Śrī Vilāpa kusumāñjali

of Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī

Volume One

Commentary by Śivarāma Swami

Commentary by Śivarāma Swami

Commentary by Śivarāma Swami

The “Kṛṣṇa in Vṛndāvana” series:

Śuddha-bhakti-cintāmaṇi

Veṇu-gītā

Na Pāraye ’Ham

Kṛṣṇa-saṅgati

Śrī Dāmodara-jananī

Saṅkalpa-kaumudī – A Moonbeam on Determination

Other Books by Śivarāma Swami:

The Bhaktivedanta Purports

The Śikṣā-guru – Implementing Tradition Within iskcon

Śikṣā Outside iskcon

Nava-vraja-mahimā, Volumes 1-9

Sādhavo Hṛdayaṁ Mahyam – Saints Are My Heart

My Daily Prayers

The Awakening of Spontaneous Devotional Service

Varṇāśrama Compendium Volume 1. The Varṇas.

Gauḍīya-stotra-ratna - The Gemlike Prayers of Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇavas

Śrī Vilāpa-kusumāñjali – A Rendering

Chant

Chant More

Based on the writings of A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupāda and the previous ācāryas

Commentary by Śivarāma Swami

Kṛṣṇa in Vṛndāvana Volume Six

Śrī Vilāpa-kusumāñjali of Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī Volume One

© 2022 Śivarāma Swami © 2022 Lāl Publishing, Hungary

Managing Director: Manorāma Dāsa

Editrix: Braja Sevakī Devī Dāsī

Assistant Editor: Ānanda Caitanya Dāsa

Copy Editor: Mahābhāva Dāsa

Sanskrit Editor: Gabhīra Dāsa

Mañjarī Devī Dāsī

Art Director: Akṛṣṇa Dāsa

Artists: Gāndharvikā Devī Dāsī

Taralākṣī Devī Dāsī

Smṛti-pālikā Devī Dāsī

Layout & Design: Sundara-rūpa Dāsa

Indexing:

Revatī Devī Dāsī

Respects and thanks to those who also contributed to this book: Kamalanātha, Śeṣa, Senāpati, Kṛṣṇa-Caitanya, and Śyāma Vṛkṣa.

Special thanks and much gratitude to Vidyāgati Devī Dāsī for making the printing of this book possible.

Quotes from the books, lectures, letters, and conversations by His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupāda © The Bhaktivedanta Book Trust International 1966-1977. Used with permission.

ISBN 978-615-5253-21-8 Printed in Hungary

Readers interested in the subject matter of this book are invited to visit the following website: www.sivaramaswami.media

This book is dedicated to Śrīla Prabhupāda, who taught that chanting Hare Kṛṣṇa means to request Śrīmatī Rādhārāṇī to accept us as her maidservants and thus engage us in her service.

In the beginning of the Hare K ṛṣṇ a mah ā -mantra we first address the internal energy of Kṛṣṇa, Hare. Thus we say, “O Rādhārāṇī! O Hare! O energy of the Lord!” When we address someone in this way, they usually say, “Yes, what do you want?” The answer is, “Please engage me in your service.” This should be our prayer.

–– His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupāda, Teachings of Lord Kapila 32, Purport.

I o er my respectful obeisances to the lotus feet of my spiritual master, who has o ered me safe passage along the path leading from the fiery maze of material enjoyment to the secure refuge of Vraja’s divine couple. Through his books, spoken words, and inner guidance, Ś r ī la Prabhup ā da taught me the process of pure devotional service. As a result of his teachings, an aspiration has awakened in me to serve Kṛṣṇa in the way of the Vraja-vāsīs, specifically in the way that Rati-mañjarī serves Śrīmatī Rādhārāṇī.

May His Divine Grace continue to guide me along the journey of sādhana-bhakti enriched with spontaneous attachment, a journey that leads to the destination of ecstatic devotion and realisation of my spiritual form.

All glories to Śrī Rūpa Gosvāmī, who, through his teachings, has revealed Caitanya Mahāprabhu’s divine mission to the world, and who has inspired my gurudeva and his loyal followers to spread those teachings to every town and village.

May Śrī Caitanya Mahāprabhu confer his blessings upon all sincere devotees who dedicate themselves to knowing and serving his mission, devotees who show by example what it means to go back home, back to Godhead.

I bow before the lotus feet of my worshipable deities, R ā dh āŚyāmasundara. May they fulfil the humble entreaty of an old man

who has dedicated his life to their service and who harbours the long-standing hope of securing their mercy.

With a clump of straw between my teeth, I bow before Śrī Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī, ever grateful that my guardians and well-wishers have shown me the path to his lotus feet. May he take the hand of this follower and introduce him to the service of Śrīmatī Rādhārāṇī.

śrī-rādhikā-prasādārthaṁ vilāpa-kusumāṇjaliḥ nirmito yena tasmai śrīdāsa-gosvāmine namaḥ

I o er my respectful obeisances unto the lotus feet of Ś r ī Raghun ā tha D ā sa Gosv ā m ī , who, in his unwavering desire to please Ś r ī mat ī R ā dh ā r āṇī , disclosed the contents of his heart by composing this plaintive flower-o ering of prayers, Śrī Vilāpa-kusumāñjali.

All glories to the glistening touchstone seated in the crown of the personified Vedas, Śrī Vilāpa-kusumāñjali, the devotional radiance of which pierces the heart’s deepest recesses and awakens a desire to become the object of a gopī ’s mercy.

I o er my respectful obeisances to those Vaiṣṇavas in pursuit of pure devotion, and to the great sādhus who have been instrumental in guiding me to my current aspiration. By comparison to my predecessors, I am insignificant, yet I dare to embark on this work of composing commentary on Vil ā pa-kusum ā ñjali. O merciful Vaiṣṇavas! I fall at your feet and pray,

“Bless me that I may do justice to this great work, its original author, and the confidential service of Śrī Rādhā.”

Śivarāma Swami

Nityānanda-trayodaśī

Śrī-dhāma Māyāpur, 2022

Sometime approaching my twentieth year in Kṛṣṇa consciousness, I became increasingly aware that to go back to Godhead I needed to be clearer about the process taking me there. If I was not, would I get there? My analytical engineer’s mind said “No!”

By then Ś r ī la Prabhup ā da had left our vision, but his books remained. Thus I began to study in a more purposeful way than ever before.

The goal was clear: we wanted to go to Goloka Vṛ nd ā vana and play with K ṛṣṇ a either as gopas or gop ī s. But what was the means by which we reached there? What did it mean “to play with Kṛṣṇa?” In time I understood that there had to be a correspondence between the goal and the means, and since the goal was spontaneous loving service, the means to attain that was spontaneous practice, rāgānuga-bhakti.

I must admit that it took a while to assuage the fear that I was headed down the path of deviants. However, continued study and, even more importantly, association with senior Vai ṣṇ avas,

reassured me that spontaneous devotional service was what Kṛṣṇa consciousness was ultimately about. Rather than deviating, I was reaping the benefits of two decades of service, and receiving Śrīla Prabhupāda’s guidance. I surrendered.

Removing these psychological blocks allowed me to read Śrīla Prabhupāda’s books with new eyes, and to take the courage to read other books as well. I, along with everyone else of our devotee generation, had been taught that aside from His Divine Grace’s books, everything else was either bogus or o limits. But Śrīla Prabhupāda countered that misunderstanding, and about the previous ācāryas’ works he said,

Devotee 1: Śrīla Prabhupāda, I remember once I heard a tape where you told us that we should not try to read the books of previous ācāryas.

Prabhupāda: Hmm?

Devotee 2: That we should not try to read Bhaktivinoda’s books or earlier books of other ā c ā ryas . So I was just wondering...

Prabhupāda: I never said that!

Devotee 2: You didn’t say that? Oh.

Prabhupāda: How is that?

Devotee 2: I thought you said that we should not read the previous ācāryas’ books.

Prabhupāda: No, you should read.

Devotee 2: We should?

Prabhupāda: It is misunderstanding.1

So about books other than his own Śrīla Prabhupāda said, “No! You should read.”

And I did!

At that time, my godbrother Ku ś akratha D ā sa was translating Gau ḍī ya literature. I acquired his entire collection and read everything, some repeatedly, especially relishing the works of Raghun ā tha D ā sa Gosv ā m ī , R ū pa Gosv ā m ī , Vi ś van ā tha Cakravart ī , and Prabodh ā nanda Sarasvat ī . But there was a lot of content, and understanding the truths and sādhana of rāgānuga-bhakti was not happening overnight. While śāstra remained the basis, it

was not until I had the guidance of advanced Vaiṣṇavas, like Gour Govinda Swami, that the pieces of spontaneous devotion began to fall into place.

But did I have the qualification?

I was certainly a steady s ā dhaka. I never missed the morning program, I worshipped my deities, never broke the regulative principles, never neglected my rounds. And, in Śrīla Prabhupāda’s words in the verse below, I started o with an “inclination to spontaneous loving service,” which, through reading and association, grew into an eagerness to follow Vraja-vāsīs.

