111 Literary Places

All Hallows by the Tower

Samuel Pepys records the Great Fire of London | 10

Arnold Bennett’s Steps

A novelist’s ascent to fame | 12

Athenaeum Club

Where two great writers reconciled | 14

Bank of England

Where The Wind in the Willows first stirred | 16

Bedford Park

G. K. Chesterton’s anarchists in arcadia | 18

Bertrand Russell’s Home

Nobel Prize winner’s childhood at Pembroke Lodge | 20

The British Library

George the III’s Library fit for a king | 22

Brompton Cemetery

Where Beatrix Potter met Peter Rabbet | 24

Browning Room

The Secret Wedding of Barrett and Browning | 26

Brown’s Hotel

Home from Home | 28

Buck’s Club

Inspiration for P. G. Wodehouse | 30

Cadogan Hotel

The humiliation of being Oscar | 32

Cambridge Circus

Where spies came out from the cold | 34

Campden Grove

James Joyce ties the knot | 36

Canonbury Tower

Oliver Goldsmith flees debtors | 38

Carlyle’s House

The French Revolution written here | 40

Cecil Court

Arthur Ransome’s early workplace | 42

The Charing Cross Hotel

Edith Wharton’s passion changes her life | 44

Charles Dickens Museum

Portrait of the writer as a young man | 46

Christ Church

Jack London in the Abyss | 48

Clapham Common

Graham Greene’s art imitated his life | 50

Cloth Fair

John Betjeman’s love nest | 52

C. L. R. James’ Last Home

The cricketing radical | 54

Cornhill

A door in the Square Mile tells a Brontë story | 56

Covent Garden

Johnson meets Boswell, and a great book is born | 58

Daniel Defoe’s Tombstone

A long journey to its present home | 60

Dean Street

Marx’s love life above a London restaurant | 62

Down House

Where Darwin explained our origins | 64

Dr Dee’s Library

The ‘lost’ library in an unusual place | 66

Farm Street Church

Brideshead had its origins here | 68

Flemings Hotel

Miss Marple’s London holiday | 70

Freud Meets Dalí

Meeting of an unlikely couple | 72

Gower Street

Ottoline Morrell entertains the literati | 74

Great Russell Street

A place of contrasting styles and stylists | 76

Grey Court

Cardinal Newman’s happy childhood | 78

Guildhall

Home of the Booker prize | 80

Hazlitt’s

Where William’s ‘happy’ life came to an end | 82

Henrietta Street

Rallying cry for the Left | 84

Bertrand Russell’s Home

Nobel Prize winner’s childhood at Pembroke Lodge

Built as a mole-catcher’s lodge in around 1774, Pembroke Lodge is now a tearoom, and a wedding and banqueting venue. Set in 11 acres within Richmond Park, the York stone path, green lawns, manicured flower beds and handsome design betray its aristocratic past. In 1847 it was given by Queen Victoria to her Whig prime minister Lord John (later Earl) Russell. And in 1874, a two-year-old Bertrand Russell and his three-year-old brother Frank came here to live in the care of their grandparents, having been orphaned by the death of their parents, Lord and Lady Amberley.

Lord Russell died when Bertie was six, but the countess lived until he was an adult. From her he developed a deep religious faith – although he was later one of the century’s great anti-religious polemicists – and a life-long love of English literature. Here, he imbibed an understanding of his family’s role in British political history, and resistance to authority and tyranny that sowed his later dissent.

Frank went to Winchester, but Bertie was tutored at home, with an education that fitted the future prime minister that his grandmother aspired he should become. He learned modern languages, economics, constitutional history, science, and mathematics. A lonely child, Russell wandered in the grounds and woods, delighting in the changing seasons. But when he was 11 there came the great turning point in his intellectual life: he was introduced to Euclidean geometry. To him it was ‘as dazzling as first love’.

Russell devoted his life to mathematics, philosophy, logic, and political activism. In 1950 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. In old age he reflected on the profound influence those long past years at Pembroke Lodge had had upon him: ‘I grew accustomed to wide horizons and to an unimpeded view of the sunset. I have never since been able to live happily without both.’

