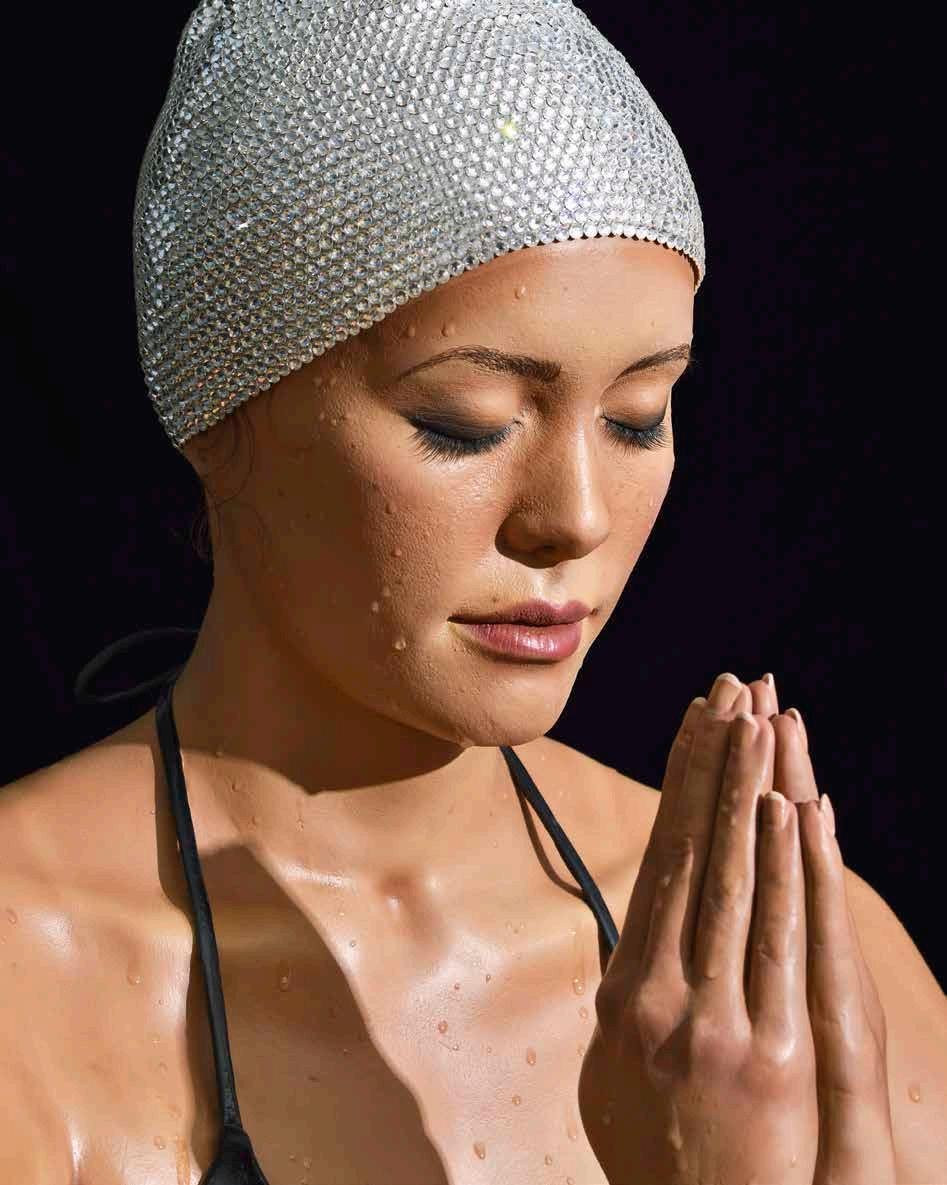

Page 31 Christina, 2013 (cat. 52)

Two other new sculptures, Kendall Island and Yaima and the Ball were brought by a civic arts group, Sculpture for New Orleans, for two-years’ residence (2015–17) in the rain and shine on a major traffic artery, the Poydras Corridor. Their names tell different stories: Kendall is an island in the Canadian arctic; Yaima gained her athletic physique on the Cuban national volleyball team. Both personified the best kind of public park statuary today – monuments to human perseverance and well-being.

Finally, this year, 2019, Carole Feuerman unveiled in the Giardino della Marinaressa a huge, pensive, monumental sculpture that, for obvious reasons, she named The Thinker. It was not her purpose to re-create Auguste Rodin’s masterpiece, but as she sought to make a strong, seated pose for a man, the result was a dynamic Thinker. The fact is, all Western figurative sculptors hold inside indelible impressions of the great precedents of Rodin, Michelangelo, and the classics. If proof were needed, compare the pose of Christina , first exhibited in Houston, Texas, in 2014. This dignified swimmer of perfect posture represents the sculptor’s subliminal homage to Rodin’s great Bronze Age of 1876. Rodin was accused being too lifelike, but history discerned its emotional depth. Forty years ago, showing healthy, intelligent women was a radical departure in contemporary art. Now it is a widely accepted ideal. Like great sculptors before her, Feuerman is not interested in life-likeness as a final goal. “Every work is a story,” she says.

