FOREWORD

by Jillian Walliss

LANDSCAPE AS ART

Landscape Painting

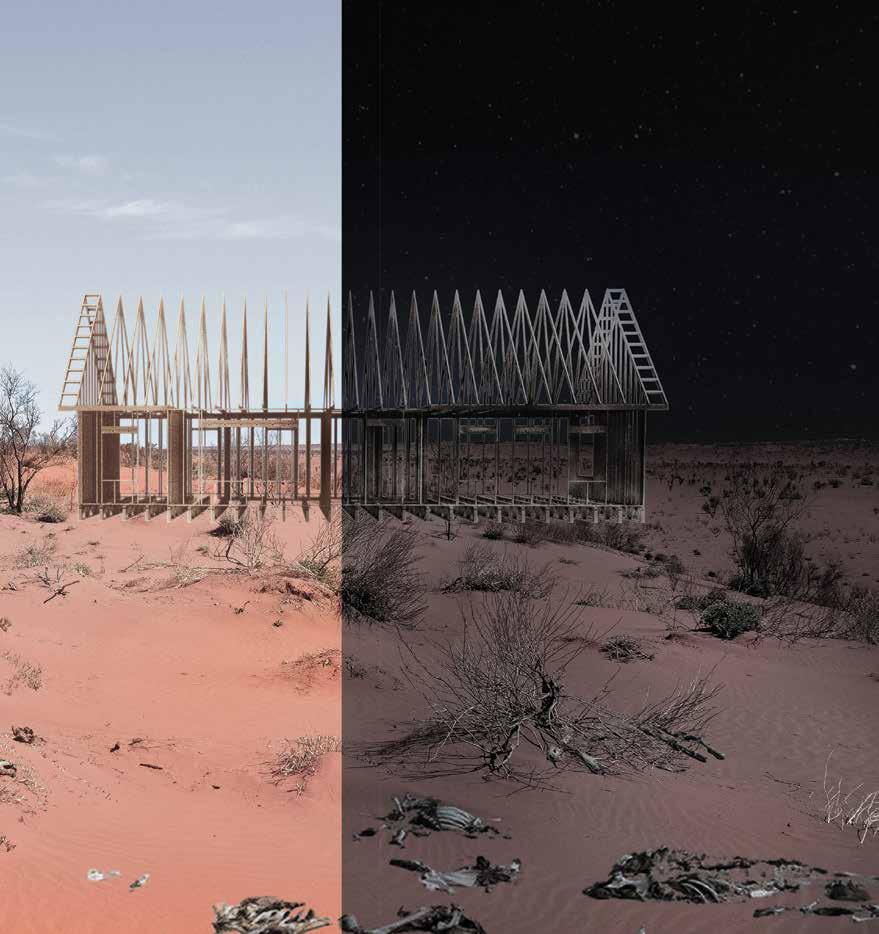

The Ghost House

Australian Garden

No-man’s land

The Berlin Room

Potsdamer Platz Park

Paris-Moscow Songline

The Herbal and the Bestiary

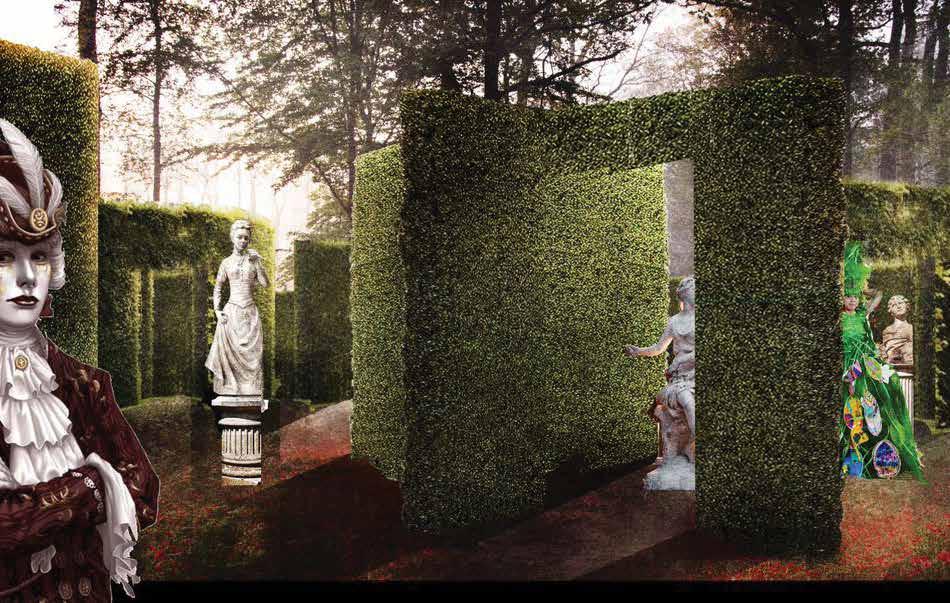

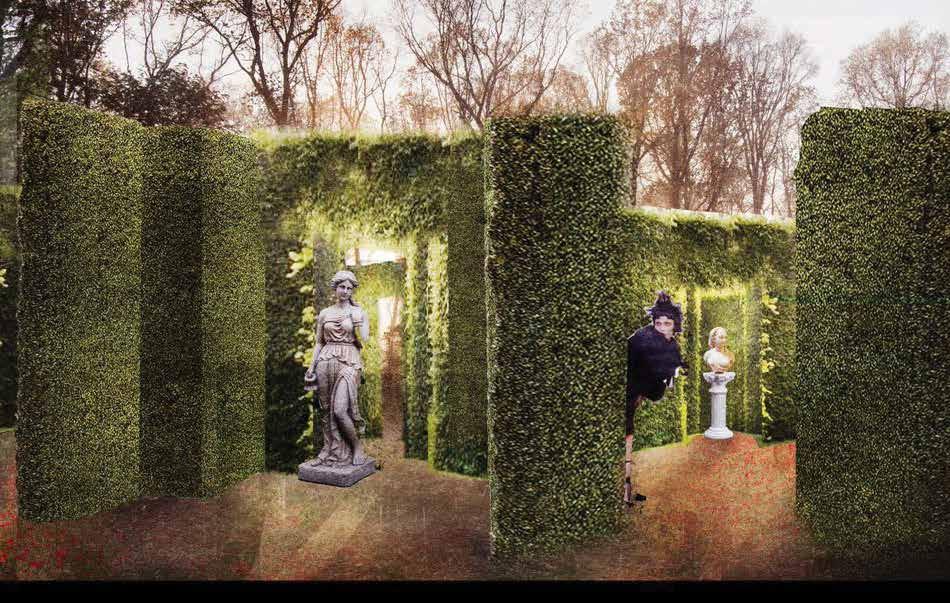

The Women’s Rooms

Decomposition

Île des Machines

Deutsches Institut für Normung

Animale Ignoble: Cockatoo Island

National Museum of Australia

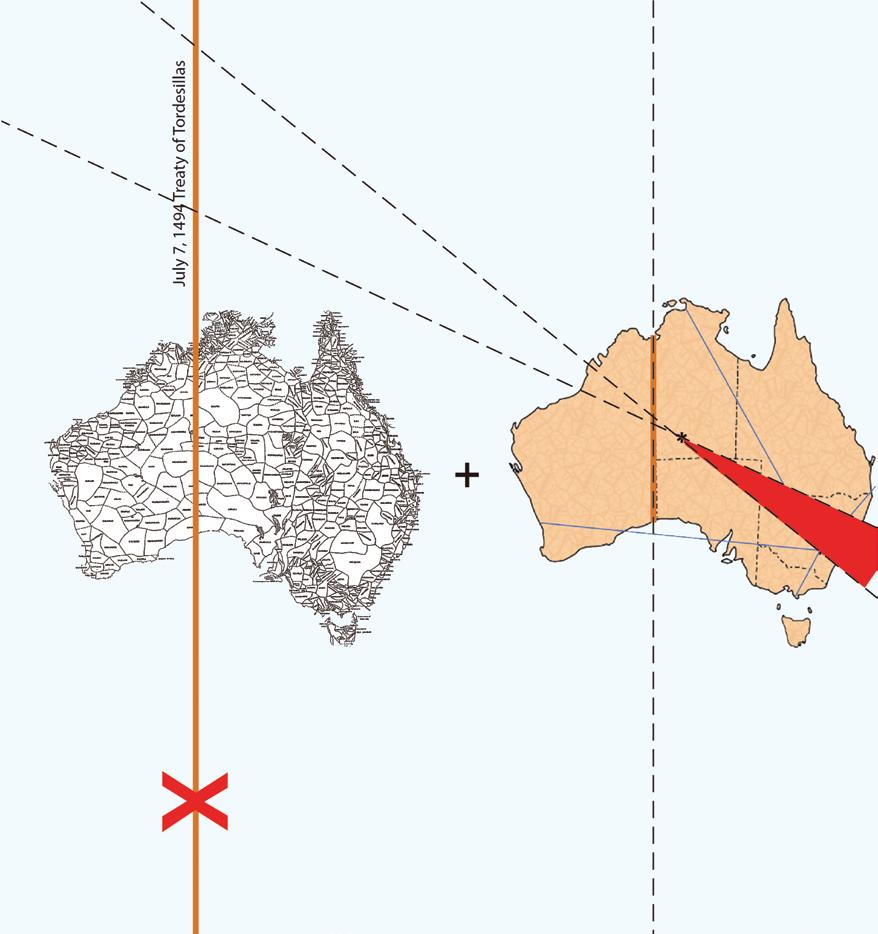

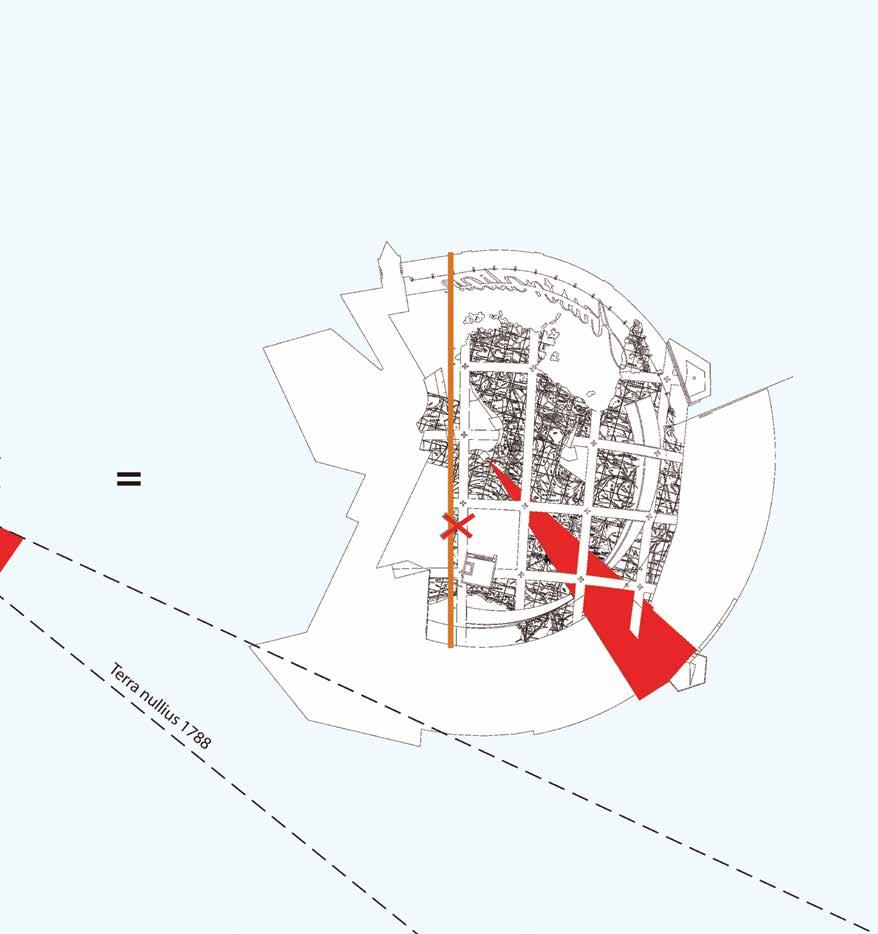

The Uluru Axis

Garden of Australian Dreams