Address Pembroke Lodge, Richmond Park, SW10 5HX, +44 (0)208 940 8207, www.pembroke-lodge.co.uk | Getting there Overground or Underground to Richmond (District line) | Hours Daily 10am – 5pm | Tip You’re in one of London’s most extensive and attractive parks – look out for deer while you’re there! 630 Red and Fallow deer have roamed freely here since 1637. They are wild, though, so keep 50 metres’ distance!

Brompton Cemetery

Where Beatrix Potter met Peter Rabbet

As a child Beatrix Potter would wander along the leafy paths of Brompton Cemetery near her home at 2 Bolton Gardens in prosperous South Kensington, where she had been born in 1886. There she saw the gravestones of Peter Rabbet [sic], Jeremiah Fisher, Susannah Nutkins, Mr Tod, Mr Brock, and Mr McGregor. The discovery of this connection only became possible when the 250,000 recorded burials in the cemetery, opened in 1840, were computerised. It’s also possible that Potter knew a real Mr Nutkins – a butcher in nearby Gloucester Road.

Beatrix was born into a wealthy, Unitarian, middle class family. Both parents were the beneficiaries of Lancashire cotton fortunes, and neither had any cause to work, although Rupert Potter, a qualified barrister, did so until inheriting his wealth in 1883. Beatrix said that she could not remember a time when she did not try to invent pictures of a fairyland of wildflowers, animals, mosses and woods. She and her younger brother Bertram collected animals, beetles, dead birds, frogs and hedgehogs on which they ‘experimented’. From this grew Beatrice’s ‘picture letters’, often about her later familiar characters, the first sent to the son of her former governess.

When two publishers brought out some of her pictures as cards, she turned for advice to a family friend, Canon Hardwicke Rawnsley, an author and co-founder of the National Trust, about publishing a book. Being rejected by several publishers, she privately published The Tale of Peter Rabbit in 1901, her first step to transforming her animal characters into a series of best-selling books. As a result, Frederick Warne, publisher of children’s titles, offered to bring out the book if the drawings were in colour. The book appeared in 1902. She then published a book a year until 1913, and then almost as frequently for the next 29 years until her death, aged 77, in 1943.

Address Fulham Road, SW10 9UG | Getting there Underground (District line) or Overground to West Brompton, or Earl’s Court (District, Circle, and Piccadilly lines) | Hours Daily 7am – 6pm | Tip Fulham Place on Bishop’s Avenue is a short walk away. Once home of the bishops of London, visitors can take a tour to enjoy the glories of the palace and the magnificent 13-acre walled garden.

Charles Dickens Museum

Portrait of the writer as a young man

What happened to Margaret Gillies’ portrait of 31-year-old Charles Dickens after it was last seen in 1886 is a mystery. So, too, is how it came to turn up again in 2017 – in South Africa. How did it get there?

It’s likely that Dickens and the Scottish painter came to know one another through a shared interest in social reform. In 1843, Dickens wrote to Gillies and told her that he would turn up for a sitting the next day, 24 October, nearly two months before A Christmas Carol was published. The watercolour and gouache on ivory miniature was shown the following year at the Royal Academy. Nearly 40 years later, though, Gillies, wrote in a letter, held by the museum, that she could not account for the portrait, and had ‘lost sight of it’, which suggests unexplained loss. The only visual evidence of it was a simple black and white engraving. However, a house clearance in Pietermaritzburg revealed it in a box of trinkets. It was probably taken to South Africa by one of the sons of George Henry Lewes, lover of the novelist George Eliot (see ch. 100), when he emigrated there in the 1860s. The portrait, missing for 130 years, underwent extensive conservation, and is now in the museum after a fund-raising campaign.

The museum, situated in one of only three of Dickens’ homes still standing (the other two are not in London), was where the novelist lived with his wife, Catherine, and their then three children, from March 1837 to December 1839. While here, Dickens wrote Oliver Twist and Nicholas Nickleby, completed The Pickwick Papers, and worked on Barnaby Rudge. The house was mainly used as a boarding house when the family left. In 1923, the Dickens Fellowship purchased it, and it was opened to the public in 1925. Today the house is home to over 100,000 items comprising furniture, personal effects, paintings, prints, photographs, letters, manuscripts, and rare editions.