If I had qualification it was based on my good past-practices and my interest in following the Vraja-vāsīs. Then I read what Caitanya Mahāprabhu and Rūpa Gosvāmī said about the eligibility to step into the realm of natural devotion:

sevā sādhaka-rūpeṇa siddha-rūpeṇa cātra hi tad-bhāva-lipsunā kāryā vraja-lokānusārataḥ

The advanced devotee who is inclined to spontaneous loving service should follow the activities of a particular associate of Kṛṣṇa’s in Vṛndāvana. He should execute service externally as a regulative devotee as well as internally from his self-realised position. Thus he should perform devotional service both externally and internally.2

It was clear from this verse that if I was serious about exploring this new facet of bhakti-yoga, I could, and should, move forward. In my mind there was never any question of which Vraja-vāsīs I wanted to follow. It was the gopīs.

I first heard a Kṛṣṇa-Radio rendition of The Song of the Flute in 1971, and since that time I had a natural attraction to the atmosphere and devotion generated by the gop īs’ talks. My attraction was just a seed, but still it was a seed. Much later, in discussions with my friend Tam ā l Krishna Goswami, we concluded that the gopīs we sādhakas should follow were the mañjarīs.

In this way the direction of my devotions was becoming clearer. Then along came R ā ga-vartma-candrik ā ; the trilogy, Bindu, Kiraṇa, and Kaṇā3; and Vilāpa-kusumāñjali. Added to that, Kṛṣṇa arranged that I meet a senior Gau ḍī ya Vai ṣṇ ava who was both kind enough and learned enough to expand upon the foundations of spontaneous devotion and its full manifestation in Vilāpakusumāñjali.

From that point on, topics of Kṛṣṇa in Vṛndāvana became my life. However, I observed that in iskcon , even senior devotees shared an aversion to the topic of spontaneous devotion. On the other hand, many immature devotees were leaving Śrīla Prabhupāda’s movement for gurus claiming to dispense rāgānugā.

Somehow I felt a calling to address this situation and to write about the science of spontaneous devotion in a way that Ś r ī la Prabhup ā da would approve. I was convinced that Ś r ī la Prabhupāda’s line should present the truths of its perfection, that it should inspire old devotees to brave forward, and that it should stop new devotees from searching after elusive greener pastures. Śrīla Prabhupāda’s pasture was the greenest!

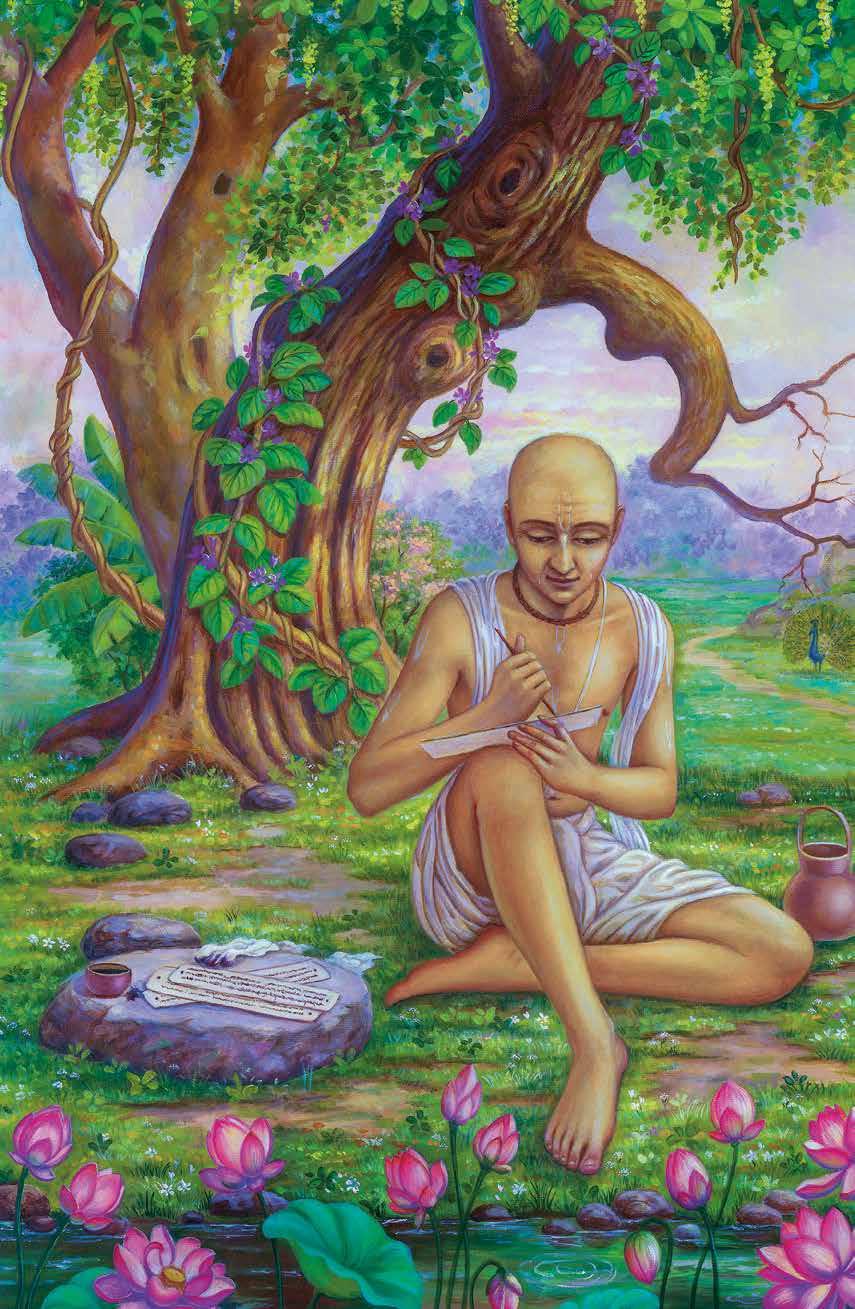

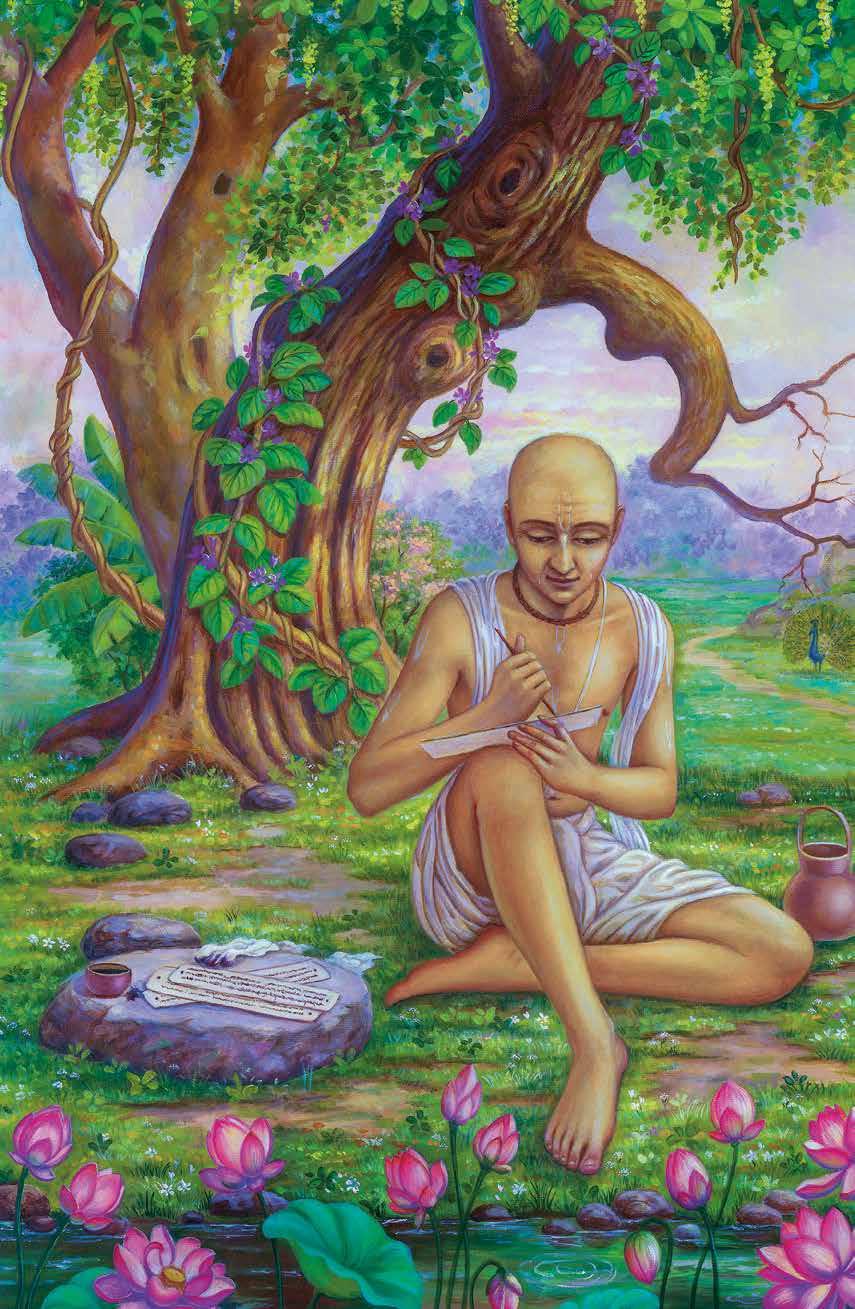

Gradually I began to share my realisations through books, beginning with the “Kṛṣṇa in Vṛndāvana” series, and thereafter with other publications like Nava-vraja-mahimā. While writing in the latter about Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī, I thought of composing Vilāpakusumāñjali along with a brief commentary, and somehow including it in the text. But where? Since such a work would be too long for the main narrative of short pastimes, I decided to place it into the Appendix. So Volume Four of Nava-vraja-mahim ā gained a 300-page Appendix. It was almost half the book.