Future Generations University

The Pentagon 9/11 Memorial

The Tsunami Memorial

The Course of Empire Circuit

Garden of the Anthropos

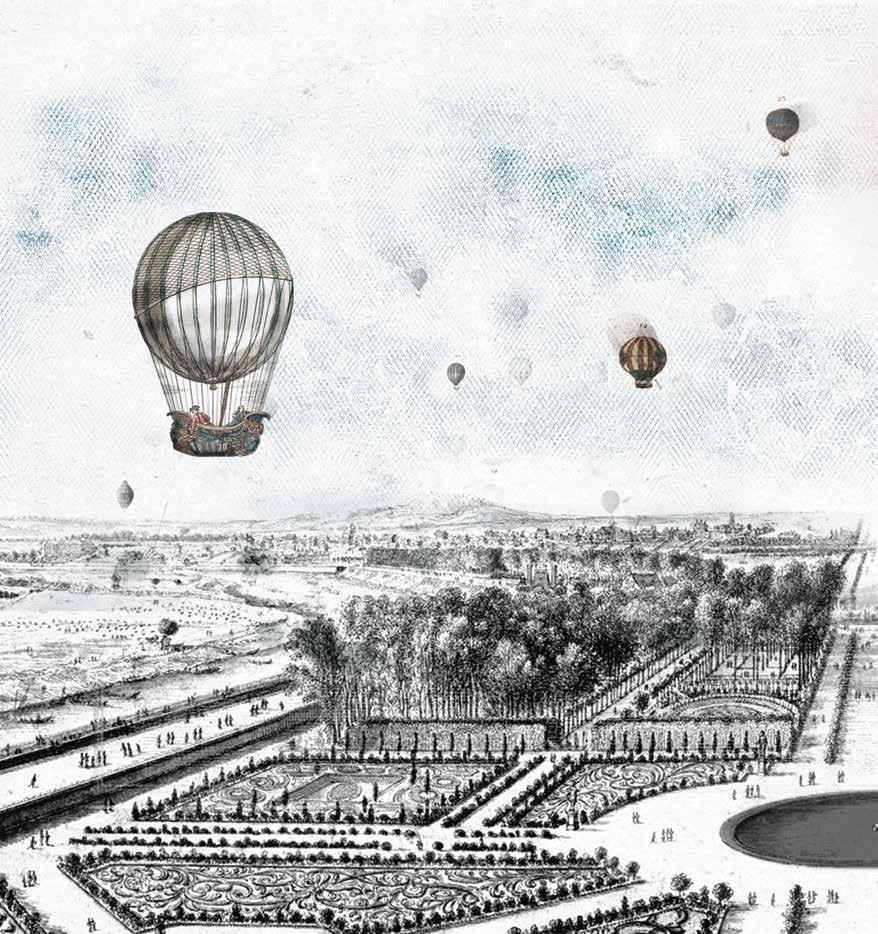

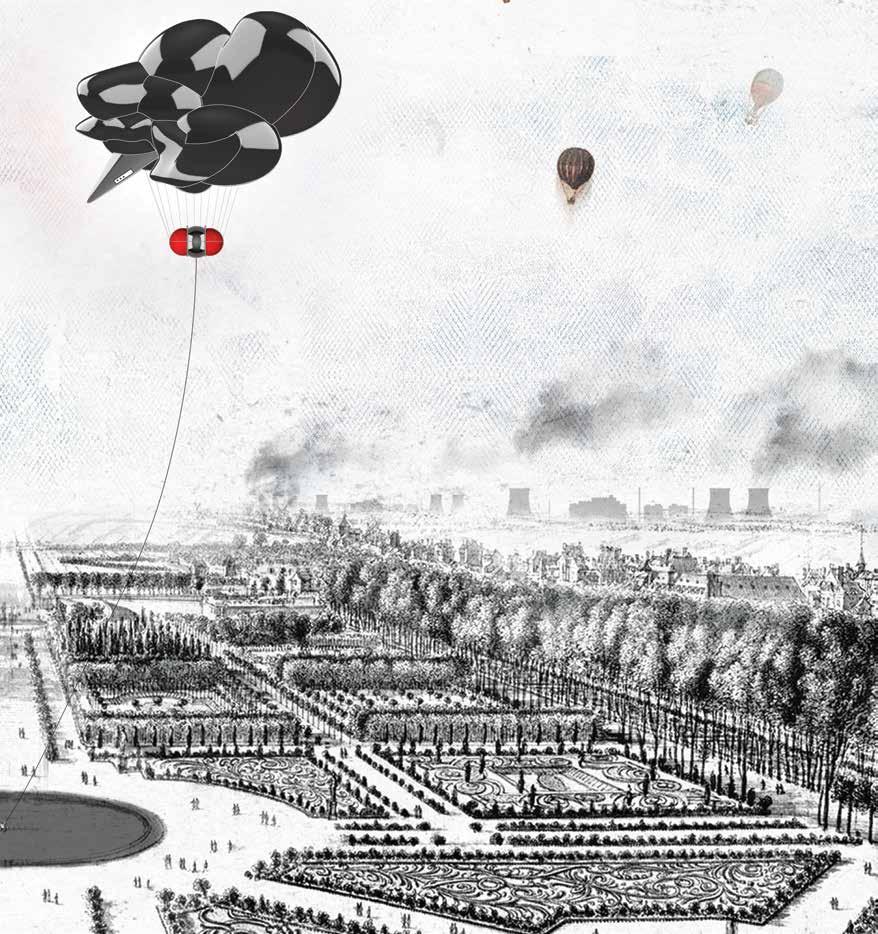

Weather Balloon

ESSAY

by Richard Weller

LANDSCAPE AS INSTRUMENT

The new suburb of Wungong

Boomtown 2050

GOD: Green Oriented Development

Made in Australia East and West Coast Megaregions

Roma 20-25: Lifecycles of the Metropolis

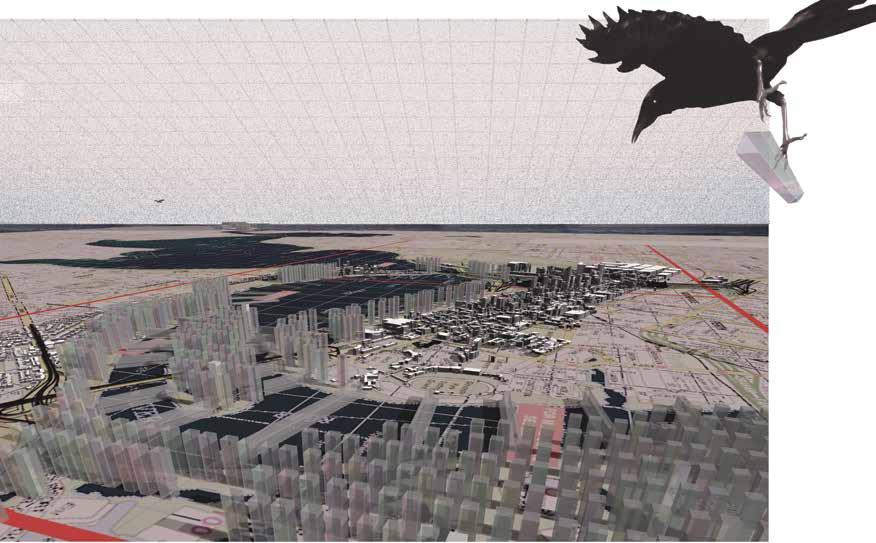

The Atlas for End of the World

The Problem of the Two Worlds

Biodiversity Hotspots

The Hotspot Cities Project

Bogotá 2050

The World Park Project

Mega-Eco Projects

The Butterfly and the Locust

Not the Blue Marble

AFTERWORD by Dirk Sijmons

Most celebrated designers and academics have a good origin story: graduating from an esteemed design school or scoring a breakthrough moment working in a major designer’s office. Richard’s career has no such story—a rarity in the design disciplines, where networks and affiliations underpin much individual success. Shaped by a deep interest in design and a dose of serendipity, his career has taken him from Sydney to Berlin, to Perth, and to Philadelphia, with many side trips along the way.