Getting there Underground to Russell Square (Piccadilly line) | Hours Wed – Sun 10am – 5pm | Tip The Foundling Museum was once part of the Foundling Hospital or orphanage, which encompassed Coram Fields, now in front of the building; it outlines the history of the orphanage in the context of children’s welfare at that time (www.foundlingmuseum.org.uk).

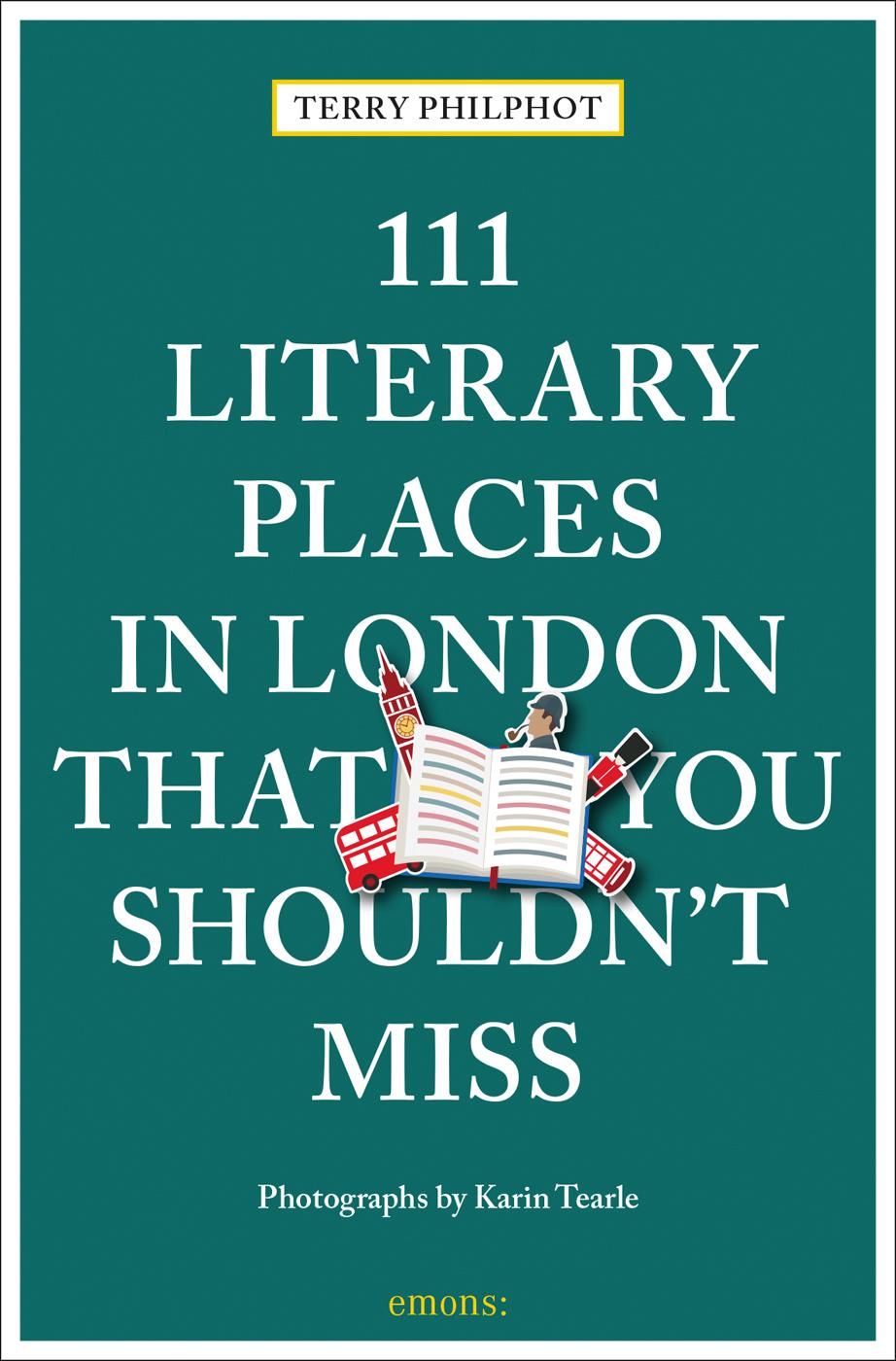

Dr Dee’s Library

The ‘lost’ library in an unusual place

The Royal College of Physicians is the oldest medical college in the UK, but perhaps not the obvious venue for a collection of antiquarian books. The college has been collecting since its foundation in 1518, and includes a first edition of Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales, and medical texts by Greek, Roman and Arab doctors.