Furthermore, as an aesthetic philosopher, I see a lot of value in the centuries-old tradition of verisimilitude that, with the advent of photography, some critics declared gone for good. As Feuerman’s success indicates, fortunately, verisimilitude, so often avoided by critics nowadays, is making a comeback. I would like to examine briefly the role of verisimilitude in the history of art to place in context the significance of Feuerman’s sculptures in the art scene today. I will argue that in order to have genuine artistic pluralism in the contemporary art world – where diverse styles of art are perpetuated and embraced by critics, curators, and the general public – it is necessary to value realist and hyperrealist art, such as the sculptures of Carole Feuerman.

Verisimilitude in Art

The aesthetic revolution that occurred during the twentieth-century is unprecedented in the history of Western art. Even the invention of one-point perspective and the soft shading that gives the illusion of depth (chiaroscuro) during the Renaissance did not change aesthetic standards as radically as the creation of non-representational, or what has also been called “Conceptual” art.

Since Andy Warhol’s Pop Art we have come to accept that brillo boxes and other ordinary household objects, if placed in a museum, are objets d’art And since Jackson Pollock and the New York School of Abstract Expressionism we have come to realize that what may appear to be randomly spilled paint, globs, and other kinds of smudges are not only artistic, but also considered by many to be the deepest expressions of human talent, thought, and feeling.

Once art took a conceptual turn, it also became philosophical. As the art critic and aesthetic philosopher Arthur Danto argues, in representational art what constituted “art” was more or less obvious. The only question that was more difficult to determine was: is it good art? By way of contrast, Danto explains, Conceptual art compels viewers to think about the very nature of art. The postmodern answer to this question is not only philosophical – namely, that art is a concept because it cannot be identified visually, just by looking at it – but also sociological. Art is, as Danto himself declares, whatever the viewing public and especially the community that has the power to consecrate it – by exhibiting it in galleries and museums, buying it, writing books about it, critiquing and reviewing it – says it is.

A priori, art can be anything. A brillo box, a toilet seat. But it is not everything for the simple reason that not everything is consecrated as art. What

Bibi and the Ball, 2017 (cat. 75)

Scuba, 1984 (cat. 7)

City Slicker, 1986 (cat. 10)