But I was not satisfied.

It was short, and I still had so much more to say. But I had to move on and complete Nava-vraja-mahimā, and then other books. And even as I did, it would be a rare day that I did not meditate on a verse of Vilāpa-kusumāñjali, or perhaps some kindred book like Viśākhānandābhidha-stotra.

Another ten years went by.

After further personal development, I made up my mind to write a more comprehensive commentary. Was I qualified?

I had been through that question-answer dynamic too many times with other, admittedly less rasika books. Both the internal and external confirmations were too compelling, and so I began the planning process.

About the internal confirmations I shall not, should not, speak. The Lord has instructed us not to: sarvaṁ sampadyate devi deva-guhyaṁ susaṁvṛtam

That which is very confidential is successful if kept secret. Even if someone enquires, it should not be disclosed.4

The external confirmations were many. In discussing the project with respected godbrothers, I met with overwhelming support. Colleagues who shared a similar interest in rāgānuga-bhakti constantly encouraged me to begin. From unsolicited sources worldwide, from devotees who knew nothing of my intent, I received letter after letter saying that the Appendix-Vilāpa-kusumāñjali was what they had always been looking for in spiritual life. And one evening in Vṛndāvana, a talented artist, Gāndharvikā Devī Dāsī, approached me and asked if she could paint for my books. She, too, shared a passion for Dāsa Gosvāmī ’s work, and her art graces the pages of this book.

And so here I sit in M ā y ā pur, just after Gaura-p ū r ṇ im ā , and eighteen months into Vilāpa-kusumāñjali. Volume One comprises the first seventeen verses, and will go to print in a few months, followed by another four volumes over an anticipated three years. The entire five-volume set will be completed sometime around 2025, or soon thereafter. I have, as of this day, written up to Verse Thirty-four, which amounts to one-third of the book.

Yes, it is a long work. The commentaries average thirty to forty pages per verse, and there are one hundred and four verses. However, I have accepted that the elaborate exposition of mellows, truths, and pastimes is the way Kṛṣṇa moves my pen. Moreover, in-depth presentations attract devotees more than condensed ones. They allow readers to carefully explore the relevance of D ā sa Gosvāmī ’s book to their own spiritual lives.

Even before I started, I knew that writing this book would signal a milestone in my spiritual life. It would be my bhajana, my means of purification, in the way that Kavirāja Gosvāmī expresses in his magnum opus: jāni vā nā jāni, kari āpana-śodhana

Whether I know it or know not, it is for self-purification that I write this book.5

As I write, I learn and progress. Scouring Śrīla Prabhupāda’s books, as well as the works of ācāryas such as Jīva Gosvāmī, I associate with these great souls, with their teachings, with the Vraja-v ā s ī s they praise. In this way my personal eagerness for vraja-bhakti, and for a place among Śrīmatī Rādhārāṇī ’s attendants, increases day by day, verse by verse.

My conviction is that if I follow the lead of D ā sa Gosv ā m ī ’s verses with a sincere e ort to praise Rādhā-Kṛṣṇa and their entourage, my commentaries will be of service to sādhakas and siddhas in furthering their own relationship with the divine couple.

Someone may challenge how a practising devotee like myself can dare to comment on Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī ’s masterpiece, and how I can be so presumptuous as to think that my words will benefit even advanced Vaiṣṇavas.

My answer is that I have repeated in my own words what I have heard from great authorities. Whatever my methodology, still the truths, pastimes, and mellows described in this book are authentic. Expressing the subject matter of the verses by means of conversation between the book’s characters is an application of the literary principle called p āṅ ji- ṭī k ā , or further explanations of a subject. 6 The author of Caitanya-caritāmṛta describes his own narration of Caitanya Mahāprabhu’s pastimes as an elaboration on the notes kept by Svarūpa Dāmodara and Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī. He posits that such literary composition is akin to flu ng out compressed cotton.

R ū pa Gosv ā m ī also presents a similarly beautiful answer to those critics who may still hold an objection to my commentary on Vilāpa-kusumāñjali:

abhivyaktā mattaḥ prakṛti-laghu-rūpād api budhā

vidhātrī siddhārthān hari-guṇa-mayī vaḥ kṛtir iyam pulindenāpy agniḥ kim u samidham unmathya janito hiraṇya-śreṇīnām apaharati nāntaḥ-kaluṣatām

O learned devotees! I am by nature ignorant and low, yet even though it is from me that the Vidagdhamādhava has come, it is filled with descriptions of the transcendental attributes of the Supreme Personality of Godhead. Therefore, will not such a literature bring about the attainment of the highest goal of life? Although wood may be ignited by a low-class man, its fire can nevertheless purify gold. Similarly, although I am very low by nature, this book may help cleanse the dirt from within the hearts of the golden devotees.7

I am not an advanced devotee, and I am full of faults. Yet the subject matter of which I write is perfect and pure, and will benefit the sincere reader just as fire will purify gold. Whether that fire is lit by a low-class caṇḍāla or a high-class brāhmaṇa, the action of purification will be the same.

There is another question or objection that devotees raise when they hear of newly published rasika books entering the mainstream of devotees.

“Would not the publishing of a book of confidential subject matter risk leading immature iskcon devotees into the troubled waters of inappropriate conduct, or worse, deviation?”

My answer is,

“Unfortunately, we should expect that in our age the abuse of good things is inevitable. But should we deprive sincere Vaiṣṇavas of inspiration just because some deviants are set on degradation?

“I say ‘No!’”

Caitanya Mahāprabhu came to distribute the most sacred mellow of conjugal love. And while the Lord’s gift was appropriately worshipped by his faithful followers, it was also distorted by pseudodevotees who founded a host of deviant sects that continue to this day. Similarly, ācāryas like Rūpa Gosvāmī wrote many books to educate and inspire devotees in the ways of pure love, but over the

centuries these books were misused to fuel the ongoing practice of sahajiyās.

Śrīla Prabhupāda introduced Kṛṣṇa consciousness to the world, and despite his own guarded approach in the presentation of confidential subjects, still his teachings found their way into the hands of unscrupulous people who took to the ranks of apa-sampradāyas.

done!

It is inevitable that when something of inestimable value is distributed for the benefit of those who are honest, it will be misused by those poisoned by sense gratification and desires for liberation.

Knowing this risk, the Lord and his representatives continue to teach the world, and in that way they fulfil their mission in delivering those of saintly character.

I shall further add that the mission of delivering even the saintly is not one that meets with immediate success. It may take multiple lifetimes for practising devotees to attain perfection. Kṛṣṇa himself points out that the percentage of saintly souls who immediately perfect his gift of transcendental knowledge is small. And yet for a few souls, he takes the risk that his teachings may be distorted:

manuṣyāṇāṁ sahasreṣu kaścid yatati siddhaye yatatām api siddhānāṁ kaścin māṁ vetti tattvataḥ

Out of many thousands among men, one may endeavour for perfection, and of those who have achieved perfection, hardly one knows me in truth.8

In the same way, since writing transcendental literature is our family business and the order of Śrīla Prabhupāda, I do not feel it justifiable that I should refrain from serving honest Vaiṣṇavas simply because some rascals will use my books as kindling for the fire of their misconceptions.

Thus, once again I reply to the question, “Unfortunately, we should expect that in our age the abuse of good things is inevitable. But should we deprive sincere Vaiṣṇavas of inspiration, just because some deviants are set on degradation?

“I say ‘No!’”

In conclusion, let me add that the Vai ṣṇ ava marketplace is awash with translations and commentaries of confidential topics. Furthermore, the internet is equally inundated with conferences in which uninitiated, unsupervised, and clearly unqualified neophytes take part in every variety of esoterica. As a result, devotees are exposed to many dangers, not least of which is the reality that they stray from their gurus, from iskcon, and from the path of Rūpa and Raghunātha that Śrīla Prabhupāda so expertly paved for his sincere followers.