Australians have a strong sense of the periphery and the center. Occupying the center does not come naturally to antipodeans, and risks the dampening of original insights gained from being on the fertile edge. Richard’s influential iconoclastic views of landscape architecture in the 1990s and 2000s constructed from Perth—the most isolated capital city in the world—reflect these advantages. Forty years since his first exposure to landscape architecture during his studies at the University of New South Wales, 2 he is now in his final term as Chair of the Department of Landscape Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania, part of an esteemed lineup spanning Ian McHarg, Anne Whiston Spirn, John Dixon Hunt, and James Corner. In this role, Richard has managed to maintain his independence, work ethic, criticality, and Australian accent. Through projects he continues to speculate and provoke, capitalizing on his prominent position to lobby for a

globally driven landscape consciousness: a McHargian-influenced visionary with a Bob Geldof presence. 3

Competitions are the “Arte Povera” of the Periphery 4

Good design competitions are a mirror to the issues of our times and play a critical role in extending and challenging academia and practice. In many ways, design competitions, rather than formal design education, have shaped Richard’s career and craft. Writing in 2005, he commented that “by virtue of anonymity,” design competitions “allow one to transcend rank.” 5 Competitions helped Richard, a “blow-in” from Australia, to get a foot in the door of Berlin design firm Müller Knippschild Wehberg (now Lützow 7). But even more importantly, the competition format has honed Richard’s practice, offering concise provocations to explore via theoretical and creative speculation. Through the strict limitations of the competition, Richard has developed his signature approach—a manifesto-like proposition communicated through a compelling graphic and narrative.

Competition briefs provided Richard with an opportunity to directly engage with the impossibilities of absence in postwar Berlin (explored over a four-year period); the events of 9/11 (which many claim as the end of postmodernism); the experiential potentials of Sydney’s postindustrial harbor sites; the enormity of loss inflicted by tsunami; and the culture wars of Australia. He has taken students on this journey using competitions in studio teaching and more recently conceiving competitions for LA+ Journal . In this later incarnation, Richard has become the author of angst, challenging academics and practice to grapple with the (im)possibilities of the Anthropocene.

But it is in the story of The Garden of Australian Dreams (GOAD) in the National Museum of Australia that the double-edged sword of design competition success becomes evident—the initial accolade is tempered by the challenges and tensions of manifesting speculation into the physical. In this case, construction collided with the heated culture wars of late twentieth-century Australia. Not for the fainthearted, the debates over GOAD crossed national politics, academia, the profession, and the public. Who would have thought representing the “lucky country” could be so fraught? As Australia moved past the limp celebrations of the 1988 Bicentennial to construct a postcolonial identity of multiculturalism and pluralism, it failed to acknowledge its treaty-less foundation. Charged with constructing a new postcolonial national museum in the heart of the

nation’s capital, Canberra, this collaboration between architects ARM and Room 4.1.3 (Richard’s design practice with Vladimir Sitta), pulled off the many band-aids patching up Australia’s national identity.

Their design response was not the celebration that conservative politicians and academics had hoped for. Hidden amongst the symbolism employed in the GOAD were high and low cultural references, barbs, and provocations. The incorporation of the word “sorry” expressed in braille on the façade of the museum pushed many over the edge, leading to calls for the redesign of GOAD. This morphed into debates over the moral rights of designers—the first time that Australian landscape architecture had entered this arena. 6 The garden remains intact, although a little worse for wear as its colored-concrete ground surface fades (hopefully) alongside the conservative racial politics of Australia.

Twenty years on, there is a new competition for the heart of Canberra’s Parliamentary Zone, to be known as the Ngurra precinct. 7 Conceived against the political backdrop of Reconciliation, the emergence of state-based treaties and rumblings of an Indigenous voice to parliament, this competition represents a national maturing where direct Indigenous representation and input (rather than passive symbolism) will shape the outcome. At the time of writing, the winner is yet to be announced, but given a newly elected Labor government, the process should be somewhat smoother than the controversy surrounding the National Museum of Australia. As the saying goes, “you can’t make an omelet without breaking some eggs,” and GOAD offered a timely provocation during the uncomfortable process of reconciling Australian national identity with unfinished business.

At a more personal level, Richard acknowledges that such a close collaboration with architect Howard Raggatt (ARM) is a rare experience and served to amplify ideas. The project also garnered international attention, and was a catalyst for the publication of the Room 4.1.3. monograph by Penn Press in 2005. The value of GOAD— and the National Museum of Australia more generally—is far greater than its physical form, inspiring extensive professional, academic, and public discourse crossing Australian history, cultural studies, museum studies, architecture, urban design, and postcolonial theory. Arguably, GOAD might be the most discussed landscape architecture project in Australia in the past fifty years, if not since Walter Burley Griffin’s plan for Canberra.

A Designer in Wolf’s Clothing

The relationship between planning and design continues to be a source of tension in landscape architecture, splintering landscape praxis into the two camps of repeatable analytical methods and more-creative design speculation. In my conversations with American academics, Richard is often described as a planner. From an Australian perspective this is surprising, given that he is strongly identified as a designer and driven by an equally strong conceptual art practice. 8 This disputed identity is partly driven by the Australian understanding of the term “planning,” which conjures up images of imported British town planning ideals guiding the development of our cities and suburbs through green belts, subdivisions, and rational road systems. But when considered against the North American landscape planning tradition, Richard’s speculations on urbanism make the description of planner somewhat less design averse.

