Bold Action for Birds

American Bird Conservancy (ABC) takes bold action to conserve wild birds and their habitats throughout the Americas. Inspired by the wonder of birds, we achieve lasting results for the bird species most in need while also benefiting human communities, biodiversity, and the planet’s fragile climate. Our every action is underpinned by science, strengthened by partnerships, and rooted in the belief that diverse perspectives yield stronger results. Founded as a nonprofit organization in 1994, ABC remains committed to safeguarding birds for generations to come. Join us! Together, we can do more to ensure birds thrive.

Bird Conservation (ISSN: 3067-2228) is the member magazine of American Bird Conservancy and is published three times annually. Nonprofit postage paid at San Diego, California.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Bird Conservation, P.O. Box 249, The Plains, VA 20198. Send undeliverable copies to American Bird Conservancy, 8255 E. Main St., Suite D & E, Marshall, VA 20115. Return postage guaranteed.

Copyright 2025 American Bird Conservancy

Join Us

If you’re not already an ABC member, we invite you to join us. Members at any of our five levels of commitment receive a one-year subscription to Bird Conservation, access to members-only events and webinars, a choice of premiums, and other offers. Give now at abcbirds.org/membership or see contact details below.

Connect

Magazine feedback: We welcome letters to the editor and other feedback. Contact us at: magazine@abcbirds.org.

Membership or other inquiries: Contact us at American Bird Conservancy, P.O. Box 249, The Plains, VA 20198 | 540-253-5780 | info@abcbirds.org

Sign up to receive emails from ABC: abcbirds.org/email

Find and follow us on social media:

MAGAZINE STAFF

Vice President, Communications

and Marketing Clare Nielsen

Director of Communications

Jordan E. Rutter

Managing Editor Matt Mendenhall

Graphic Designer Maria de Lourdes Muñoz

Senior Writer/Editor Molly Toth

Director of Brand Strategy and Web Som Prasad

Science and Policy Consultants

Steve Holmer, Hardy Kern, Daniel Lebbin, George E. Wallace, David A. Wiedenfeld

Contributors Lindsay Adrean, William Blake, Jon Ching, Chris Farmer, Annie Hawkinson, Bennett Hennessey, Jeff Larkin, Sea McKeon, John C. Mittermeier, Jack Morrison, Veronica Padula, Garrett Rhyne, Christine Sheppard, Grant Sizemore, Adam Smith, Marcelo Tognelli, EJ Williams

COMMUNICATIONS AND MARKETING TEAM

Director of Marketing Lara Long

Multimedia Producer Erica Sánchez Vázquez

Media Relations Specialist Agatha Szczepaniak

Social Media Specialist Emily Williams

Digital Marketing Specialist Noah Kauffman

Digital Content Specialist Kathryn Stonich

ABC MANAGEMENT TEAM

President Michael J. Parr

Vice President of Advocacy and Threats

Programs Brian Brooks

Vice President of Development Erin Chen

Vice President of Finance Angela Modrick

Vice President of Operations Kacy Ray

Vice President of Policy Steve Holmer

Vice President of Threatened Species

Daniel Lebbin

Vice President of Together for Birds Naamal De Silva

Vice President of U.S. and Canada

Shawn Graff

Vice President and General Counsel

William “Bishop” Sheehan

Senior Conservation Scientist David Wiedenfeld

Director of International Programs Amy Upgren

Director of Migratory Bird Habitats in Latin America and the Caribbean Andrés Anchondo

Oceans and Islands Director Brad Keitt

Central Regional Director Jim Giocomo

Southeast Regional Director Jeff Raasch

Western Regional Director Maria Dolores Wesson

MEMBERSHIP TEAM

Membership Director Kelly Wood

Membership Coordinator Jenna Chenoweth

Database Quality Coordinator Jamie Harrelson

Office Manager Cindy Elkins

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Larry Selzer, Chair

Michael J. Parr, President

David Hartwell, Treasurer

Mike Doss

Jonathan Franzen

Maribel Guevara

Josh Lerner

Annie Novak

Ravi Potharlanka

Carl Safina

Amy Tan

Stephen Tan

Shoaib Tareen

Walter Vergara

Jessica Wilson

In Every Issue

4 Chirps

Comments on our summer issue.

5 From the Perch

Sharing the wonder of birds.

6 In Focus

Struggles of a tree-nesting seabird.

8 Bird Calls

Captive breeding successes, boost for a rare parrot, the Lesser Prairie-Chicken’s plight, a reprieve for a seabird haven, and more news.

14 The Stopover

Bottomland hardwood forests and the birds that rely on them.

38 Together for Birds

Bird conservation without boundaries.

40 Bird Hero

Christine Sheppard’s drive for safer buildings.

42 Action & Advocacy

How optimism and hope can lead to action.

43 Field Notes

How the Motus Wildlife Tracking System is changing our understanding of the movements of birds, bats, and insects — and creating improved conservation outcomes.

The Flute

Old bones from coastal Maine reveal ancient secrets of kinship between people and birds.

Keeping Watch

Introducing the first-ever ranking of U.S. and Canadian bird habitats by threat, spotlighting those most in need of conservation action.

Banding the tiniest birds.

44 The Science of Birds

How dynamic forests help birds, plus, news about seabirds.

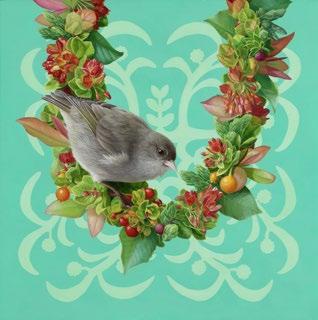

46 The Art of Birds

Creating emotional connections with art.

48 The Cache Books, discounts for ABC members, and a film about birders.

49 Flock Talk

Wear your ABC pride, readers’ photos, and more.

50 Field of View

How birds’ hidden lives connect people across continents.

Cover photo

Lewis’s Woodpecker at Lillooet, British Columbia by Ian Routley abcbirds.org/CoverBird

Bufflehead

Joshua Galicki

Chirps

What we’re hearing from ABC members and friends.

Generational Amnesia

For those of us who continue to read disturbing bird conservation reports of ongoing decline of common U.S. species and are old enough to distinctly recall large populations at the time we became fascinated with birds, we are sometimes stymied when nonbirders tell us, “There are lots of birds all around here!” The term raised by Laura Erickson in your summer issue (page 50), “generational amnesia,” clarifies this experience.

Recently, I was on an isolated island, when a friend of my daughter asked what I had seen on the beach. I proceeded to explain my sighting and photos of a pair of Piping Plovers that had three chicks the day prior and only two chicks that day. I was speechless at his response: “There’s lots of birds!” I attempted to explain the declining numbers of Piping Plovers, and he took no account of the implications.

While not a psychologist, I am aware that humans have two known psychological adaptations that contribute to this: change blindness and habituation. In change blindness, we are too distracted by more important needs around us to notice ongoing subtle changes, especially ones that don’t affect us personally at that time. In habituation, we accept and adjust to slow changes in the environment as long as they don’t disturb us too deeply.

With that in mind, other than publicizing the depressing figures, how else does one compete with human nature that is incapable of recognizing the problem proposed to us when our observations of the environment around us do not support the existence of a problem? Until other continental U.S. birds are posted alongside photos of the Passenger Pigeon? — Ken L.

Readers Reflect on our Summer Issue

Your issue has outstanding content and photography throughout, with engaging and meticulous layout, variety of topics, approaches and pathways to action. I was most moved by Laura Erickson’s article “Remembering Riches Amid Tireless Hope” — feeling deeply and brought to tears by her blend of gratitude and loss. Its placement as the penultimate article, followed by “Our Legacy for Birds,” was brilliant. — Cindy F.

I found every article interesting, but was especially pleased by all the information on Latin American birds. I backpacked extensively throughout the Andes in the 1970s, but I wasn't a birder. I have to start all over again, but I’m 80! — Jean E. I was really taken by “Forming Kinship With Seabirds.” I used to work in outdoor education and as a National Park Service seasonal ranger. I always used stories. Stories are timeless and are a wonderful way to connect people to nature, wildlife,

and other people. I wish there was a way to read some of the stories the grant recipients collected. — Kate M.

From the editor: Good news, Kate! Each Together for Birds Storyteller will write a blog post, so watch abcbirds.org for those. And farther down the road, we’re planning to publish a Together for Birds book with stories on seabirds and kinship. And this issue features an essay from Storyteller Alice Hotopp.