However, perhaps the most usual and rarest part of the collection in the library is that of Doctor John Dee. Born only nine years after the college’s foundation, he was one of Tudor England’s most extraordinary figures – a polymath, with interests in almost all branches of learning. He was also an Elizabethan courtier (he was a astronomer to Elizabeth I), an adviser on several navigations of the New World, and also made many journeys to the Continent.

His creation and loss of one of the greatest private libraries of his time may be his most enduring achievement. He claimed to own 3,000 books and 1,000 manuscripts housed in his Thames-side home, far more than in the libraries of Oxford and Cambridge universities. They reflected his catholic interests: among them, natural history, music, astronomy, astrology, military history, mathematics, cryptography, ancient history, alchemy, and the world of angels. His scholarship was such that his many annotations, in elegant italic, have themselves been subject to academic study.

There are two accounts of how so much of Dee’s library was lost. He said that his brother-in-law, to whom he entrusted it while he went to Europe, ‘unduly sold it presently on my departure’. But it is also claimed that books were stolen by aggrieved former associates. He recovered only some of the collection. Much of what was unrecovered passed to other hands. Fortunately, much came to the Marquis of Dorchester, for on his death in 1680 (Dee had died 71 years before) it passed to the RCP, which has the largest holding of his printed books.

Address Royal College of Physicians, 11 St Andrews Place, Regent’s Park, NW1 4LE, +44 (0)203 075 1313, www.rcplondon.ac.uk | Getting there Underground to Regent’s Park (Bakerloo line) or Great Portland Street (Metropolitan, Circle and Hammersmith & City lines) | Hours Tue – Thu 9.30am – 4.30pm; appointments on +44 (0)203 075 1313 and via history@rcplondon.ac.uk | Tip Harley Street is a synonym for (private) medical practice and is itself an 18th- century street of handsome houses in varied design. There are few private houses here now. Doctors came in the mid-19th century and William Gladstone lived at No. 73.

Grey Court

Cardinal Newman’s happy childhood

Ham is now pleasantly situated on the western outskirts of London, but when John Henry Newman’s parents bought Grey Court (now Newman House) before he was born in 1801, it was deep in the English countryside. The Newmans had a London home in Bloomsbury, but it is perhaps appropriate that Grey Court is now part of the school from which it takes its name, for here Newman was happiest. This was so much so that he wrote: ‘When, at school, I dreamed of heaven, the scene was Ham.’ When he was 60, he said that he knew more about Grey Court ‘than any house I have been in since, and could pass examinations on it’.

When the family placed candles in their windows to mark the country’s victory at the Battle of Trafalgar, this may have inspired his hymn Lead, kindly light, written in 1833 when he was a young Anglican clergyman. But in 1864 he published Apologia Pro Vita Sua, his spiritual autobiography. This was a defence of his decision to resign from the Church of England in 1844, a prelude to his reception into the Catholic Church two years later. Created a cardinal in 1879, he had long been a major influential figure in British religious life: a leading figure, first in the Church of England’s AngloCatholic Oxford Movement, and then, in his new home, as a Catholic in the 19th century as a counterweight to the strong anti-Catholicism sentiment of his time. The book remains in print and is a spirited defence of the Church.

Newman was unusual, among clergy, in being both author and poet – his long prose poem, The Dream of Gerontius, was set to music by Edward Elgar. His Grammar of Assent makes the case for religious belief. His Idea of the University is credited with the British belief that higher education should produce generalists, not narrow specialists, and that non-vocational subjects can train the mind. Newman himself founded what is now University College, Dublin.