In 2005, Richard’s new role as director of the Australian Urban Design Research Centre (AUDRC) at the University of Western Australia, reoriented his focus toward the slippery challenges of an Australian urbanism. He identifies as part of the early twenty-first-century push toward conceiving a landscape-driven urbanism (although aligned with the North American landscape fraternity rather than the AA parametric flavor). Working within the research context of Australia, where money is tight, and grants are highly competitive, he began with the potentials of Perth’s suburban housing. Supported by a modest team of PhD candidates and researchers, Richard spent eight years interrogating Australian urbanism across the scales of the suburb, the city, and the megaregion. Mapping is critical to this practice, and unquestionably Richard loves a map. Historical maps offer a host of cultural and political references, while landscape architecture’s beloved GIS provides a comprehensive inventory of spatialized physical and social data. When applied critically and creatively, mapping offers a generative technique for merging planning and design, which Richard and his team used to great effect in their foray into urbanism.

Over time, he managed to wrangle the world of Australian competitive research grants into his preferred mode of design speculation. Boomtown 2050: Scenarios for a Rapidly Growing City , funded by a three-year Australian Research Council grant, presents alternative design scenarios for Perth’s urban development. Published in 2009, the research aimed to graphically present density speculations with

a detached neutrality, hoping to prompt a wider debate engaging politicians, the public, built environment professions, and the media. Boomtown morphed into a major communications exercise with Richard delivering up to four lectures a week outlining future scenarios for Perth’s urbanism. Here the graphic images count—offering a far more accessible story than conventional planning documents.

However, this urban development story inevitably must include economic growth in its plot. And therein lies the failure of landscape urbanism: its agendas are most easily realized in the excess space of the shrinking city, or alternatively in China, where technically no one owns land, and the government operates as developer and authority. In an Australian urban growth model, where the economy is underpinned by the construction industry, it is extremely challenging to bring questions of biodiversity and ecology into the urbanism equation. No art of instrumentality here—just the blunt instrument of short-term economic growth. Richard’s 2008 essay “Landscape (Sub)Urbanism in Theory and Practice” oozes with this frustration, drawing attention to landscape urbanism’s lack of engagement with the suburb, including the economic realities “where developers, service providers, and ultimately consumers all operate within narrow financial margins.” 9 As Richard reflects, “large-scale urbanism is a fool’s game”—as you move away from discrete design projects to the larger scale you inevitably lose control.10 There is a vast gap between landscape urbanism as a theoretical concept and a constructed reality.

Building Penn’s Landscape Legacy

In the world of landscape architecture academia, the chair at the University of Pennsylvania (Penn) is the holy grail. Past chairs have demonstrated Penn’s openness to non–North American candidates, as evidenced by Scotsman Ian McHarg and Englishman James Corner. Or have they? This claim is only partially true, given that both McHarg and Corner studied landscape architecture at Harvard and Penn respectively.11 The appointment of Richard in 2013 was far more of an unknown, gained without the advantages of an East Coast landscape pedigree. His new role came as a surprise in Australia. After decades of importing North American academics and practitioners (with mixed results), this was a major shift in fortunes. In his essay for this book, the significance of this career move barely rates a mention. I pressed him on it.

Richard did not aim to go to North America. He was successful and comfortable in Perth with an off-campus city-based studio, good

resources, and access to policy makers and politicians, including the premier of Western Australia. His collaboration with Vladimir Sitta had allowed him to build a practice, continue to operate as an academic, and have ample opportunities to travel and lecture internationally. However, after Boomtown he felt that his urban planning project was done, and he was ready to move on. Whereas some might have chosen the path of comfort, shoring up their expertise and reputation, Richard by his own admission gets bored once a project has played out.

Penn presented the lure of an international platform along with its historical legacy of critical thought and leadership in landscape architecture. Moving countries meant a new academic culture—the public Australian university system, heavily influenced by the United Kingdom, is very different from a private Ivy League university such as Penn.12 In this new context, the pressure to “talk up” the program and the discipline more generally did not come naturally to Richard, who prefers to have influence through projects rather than rhetoric.

Penn offered resources to seed projects, and over time Richard has become more comfortable asking donors for funds to support initiatives to extend Penn’s influence and facilitate his own projects. In his first year he edited Transects: 100 Years of Landscape Architecture and Regional Planning at the School of Design of the University of Pennsylvania , and in another nod to legacy, in 2016 he curated the International Festival of Landscape Architecture “Not in My Backyard” in Canberra, celebrating the fiftieth year of the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects. At the same time he led the process of writing the New Landscape Declaration, a statement of the profession’s core values by the Landscape Architecture Foundation (LAF) in Washington DC.

Recognizing the absence of theoretically driven landscape journals and landscape critique more generally, in 2015 he established the LA+ Interdisciplinary Journal of Landscape Architecture with his partner, Tatum Hands. A trained lawyer and professional editor, Tatum is the Editor in Chief of LA+ and works closely with Richard on many of his publications. Inspired by Daidalos , which Richard read as student, over the past nine years, LA+ has explored themes as diverse as Wild, Pleasure, Creature, Tyranny, Simulation, Risk, and Interruption, and it is now considered central to disseminating landscape discourse internationally.

Relocating to Penn also meant engaging with the North American landscape agendas dominated by issues of resilience, climate change,

and now decarbonization. The establishment of the Ian L. McHarg Center for Urbanism and Ecology as a multidisciplinary research center has provided a major mechanism for Penn’s landscape program to focus their work. Marking the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of McHarg’s seminal work Design with Nature , the center was launched in 2019 with an international symposium, the publication Design with Nature Now , and a supporting exhibition. And in a final homage to Penn as his tenure as chair concludes, The Landscape Project (2022), coedited by Richard and Tatum, draws together the writings of his colleagues to offer a record of ideas which influence the contemporary project of landscape architecture.

Developed in collaboration with many, these highlighted projects are vehicles for documenting and disseminating other people’s voices and ideas. Instigating, editing, organizing, framing, hosting, curating—this is work that is taken for granted in the hierarchical academic model that rewards individual success. Richard has done plenty of it in his career. Many students, academics, researchers, and practitioners in Australia, North America, and from wider geographies have been provided opportunities by Richard, me included. Thank you.

A Question of Scale

The climate crisis has reinvigorated landscape architecture internationally. It has, though, been accompanied by two problematic tendencies: first, for the profession to spend considerable energy describing the crisis (as if it has gone unnoticed); and second, the declaration of landscape architecture’s unique position to address these issues. For example, the recent 2022 IFLA world congress in Korea featured a “motivating” film clip on a loop depicting landscape architecture with almost superhero characteristics. Stewardship on steroids.