My whole purpose in writing the Kṛṣṇa in Vṛndāvana series was to o er to devotees who are eager for k ṛṣṇ a-kath ā the opportunity to hear those topics in Śrīla Prabhupāda’s line. I want to show that Ś r ī la Prabhup ā da did give devotees the complete process of perfection. I want to show that in iskcon today, that path of perfection is alive and well, trod by genuine devotees with a sincere determination to reach its destination. I want to o er literature that is an alternative to the unprotected marketplace. I want to o er literature that will keep devotees in Ś r ī la Prabhup ā da’s fold and fully aware that we walk the path of Kṛṣṇa consciousness by his mercy alone.

This is the reasoning upon which I have published Vil ā pakusumāñjali. I rest my case before my readers.

While following Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī and Rati-mañjarī, I have done my best to express the truths of r ā g ā nuga-s ā dhana according to the way of Vilāpa-kusumāñjali. If there is any mistake in this work, it is obviously my shortcoming, hence I beg the Vaiṣṇavas for their forgiveness. May the devotees of the Lord bless me to complete this undertaking. I am truly hopeful that if readers lend this Vilāpa-kusumāñjali a submissive ear, they will be spiritually benefitted, and thus my e ort will be doubly rewarding—for me, and for them.

n this section I address a few stylistic techniques that I have employed in Vilāpa-kusumāñjali, techniques different from or in addition to those I have used in other books. Since the literary styles in earlier works have already been explained, they require no further commentary here.

That said, there is one literary device that I have substantiated in earlier books and which I shall now explain further: it is the device of dialogue, a device that I employ to convey devotional moods, truths, and pastimes. These dialogues take up a substantial part of the commentaries and are very much my realisations. Thus they may well be the subject of scrutiny for inquisitive minds.

The most glaring aspect of dialogue that gives rise to objections is that I am seen to be putting words in the mouths of Vil ā pakusum ā ñjali’s characters: Raghun ā tha D ā sa Gosv ā m ī , Ratimañjarī, Śrīmatī Rādhārāṇī, Kṛṣṇa, other gopīs, and so on. Since the reader has not yet entered the book, I give an example of dialogue between Raghun ā tha D ā sa Gosv ā m ī and Ś r ī R ā dh ā , from Verse Thirty-one of Volume Two.

What Caitanya Mah ā prabhu had intimated has now come to pass. Raghunātha Dāsa has lived by the foot of Govardhana Hill in Rādhā-kuṇḍa, and he has attained the shelter of Rādhā’s lotus feet. And while the prophecy of his residence is factual, Rādhā’s service is not. At least that is the way he sees it. Being a servant is a permanent position. But his service to Rādhā seems to be occasional—sometimes he is Rati-mañjar ī , sometimes the mahānta of Rādhā-kuṇḍa. Thus he thinks to himself,

“When will Caitanya Mah ā prabhu’s prophecy come to pass?”

But according to Rādhā it has come to pass. She says,

“You always enjoy my shelter and my service. Why think otherwise?”

Dāsa Gosvāmī understands.

“You mean sometimes I serve your lake and servants, and sometimes I serve you directly.”

“Both are direct service to me, but in di erent forms— as lake, and as gopī. ”

Reluctantly he nods,

“But surely one may have a preference? You, too, see Kṛṣṇa in dream and in person. Yet you prefer serving him in person.”

Now it is Rādhā’s turn to nod.

“You are right. But just as it is inevitable that I dream, it is inevitable that you serve the mission of Rūpa and Caitanya Mahāprabhu.”

She adds,

“At least as long as you are in this body of a sādhaka.”

Again he reluctantly nods in assent. It seems that as long as he is in this world, Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī must continue to oscillate between these two kinds of service to Rādhā. Only when he has left the world of mortals for Goloka will his service of preference be realised.

Am I putting words in the mouths of the ācārya and Rādhā?

Yes I am.

Not because I am taking dictation from the transcendental realm, but because I am employing poetic licence, which offers writers the freedom to use di erent techniques in order to achieve a desired e ect.

That answer may be a hard pill to swallow for some readers. Hence I will sweeten it with the support of a detailed explanation that takes the form of answers to five main questions that my methodology gives rise to. Those questions are:

What are you doing?

Why are you doing it?

Are you, as a conditioned soul, qualified to do it?

On what precedent and authority do you base your writing?

While there may be precedent, do you have the eligibility of your predecessors?

We start with the first question, which is, “What are you doing?”

Throughout Vil ā pa-kusum ā ñjali, especially Volume Two onwards, I have included conversations between the characters referred to in the verses. Their conversations are almost exclusively my realisation, written as a means to further add context to the narrative of Dāsa Gosvāmī ’s verses, and to establish the voice and tone of the book. Moreover, the dialogues provide a natural foundation to define the characters and storylines, while providing a smooth transition for changes of direction between successive verses.

The content of the dialogue directly and indirectly reveals truths regarding both mellows and philosophy. It is further interspersed with pastimes relevant to the aforementioned truths, or to pastimes explicitly described by the verses. However, the most relishable aspect of these talks is the mood that they generate between the characters, thus revealing the loving, friendly, humorous interactions among the Vraja-vāsīs.

If readers are not attentive, the casual exchanges among the characters of Vilāpa-kusumāñjali can be misleading. Dialogues do not always mean what they say; in other words, they have indirect meanings. Humour and innuendo often conceal another meaning, in a language known as parokṣa-vāda:

parokṣa-vādā ṛṣayaḥ parokṣaṁ mama ca priyam

The Vedic seers and mantras deal in esoteric terms, and I also am pleased by such confidential descriptions.9

The indirect meanings are sometimes revealed by my comments, at other times they are left to the reader’s fine discretion to decipher. The concealed meanings of the verbal exchanges can be detected when the direct meaning is not consistent with the ongoing theme. These are some of the purposes of the dialogues found in the commentaries, and the answer to the question, “What are you doing?”

The second and obvious question follows from the first, “Why are you doing it?”

One of the primary reasons is that dialogue makes the subject matter more attractive. Conversations o er the same content as philosophy, but in a form that facilitates reader attention. Hence devotees eagerly read a book that they would otherwise struggle with and perhaps abandon.

The conversations are entertaining in a pure and transcendental way, o ering an experience rather than a description of the interaction between Kṛṣṇa and his associates. In other words, conversations give a taste of the sweetness of the love between the characters of the book.

One very personal reason for this approach to writing is my inspiration to do it. That inspiration was partly my own personal attraction to the style, and partly my conviction that this was sanctioned by Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī.

How do I know what the ācārya sanctioned?

The short answer is: because I felt it.

The longer answer is: the very definition of inspiration is an

inner stimulus to think or to do something in a certain way. Since inspiration is a subjective experience, the conviction I had that I was experiencing Dāsa Gosvāmī ’s guidance cannot be feelingly transmitted to others. It can only be expressed in its reflection, which is the limited form of words. And the most succinct form those words take is, “because I felt it.”

In commenting on Vilāpa-kusumāñjali, I had to continually pray to the author for guidance and correction. That guidance often came in a modest way, such as in the proper choice of a word. Sometimes guidance came in a more significant way, like the most suitable manner to elaborate upon a suggestive metaphor such as, “your hips, the sacred pilgrimage place of Lord Kṛṣṇa.”10

Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī ’s guidance also confirmed my predisposition to constructing commentaries from a combination of narrative and dialogue. In the Nava-vraja-mahim ā version of Vilāpa-kusumāñjali, I had already included short dialogues which I and readers relished as the sweetest part of the exegesis. In this elaborate edition I felt a more detailed commentary was needed, and that, too, was confirmed from within.

As a final point on my sources of inspiration, I should add that one’s own feelings and inspiration should conform to the precedent of scripture and ā c ā ryas. When answering the fourth objection, “On what precedent and authority do I base my writing?”, I shall show that the dialogue style in my commentary is common to both śāstra and to works of the ācāryas.

I now conclude, with two final reasons, why I chose to include the conversational style in the commentaries.

One is that some verses beg for elaboration in the form of a verbal exchange, such as the following:

O Svarṇa-gaurī! Golden girl! When will you order me to place an armband of nine jewels upon your left arm, and then carefully tie it with a decorative string beautified with silken tassels.11

In this verse the author prays for R ā dh ā to give an instruction. Describing that pastime necessitates a conversation in which Rādhā says,

“Rati! Tie the nava-ratna armband on my left arm.”

Thereafter Rati explains what the armband is like and what it does.

“The nine gems will ward o all inauspicious elements that may obstruct your meeting with Kṛṣṇa.”

To which Rādhā will respond, and a dialogue will ensue.

The second reason for this conversational style is due to the existing pastime that the verse or the commentary refers to.