Social Media Followers Mention the Magazine

I got mine! It’s beautiful! Thank you ABC for your dedication to protecting birds and the habitats they need. — Patricia P. I just got my first issue as a new member recently and was really impressed with the print quality. And I work at a publishing company, so that’s saying something — Beth A.

Let’s hear from you!

Share your thoughts about our magazine, emails, or online content at magazine@abcbirds.org

Please include your full name and location. Letters may be edited for length and clarity. (Note: Opinions expressed are those of the authors.)

Larry Master

A days-old Piping Plover at Milford Point, Connecticut.

Sharing the Wonder of Birds

Birds. Why birds? How do we get so caught up in them? I often wonder how I became so bird-obsessed. Why not planes, or bowling, or professional wrestling?

Well, I do think there is something primordially satisfying about a connection to nature that transcends the human realm. Being able to put a name to a bird, recognize its flight pattern, and know its age and where it is going creates a powerful connection to the planet that feels deeper and more authentic than collecting postage stamps or memorabilia (which are fun and I also do).

Modern life has become so detached from the natural world. So much of what we experience is via third parties — television, radio, or (now mostly) our phones. It is so refreshing to watch an Osprey diving for a fish or a waxwing grabbing berries.

I find the simple things bring me the most joy. Consider a warbler, for example: a tiny being without need for money, clothes, complications. Yet there is so much to the life of this bird — a vast round-trip migration, a struggle to survive against what seem like huge odds, and yet a steely will to fly thousands of miles basically alone across unfamiliar terrain. And with no safety net. These are some of the things that create a sense of wonder for me when I see a wild bird.

Bird people all have bird stories, and many of us have many of them. These stories help convey our wonder about birds to others and encourage and inspire a love of birds to spread through the larger community. Here’s a quick one. (I hope you will share yours with us, too.)

A few years ago, while birding at Galveston Island State Park in Texas, I hoped to glimpse a Black Rail, a species that is sometimes seen there. As I wandered around, I became aware of a Northern Mockingbird imitating the rail’s kiki-du song. Minutes later, I noticed another sound coming from the marsh some distance away — a real Black Rail was responding to the mockingbird! After a bit of a dig around, I eventually spotted the rail — having gotten an assist from the mockingbird. It felt as though the mockingbird and I had collaborated in an epic birding moment. A real moment of wonder for me.

Thank you for supporting ABC. I look forward to hearing your birding stories and hope to share those to spread the wonder of birds even further. Please use the QR code or link below!

Michael J. Parr President

What does “wonder” mean to you when it comes to birds and

Alan Murphy

Aaron Allred, Deborah Freeman (inset)

A young Marbled Murrelet rests in its nest nearly 200 feet above the ground in a Douglas fir tree in Washington’s Mount Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest. The photographer and his climbing partner discovered the nest inadvertently, took a few photos, and left the chick undisturbed. In the inset, an adult murrelet flies just above the ocean surface.

Struggles of a Tree-Nesting Seabird

Like virtually every other threatened or endangered bird species around the world, the Marbled Murrelet’s fortunes improve when it’s able to live in healthy habitat. And perhaps to a greater degree than most other conservationdependent species, the murrelet also benefits when people simply don’t litter.

This special seabird’s range extends from Alaska to California; in northern treeless areas, it nests on the ground, but in the rainforests of the Pacific Northwest, it flies inland as far as 55 miles to nest high in trees. This bird needs large, flat branches to serve as nest sites, which are generally only found on trees aged over 120 years. Extensive logging over the last centuryplus led to decades of decline, and oil spills in the ocean, where it spends the nonbreeding season, have further reduced its numbers. Ravens, jays, and crows have long been known as predators of eggs and chicks at murrelet nests. However, about a dozen years ago, conservationists realized that food and garbage left behind by picnickers and campers can attract those predators, artificially boost their numbers, and increase the risk of nest predation. In 2013, California launched the “Crumb Clean Campaign,” a program to promote camper education and better ways to dispose of waste. The program worked well, and in 2022, ABC brought it to recreation areas in Oregon; we continue to expand the cam-

paign in Oregon and expect to launch it in Washington state in 2026.

Lindsay Adrean, ABC’s Northwest Program Officer, leads public education efforts by working on videos and signs “to get the message out about how visitors can reduce negative effects on murrelets and other animals.”

Longer term, the best hope for increasing murrelet numbers is to allow trees to get bigger and older by maintaining protections of the Northwest Forest Plan, which are now

at risk from a proposed revision and legislation in Congress. “Marbled Murrelets nest in the tops of old-growth and mature trees, and essential to their recovery is the need to grow more of these big trees,” said Steve Holmer, ABC’s Vice President of Policy. “This is happening under the Northwest Forest Plan, with recent monitoring reports showing that the plan is working as predicted to restore the old-growth ecosystem. Unfortunately for the murrelets, it takes a long time to grow old-growth nesting trees, and it will take about 70 years from now for sufficient trees to become available across the Pacific Northwest to provide for the murrelet’s recovery.”

Acknowledgments

Thanks to The Volgenau Foundation, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, and the Oregon Wildlife Foundation for supporting ABC’s Crumb Clean Program.

Read more and enjoy a video about this species in our Bird Library. abcbirds.org/MAMU

abcbirds.org/NFP

Population: 240,000-280,000

IUCN Status: Endangered Trend: Decreasing

Habitat: Old-growth coniferous forests, rock crevices and cliffs, bays, inlets, fjords, and open ocean.

Other Names: Guillemot marbré (French), Alca marmoleada (Spanish)

Marbled Murrelet Brachyramphus marmoratus

New Successes for Captive Breeding

Captive breeding programs for two Critically Endangered bird species of South America recently produced hopeful results.

In Brazil, captive Blue-eyed Ground Doves hatched four chicks this summer at the bird sanctuary Parque das Aves in the southern state of Paraná. The species, which numbers only 11 birds in the wild and 10 in captivity,

was rediscovered in 2015 after going undetected for more than 70 years.

The parents of the captive-hatched doves hatched in human care in 2023 and 2024 after their eggs were removed from wild nests. In those cases, researchers took the first eggs of the season, and the wild adult doves soon laid new eggs in their nests. The 2025 hatchings mark

the first time captive birds of this species have bred.

“Knowing how to breed Blue-eyed Ground Doves in human care means we are much closer to securing a safe captive population, which will give us more time to thoroughly understand the protection needs for the birds in the wild,” said Bennett Hennessey, the Coordinator of ABC’s Brazil Conservation Program.

In Argentina, conservationists with ABC partner Aves Argentina released three young

Hooded Grebes into the wild in May — the first captive-released chicks for the species known for its elaborate breeding dance.

The grebe, which numbers 600–650 wild individuals, has been the focus of captive breeding efforts since 2013. Pairs typically lay two eggs but raise only one chick, so when eggs are abandoned, biologists retrieve and transport them in incubators for up to eight hours across rough terrain.

Hand-rearing at a biological station in Patagonia National Park led to the release this spring. While the team plans to raise and release more chicks during future breeding seasons, they are concerned about the wild population because no more than 20 young chicks have fledged from wild nests in the last six years.

“This means that the population is growing older, making the hand-rearing program more critical than ever,” said Kini Roesler, who works with the Aves Argentina team.

Acknowledgment

ABC thanks Patricia Davidson for supporting Blue-eyed Ground Dove recovery.

Parque das Aves (top left), Albert Aguiar (top right), Gonzalo Pardo (bottom right), Rob Jansen/Shutterstock (bottom left)

Hooded Grebe chick (right) and adult (left)

Blue-eyed Ground Dove chick (left) and adult (right)

Lost Birds Grants Open to Young Birders

The Search for Lost Birds, a global collaboration led by ABC, BirdLife International, and Re:wild, has teamed up with Ornis Birding Expeditions to invite talented young birders to lend their expertise to the effort to locate and document lost bird species.

Grant applications are open for birders ages 18 to 30 wishing to undertake a search of their own for one of the roughly 120 listed lost birds. Two grants of $5,000 are available to fund expeditions.