Critical of landscape architecture climatic dogma, Richard entered the era of the Anthropocene through his preferred mode of the project. His intentions were not to find a solution but to work with design speculation to test landscape methods at the scale of the global and planetary. As he comments, while every discipline is concerned with climate change, “design is the one thing the landscape architect can bring to the table that others cannot.” 13 His first project in this arena, the “Atlas for the End of the World,” used mapping, supported by statistics, to highlight the conflict between global urban development and biodiversity. The scale then shifts to ground the project in the cultural, ecological, and political specifics

of the world’s “biodiversity hotspot” cities where the surrounding unique biodiversity is critically threatened by urbanization.

The “World Park” project builds on the Atlas. Global-scale mappings document three walking trails, which transect nations and connect biodiversity hotspots and habitats along the way. Through the cultural practice of walking, these trails aim to encourage humans to participate in the restoration of landscape connectivity, along with reversing the historical role of national parks, which separated culture from a pristine wilderness. To address the challenges of climate change, Richard states, “requires the rationality of the planner, the cunning of the politician, and the imagination of the artist.” 14 The World Park project reflects these attributes, working between the two poles of the allegorical and the instrumental. It is a simply communicated yet complex idea which offers a focus to mobilize funds (hopefully obtained from a Musk, Bezos, Gates, or a Winfrey), and it has caught the attention of UNESCO, which is currently exploring its possibilities.

Richard warns that some people might view this approach as an example of a “neo-colonial megalomania,” explaining in his writings how mega-eco projects differ from megaprojects.15 Coming back to his intent to explore the global and planetary scales, I suggest that it is not at the geographic or landscape scale that the World Park project is vulnerable, but at the scale of economic, cultural, and political disparity . Like Richard, I want to believe in the power of a big idea to address climatic issues. He clearly sees the potential of the mega-eco project underpinned by landscape architectural thinking as a major way for the discipline to address the loss of biodiversity and global warming. Here is where my earlier reference to “a Bob Geldof presence” kicks in—partly in recognition of Richard’s charismatic sensibility 16 but mainly for their shared ambition to mobilize at scale for a greater social and ecological outcome.17 But for me, there are just too many assumptions of commonality underpinning the World Park project. Most of the examples used to support a mega-eco approach involve one nation, or at most eleven, in the case of the Great Green Wall.18 Scaling a project to encompass fifty-five nations is where the fun really begins.

This highlights the difficulty of landscape architecture in comparison to architecture. Our work often fails to materialize because forces outside of our control must align. The more ambitious the project, the more alignment required. I am writing this essay from Malaysia, where I have been able to witness how designer Ng Sek San has

exploited the cracks of an imperfect political system to achieve the Kebun Kebun Bangsar project—an extraordinary linear community garden within a power line easement in the heart of Kuala Lumpur. Met with considerable resistance, Sek San has persisted and aims for the project to grow into a two-kilometer corridor linking the botanic gardens with the inner city. This is not an argument about “bottom-up” versus “top-down” practice, but rather recognition of the complexity of scale when it comes to negotiating change. Richard and Sek San share a commitment to using projects rather than platitudes to address social, climatic, and economic issues. Maybe only part of the World Park will be realized. Would that be a terrible outcome?

Work, Work, Work

By his own admission, landscape architecture frustrates Richard. A creative and intellectual indifference permeates the discipline—from an uncritical acceptance of genius loci (the site) as the source of all ideas, to the moral righteousness currently shaping the response to the climate crisis. In a particularly bruising observation, he comments that “by shifting the problems of culture onto the innocence of nature, works of landscape architecture effectively inoculate themselves from the sort of critique that would apply to any other aesthetic practice.” 19 Like the achievements of his great mate Peter England in theater set design, Richard could have left landscape architecture and had success in any number of creative fields. But he elected to stay within. Through projects, exhibitions, writing, and lectures, alongside running landscape architecture programs, research centers, journals, and competitions, Richard has challenged landscape architecture to deepen its engagement as a design discipline.

Frustration is a great motivator. Throughout his career, Richard has been tactical in exploiting opportunities and making them for others. His power of communication and charisma has certainly played a part. As this book documents, he has amassed an extraordinary body of work—some built, many remaining speculative, some acclaimed, others challenged. The idea of the project—which he considers the fundamental way to make sense of and engage with the world—drives this productivity. However, not the project as defined by a site or a brief, but a project as a focus to explore ideas about something— national identity, trauma, loss, the suburb, or the Anthropocene, to name just a few. It is a record of work that challenges the discipline to be braver and smarter, to be experimental and creative, and at times to fail. This is what it means to work between art and instrumentality.

END NOTES

1. The title references an iconic song by The Triffids, who emerged from Perth in the late 1970s. Lead singer David McComb is acknowledged as one of the rare songwriters to capture the sense of isolation and expansiveness of the Australian landscape. It’s also a bit of an anthem for expatriate Australians of a certain generation. Have a listen.

2. Don’t for a minute think that Richard’s reflections herein on his studies at UNSW are exaggerated. Studying a few years later than Richard, I can confirm, among other things, that data punch coding was soul destroying.

3. Hold this thought—this reference becomes more evident towards the end of this essay.

4. Richard Weller, “Inside Room 4.1.3,” Room 4.1.3: Innovations in Landscape Architecture (Univ. of Pennsylvania Press, 2005), 3.

5. Ibid.

6. See Matthew Rimmer, “The Garden of Australian Dreams: The Moral Rights of Landscape Architects,” in Fiona Macmillan & Kathy Bowery (eds), New Directions in Copyright Law: Vol. 3 (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2006), 134–70.

7. https://aiatsis.gov.au/ngurra

8. In 1998, Richard’s work was recognized as such as a finalist in the Seppelt Contemporary Art Award, see https://www.mca.com.au/artists-works/exhibitions/seppelt-contemporary-artaward-1998/.

9. Richard Weller, “Landscape (Sub)Urbanism in Theory and Practice,” Landscape Journal 27, no. 2 (2008): 262.

10. Interview with Richard Weller (September 26, 2022).

11. Corner completed a master’s degree in landscape architecture and an urban design certificate from the University of Pennsylvania in 1986, while McHarg earned a B.L.A. in 1949, an M.L.A. in 1950, and a master’s degree in city planning in 1951 from Harvard University.

12. Contemporary academic leadership requires a challenging set of skills and a tolerance for bureaucracy. The ability to balance budgets and attract funding, maintain a career trajectory without being an absent leader, remain an active and engaged teacher, liaise with other disciplines, operate beyond self-interest, manage academic staff, support a new generation of academics, and respond to an increasingly demanding and anxious student body are just some of the demands. And most people are not up to the task. While always chasing big ideas, Richard seems also able to keep the day-to-day demands ticking over. This is a rare skill.