Address Ham Street, TW10 7HN | Getting there Train to Richmond, then bus 317 to Ham Street | Hours Viewable from outside only | Tip Less than a 15-minute walk away, Ham House and Garden is a striking 17th century Stuart House, with a unique collection of cabinets and artwork. The cherry garden is delightful, with original 17th century statues of Bacchus (www.nationaltrust.org.uk).

Henrietta Street

Rallying cry for the Left

Victor Gollancz started his eponymous publishing company in 1927 at 14 Henrietta Street in Covent Garden, and would go on to acquire authors such as Daphne du Maurier, Elizabeth Bowen and Kingsley Amis. In May 1936 he founded the Left Book Club, a subscription service, ‘to help in the terribly urgent struggle for world peace and against fascism’. The enterprise, established with the help Sir Stafford Cripps and John Strachey, two future Labour Cabinet ministers, was something of a movement: not only was there a broadly shared political outlook among members, but there were also 1,500 discussion groups allied around the books, and an annual rally. Subscribers were offered a book each month, and also received a newsletter, which engaged in discussion rather than simply being an advertising vehicle.

The books had distinctive coloured covers: orange for paperbacks, red for hardbacks. Authors included the Communist-leaning cleric Hewlett Johnson (with whom Gollancz fell out over the Nazi-Soviet Pact), Strachey and Cripps, the future prime minister Clement Attlee, poet Stephen Spender, and the writers Arthur Koestler and George Orwell, whose The Road to Wigan Pier was published with amendments: Gollancz was a very interventionist editor.

Membership reached 20,000 in the first year, and the following year peaked at 57,000. Numbers decreased, however, as Communists left when the club came out against the Nazi-Soviet Pact in 1939. Wartime paper rationing did nothing to help matters, and Gollancz published his last book in 1948. By that time the club had a big achievement under its belt, however: it is largely credited with the leftward political swing in the country that brought Labour to power in 1945.

When Gollancz suffered a stroke in 1966 his daughter Livia, an accomplished professional musician, ran the company until 1989, when it was sold to Houghton Mifflin.

Address 14 Henrietta Street, WC2E 8QG | Getting there Underground to Covent Garden (Piccadilly line) | Hours Viewable from outside 24 hours | Tip Charing Cross, five minutes’ walk away, is where Edward I erected a cross at the 12 resting places from Lincoln to Westminster for the funeral of Queen Eleanor of Castile in 1290. All mileage distances throughout Britain are measured from here.

Marx Memorial Library

More than a memorial to Marx

Two events in 1933 brought the Marx Memorial Library into being: the 50th anniversary of the death of Karl Marx, and the public burning of books by the Nazis in Berlin. But this handsome Grade IIlisted building has a far longer history than the library it now houses, or even of Marxism.

It was founded in 1738 as a Welsh charity school. The school moved out in 1772 to be succeeded by workshops when the building was divided, partly to become the home of the London Patriotic Society from 1872 until 1892. A radical printer took over, and the building returned to single occupancy. In 1826, the writer William Corbett made his speech against the Corn Laws on the green.

Many well-known writers and radicals are associated with the library: William Morris (see ch. 110) was an early benefactor, while Lenin had an office here (which can still be seen) when editing the revolutionary Russian-language newspaper The Spark from 1902 to 1903. This was printed on especially thin paper to enable it to be smuggled into Russia.

The library’s cultural and educational remit roams further than its name may suggest. Its library has 50,000 books, pamphlets and periodicals on matters from Marxism to the anti-apartheid struggle, the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 to the Poll Tax protests of the 1980s. Extensive archives relate to the International Brigade in the Spanish Civil War, and the print unions. There are 1,600 posters, and, in addition to lectures, online learning is also available. Over the years, the library –originally with the suffix ‘and Workers’ School’ – has expanded to fill the whole building. One treasure of the library is a mural – ‘The worker of the future clearing away the chaos of capitalism’ – painted in 1934 by the Communist Viscount Hastings, who studied under the Mexican artist Diego Rivera. It was discovered behind a bookcase.