The opportunity is best suited for highly skilled birders with experience seeking out and finding difficult target species in unfamiliar countries or regions. Comfort with backpacking, a desire to connect across cultures and language barriers, and an insatiable drive to bird are key qualities sought in candidates. Those interested are asked to submit a detailed proposal by December 20, 2025, explaining how they intend to effectively and safely carry out the search

Rising Numbers for a Rare Parrot

A recent census conducted by long-time ABC partner Fundación Jocotoco in Ecuador counted a remarkable 4,073 Critically Endangered Lilacine Amazons — three times greater than the expected count and close

for their bird of choice. Successful applicants will be announced in January.

More than 30 bird species have been found since the Search for Lost Birds began in 2021, and several have been located during Ornis Birding Expeditions tours.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to The Constable Foundation and Kathleen Burger & Glen Gerada for supporting the Search for Lost Birds.

Learn more and apply at ornis-birding.com/grants

to four times the estimated total population just under a decade ago. The counts were conducted at known communal roosting sites, where members of this highly social species gather night

after night. Visual observations were bolstered by counts produced by machine-learning programs that analyzed video recordings from cameras placed at roosts, a technology that can be scaled and replicated for other monitoring efforts.

Deforestation and capture for the illegal cage bird trade brought the Lilacine Amazon, once considered a subspecies of the Red-lored Amazon, to a tipping point. The population’s already small range in western Ecuador is highly fragmented, and the species has experienced alarming declines

that justified its IUCN Red List status upgrade from Endangered to Critically Endangered in 2020.

Partnering with Jocotoco, ABC has played a vital role in the species’ conservation, including by supporting the establishment in 2019 of the 246-acre Las Balsas Reserve. The reserve is managed in collaboration with the local Las Balsas community and protects critical roosting sites where 91 percent of the Lilacine Amazon population gathers. The community also protects 24,710 acres of forest nearby that are important breeding and foraging sites for the parrots.

The recently rediscovered Bismarck Kingfisher of Papua New Guinea was found thanks in part to an ABC grant. After being caught, the bird was released to the wild.

A Lilacine Amazon in a natural nest cavity.

A Great Loss for the Lesser Prairie-Chicken

The beleaguered Lesser Prairie-Chicken, which has an estimated total population of 30,000, lost its best line of defense this summer when a federal judge in Texas

overturned the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s 2022 ruling to protect the iconic species of the southern Great Plains under the Endangered Species Act (ESA).

ABC Board Elects New Chair

In September, ABC’s Board of Directors elected Maribel Guevara as its next Chair. Guevara will take the reins in January from the current Chair, Larry Selzer, who has served since 2017.

Guevara, an ABC Board member since 2022, was raised in Ecuador and is the Director of the ECOador International Film Festival, the country’s first environmental film festival. She lives with her family in San Francisco.

“I am proud to be elected Chair of the Board at American Bird Conservancy, becoming the first

woman to serve in this position,” Guevara said. “This achievement underscores ABC’s progress in advancing diversity within conservation leadership.

“Since joining the Board in 2022, I have been extremely impressed by ABC’s impactful programs and by their dedicated staff and talented Board members. As Chair, I hope to be an ambassador for ABC throughout the hemisphere, to have the opportunity to meet more partners and donors, and to help the organization increase the pace and scale of their work.”

The 2022 decision classified the grouse’s population in eastern New Mexico and southwest Texas as Endangered, and the populations in Kansas, Oklahoma, and the northeast panhandle of Texas as Threatened. In the new ruling, brought about by a lawsuit filed by the petroleum and other industry interests, the judge threw out both listings.

It was the latest — and perhaps most consequential — threat to the bird’s survival. Policy riders attached to the U.S. House’s proposed Interior Appropriations bill would also weaken ESA protections and block attempts to expand critical habitat for the prairie-chicken.

While ABC and partners explore ways to reinstate vital protections for the Lesser Prairie-Chicken, please urge your senators and representatives to oppose H.R. 587 and any policy riders that would de-list the species or shrink its habitat. abcbirds.org/LEPC

Selzer, the President and CEO of The Conservation Fund, oversaw a significant expansion of ABC’s size and scope as Board Chair between 2017 and 2025. ABC grew from a few dozen staff to 144,

while our revenues more than doubled — enabling us to do much more to conserve birds and their habitats throughout the Americas. We’re very grateful for his leadership!

Maribel Guevara and Larry Selzer

Lesser Prairie-Chicken

Endangered Golden-backed Mountain Tanager Gains New Reserve

A newly declared conservation area in central Peru protects cloud forest and other habitats for nearly 300 bird species, including 15 that are endemic to the country. Among them is the Endangered Goldenbacked Mountain Tanager, a spectacular bird with a population of less than 2,500.

Nature & Culture International, an ABC partner, and the regional

government of Huánuco led the project to establish the San Pedro de Chonta Regional Conservation Area, which protects 128,220 acres — an area slightly smaller than Redwood National Park in California. Rainforest Trust and the Andes Amazon Fund supported the effort, and ABC took part through the Conserva Aves initiative, which also includes the National Audubon

Society, BirdLife International, Birds Canada, and RedLAC.

“We congratulate our partners on this incredible achievement,” said Annie Hawkinson, International Project Officer at ABC. “The San Pedro de Chonta Regional Conservation Area is the first area declared in Peru under the Conserva Aves initiative: an exciting milestone and a critical step toward safeguarding the habitat of species of conservation concern.”

Return Trip

An ‘Ekupu‘u (Laysan Finch) forages on Kuaihelani (Midway Atoll) in late July — a significant step in the bird’s conservation. The species was wiped out from the island due to rats eight decades ago, and this summer, after a long planning process, 100 finches were caught on neighboring Manawai (Pearl and Hermes Atoll) and released by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service staff and partners. ABC was one of more than a dozen agencies and nonprofits that contributed to the planning and reintroduction of the birds to the fields of Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge and Battle of Midway Memorial. All of the birds wear unique color bands, allowing biologists to monitor their survival and behavior in their new home.

Jesús

Golden-backed Mountain Tanager

The Lower Montane Yungas forest in Peru is part of a new conservation area.

An ‘Ekupu‘u shortly after being released on its new island home this summer.

A Pacific Seabird Haven is Safe, for Now

Johnston Atoll, a former military testing site turned national wildlife refuge in the Pacific Ocean, is home for more than 1.5 million nesting seabirds. In the two decades since the U.S. military left the atoll, Johnston has had damaging invasive ants removed and been restored to support abundant biodiversity. Fourteen species, including half the world’s

Koaʻeʻula (Red-tailed Tropicbird) population, nest on the atoll, the only land for hundreds of miles, and the only land some birds will ever see.

ABC was among the first organizations to voice concern about the potential threat to seabirds when, earlier this year, the U.S. Department of the Air Force issued a notice proposing the construc-

Forest Purchase Helps Kites

In July, The Conservation Fund purchased more than 8,000 acres of forests near Carvers Bay, South Carolina, just southwest of Myrtle Beach. The land includes working forests, winding streams, and crucial habitat for the Swallow-tailed Kite, which is endangered in the Palmetto State.

Working forests — lands managed for timber produc-

tion — have helped ensure the kite’s survival and gradual increase in numbers. Forest loss, the draining of bottomland forests, and illegal hunting brought the bird’s population to dangerously low numbers by the early 20th century, reducing its breeding range from 21 states to just a handful in the Southeast, including South Carolina. Sustainably

tion and operation of two SpaceX commercial rocket pads on the atoll. The proposal put the future of the critical nesting habitat in question.

ABC requested that the Air Force prepare an Environmental Impact Statement to provide a full picture of the proposed project’s potential hazards. ABC also met proactively with SpaceX, offering to

assist in finding an alternative site for the project.

Late this summer, following concerns raised by ABC and others, the Air Force suspended its plans, leaving Johnston Atoll to the birds, for now. ABC is continuing to monitor the situation, including a new Executive Order that would exempt rocket launches from environmental review.

managed forests like Carvers Bay provide a mosaic of forest conditions that meet the needs of kites for nesting, roosting, foraging, and socializing.

“ABC has been active for a long while in the Carvers Bay Forest area, and we know it’s important for kites,” said Emily Jo Williams, ABC’s Southeast Director of Sustainable Forest Partnerships. “This is where we worked with partners, including Avian Research and Conservation Institute, to trap and equip four Swallow-tailed Kites with transmitters — providing us with vital information about their migratory routes and conservation needs.

Acknowledgments

“We are thrilled that The Conservation Fund has stepped up to protect this important working forest landscape. It’s critical to successful nesting by the kites and a host of other migratory birds, including Prothonotary and Prairie Warblers, Indigo and Painted Buntings, Acadian Flycatchers, and Yellow-billed Cuckoos.”