13. Richard Weller, “Afterword,” in The Landscape Project , eds. Richard J. Weller & Tatum L. Hands, (AR+D Publishing, 2022).

14. See Richard Weller’s essay herein.

15. Rob Levinthal & Richard Weller, “The Age of the Mega-Eco Project,” Landscape Architecture Magazine (in press).

16. In 2009 Richard was featured on the cover of the Sunday Times Magazine . He was photographed with bare feet wearing a white suit and holding a Rubik’s cube superimposed with urban scenes. Without question this was a design rock star moment.

17. Lead singer of the Irish band the Boomtown Rats, Geldof is also recognized for his activism in advocating for equitable and sustainable development in Africa.

18. The problematic top-down approach initially applied in the Great Green Wall project is well documented.

19. Richard Weller, “The Innocent Landscape,” The Architecture Symposium: A Broader Landscape , National Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney (November 18, 2022).

View inside the labyrinth of “The Women’s Rooms,” where rooms are serviced by a costumery to encourage visitors to use the park for masquerade and live-action roleplay [124].

population

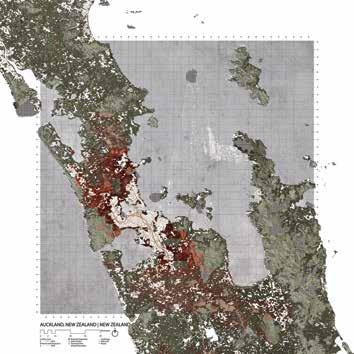

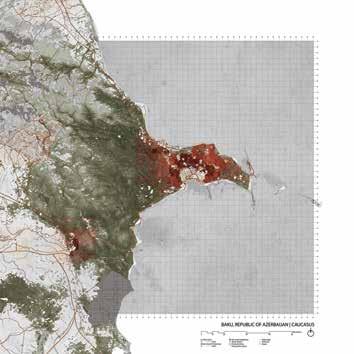

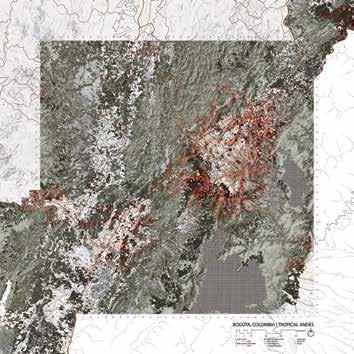

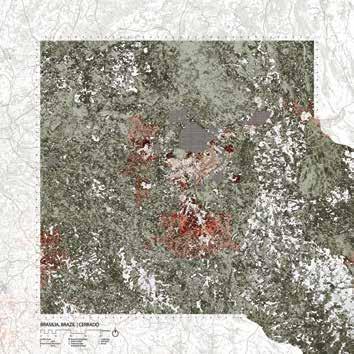

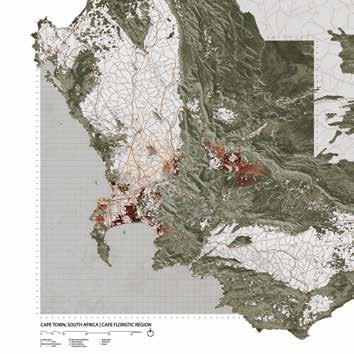

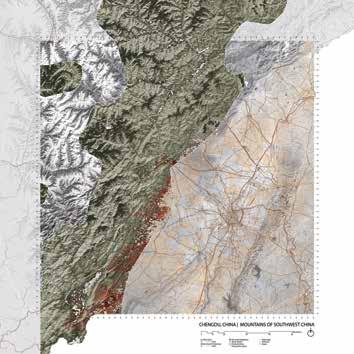

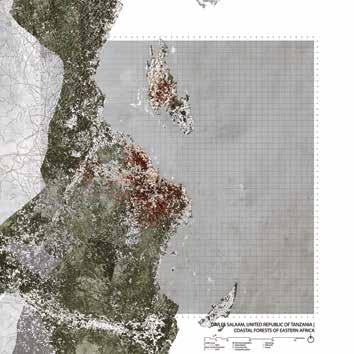

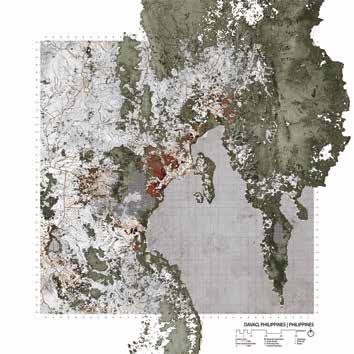

Mapping from “The Hotspots Cities Project” showing the fastest-growing cities in the world’s biodiversity hotspots. These maps show (in red) areas of imminent conflict between urban growth projected to 2050 and endangered species [149].