Address 37a Clerkenwell Green, EC1R 0DU, +44 (0)207 253 1485, www.marx-memorial-library.org.uk | Getting there Overground or Underground to Farringdon (Circle, Hammersmith & City, and Metropolitan lines) | Hours Tours Mon at 12pm; reading room Tue – Thu 11am – 4pm, by appointment | Tip The Charterhouse in Charterhouse Square, EC1M 6AN is on an ancient monastic site. It has been a private mansion, a school, and is now a residential care home. Its long and diverse history is shown in its museum, for which tours are available (www.thecharterhouse.org).

Russell Square

Where T. S. Eliot, the poet, discovered poets

In what is now part of the University of London’s Birkbeck College’s School of Social Science, History and Philosophy, 25 Russell Square was once the offices of Faber & Faber, where T. S. Eliot worked as a publisher for 40 years. By the time he joined in 1925, the American, who later became a British citizen and was awarded the Order of Merit and the Nobel Prize for Literature, had published The Waste Land. He had taught at Harvard, arrived in England in 1914, made an unhappy first marriage to Vivienne Haigh-Wood, and tried teaching and banking. Virginia Woolf called him a ‘corpse’, with a ‘great yellow bronze mask for a face’. He must have been unaware of this, as a photograph of her was on his office mantelpiece. Despite Woolf’s description, he was said to light fire crackers in office waste bins to mark 4 July.

It was at Faber that he discovered a gift as a playwright and also converted to High Anglicanism. He enjoyed the conviviality of editorial life at Faber, which functioned like a club. He was responsible for publishing many modern poets, including Louis MacNeice, Stephen Spender, W. H. Auden, and Ted Hughes (see ch. 85). One visitor was his fellow poet George Barker, who remembered Eliot in 1939, as war clouds gathered over Europe, looking out of the window and saying in a tired voice, ‘We have so very little time...’.

It was also here that Eliot met Valerie Fletcher, his secretary, whom he would marry in 1957. Thirty-eight years his junior, she would become his editor and protective literary executor. Before then, often to escape his first marriage, he would sometimes sleep in a top-floor flat. Eventually committed to an asylum, Vivienne would sometimes turn up at the office unannounced. Eliot’s secretary would detain her, while he made his exit. Despite his increasing fame, Eliot remained with the company until he died in 1965.

Address 25 Russell Square, WC1B 5DT | Getting there Underground to Russell Square (Piccadilly line) | Hours Viewable from outside only | Tip In nearby Cartwright Gardens is a statue of the man after whom it is named: John Cartwright, the first English writer to openly maintain the independence of the USA, and who also supported universal suffrage, annual parliaments, and voting by ballot.