In the next four years, The Conservation Fund intends to work with the state’s Forestry Commission to permanently protect the special landscape by establishing a new state forest.

ABC is grateful to International Paper and the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation for supporting our work with Swallow-tailed Kites.

Swallow-tailed Kite

A Win for Hawai‘i’s Native Wildlife

The fragile ecosystem and native birds of Hawai‘i Island will benefit from a new law that prohibits feeding feral and stray animals — including cats, pigs, goats, and chickens — on properties owned or operated by the County of Hawai‘i. It takes effect on January 1.

ABC and partners, along with residents and cultural leaders, advocated for the Hawai‘i County ordinance. It protects county parks, beaches, and other public places where populations of introduced species have been concentrated and maintained by the availability of food offered by people. Cutting off these food sources is a critical step toward reducing the feral populations that have a devastating impact on birds and their habitats. Invasive species and habitat loss are

the primary drivers of the decline of the native manu (birds) of Hawai‘i.

The Hawai‘i Island ordinance builds on a similar action taken by the Kaua‘i County Council that took effect in 2023. The Kaua‘i ordinance, strongly supported by ABC and partners, bans cat feeding on all county property and prohibits cat abandonment across the island. Recently, ABC has also advocated for state laws that effectively manage cats throughout Hawai‘i, including by requiring that all pet cats be sterilized (with exception for registered breeders) and establishing liabilities for damages caused by a person’s cat. Grant Sizemore, ABC’s Director of Invasive Species Programs, has confirmed ABC will continue to collaborate with our local partners

and push for statewide cat legislation again in 2026.

Across the United States, outdoor cats kill approximately 2.4 billion birds each year, and cats have contributed to the extinction of 63 species, including 40 bird species, globally. Feral cats introduced to islands take an exceptionally high toll, which Hawaiian birds can scarcely afford. Hawai‘i is already the bird extinction capital of the world and saw eight of its native species declared extinct in 2023.

The need for further action became apparent within weeks of the signing of the Hawaiʻi County law.

In mid-September, André Raine, Science Director for ABC partner Archipelago Research and Conservation, discovered three mass kills on Kaua‘i of ʻUaʻu kani (Wedge-tailed Shearwater) totalling at least 180 birds.

Most were killed by cats and dogs, and Raine said such incidents “happen on an almost annual basis and at seabird colonies all over the island.”

Outdoor cats also spread toxoplasmosis — a parasitic disease transmitted by cats that can infect any bird or mammal, including domestic animals and humans. Toxoplasmosis is the chief disease threat to Endangered Īlio holo i ka uaua (Hawaiian monk seals) and has been found to harm a wide variety of other Hawaiian wildlife, including Nēnē (Hawaiian Goose), ʻAlalā (Hawaiian Crow), and spinner dolphins. Research in recent years has found high levels of environmental contamination in Hawai‘i with this parasite, all of which originate from cats on the landscape.

The Nēnē is vulnerable to predation by cats and to infection of a parasitic disease they spread.

The Endangered Īlio holo i ka uaua (Hawaiian monk seal) is threatened by toxoplasmosis, a parasite spread by cats.

Clark (top),

The Stopover

Lifelines for Vital Forests

The bottomland hardwood forests of the southeastern United States are places where rivers linger and the roots of giant bald cypresses, oaks, and other trees drink deep. Birds abound, including species such as the Prothonotary, Yellow-throated, and Kentucky Warblers, Louisiana Waterthrush, Red-headed Woodpecker, Wood Duck, and Acadian Flycatcher. Of course, the presence of cottonmouths, black bears, and alligators requires that we respect these flooded green cathedrals as places where the wild dominates.

But make no mistake: Today’s forests in the region suggest only a pass-

ing resemblance to their forebearers of the past. Uncontrolled logging and clearing for agriculture in the 19th and early 20th centuries slashed the original forests by about 80 percent. That’s one reason why ABC’s new Habitats WatchList considers the bottomland hardwood forest one of the most threatened habitats in the U.S. and Canada. (Read more about the WatchList on page 32.)

Several public lands throughout the South — including the 36,500-acre Bogue Chitto National Wildlife Refuge, pictured above — preserve important remnants of these forests. (Pro tip:

They’re often great places to bird!)

The best news for the forests and their treasured wildlife is that land managers and private landowners actively work to bring the habitats back. One vital organization in this effort is the Lower Mississippi Valley Joint Venture, a public/private conservation partnership that includes ABC. In the 1990s, it found that a mere 6.45 million acres of forest remained within the Lower Mississippi River Valley, often in small and scattered sites. Within 20 years, the partnership had already restored over 1 million more forested acres

in the valley, through land protections, conservation easements, reforestation on private lands, and conversion of agricultural fields into forest on state and federal lands. Beneficiaries include many beloved species, including the Swainson’s and Hooded Warblers and the iconic Swallow-tailed Kite.

Enjoy an ABC webinar about how working forests help birds in the southeastern U.S. abcbirds.org/TreesAtWork

A boardwalk winds through a seasonally flooded bottomland hardwood forest in Louisiana’s Bogue Chitto National Wildlife Refuge.

Species of concern in the region include the Prothonotary Warbler and Red-headed Woodpecker.

Kaleb Friend (top), FotoRequest/Shutterstock (bottom)

Cerulean Warbler Joshua Galicki

From Wonder to Action

Birds fill us with wonder. They surprise us and delight us; they motivate us to learn, to explore, and to connect with others. By spending time noticing and appreciating the wonder of birds, we find hope.

And at American Bird Conservancy, that hope drives action — and yields results, including:

• Stable and even increasing populations in some parts of the breeding ranges of two of ABC’s highest-priority migratory birds, the Cerulean Warbler and Wood Thrush, thanks to collaboration through the ABCled Appalachian Mountains Joint Venture to implement conservation practices that improve the health and diversity of forests.

• The hatching of the first captive-bred Blue-eyed Ground Doves in Brazil, thanks to ABC partners Parque das Aves and SAVE Brasil with ABC support, leading the way for further recovery of this Critically Endangered species.

• Delivering big legislative wins for birds at the state level, including restrictions on harmful “neonic” pesticides in Vermont and Connecticut — protecting birds, waterways, and people alike.

• Data-driven science that tells us where to take action for birds most at risk, including our Gap Analysis, which reveals where gaps in habitat protection exist and must be closed to prevent bird extinctions in Central and South America, and the first-ever WatchList for bird habitats — pinpointing threatened habitat types most in need of conservation efforts in the United States and Canada.

As long as we have the capacity to wonder at and about birds, we have the ability to be inspired — and work together for positive change.

Thanks to a dedicated group of supporters, ABC has launched a special From Wonder to Action 1:1 Match Campaign, with a goal of raising $2 million for bird conservation by December 31. It's our most ambitious goal ever — one that equals our determination to act on behalf of birds.

Will you help us continue to build the bridge From Wonder to Action by making your most generous gift to ABC today?

Together, we'll turn inspiration into initiative, hope into habitat, and reverence into results for bird species across the Americas.

Give now by using the enclosed envelope, scanning the code, or visiting abcbirds.org/Wonder

Signal Boost

How the Motus Wildlife Tracking System is changing our understanding of the movements of birds, bats, and insects — and creating improved conservation outcomes

by Matt Mendenhall and Jen Newlin

William Blake, ABCʼs Pacific Northwest Motus Coordinator (red shirt), leads a team in installing a Motus station at Klamath Marsh National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon in 2024.

Jen Newlin

This past summer, a Wilson’s Phalarope nicknamed Mateo found social media acclaim after he traveled more than 8,000 miles from Utah’s Great Salt Lake to Argentina and back.

The discovery of the shorebird’s feat was possible thanks to the international Motus Wildlife Tracking System, a program of Birds Canada that has revolutionized scientific knowledge about animal migration since it debuted in 2014. Tracked birds, bats, and insects wear tiny tags that “ping” thousands of cell-towerlike Motus stations when they fly past, enabling tracking in near-real time.

Mateo is one of 28 Wilson’s Phalaropes tagged by Utah’s Tracy Aviary over the last two years as part of a study examining the movements of shorebirds at Great Salt Lake and beyond. Project leader Tully Frain and other conservation ecologists at the aviary knew that phalaropes flew long distances, but they didn’t know the route they took. They were astonished to learn that Mateo veered east and flew over the Gulf of Mexico from Texas, instead of heading south along the Pacific coast.