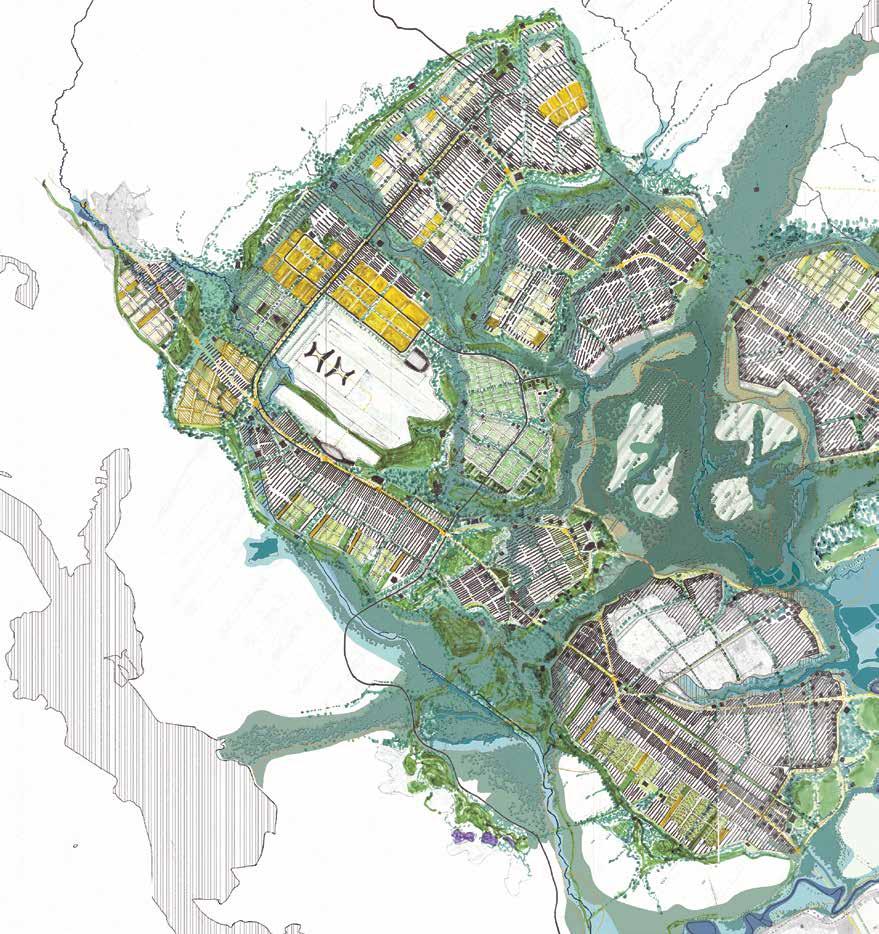

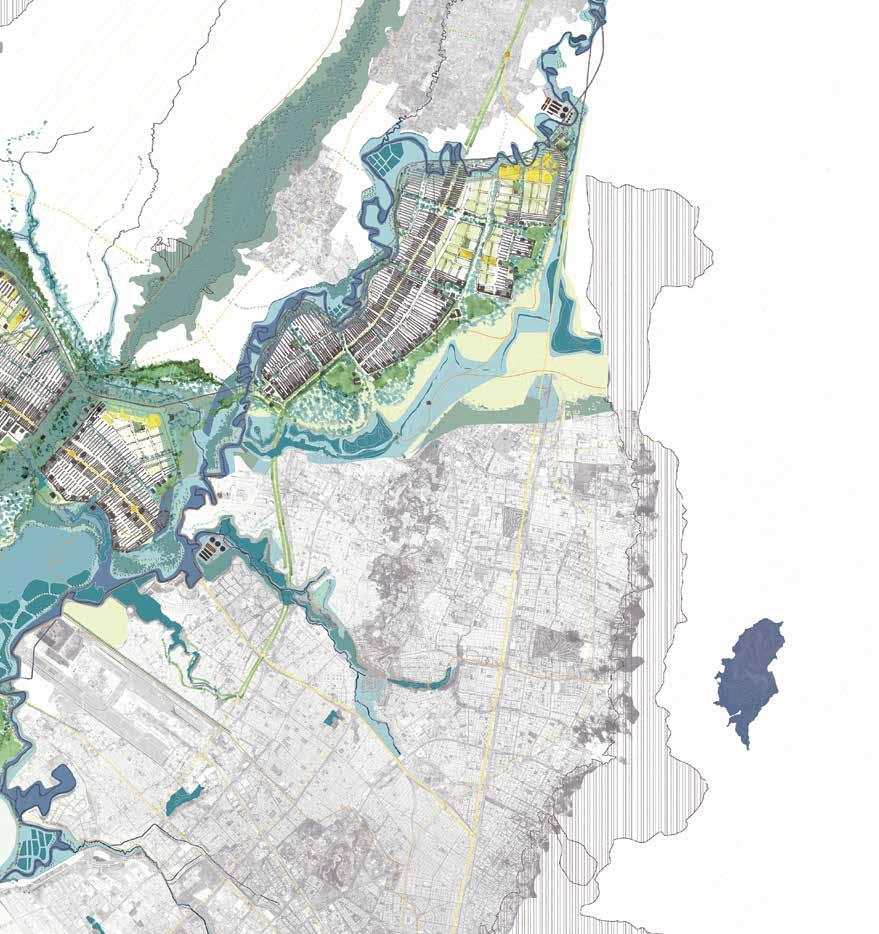

master plan

for

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Until now I have never stopped work to really acknowledge the importance of the friends, family, and colleagues who have variously enabled and contributed to my career. I’m grateful to my parents, Robin and Sam, for a childhood full of freedom and imagination. Contrary to the negative stereotype, suburbia for me was full of eccentric characters conducting backyard experiments. I was also fortunate to have always had wildly intelligent and creative friends. Chris and Steve Packer, Jay Balbi, Peter Beasley, and the Bossell family loom large in my memory. Academically, I was lucky to study under two inspirational design professors, Helen Armstrong and Craig Burton, and philosophy professor Graham Pont. Later, academic colleagues such as Simon Anderson, Geoffrey London, Patrick Beale, Clarissa Ball, Leon van Schaik, John Dixon Hunt, Laurie Olin, Marilyn Jordan Taylor, and Fritz Steiner have all been supportive and generous at different times. Professionally, I was fortunate to have been given significant opportunities by Luqman Keale, Jan Wehburg and Cornelia Müller, and architects Ashton Raggatt McDougall. Thank you also to the Landscape Architecture Foundation and the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects for involving me in the curation of legacy events. Over the years I have had talented research assistants and collaborators such as Lizzie Burt, Daniel Firns, Karl Kullmann, Julian Bolleter, Tom Griffiths, Mike Rowlands, Donna Broun, Claire Hoch, Shuo Yan, Chieh Huang, Tone Chu, Zuzanna Drozdz, Nanxi Dong, Oliver Atwood, Madeleine Ghillany-Lehar, Alice Bell, Shannon Rafferty, Elliot Bullen, Emily Bunker, Jiacheng Chen, and Rob Levinthal. Of this group I especially want to acknowledge Donna Broun whose research underpinned the Boomtown 2050 project and Julian Bolleter who partnered with me on the Made in Australia project. I want to also thank Jiachen Sun, Andreina Sojo, Yining Zhu, and Elliot Bullen for helping me pull together the manuscript and refine the images and layout for this book. I am also particularly thankful that Jillian Walliss and Dirk Sijmons—two landscape architects whom I admire—agreed to contribute essays.

Finally, I would especially like to single out four people. First, Vladimir Sitta, a master craftsman and relentless experimentalist from Brno in Czech, who has served as a co-conspirator pretty much from the beginning. On all the projects we did together over many years, while I could think a project to life, it was Vladimir who could refine it and build it. Second, I raise a very big glass to my best mate, the landscape architect and set designer Peter England with whom I’ve shared many sleepless nights arguing about art and earth spirits. Third, James Corner, whose writings in the early 1990s confirmed my own ramblings and who entrusted me to succeed him as Chair of Landscape Architecture at Penn. Finally, and above all, I thank my partner Tatum Hands who has not only put up with my constant over-indulgence in all this work, but contributed to it in myriad ways.