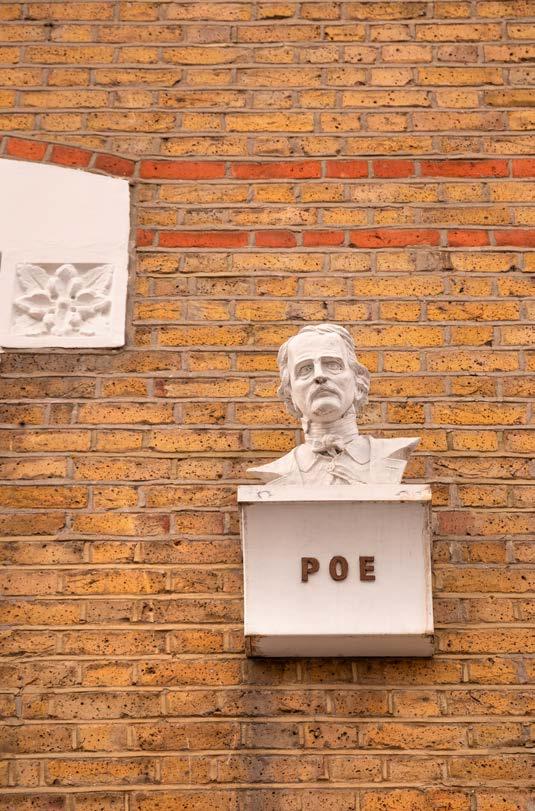

Stoke Newington Church Street

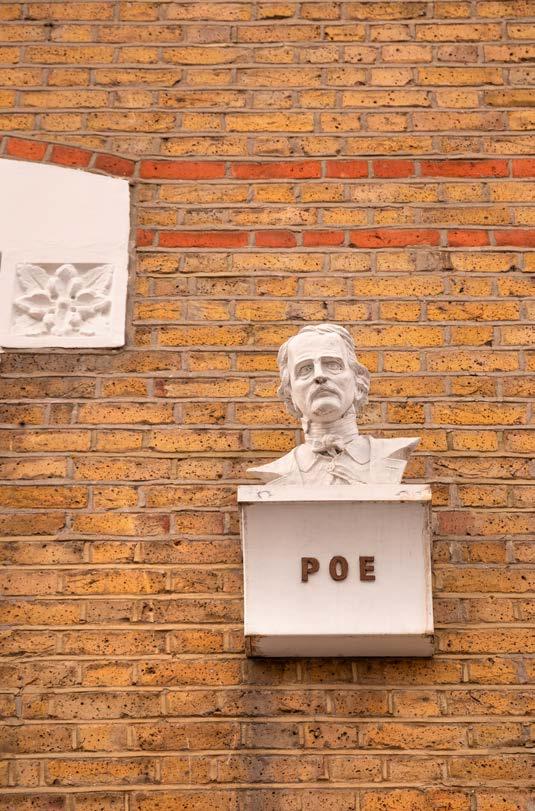

Where Edgar Allan Poe was educated

Edgar Allan Poe had experienced an unsettled childhood by the time he sailed to the UK from his native USA in 1815, along with his foster parents, John and Frances Allan. Poe was born in Boston, one of three children of American actor, David Poe, and English-born actress, Elizabeth Poe. His father abandoned the family in 1810, the year after Poe’s birth, and a year later his mother died of tuberculosis. John Allan was a successful merchant. The couple took him to the UK, and he spent a short time at school in Irvine, Ayrshire, from where Allan originated. Then, until summer 1817, he attended school in Chelsea. Poe enjoyed his school life, and had learned to read Latin by the age of nine. The ‘enchanted days’ came to an end two years later, however, when he was enrolled at the Manor School, Stoke Newington Church Street, where Daniel Defoe had once lived (see ch. 26). In an autobiographical short story, William Wilson, author of The Pit and the Pendulum and The Fall of the House of Usher, referred to the area as ‘a misty-looking village’. Under the oversight of the disciplinarian head teacher, Reverend John Bransby, Poe took dancing lessons and continued his French and Latin studies. Bransby regarded Poe as ‘intelligent, wayward and wilful’; his adoptive father praised him for being a good scholar. The family returned to the USA in 1820. Poe spent 10 months at the University of Virginia, took to journalism, served in the army, got himself discharged by purposely getting court-martialled, and wrote a number of books and short stories. Having achieved some prominence, he died at the age of 40 following a life of heavy drinking and chronic financial uncertainty – a period during which his wife also died. Today, a bust and a plaque on the building now on the site are reminders of Poe’s north London schooling.

Address 172 Stoke Newington Church Street, N16 7JL | Getting there Overground to Stoke Newington | Hours Unrestricted | Tip Green Lane is home to Clissold Park, one of the leastknown but most delightful London parks. Its 54 acres allow for cycling, privacy, relaxation, and places to eat, with a small zoo and a children’s playground (www.clissoldpark.com).