After being tagged in mid-June 2024 near Great Salt Lake, Mateo spent the next two months in Utah. On August 16, he was detected at Badger Island on the lake, took off toward the southeast, and nearly 33 hours later, he pinged a Motus station at Sargent, Texas, near the Gulf coast south of Houston. His trip covered more than 1,270 miles at an average speed of 39 miles per hour!

It’s unknown when he made it to Argentina, but in January and February 2025, he was near Mar Chiquita, a saline lake in the central part of the country. When the time came to migrate north, a Motus station in Guatemala picked up

his signal on May 4; two days later, he passed Roma, Texas, in the Lower Rio Grande Valley. Later that month, a station north of Denver, Colorado, detected him, and on May 22, he arrived near where he started, at the Great Salt Lake Shorelands Preserve.

The bird’s story is one of thousands that have been uncovered thanks to Motus. To put Motus into context, let’s consider humans’ long history of trying to understand birds’ seasonal movements. The recognition that birds migrate can be traced back at least 3,000 years, when Polynesians observed birds as they moved between islands in the vast Pacific. And for at least 275 years, western science has been working to understand the where, when, why, and how of avian migration.

We’ve learned a lot, of course, through banding birds and tracking them through radio and satellite telemetry, and by studying how various species use Earth’s magnetic field, the sun, the stars, and environmental cues to find their way. As bird populations have declined worldwide, migration studies have become more critical for conservationists as they work to preserve the places birds need during breeding, migration, and nonbreeding seasons.

Thanks to the advent of Motus, scientific knowledge about migration has increased in

A Wilsonʼs Phalarope nicknamed Mateo wearing a Motus tracking device rests in a trained banderʼs grip in Utah just before its release in June 2024. The bird was later tracked to Argentina and back to Utah. The ability to follow its remarkable journey occurred thanks to partners such as Tracy Aviary, Aves Argentina, Manomet Conservation Sciences, the Gulf Coast Bird Observatory, and other agencies and nonprofits.

Tracy Aviary

finer and finer details than was previously possible. In its first 11 years, Motus, which takes its name from the Latin word for movement, has revealed new information about dozens of bird species (as well as bats and insects).

“Motus is helping us close one of the biggest knowledge gaps in bird conservation — what happens to small migratory birds between breeding and nonbreeding parts of their life cycle,” said Adam Smith, the U.S. Motus Director and an ABC staffer. “For the first time, it has allowed us to track small species unable to carry larger tracking devices, such as satellite or GPS tags, and across entire continents — or even the hemisphere for some species.

“We know that many migratory birds are declining, but it has been incredibly challenging to figure out why for many of them, because we’ve been unable to follow them across their full annual cycle. That’s what Motus is changing. It’s not a silver bullet, but it's a powerful tool to see the otherwise invisible threads that connect a species' breeding, migratory stopover, and nonbreeding locations, and everything in between. Seeing those previously invisible connections helps us to identify risks,

understand population connectivity and trends, and make more informed decisions to manage and conserve species across their full life cycle.”

A Growing Network

Through September 2025, Motus users have tagged more than 60,000 animals of 472 species in 34 countries. More than 2,270 Motus stations are operating, collecting data for at least 1,000 scientific projects. Hundreds of collaborators (nonprofits, bird clubs, universities, government agencies, and others) participate in the program, and more than 2,000 landowners support Motus by allowing receiver stations to be placed on their property. And nearly 260 research papers have been published using Motus data, explaining new understandings of animal migrations.

ABC guides Motus efforts in the U.S., and since 2023, Smith and his team have installed or directly supported the installation of 122 Motus stations in 20 states or territories and three countries.

Smith leads three other ABC staff focused on Motus. As the U.S. Director, Smith works closely with the Motus leadership at Birds Canada to help grow a network of Motus partners and users in the Western Hemisphere. He supports partners in deploying Motus stations and looks for collaborative opportunities to leverage the technology to help fill critical information gaps for species of conservation concern. The goal is to make Motus a standard system for delivering real-world conservation outcomes, especially for vulnerable or imperiled species.

Todd Alleger serves as the Atlantic Flyway and Motus Technical Coordinator. He leads ABC’s Motus work along the Atlantic Flyway, especially from the mid-Atlantic northward and in the Caribbean (via strong partnership with Birds Caribbean). He helps ensure that Motus stations are built, installed, and maintained to the highest standards and supports and trains partners across the eastern U.S., Caribbean, and beyond to grow and sustain the network. He also

A Wood Thrush wears a Motus tracking tag just before being released.

Garrett Rhyne

This map shows the Motus stations (green dots) that detected a Wood Thrush’s tracking device during its fall and spring migrations, after it received the device in Long Point, Ontario. Like all Motus-tracked animals, its exact route isn’t known; the green and yellow lines connect the stations along its journey. The bird likely wintered in Honduras (where it was last detected in fall) or Nicaragua. Gray dots show other Motus tracking stations throughout North America.

works closely with Birds Canada and others to develop technical resources that benefit the entire Motus community.

Garrett Rhyne, the Motus Coordinator in the Southeast, works across the southern U.S. with state and federal wildlife agencies, universities, local bird groups, and others to expand and maintain a growing network of Motus stations across the region. He provides hands-on support for planning, installation, and maintenance, as well as tag deployment, and coordinates a large and active collaborative to ensure Motus continues to grow as a powerful tool for migratory bird conservation.

Similarly, William Blake helps build, install, maintain, and support Motus stations and tag deployment in six western states and sometimes Mexico as the Pacific Northwest Motus Coordinator.

Receiving Signals

Blake spends weeks on the road every year, logging thousands of miles. Before each trip, he packs a trailer, filling it with antennas, huge batteries, bolts, and cables; he plans his route through mountains, grasslands, and other remote areas; and he stocks food, including produce from his hobby farm, and lots of coffee.

Blake has been involved in about 80 installations since 2018. Last year, he and a few partners installed four new stations in a key migratory spot in Oregon that was considered a critical gap in the network, including one at the 40,000-acre Klamath Marsh National Wildlife Refuge in south-central Oregon. There Blake worked with Kaly Adkins, a regional wildlife biologist for the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW), Ken Popper, a local bird biologist, and the late Bob Sallinger, founder of Bird Conservation Oregon, spending two days installing the Motus station.

They hauled equipment from Blake’s trailer, using a red dirt road as a work station, and mounted solar panels and attached bulky antennas to an abandoned electrical pole. Cables connected it all to a computer. The crew then tested and tinkered and soon brought the station online.

For the Motus network to work, it needs station infrastructure and the wildlife tags themselves. Blake is part of both efforts. Trained and permitted researchers like him around the world tag individual birds, bats, and insects. While tags vary in size and type, they’re often tiny, solar-powered transmitters with an antenna, weighing less than 3-5 percent of the animal’s body weight. They can be attached like a little backpack. Tags send information when the individual flies close enough to a Motus station.

Motus tags enable researchers to study the animals’ movements without having to recapture them. Other tracking technology for small animals — GPS loggers and geolocators — store data, meaning an animal has to be caught again so its movement data can be downloaded. By contrast, Motus transmitters enable real-time tracking by wirelessly sending the data to any nearby Motus receivers. Depending on the transmitter and station configuration, most stations listen to a swath of sky about 18 miles wide.

Within days, the Klamath Marsh station picked up the signal of a passing Lewis’s Woodpecker. Excited texting followed. The tower’s first visitor happened to be a species Blake studied for his master’s thesis. “I’m always pretty relieved and excited to know a station is working,” Blake said. “It’s what I really like about my job — that I get to use hands-on technology to help people study and save bird species and habitats.”

Where Woodpeckers Go

As luck would have it, the woodpecker, Motus bird number 55979, was from a study biologist Kaly Adkins herself is leading for ODFW on Lewis’s Woodpecker migrations. Cameron Piper, a researcher from California, tagged the bird while working on the project for her master’s degree.

Piper and her all-women research team counted and monitored nests and tagged nine Lewis’s Woodpeckers in 2024 to better understand the home ranges and movement patterns of an Oregon population. Some birds are yearround residents. Others leave. But scientists didn’t yet know why that is, when the woodpeckers depart, or where some go in winter. Piper’s work, and Motus technology, helped provide new insight.