For example, Verse Sixty-five describes Mother Yaśodā’s morning farewell to Kṛṣṇa when he takes the cows to the forest. Books like Bṛhad-bhāgavatāmṛta and Govinda-līlāmṛta, among others, detail conversations between mother and son. Commenting on this verse will certainly necessitate quoting from and paraphrasing those talks, which then results in an enchanting dialogue that reflects the intricacies of parental love.

move on to the third objection: “Are you, as a conditioned soul, qualified for this kind of transcendental dialogue?” Both the question and its answer are similar to and completed by the response to the upcoming question five. But the repetition is required, because the qualification of the author is the main criteria for what he writes. If an author is of the unquestionable stature of Rūpa Gosvāmī or Veda-vyāsa, no one questions what they write. If the author is Śivarāma Swami, then they do.

However, there is an inherent defect in the question in that it assumes Śivarāma Swami is a conditioned soul—which he is. The defect is that it is rare for authors to declare themselves liberated souls. They say they are fallen, conditioned souls. And yet they still write on many subjects of transcendence.

Śrīla Prabhupāda would say,

A liberated soul never says that “I am liberated.” As soon as he says “liberated,” he is a rascal. A liberated soul will never say that “I am liberated.”12

Similarly, in the Introduction to Vidagdha-m ā dhava, R ū pa Gosvāmī wrote,

I am by nature ignorant and low… although I am very low by nature.13

And in Caitanya-caritāmṛta the author writes,

jagāi mādhāi haite muñi se pāpiṣṭha purīṣera kīṭa haite muñi se laghiṣṭha mora nāma śune yei tāra puṇya kṣaya mora nāma laya yei tāra pāpa haya

I am more sinful than Jag ā i and M ā dh ā i, and even lower than the worms in the stool. Anyone who hears my name loses the results of his pious activities, anyone who utters my name becomes sinful.14

Indeed, His Divine Grace would often give Caitanya Mahāprabhu as an example in which God himself admits that he is a fool before his guru.

While ācāryas all take a humble position in their writings, their claim to authenticity is not their liberated status—bhāva, prema, or mahā-bhāva. Their authenticity lies in that they are following their liberated predecessors and scripture. Even Kṛṣṇa establishes the authority for his teachings by referring to liberated sages and the Vedānta:

ṛṣibhir bahudhā gītaṁ

chandobhir vividhaiḥ pṛthak brahma-sūtra-padaiś caiva hetumadbhir viniścitaiḥ

That knowledge of the field of activities and of the knower of activities is described by various sages in various Vedic writings. It is especially presented in Vedānta-sūtra with all reasoning as to cause and e ect.15

The qualification of being a follower is exemplified by the eternally liberated Kavir ā ja Gosv ā m ī . In composing Caitanya-carit ā m ṛ ta , the ācārya repeatedly claims to be following in the footsteps of his

predecessor, Vṛndāvana Dāsa Ṭhākura, the incarnation of Vyāsa and the author of an earlier biography on Caitanya Mahāprabhu, now known as Caitanya-bhāgavata. He writes,

Actually the authorised compiler of the pastimes of Śrī

Caitanya Mah ā prabhu is Ś r ī la Vṛ nd ā vana D ā sa, the incarnation of Vy ā sadeva. Only upon his orders am I trying to chew the remnants of food that he has left.16

Similarly, my spiritual status is not the qualification for composing dialogue among the characters of Vilāpa-kusumāñjali. My qualification is that I follow s ā dhu, guru, and śā stra. Whether I am a conditioned soul or not is beside the point. None of my predecessors made it a point when introducing their books. I may be conditioned. I may be liberated. Regardless, I explicitly follow the perfect—sādhu, guru, and śāstra.

Thus, Vai ṣṇ avas kind enough to examine me and my writing should see whether I am following my predecessors. If they examine me with an open mind, I am sure that they will be convinced of the validity and authenticity of not only the dialogues, but of the entire commentary to this great work of Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī.

The paragraph above naturally begs the next enquiry, question four: “What is the precedent and authority for your dialogues?”

This enquiry really points to the heart of the matter, and is a most welcome challenge. Hopefully the answer will be similarly welcomed by the reader.

In support of the dialogue style, I will cite the methodology of sm ṛ ti in general, Caitanya Mah ā prabhu, Vi ś van ā tha Cakravart ī Ṭ h ā kura, Baladeva Vidy ā bh ūṣ a ṇ a, a Bh ā gavatam commentator named Harisūri, and Śrīla Prabhupāda.

I shall begin this answer by citing Ś r ī la Prabhup ā da’s wellknown definition of “realisation,” which is how I refer to my Vilāpa-kusumāñjali dialogues. They are my realisations.

Personal realisation does not mean that one should, out of vanity, attempt to show one’s own learning by trying to surpass the previous ācārya. He must have full confidence in the previous ācārya, and at the same time

he must realise the subject matter so nicely that he can present the matter for the particular circumstances in a suitable manner. The original purpose of the text must be maintained. No obscure meaning should be screwed out of it, yet it should be presented in an interesting manner for the understanding of the audience. This is called realisation.17

A full study of this purport lends itself to a book, something we will not undertake. Yet Ś r ī la Prabhup ā da’s message is loud and clear.

The qualification of an author is freedom from personal motivation, and faith in and fidelity to his predecessors and scripture.

His freedom in expressing his realisation is based upon circumstances, suitability of the subject matter, and a presentation that interests and educates his audience.

In the conversations found in this book, I believe that I have been true to Śrīla Prabhupāda’s licence in expressing my realisations on Vilāpa-kusumāñjali.

How have I fulfilled Śrīla Prabhupāda’s criteria?

I have already explained that the availability of rasika books and the temptations o ered by teachers outside iskcon establish a circumstance in which commentaries on books like Vilāpakusum ā ñjali within iskcon are a necessity. Ś r ī la Prabhup ā da’s line should set the gold standard for such literature, as was the case with the bbt ’s publication of B ṛ had-bh ā gavat ā m ṛ ta. Therefore, I have presented the dialogues in a way I believe will enhance the attractiveness and readability of this well-known and well-read book.

Furthermore, I have attempted to present the verses of Vil ā pa-kusum ā ñjali in the same innocent language that Ś r ī la Prabhu p ā da presented gop ī -l ī l ā in K ṛṣṇ a Book . The dialogues help make the subject matter of D ā sa Gosv ā m ī ’s verses suitable to a wide audience, while remaining faithful to the original author’s intent.

Finally, dialogues not only o er a breather from philosophical narratives or Vraja pastimes, but also interest the reader and communicate e ectively to the audience.

I have briefly argued how my dialogue-realisations satisfy Śrīla Prabhupāda’s criteria of a realisation, and so shall turn my attention to explaining what the precedents are for this work.

I begin with the composition of itihāsas as a means of explaining Vedic knowledge.

Vedic literature has two divisions, ś ruti and sm ṛ ti, “what has been heard” and “what has been remembered,” respectively. The former are scriptures received in meditation by sages, passed down to learned br ā hma ṇ as in an unbroken chain of disciplic succession. The latter are composed by sages who uphold the message of śruti without repeating the same wording, and with the purpose of uplifting the common man.

Part of smṛti are the Itihāsas, most outstanding of which are the Rāmāyaṇa and Mahābhārata, and the Purāṇas. The special feature of these texts is that they are written in simplified Sanskrit with the purpose of transmitting the essence of the Vedas through captivating historical narratives.

The prime example among the Purāṇas is Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam, which presents for easy understanding the message of the Vedas in language, format, histories, and dialogues not found in the original texts upon which it comments. Indeed, Caitanya Mahāprabhu says Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam is the commentary on Brahma-sūtra and the Upaniṣads, and the Garuḍa Purāṇa says,

artho ’yaṁ brahma-sūtrāṇām

The meaning of the Vedānta-sūtra is present in ŚrīmadBhāgavatam. 18

It is noteworthy to compare Vedānta-sūtra, a book of philosophical codes, with Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam, a book of philosophy, pastimes, and dialogue. By making such a comparison it is clear that while the philosophical essence of the two is the same, their method of presentation is very di erent. And part of Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam’s presentation is extensive dialogues. In this way sm ṛ ti uses the device of dialogue to explain śruti.

Similarly, for ease of comprehension, I have commented with narrative and dialogue on the original verses of Raghunātha Dāsa

Gosv ā m ī . That commentary may appear di erent, yet following Śrīla Prabhupāda’s definition of realisation and the methodology of the Vedas, it is authentic.

shall now cite Caitanya Mahāprabhu’s example. Before doing so, I place the dust of his lotus feet on my head and beg forgiveness for any inaccuracies I may make in my reference to him.