William Morris Gallery

Bringing beauty back to printing

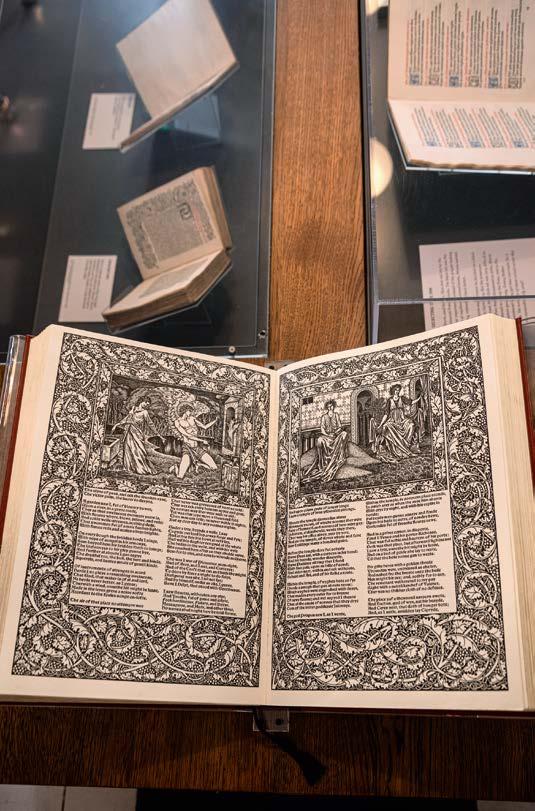

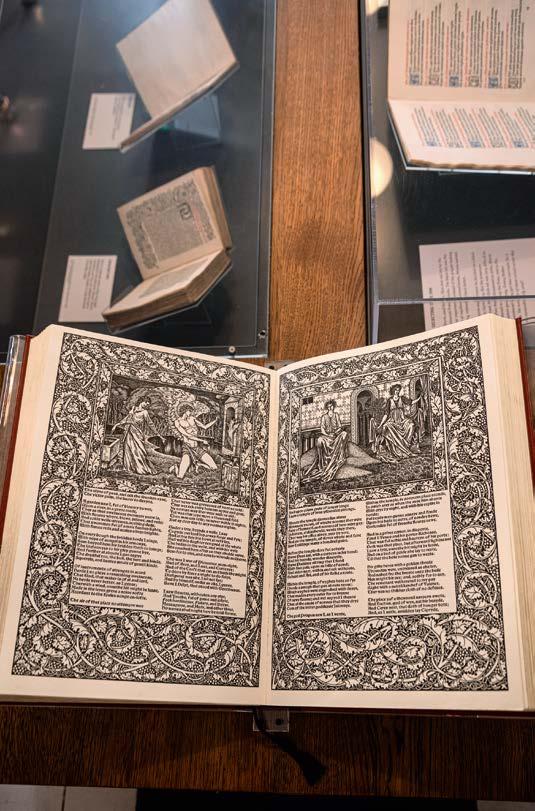

William Morris, writer, designer of fabrics and wallpapers, and pioneer socialist, was born here in 1838 in what was then a village. While the family moved to a grand house on the edge of Epping Forest when he was six, the area cast a spell over later life. In Morris’s News from Nowhere (1890), the 21st century Dick shows the time-traveller and narrator William Guest around the area after Guest’s 160-yearlong sleep and a mid 20th-century socialist revolution. He calls it, ‘A pretty place, too; a very jolly place, now that the trees have had time to grow again since the great clearing of houses in 1952.’

The gallery is full of books, items of furniture and memorabilia, but one of the most important items is a first edition of the Kelmscott Chaucer, published by Morris in 1896 on his own Kelmscott Press, founded in 1891. With 87 wood-cut illustrations by Edward BurneJones, the book is an example of Morris’ attempt to bring beauty to the printing of books. It exemplifies his wish that the press should revive the skills of hand printing, which mechanisation had destroyed, and restore the quality of 15th-century printing. The illustrations were engraved and printed in black, with shoulder and side titles. Some lines are in red, using Chaucer type, some titles in Morris’ Troy type, and the text type is from Venice of the 1470s. The whole was printed on Perch, a handmade, watermarked paper, using specially acquired ink from Germany.

Morris died in 1896, and the book was the last great achievement of his life. It combined his love of medieval literature and his socialist philosophy, which looked back to a time before the division of labour and mechanisation. Morris believed that these had destroyed personal fulfilment and the social function of meaningful work. There are few better illustrations of Morris’ social, political and creative outlook.

Address Lloyd Park, Forest Road, E17 4PP, +44 (0)207 496 4390, www.wmgallery.org.uk

Getting there Train or Underground to Walthamstow Central (Victoria line) | Hours Tue – Sun 10am – 5pm; entry is free | Tip Walthamstow Pumphouse Museum is a Grade IIlisted Victorian pumping station, opened by enthusiasts in 1997. There are displays of firefighting equipment, tube carriages and a modern railway (www.walthamstowpumphouse.org.uk).