All nine of her tagged birds migrated, which surprised Piper. The bird that pinged the Klamath tower traveled from Piper’s study site in northern Oregon to areas north of Sacramento, California. Three others also flew to central California, four went to southwestern Oregon, and one evaded detection by Motus towers.

Now, researchers know more about Lewis’s Woodpecker migration timing and where at least some birds fly after the breeding season. Previously, they didn’t have data to verify that the birds traveled through the Klamath Basin wetlands. Now they do — a vital piece of information.

The Lewis’s Woodpecker is a federal Species of Concern, and scientists have many questions about where and when the birds are moving. Motus technology can help fill data gaps, Adkins said. Last year’s ODFW project team monitored 56 nests and hundreds of individual woodpeckers. “Motus helped us learn important information

A trained bird bander holds a Lewisʼs Woodpecker that was part of a Motus study in Oregon in 2024.

Stephanie Bartlett

Making Tracks

The 10 global bird species with the most individual Motus tags deployed (as of September 24, 2025).

Semipalmated

about a critical species,” Piper said, “and I hope we can use what we learned to inform studies on other Lewis’s populations.”

Knots Landing

One of the most-tagged species is the Red Knot, a once-abundant shorebird now

classified as Near Threatened, that has been a focus of conservation work (including at ABC) for decades. In the last few years, studies following Motus-tagged birds found that the shores of Delaware Bay — a famous stopover region for knots — were not the only major sites that the species relies on for refueling during spring migration. In fact, beaches in Florida and especially South Carolina also host great numbers of the birds when they’re heading north each year.

Motus detections recently confirmed that many Red Knots use the southeastern coast as a “launchpad” of sorts before their long flights north. They’ve been tracked through the eastern Great Lakes Basin or heading north along the Atlantic coast on their way toward James Bay, Hudson Bay, and their ultimate breeding sites in the boreal and arctic regions.

The discovery led to recent legal decisions in South Carolina that have curtailed the harvesting of horseshoe crabs — the birds’ primary food source — on key beaches from mid-March through May for the next five years. This significant win for bird conservation happened thanks to the Motus network.

Another species that stands to benefit from Motus-powered research is the Endangered Salt-

Sparrow. The orange-faced songbird is restricted to its namesake saltmarsh habitats from Maine to Florida. Earlier this year, Smith and several colleagues published new findings about the bird’s migration and stopover behaviors that can guide where and when to prioritize protection and restoration of coastal marsh complexes, among other conservation actions for the bird. They reported that the sparrows primarily move along the Atlantic coast, but some also appear to make inland and over-ocean migratory flights, particularly between southern New England and the mid-Atlantic. The team detected key stopover sites in coastal Connecticut, Rhode Island, New Jersey, and along

Joshua Galicki

marsh

Across the Plains

Similarly, in the central states and provinces, Motus is making a difference for grassland birds — the fastest declining group of landbirds in North America.

Kevin Ellison, ABC’s Program Manager for the Northern Great Plains, is a big fan of Motus technology. “Imagine how delightful it is to put a tag out there that could last five years and not have to recapture the bird to get any data back,” he said. “I’m enamored, having the ability to get information on species we haven’t been able to study like this before.”

Ellison and partners have been studying 10 different grassland species across four states, putting tags on 62 birds in the last two years. They’ve already recorded the first migrations of a Lark Bunting and a Horned Lark in the Great Plains. This fall, they’re tracking Bobolinks, Western Meadowlarks, and Brewer’s, Savannah, and Baird’s Sparrows, among others. Indeed, recent studies using Motus data have detected where and when Chestnutcollared and Thick-billed Longspurs, Sprague’s Pipits, and other grassland birds move

between breeding and nonbreeding areas. Birds from Canada and the northern U.S. have been tracked to sites in Mexico’s Chihuahuan Desert and farther south.

A single Chestnut-collared Longspur illustrates the value of tracking individuals. In June 2022, the Canadian Wildlife Service tagged the bird in southern Saskatchewan. About four months later, on October 19, at about 4:30 a.m., it flew past a Motus tower in southwestern Colorado — about 900 miles from where it started. At about 7 a.m. that same day, its signal was picked up at a Motus tower that had recently been installed at a national monument in northern New Mexico — 132 miles farther south, giving it an average speed of about 52 mph on that October morning.

A New Wrinkle

Recently in Costa Rica, a team of researchers turned to Motus to learn more about the Goldenwinged Warbler, a declining songbird with a flashy yellow head and a Zorro-like eye mask

ABCʼs William Blake works with biologists Ken Popper and Kaly Adkins after setting up a Motus tower.

that has been the focus of conservation efforts for many years.

Stu Mackenzie, Director of Strategic Assets for Birds Canada and the leader of Motus, joined biologists from SELVA, a Colombian nonprofit, ABC, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and others as they installed stations and tagged Golden-wings on their nonbreeding grounds. The team tagged 69 birds across habitats, from high-elevation forest to shadegrown coffee farms.

The researchers looked at whether the warbler’s winter habitat impacts migration timing. They expected that birds departing first in spring would subsequently arrive first on the breeding grounds. Instead, the Motus technology revealed that Golden-wings wintering in wetter and more forested areas would depart later in spring and would arrive around the same time or earlier than birds that left early. The findings show that Golden-wings have more than one strategy for migrating successfully, thanks in part to the habitat quality in their nonbreeding areas. The study adds an important new piece of information to our knowledge of this well-studied yet threatened songbird.

Why Motus Matters

In the decade-plus since Motus launched, its value for scientific study and conservation planning has continued to grow year after year. In addition to teaching researchers how animals navigate landscapes and barriers, it also informs them how to protect species in decline, like safeguarding the precise habitats they use.

“One of the most groundbreaking things about Motus is that it provides us with the ability to monitor from local to regional and even continental movements, and find miraculous insights in between,” Mackenzie said.

In many ways, Motus is perfect for studying wildlife wallflowers: the small species. The weird ones. The shy ones. The ones, frankly, we know the least about. The ones that don’t

fit, literally, into historical movement research methodology. Sure, challenges pop up: keeping stations online in winter, false detections, technological glitches, slow website load times. But progress is happening, one tag and tower at a time.

Thanks to the vast Motus network of researchers, installers, funders, and others, it’s clear that this revolution in migration studies will continue. Smith and his crew, for example, expect to help install more than 30 new stations in the U.S., Mexico, and the Caribbean in 2026. Adkins is diving into a Northwest-wide project to tag and study migratory patterns of hoary and silver-haired bats. And Piper has put another nine tags on Lewis’s Woodpeckers this year and is waiting to see what happens.

Mackenzie said it best: “The most powerful thing is the true collaborative nature of this work and seeing how the conservation community can rally behind an idea.”

Matt Mendenhall is ABC’s Managing Editor. Jen Newlin is a freelance writer, illustrator, and strategist focused on conservation and wildlife. Learn more at jennewlin.com.

Acknowledgments

ABC thanks the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Tareen-Filgas Foundation, Birds Canada, U.S. Forest Service, USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, Sam Shine Foundation, National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, Robert Hemphill and Leah Bissonette, and the state wildlife agencies of Alabama, Florida, New Jersey, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Texas for supporting our Motus projects.

Enjoy a video about a Virginia Motus station that is part of an effort to track Rusty Blackbirds and other species. abcbirds.org/WatchMotus.

At motus.org, you can explore tracks of individual animals, zoom in on Motus stations, find research papers, and more.

Motus tracked a Chestnut-collared Longspur from Saskatchewan to New Mexico in 2022.

The Flute

Old bones from coastal Maine reveal ancient secrets of kinship between people and birds

by Alice Hotopp

Archeological texts often list “perforated bone tubes” among artifacts unearthed from early humans’ caves and burial sites. “Perforated bone tubes,” in its clinical language, is a name that aims to describe the artifacts without assigning function. Archeologists theorize that these bones may have been brought to one’s lips and used as whistles or bird calls. Objects made for utility, for drawing birds from the air during a hunt. Maybe this is so. Yet, they could also be interpreted as flutes — things made to please the soul.

Such artifacts may hold evidence of human minds awakening to music — signs of our ancestors turning bone and air into song and of an ancient ability to feel beauty piercing our chests. An innate yearning to be beauty’s mimic.

One late January day, I visited a grassy point overlooking the bay on the west side of Maine’s Schoodic Peninsula. The Point, within Acadia National Park boundaries, has picnic tables, fire rings, and a pier jutting out into the water. The wind had swept a recent snowfall into drifts along the field. A few Buffleheads bobbed in the turning tide’s cobalt waves. I walked along the cobble shore, studying the edges of the field that are crumbling into the water.