Throughout Caitanya-caritāmṛta, the Lord elaborates on verses from śāstra, mostly Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam, and these elaborations are often in the form of dialogues. The following is an example that took place in the Gambhīrā when the Lord wanted to hear from Rāmānanda Rāya about the nectar of Kṛṣṇa’s lips. His servant complied, and spoke the following verse:

gopyaḥ kim ācarad ayaṁ kuśalaṁ sma veṇur dāmodarādhara-sudhām api gopikānām bhuṅkte svayaṁ yad avaśiṣṭa-rasaṁ hradinyo hṛṣyat-tvaco ’śru mumucus taravo yathāryāḥ

My dear gop ī s , what auspicious activities must the flute have performed to enjoy the nectar of Kṛṣṇa’s lips independently and leave only a taste for us gopīs, for whom that nectar is actually meant. The forefathers of the flute, the bamboo trees, shed tears of pleasure. His mother, the river on whose bank the bamboo was born, feels jubilation, and therefore her blooming lotus flowers are standing like hair on her body.19

Thereafter Kavirāja Gosvāmī writes,

Upon hearing the recitation of this verse, Śrī Caitanya Mah ā prabhu became absorbed in ecstatic love, and with a greatly agitated mind he began to explain its meaning like a madman.

I quote only a few of the many verses of dialogue Caitanya Mahāprabhu speaks:

Some gopīs said to other gopīs, “Just see the astonishing pastimes of Kṛṣṇa, the son of Vrajendra! He will certainly marry all the gopīs of Vṛndāvana. Therefore the gopīs know for certain that the nectar of Kṛṣṇa’s lips is their own property and cannot be enjoyed by anyone else.

“My dear gopīs, fully consider how many pious activities this flute performed in his past life. We do not know what places of pilgrimage he visited, what austerities he performed, or what perfect mantra he chanted.

“This flute is utterly unfit because it is merely a dead bamboo stick. Moreover, it belongs to the male sex. Yet this flute is always drinking the nectar of Kṛṣṇa’s lips, which surpasses nectarean sweetness of every description. Only by hoping for that nectar do the gopīs continue to live.

“Although the nectar of K ṛṣṇ a’s lips is the absolute property of the gopīs, the flute, which is just an insignificant stick, is forcibly drinking that nectar and loudly inviting the gopīs to come drink it also. Just imagine the strength of the flute’s austerities and good fortune! Even great devotees drink the nectar of Kṛṣṇa’s lips after the flute has done so.”20

This is not isolated dialogue. From the beginning of the Madhya-līlā to the end of the Antya-līlā, the Lord’s biography is replete with elaborations in the same format. Of course, Caitanya Mahāprabhu’s authority surpasses that of anyone and anything. It is absolute! But that does not restrict me from following him. To the contrary, his example lends authority to my doing so. Moreover, we should consider Kṛṣṇadāsa Kavirāja’s statement on the sources of the Lord’s words recorded in his book.

He says that they were originally documented in the notebooks of Svarūpa Dāmodara and Raghunātha Dāsa. He simply had access to those notebooks. Either he read them or heard their contents from Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī. He was never in Purī personally, and he never heard or saw Caitanya Mahāprabhu. Yet he asserts that his rendering was even more elaborate than what the two Gosvāmīs wrote:

svarūpa—‘sūtra-kartā’, raghunātha—‘vṛttikāra’ tāra bāhulya varṇi—pāṅji-ṭīkā-vyavahāra

Svarūpa Dāmodara wrote short notes, whereas Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī wrote elaborate descriptions. I shall now describe Śrī Caitanya Mahāprabhu’s activities more elaborately, as if flu ng out compressed cotton.21

Thus it is doubtful whether the dialogues Caitanya Mahāprabhu speaks in his biography are a verbatim rendition. Rather, they were the author’s further expression of what the two great ācāryas wrote. They were Kṛṣṇadāsa Kavirāja’s words.

This means that Kṛṣṇadāsa Kavirāja approved of the device of dialogue, and he himself composed sentences and verses that his book and its readers attribute to Lord Caitanya. He was furthering the Lord’s dialogue.

I find that both the Lord’s speeches of divine madness and his biographer’s elaborations are further confirmation of the literary practice I have employed.

Next I shall cite Vi ś van ā tha Cakravart ī Ṭ h ā kura, who makes extensive use of dialogue throughout his commentaries, such as in the Tenth Canto of Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam. However, the example I quote is from the ācārya’s Sārārtha-varṣiṇī-ṭīkā commentary to the Bhagavad-gītā, in which he uses dialogue, along with narrative, throughout his gloss of the text. In Chapter Nine, Verses Thirty and Thirty-one, Cakravartī Ṭhākura comments thus:

api cet sudurācāro bhajate mām ananya-bhāk sādhur eva sa mantavyaḥ samyag vyavasito hi saḥ

Even if one commits the most abominable action, if he is engaged in devotional service, he is to be considered saintly because he is properly situated in his determination.22

Now begins the dialogue-commentary.

[K ṛṣṇ a] “My nature is to be attached to my devotee, and that attachment does not wane even if my devotee is a sinner. Be he of bad conduct, violent habits, a thief, or adulterer, if he worships me and me alone, ignoring both karma and jñ ā na , with no desire other than to please me, that person is my devotee, a sādhu whom I quickly raise to the highest standard of pure devotion.”

[Arjuna] “But in consideration of his bad conduct, how is such a person a devotee?”

[Kṛṣṇa] “His devotional qualities are what define him as a devotee and make him respectable. That is my decree. I am the ultimate authority on dharma and bhakti, and ignoring my conclusion on this matter is an o ence.”

[Arjuna] “That means he should be considered a devotee to the degree that he worships you, and as a non-devotee to the degree that he sins.”

[Kṛṣṇa] “No! He should be considered a complete devotee always, and you should disregard his faults altogether. Because of his firm conviction, such a devotee, although fallen, will have this sincere resolve: ‘I may go to hell for my sins and for my attachment to them, but never will I abandon service to my Lord.’”

[VCT] Kṛṣṇa then speaks the next verse:

kṣipraṁ bhavati dharmātmā śaśvac-chāntiṁ nigacchati kaunteya pratijānīhi na me bhaktaḥ praṇaśyati

“He quickly becomes righteous and attains lasting peace. O son of Kuntī, declare it boldly that my devotee never perishes.”23

[Arjuna] “How can you accept the worship of such a sinful person, or eat the food and drink the water o ered by a heart contaminated by lust and anger?”

[K ṛṣṇ a] “Because that person quickly becomes righteous.”

[VCT] This sentence is notably in the present tense, not future, which implies that having sinned, if a devotee remembers Kṛṣṇa and repents, he is immediately purified.

The devotee laments in this way: “What an unfortunate sinner am I! I am so fallen that I have smeared the good name of the Vaiṣṇavas.” Over and over again, the devotee feels complete disgust for his past acts.

The present tense can also indicate that although the devotee will fully develop righteousness in the future, it exists in him now, but in a subtle form.

For example, after taking medicine, the e ects of fever or disease remain for some time, but because the patient will soon be cured, the residue symptoms of illness are not considered to be serious. Similarly, as bhakti enters a devotee’s mind, his past sinful actions are irrelevant, and every trace of lust and anger are as insignificant as the bite of a toothless snake. In this way a devotee attains complete and lasting freedom from his

bad qualities. In the word nigacchati, “ni” is nitarām, “completely,” which means that even while his tendency to commit sin remains, his heart is pure.

[Arjuna] “I can accept that he becomes righteous in time, but if he is sinful until death, what is his position?”

[VCT] The Lord, who is a ectionate to his devotees, speaks loudly and with some anger:

[K ṛṣṇ a] “O son of Kunt ī ! My devotee is never vanquished! Even at the time of death he does not become fallen.”

[Arjuna] “But critical people will neither accept nor respect your argument.”

[VCT] Seeing that Arjuna is concerned for his Lord’s reputation, Kṛṣṇa encourages him.

[K ṛṣṇ a] “Listen to me, Kaunteya! Beating a drum to the heavens, march boldly into the assembly of those squabblers and before their very eyes throw your hands in the air and fearlessly declare this!”

[Arjuna] “Declare what?”

[K ṛṣṇ a] “Declare that my devotee, the devotee of the Supreme Lord, although a sinner, does not perish, but rather he reaches supreme perfection. When you defeat their arguments and deflate their pride, they will accept you as their guru.”

[VCT] The following is Śrīdhara Svāmī ’s explanation of Kṛṣṇa’s declaration:

[SS] And why does the Lord order Arjuna to make such a declaration when he could do it himself? It isn’t that he does not make personal declarations, such as when

he says, m ā m evai ṣ yasi satya ṁ te pratij ā ne priyo ’si me, “I promise you this because you are my very dear friend.” So why does he not say, “Kaunteya! I now declare that my devotee never perishes”?

The reason will now be explained.

Kṛṣṇa thought in this way,

[Kṛṣṇa] “Because I am very a ectionate to my devotees, I cannot tolerate even the slightest criticism of them. Therefore whatever my devotees say, I uphold under all circumstances. By contrast I can break my own promise and accept the resulting criticism, just as I broke my own promise by fighting with Bhīṣma, in order to uphold his promise.