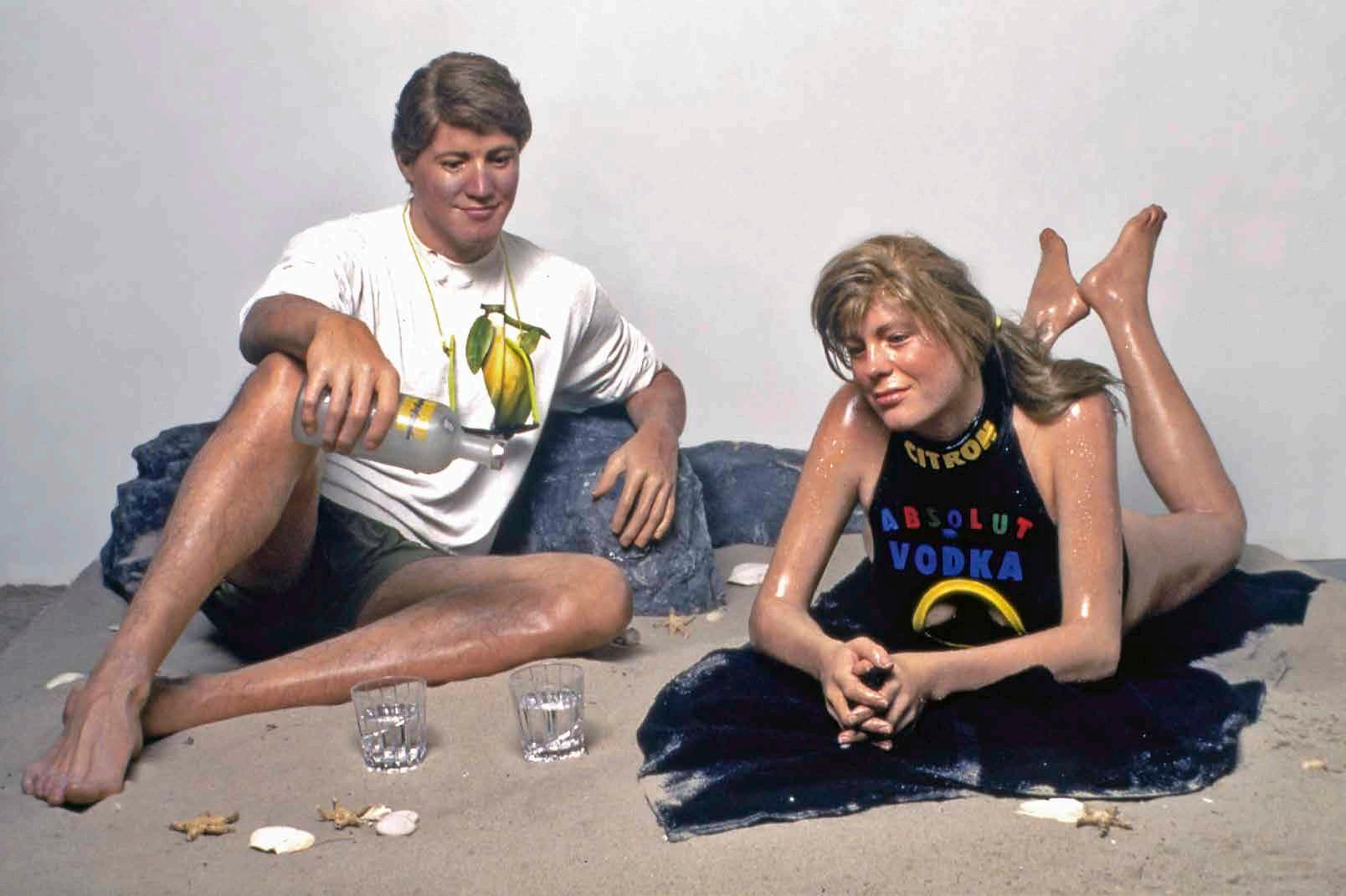

Absolut Summer Installation, 1992 (cat. 17)

Pages 104–05

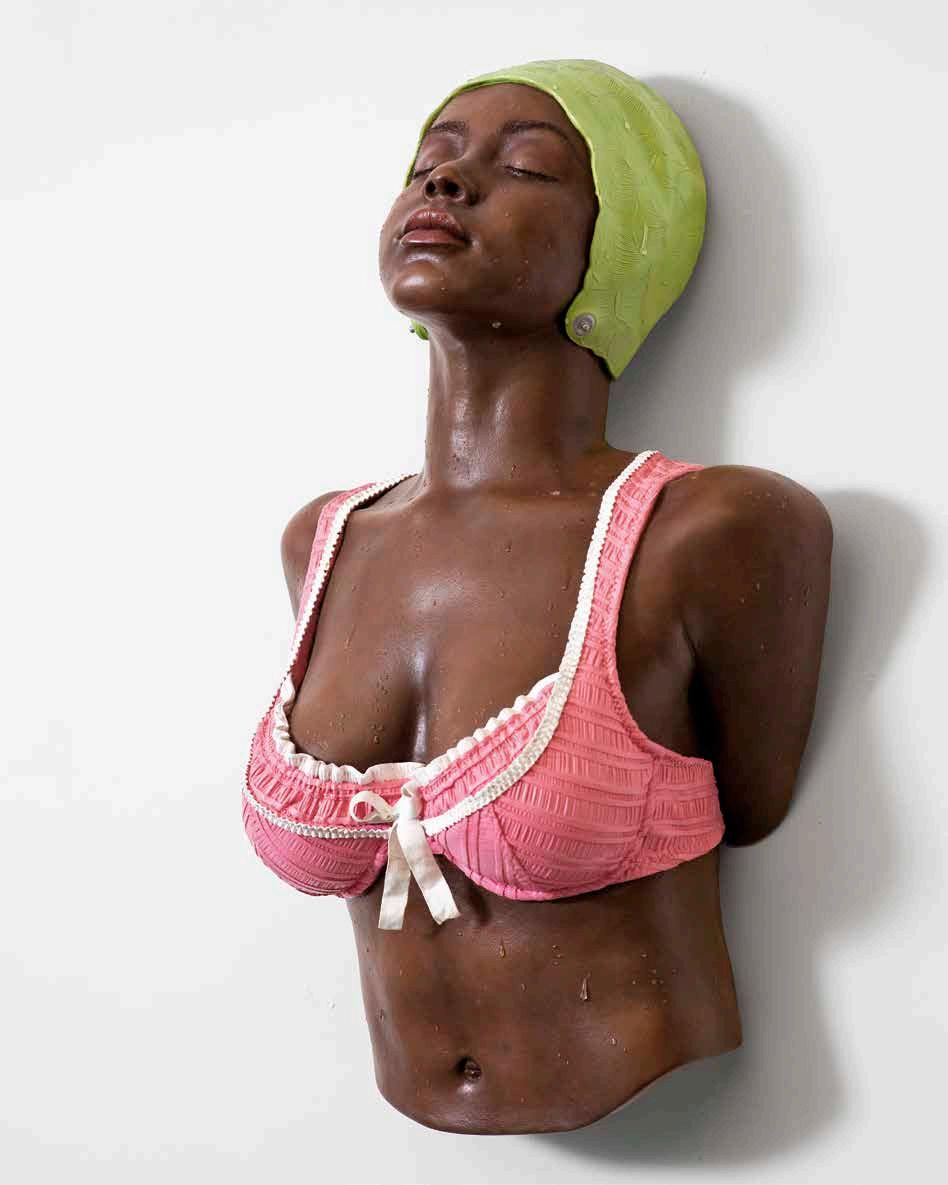

Capri with Swarovski Crystal Cap, 2012 (cat. 45)

General’s Twin, 2008, detail (cat. 36)

General’s Twin, 2008 (cat. 36)

Leda and the Swan, 2014, detail (cat. 63)