Archeologists found a perforated bone tube at this place in 1978. They excavated it along with tools, bits of pottery, mammal and bird bones, and soft clam shells — traces left by the ancestors of the Wabanaki. Meaning “People of the Dawnland,” Wabanaki is the collective name for

The Schoodic Peninsula in Maineʼs Acadia National Park has yielded many Indigenous artifacts.

the tribes — the Maliseet, Mi’kmaq, Passamaquoddy, and Penobscot — who live in what is now Maine and the Canadian Maritime provinces, their indigenous homeland.

Wabanaki ancestors lived on Schoodic Peninsula, hunting and gathering food at the Point long before it became a place where tourists like me eat their turkey sandwiches and potato chips.

Connections Run Deep

Following the lead of Wabanaki community members, Olivia Olson, who recently earned a master’s from the University of Maine, calls this bone a flute. She studied the artifact and other animal bones from the Point, which is one of an estimated 2,000 “shell-bearing sites” found along the coast and islands of present-day Maine. These sites, which range in age from 2,000 to 5,000 years old, are composed of the shells of oysters, mussels, and clams and the bones and teeth of vertebrate animals — items deposited by Wabanaki ancestors.

These piles of calcium carbonate and collagen, through which blood once pulsed, are a throughline of deep Wabanaki relation with the region’s coastline and islands. Bonnie Newsom, Associate Professor of Anthropology at the University of Maine and a Penobscot Nation citizen, and her coauthors of a 2023 paper describe the significance of these sites: “For the Passamaquoddy and other Indigenous communities living in these regions, coastal shell-bearing sites are remnants of a built heritage that evoke cultural connections to place.”

Sadly, many of the sites, which may have been used until European settlers displaced Wabanaki communities, are eroding into the sea. Intensifying coastal storms and rising sea levels that wash away shell sites are yet more forces displacing the Wabanaki from their cultural heritage.

Below Buffleheads fly above the water, just as they have for thousands of years.

Right An artistʼs depiction of a flute that was carved from a bird bone.

Don Laidlaw/Shutterstock (left), Coco Faber (right)

The objective of Olson’s research was to reconstruct the past avian assemblage of the Point — in other words, to identify the living, breathing birds to which the bones in the shell heap once belonged, to learn how these animals might have interacted with each other and with Wabanaki ancestors.

“You can learn so much from studying the birds: what season people were harvesting in, what the environment was like, what sort of habitat and fragmentation was present at the site, if there was a breeding colony nearby,” she told me. “The big question of my thesis was, how were humans and birds interacting, not just in a food way or subsistence way, because that has been done before. But because of the flute, and because of the cultural significance of birds today, I’m asking what else could the birds have been, what other roles could they have played in people’s lives in the past?”

The flute, she explains, captured the awe of attendees of a 2022 event that brought together Wabanaki representatives, archeologists, Indigenous language speakers, cultural resource managers, and Acadia park staff. When artifacts from the Point, including the flute, were shared with attendees, Wabanaki citizens had questions: Why hadn’t they seen the flute before? What was it made of? How old was it? What was its past significance? What does it mean for contemporary and future relations with birds and the land? So, under

Newsom’s mentorship, Olson has been piecing together the story of the flute, tracing the threads of kinship between people and winged creatures of the Point, both past and present.

Decoding Bird Bones

To do her research, Olson sifted through boxes of bones collected from the site, asking which species each belonged to, what each shard of bone may represent — an instrument, a fishhook, dinner. These objects, including the flute, had been housed with the National Park Service for decades and went unshared with Wabanaki communities. Reports from excavations were written dryly, with the language, emotion,

For her master’s work, Olson dug into reanalyzing the once-obscured bones and into reconstructing the Point’s ecology, and she did so with Wabanaki communities at the heart of the story — sharing findings and interpretations, connecting past and present cultural practices, incorporating Indigenous language for objects and animals.

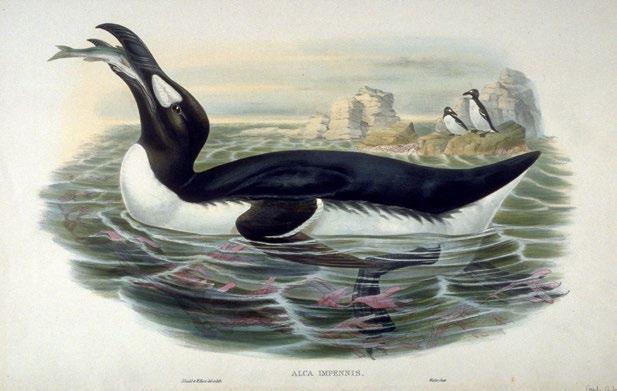

From the archive of 829 bird bones, she identified geese, cormorants, gulls, ducks, extinct Great Auks, loons, and an eagle. In her thesis, Olson traces how each of the birds was sustenance for body and spirit. From their patterns of occurrence, she suspects that Wabanaki people harvested birds on the Schoodic Peninsula predominantly during spring

Olson sifted through boxes of bones, asking which species each belonged to, what each shard of bone may represent.

and relations of the people who had been home at this place largely removed from the narrative.

and fall migration. Their meat and eggs were eaten, their fat rendered into oil, their feathers woven into

Edward Lear/The Birds of Europe by John Gould (Wikimedia Commons)

The Great Auk, which went extinct in 1844, was among the species the Wabanaki people relied upon.

hats. Birds fly through Wabanaki legends: Eagles appear as fearsome leaders, loons as harbingers of good weather, and the sight of swans at dawn signifies the Great Spirit.

Places throughout the region bear their names. The town of Casco, for example, has as its root the Penobscot word kasqu, which means “heron.” Frankfort was once called “black duck stream” (kʷikʷimə ssəwihtəkʷ in Penobscot); the Penobscot name for the Sheepscot River (Sipsaconta) meant “little birds flock or rush.”

Depictions of birds also appear in both ancient and contemporary Wabanaki art — petroglyphs, baskets, beadwork, and masks.

In her thesis, Olson summarizes, “[Birds] were not only food items, but also teachers, bone providers, messengers, weather forecasters, feather repositories, guides, and musical inspiration… The multiplicity of uses points to the commonly held Indigenous philosophy of using the whole animal once harvested. The whole animal, in this case, means its meat, eggs, feathers, bones, and spirit.”

I picture the long-hidden bones she analyzed for her research. I see them lifting from their storage boxes into the sky — the lives and deaths of these winged beings finding their place in the ongoing story of Wabanaki connection to Schoodic Peninsula.

When I ask what the flute looks like, Olson pulls up images on her computer screen of the sandstonecolored bone against a black back-

ground. Roughly 5.1 inches (13 cm) in length, the flute has a larger hole on one side for the mouthpiece and three smaller holes along its length. Its edges are jagged, having splintered over the years. The flute, she has hypothesized, is made from the ulna (a wingbone) of a swan or a goose. It may be 2,000–3,000 years old.

Swans are an atypical sight in Maine today. Tundra Swans occa-

Birds whose bones were used by Wabanaki people include Bald Eagle, Great Cormorant, Green-winged Teal, and Common Loon.

sionally winter in the region, and Trumpeter Swans have been sighted in southern Maine in recent years. Tundra Swan bones have been identified from another Wabanaki shell heap on the island of North Haven, off the state’s central coast.

The specific bone that became this particular flute may have ended up on the Schoodic Peninsula through trade with people from another region. Or, the flute may have been an heirloom, passed down from a generation that had migrated from elsewhere. Olson said it is still unknown if people used the hollowed bone in ceremony, casual music-making, or attracting birds during a hunt. She notes that it’s possible that the flute

had many uses, as these instruments appear as both pragmatic tools and magical objects in Wabanaki lore. (In Wabanaki languages, there is no known distinction between a “flute” played for music and a “whistle” played for utility.)