“As a result of such conduct of mine, some people have lost faith in my promise, and if I declare the glories of devotees, philosophical wranglers will laugh and ignore me. But if Arjuna makes such a proclamation, even the most pessimistic jñānī will take my friend’s words as if engraved in stone. Therefore, I will insist that Arjuna makes this declaration in my place.

“But if, after hearing from the mouth of my pure devotee, some fools continue to doubt the power of undeviating devotion in even the greatest sinner, those doubters should be ignored. Unfortunate are they who do not know that Arjuna’s declaration applies even in cases where devotees still struggle with attachment to wife, children, sinful acts, lamentation, illusion, lust, anger, and other despicable qualities. But the truth is that whatever the shortcoming, my devotee quickly becomes righteous.”

The dialogue exchange above is not unique to the ācārya’s commentaries; rather, it is standard. However, this exchange is not part of the original G ī t ā text. So where does it come from? Is it the

revelation of some longer version of the book? The ācārya makes no such mention. What he does write in the introductory verses is that his commentary—implying, dialogue included—is a product of his own construct of previous commentaries and Caitanya Mahāprabhu’s teachings. He writes,

prācīna-vācaḥ suvicārya so ’ham ajño ’pi gītā mṛta-leśa-lipsuḥ yateḥ prabhor eva mate tad atra santaḥ kṣamadhvaṁ śaraṇāgatasya

Although I am ignorant, after carefully considering the previous commentaries, I desired to obtain a drop of the nectar of the Gītā and have thus composed this commentary. May the devotees tolerate the work of a surrendered soul, which he has written according to the conclusions of his sannyāsī master, Śrī Kṛṣṇa Caitanya.24

Here we have the example of a most exalted commentator and ācārya, one whom Śrīla Prabhupāda consulted most frequently in composing his own Bh ā gavatam commentaries. The very meaning of ācārya is one who teaches by his personal example. Is his method of composing commentary with dialogues not an example to follow? Nowhere does Cakravartī Ṭhākura exclude his readers from following the stylistic example he sets. Thus the natural and direct implication of his extensive dialogues, like those of Caitanya Mahāprabhu and Kavirāja Gosvāmī, is that others who study the commentaries of previous ācāryas and understand the teachings of Caitanya Mah ā prabhu may use the same conversational style in their commentaries.

f the other preceptors I have mentioned earlier, namely Baladeva Vidyābhūṣaṇa, Śrīla Prabhupāda, and Harisūri, none of them, nor any other ā c ā rya I have come across in my studies, claim exclusivity to their literary style. Rather than simply apply the reasoning of Cakravartī Ṭhākura to

these three ācāryas, I shall give examples of how they, too, use dialogue in their writings to elaborate on original works.

A commentary ascribed to Baladeva Vidy ā bh ūṣ a ṇ a (a contemporary of Vi ś van ā tha Cakravart ī Ṭ h ā kura) on Raghun ā tha D ā sa Gosv ā m ī ’s prayer to Govardhana Hill known as Govardhana-v ā sa-pr ā rthan ā -da ś aka , also employs the conversational style.25 I will show the dialogue through the poem’s first three verses:

nija-pati-bhuja-daṇḍac-chatra-bhāvaṁ prapadya pratihata-mada-dhṛṣṭoddaṇḍa-devendra-garva atula-pṛthula-śaila-śreṇi-bhūpa priyaṁ me nija-nikaṭa-nivāsaṁ dehi govardhana tvam

O Govardhana! O king of all incomparable great mountains who became an umbrella in the hand of Lord Kṛṣṇa and so destroyed the pride of the deva-king who madly attacked you with raised weapons, please grant the residence near you that is so dear to me.26

After the introduction to the first verse, Ś r ī Baladeva presents a conversation between Dāsa Gosvāmī and Govardhana Hill:

[RDG] “O Govardhana! Since you are so dear to me, please attract my mind away from any other holy place and let it be fixed upon you. Please, O please, grant me residence near you.”

[Govardhana] “There are many hills nearby. Why would you want to abandon living near them for exclusive residence near me?”

[RDG] “Because you are the king of all mountains, overflowing with incomparable, divine qualities that are matched only by your incomparable width.”

[Govardhana] “O s ā dhu ! It is well known that you desire to be a Vraja-vāsī, so take up residence anywhere

in Vraja-maṇḍala. What will you gain by living exclusively by my side?”

[RDG] “Since no one can compare to you, no one can shelter me like you. Who else but you transformed into an umbrella upon the handle-arm of K ṛṣṇ a, and so humbled pride-intoxicated Indra, while sheltering the Vraja-vāsīs.”

The conversation continues in the commentary to the second verse:

[Govardhana] “The prayer in the previous verse was certainly complimentary, and so I o er you the chance to reside beside me for two or three days, but why would you want to live here forever?”

[RDG] “The eternally youthful couple, Rādhā-Kṛṣṇa, enjoy wonderfully intoxicating amorous pastimes in your caves. Being desirous of always witnessing their sports, I seek eternal residence here, and not just for a few days.”

And it continues in the third verse:

[Govardhana] “Why not reside near Sa ṅ keta-vana, where I am sure that you will also see many divine pastimes of the youthful couple, after which your heart yearns. You do not need to pray for residence near me.”

[RDG] “O Govardhana Hill! When living near you I see not only the pastimes of the divine couple, but the pastimes of Kṛṣṇa and the gopas. The gopas often come here because you arrange pastime-places for Kṛṣṇa and Balar ā ma with your jewel-bedecked thrones, waterfalls, and caves, as well as the sweet grasses for cows. O great hill! Please do not deny me residence.”

The conversation continues in this way throughout the ten verses of the prayer. Once again, this conversation was not composed

by Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī, and yet, two hundred years later, Baladeva Vidyābhūṣaṇa uses the device of dialogue as a means of commentary.

I found Ś r ī Baladeva’s example particularly important since, like mine, his is a commentary on a work by Raghun ā tha D ā sa Gosv ā m ī . Thus I find further confirmation that this kind of literary device is but another way of speaking tattva and l ī l ā simultaneously.

Let me pause here to elaborate on the last sentence above by asking, “What does a devotee do when he lectures or teaches?” Take the example of a lecturer explaining Rūpa Gosvāmī ’s definition of pure devotional service, which begins with anyābhilāṣitā-śūnyam.

When elaborating on this verse, a lecturer paraphrases, giving in their own words and from their own realisations a more elaborate or extensive explanation of the ācārya’s teachings. While not quoting verbatim, the lecturer is, nonetheless, giving the essence of Rūpa Gosvāmī ’s words. In other words, a devotee intimates, “This is what Rūpa Gosvāmī says and means.” As a result, the explanation of Rūpa Gosvāmī ’s śloka—including examples, quotes, and more—is to put words in Rūpa Gosvāmī ’s mouth. This example is no di erent from what I do in conversations between the characters of Vilāpa-kusumāñjali.

That said, I shall now return to show how Ś r ī la Prabhup ā da encouraged and exemplified the expression of personal realisations.

It is important to note how much Śrīla Prabhupāda desired that his disciples write their realisations in the form of philosophy and pastimes, both in his Back to Godhead and in their own books. His Divine Grace considered that a strict sādhaka, matured by service, can be empowered and directed by K ṛṣṇ a to compose transcendental literature. The following are a few of the many quotes that paint a picture of Śrīla Prabhupāda’s expectations from his disciples, as per their literary output.

His Divine Grace expected that after reading his books, his disciples would be inspired to write; indeed, he expected it:

All students should be encouraged to write some article after reading Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam, Bhagavad-gītā, and Teachings of Lord Caitanya. They should realise the

information, and they must present their assimilation in their own words. Otherwise, how they can be preachers?27

And he also encouraged devotees to write poetry and even bhajans:

You can utilise your propensity to write poems and articles for BTG, for singing in the kīrtana, like that. That will make you very happy.28

Ś r ī la Prabhup ā da equated spiritual realisation with writing, and writing with meditation, smaraṇam:

Realisation means you should write. Every one of you. What is your realisation…what you have realised about K ṛṣṇ a. That is required…Writing or o ering prayers, glories—this is one of the functions of the Vaiṣṇava… writing means smaraṇam—remembering what you have heard from your spiritual master.29

When a pure devotee writes of Kṛṣṇa’s pastimes, he receives guidance directly from Kṛṣṇa:

Transcendental literature that strictly follows the Vedic principles and the conclusion of the Purāṇas and Pāñcarātrikī-vidhi can be written only by a pure devotee…Since a devotee writes in service to the Lord, the Lord from within gives him so much intelligence that the devotee sits down near the Lord and goes on writing books.30

Finally, a devotee receives permission to write from the spiritual master—which Ś r ī la Prabhup ā da has given in his many instructions—and from Kṛṣṇa within the heart.

One must first become a pure devotee by following the strict regulative principles and chanting sixteen rounds daily, and when one thinks that he is actually on the

Vaiṣṇava platform, he must then take permission from the spiritual master, and that permission must also be confirmed by Kṛṣṇa from within his heart. Then, if one is very sincere and pure, he can write transcendental literature, either prose or poetry.31

While Śrīla Prabhupāda freely makes use of dialogue in his commentaries and talks, it is always very short, and so I will not quote any here. However, I believe that the quotes above give leeway for a wide variety of literary styles with which devotees may express realisations and compose literature—“either prose or poetry.”