Flutes of Long Ago

Flute playing may have accompanied spoken poetry and dancing; it’s thought that songs played on flutes elicited feelings such as sweet love and deep loneliness. Wabanaki legends tell of Megtimoowesoo, a fairy-like creature who played the flute, and of flutes charming people into dance. Notes drifting from a

flute were said to draw lovers, game animals, and whales to the player. Regardless of the Schoodic flute’s purpose, Olson said the artifact underscores deep spiritual connections between people and birds. These bonds are seen across cultures. Flutes made of the wing bones of vultures, swans, cranes, condors, and turkeys have been uncovered from around the world, at archeological sites in Germany (30,000–40,000 years old), France (28,000–32,000 years old), China (7,400–8,300 years old), and Peru (about 4,450 years old). Sites across present-day Maine and the Canadian Maritimes have produced more than 30 bird bone flutes. In Port au Choix, Newfound-

The flute that is the focus of this story may have been carved from a wing bone of a Tundra Swan.

land, researchers uncovered 15 flutes made from the ulnae of swans, geese, and eagles at the burial site of 117 people. At the site, which appears to have been active from 3,450–4,870 years ago, caribou antlers carved into bird effigies were also found with the dead. The oldest of the flutes from the Northeastern coast of North America, from 8,000 years ago, was found in Labrador buried with a child, only 11–13 years old. Was this flute placed tenderly with the body of the child to bring them joyful music in the afterlife? To accompany their soul in its flight from the Earth?

When I read about these flutes carved from avian bones — found across cultures and ages of human existence — I wonder about the convergence of wonder. About the origins of music. About humans across space and time looking to the sky, marveling at the long-winged beings passing overhead. Mimicking the beauty of flight with notes resonating from the bones of wings.

At the Point on Schoodic Peninsula, my mind reels back 2,000 years. The picnic tables, fire rings, pier, vacation homes across the bay, and my body all melt away. Someone stands at the edge of the water. They gaze at Buffleheads bobbing on cobalt waves. Their belly is full of the meat of an eider. Later, they will sharpen the eider’s bones into fishhooks, linking life and death between land, water, and sky. They press their lips to the bone of a swan. The bone that once supported lean muscle and white feathers. The bone that once soared through the sky. The bone

About This Story

This essay and the accompanying artwork are published with the permission of Olivia Olson, Emily Blackwood, Bonnie Newsom, and Rebecca Coe-Will, who each conduct research on Schoodic Peninsula’s shell heap sites in collaboration with Wabanaki communities. The author, Alice Hotopp, and artist, Coco Faber, are European descendents and not members of the Wabanaki community. Alice and Coco are both trained bird biologists. We have worked to present this story with scientific integrity and deep respect for Wabanaki histories, knowledge, and sovereignty.

The National Park Service stewards thousands of archeological sites as cultural resources. Archeological sites within Acadia National Park are now co-stewarded with the Wabanaki Community. As such, NPS preserves and protects them under federal laws, including the Archeological Resources Protection Act that regulates the excavation and removal of archeological resources and can impose penalties for unauthorized activities.

Olivia Olson’s 157-page master’s thesis about human-bird relationships in the Wabanaki homeland in Maine at digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/4201

that still connects the Wabanaki to the music of this coast — salt and wind, waves and forest, wings and scales and shells and hands drilling holes into bone.

Alice Hotopp (alicehotopp.com) is a Maine-based ecologist and writer. She holds a PhD in ecology and environmental sciences from the University of Maine. She also serves as a Together for Birds Storyteller, working with Veronica Padula (ABCʼs 2024 Seabirds and Stories of Multi-Species Kinship Fellow) and Sea McKeon (ABC’s Marine Program Director),

with support from Naamal De Silva (ABC’s Vice President of Together for Birds). In this role, Hotopp is collaborating with artist Coco Faber to create Atlas of Kinship, a book of short essays and paintings that reimagine traditional scientific atlases.

Watch an ABC webinar featuring Alice Hotopp and others from our Marine and Fellows Programs about stories of kinship with seabirds. abcbirds.org/SeabirdKinship

Olivia Olson

Northern Pintail

Keeping Watch

Introducing the first-ever ranking of U.S. and Canadian bird habitats by threat, spotlighting those most in need of conservation action by

Molly Toth

The Florida Scrub-Jay is a species so inextricably bound to its habitat that it’s right there in the name. The intelligent and inquisitive corvid is highly social, and extended family groups act as the connective tissue that ensures the future of the species: Young from breeding seasons past stay local to help their parents raise the next brood.

When younger scrub-jays disperse and claim their own breeding territories, they don’t travel far from where they hatched, and

they seem to have an aversion to crossing any areas that aren’t the scrub oak habitat for which they are named. Increased development has created disconnected patches of scrub oak, meaning these socially connected jays, already given to remaining close to home, are adrift on ever-shrinking islands and at serious risk of extinction.

As goes the Florida Scrub, so goes the Florida Scrub-Jay.

Left A Florida Scrub-Jay perches in its scrub habitat in central Florida, one of the most threatened on the Habitats WatchList.

Right The Habitats WatchList map at abcbirds.org displays a range of colors for the 100-plus habitats it identifies.

A Watch List for ‘Where’

The Florida Scrub-Jay is classified as a Red Watch List species by Partners in Flight in its ranking of species of conservation concern. It is extremely vulnerable because of its small population and range, the high degree of threats it faces, and declines across its range. Partners in Flight’s Watch List system uses a suite of vulnerability factors to score species and proactively put those facing the toughest challenges at the top of the list for conservation prioritization: the Red Watch List.

No analogous list ranking habitat vulnerability existed, but ABC President Michael J. Parr and Senior Conservation Scientist David Wiedenfeld had long discussed the need for such a tool, one that is informed by — and, in turn, can inform — bird conservation. What was missing, they thought, was a watch list for where a bird lives that would present a species in the broader context of its habitat and ecosystem.

“Habitat is the foundation of bird conservation — no bird can survive without the right amount of the right kind of habitat, and habitat degradation is a leading driver of the massive species declines we have seen in recent de-

cades,” said Parr. “We saw a need for a system that could tell us which habitats the most endangered birds are using and understand what threats those places and birds are up against.”

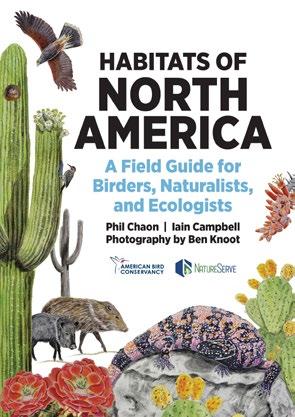

In a moment of serendipity, Parr and Wiedenfeld realized that their model for thinking about habitats through the lens of birds, in addition to commonly considered factors like vegetation, was also taking form elsewhere. Ecologist and nature guide Iain Campbell was at work on a book, Habitats of North America: A Field Guide for Birders, Naturalists and Ecologists, that did just that. This guide was designed to make habitats very understandable for the general public, with evocative descriptions, numerous illustrations, silhouettes, and photos of the wildlife that live there. The habitat classifications Campbell and coauthor Philip Chaon identified evolved parallel to and eventually harmonized with Parr and Wiedenfeld’s efforts to evaluate and rank habitats by the threats they face and their importance for birds.

Their work culminated in the release of the Habitats WatchList (officially the WatchList of Terrestrial and Freshwater Bird Habitats of the U.S. and Canada) that launched on ABC’s website,

abcbirds.org. The WatchList and an accompanying map tool empower users — from biologists to backyard birders — to learn about the habitats around them and the threats they face.

“In order to identify which habitats are most threatened, we needed to identify the main drivers of habitat loss, and a way to show which habitats were being impacted most by those drivers,” said Wiedenfeld. “We’ve developed a scoring system designed to capture that information.”

Assessing Vulnerabilities

“Birds relate to habitats, and habitats relate to birds,” explained Wiedenfeld. “Birds are very visible and easy to identify, more so than plants, insects, or mammals. They can be a useful mechanism to get people to understand what habitat they’re looking at.”

For the new Habitats WatchList, Campbell, Chaon, Parr, Wiedenfeld, and ABC partner NatureServe used vegetation and assemblages of bird communities to help identify discrete differences between habitat types, with NatureServe providing vegetation classification expertise and mapping. While some habitats are easily distinguished from others — Florida Scrub and Jack Pine Forests, for example — others are more difficult to define. Bird communities can be the factors that create the boundaries.

Early Successional Temperate Forest and Nearctic Temperate Deciduous Forest may even have many of the same plants, but they don’t share the same feathered friends.

Birds are both a defining characteristic of habitats in this model and a metric to be measured. The presence, number, and conservation status of Indicator Species in a given habitat are key factors. The higher the number of Indicator Species (specialist bird species found only in one or very few similar habitats), the greater the conservation risk to that bird habitat.