My closing example is of an ā c ā rya in the line of Tuk ā r ā ma’s saṅkīrtana succession, Harisūri. In using this example I move out of the Gauḍīya line just to show that the initiative of realisation and dialogue is found among other authentic Vaiṣṇava traditions close to ours.

Harisūri was born in 1810 in a Mahārāṣṭran brāhmaṇa family, and in the maturity of his Kṛṣṇa consciousness, Kṛṣṇa requested him to write a Tenth Canto commentary to explain the reasons behind each and every one of the Lord’s pastimes.

Harisūri did as requested, and in a book called Bhakti-rasāyanam, published by his son at the end of the nineteenth century, the author commented on the thirty-nine chapters of Kṛṣṇa’s Vṛndāvana pastimes, giving reasons for why Kṛṣṇa acts the way he does.

The relevant feature of that book is that both in the form of narrative and dialogue, Harisūri describes the reasoning and motive behind the pastimes recorded in Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam.

One example is from the brahma-vimohana-līlā.

When Brahm ā stole the calves, K ṛṣṇ a reassured his anxious friends, who were lunching, and went o in search of the calves. Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam says that Kṛṣṇa left the gopas while holding cooked rice in his fist, sapāṇi-kavalo yayau.32

Harisūri asks,

Why did Kṛṣṇa keep the cooked rice in his hand?

The ācārya’s answer is based on the dual meaning of the word bhakta, which may be either “devotee” or “cooked rice.” Thus he writes,

sarvaṁ tyajāmi samaye bahunā kiṁ priyām api sadāśaya-gataṁ bhaktaṁ na kadāpīty agāt tathā

Kṛṣṇa thought, “If necessary, I can give up everything, even my beloved Lakṣmī, however I am unable to abandon the bhakta-rice that has come within my grasp or the bhakta-devotee, who has come under my shelter.”33

Here again we have the example of a commentator’s dialogue elaborating upon k ṛṣṇ a-l ī l ā in a way that the original text of Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam does not.

And that is it!

y purpose over these last four sections was to give solid reasoning for the constant use of dialogue throughout my commentary to Vil ā pa-kusum ā ñjali . By doing so, I believe that I have expressed the spiritual principles underlying Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī ’s verses, while remaining faithful to our spiritual lineage. I have tried to achieve this in an interesting and educational way, while also rising to the challenge of the day, in which devotees have such easy access to so many rasika books outside of Śrīla Prabhupāda’s line. This literary device was employed by many ācāryas in and out of our line, and di ers little in methodology from the more familiar narrative of a philosophical explanation. In conclusion I will revisit the inevitable objection that comes up to my reasoning, which is that I do not fall into the category of the aforementioned scriptures or ācāryas.

Thus the fifth question, “While there may be precedent, do you have the eligibility of your predecessors?”

The subtle implication of this question is that because I am not as elevated as our ā c ā ryas , which is true, then I do not have the qualification to write, which is false.

Over and over again, we see that our ā c ā ryas never make a connection between their literary style and their liberated status.

This leads the honest person to conclude that dialogue is not for an exclusive class of commentators, but a standard literary genre accessible to all pure devotees.

Śrīla Prabhupāda certainly encouraged all his followers to write. He did not imply that one literary device [narrative] was acceptable and another [dialogue] was not.

Indeed, in the vikr īḍ itam verse, and in its commentaries by ācāryas, the qualification for both hearing, anuśṛṇuyāt, or describing, varṇayet, is pure faith in the spiritual nature of the subject matter. It is by those two activities that the heart gains absolute purity. Taking these points into consideration, we thus conclude on answering the fifth question.

While I am the first to agree that I am not in the league of the previous ācāryas, that does not mean that I am disqualified from this genre of composition.

Yes, I am qualified.

By following our ever-liberated ā c ā ryas , by remaining faithful to the original purpose of Dāsa Gosvāmī ’s work, and by Śrīla Prabhupāda’s order to write, I am qualified to put to pen my realisation on Śrī Vilāpa-kusumāñjali. And that realisation may be in the form of dialogue. This, too, is the opinion of Rūpa Gosvāmī:

mamāsmin sandarbhe yad api kavitā nātilalitā

mudaṁ dhāsyanty asyāṁ tad api hari-gandhād budha-gaṇāḥ apaḥ śālagrāmāplavana-garimodgāra-sarasāḥ sudhīḥ ko vā kaupīr api namita-mūrdhā na pibati

Although the poetry of my play is not very beautiful, still the wise will take delight in it, for it bears the scent of Lord Hari. After all, what learned man will not bow his head and respectfully drink well-water that has washed a śālagrāma-śīlā?34

Caitanya Mah ā prabhu’s words to Īś vara Pur ī on the same topic were similarly approving:

Smiling, Īś vara Pur ī said, “You are a great pa ṇḍ ita . I have written a book about Lord K ṛṣṇ a’s pastimes.

Please tell me all the mistakes in it. That would make me very, very happy.”

The Lord replied, “Only a sinner sees faults in a devotee’s words describing Lord Kṛṣṇa. A devotee does not write poetry whimsically, according to his own personal opinion. Therefore his poetry, presenting the conclusions of scripture, is always pleasing to Lord Kṛṣṇa.

mūrkho vadati viṣṇāya

dhīro vadati viṣṇave

ubhayos tu samaṁ puṇyaṁ

bhāva-grāhī janārdanaḥ

“‘An uneducated person may say ‘ vi ṣṇā ya ,’ and a learned person may say ‘ vi ṣṇ ave. ’ But noble-hearted Lord K ṛṣṇ a, who is only interested in the love of His devotees, accepts both these prayers equally.’

“One who sees faults in a devotee’s words is himself at fault. Simply by describing the Lord, a devotee pleases Lord K ṛṣṇ a. Who is so daring that he will find fault with your descriptions of spiritual love?”

As he heard the Lord’s reply, Īś vara Pur ī felt that his entire body was being splashed with nectar. Smiling, Īś vara Pur ī again said, “You will not find any faults. But there must be faults. Please describe them.”35

Kṛṣṇadāsa Kavirāja Gosvāmī expressed a similar view:

What does it matter that I cannot glorify all the Lord’s pastimes? By glorifying the Lord’s pastimes as far as one is able, a person becomes very fortunate. A person who glorifies the Lord’s pastimes as far as he is able is never to be mocked or derided. No one has the power to describe all the pastimes of the Supreme Lord.

Even if my book is full of faults, the wise, who become intoxicated by hearing songs about the Lord’s lotus feet, will still accept it. I have not a moment’s worry that they will not like it.36

I would be naive to think that the reasoning in the preceding twenty-six pages satisfies every one of my readers, what to speak of my critics. To these Vaiṣṇavas I o er the following two approaches to the dialogues in my commentary.

One: It is a recording of Ś ivar ā ma Swami’s meditations on Vil ā pa-kusum ā ñjali. It is my bhajana. The logic and precedents of this Preface substantiate that bhajana. However, if devotees have a problem with part or all of that reasoning, they can simply approach this book as my personal meditations on Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī ’s work.

Two: Devotees can consider that the conversations could have been written as “Were Rādhā to say...” and “Then Dāsa Gosvāmī would respond...”, or “Then Rati-mañjarī would respond…” and so on. However, to avoid the redundancy this repetition would cause, we dropped that approach. It is, however, implicit, and ultimately that is how the dialogues are meant to be understood.

conclude this Preface by briefly explaining the secondary literary devices employed in this commentary. When referring to Rādhā and Kṛṣṇa, Caitanya Mahāprabhu, and K ṛṣṇ a’s incarnations and their ś aktis, like rāyaṇa and Lakṣmī-devī, I have chosen to make subject pronouns and possessive pronouns in the lower case, rather than the bbt standard of upper case.

In earlier books I had used both standards: lower case for better visual e ect, and upper case for fidelity to the bbt. According to his editors, Śrīla Prabhupāda accepted both, but preferred lower case.37 My choice of lower case in Vilāpa-kusumāñjali was to blend in better with the informal setting and sweet exchanges characteristic of the book, and especially of the dialogues.

Moreover, L ā l Publishing has its own Style Guide, based

primarily on the Oxford English Style Guide (as we adhere to British grammar standards) and the Chicago Manual of Style, both of which are recognised worldwide as ultimate authorities on grammar and style. Both reject the use of upper-case pronouns for referring to the Lord in any form.

I trust that readers recognise that regardless of upper- or lower-case pronouns, Rādhā and Kṛṣṇa are equally supreme divinities, nonpareil.

The second device is the “for meaning” translation of both the verses of Vilāpa-kusumāñjali and the verses I quote in the commentaries. This was Śrīla Prabhupāda’s standard practice, since he was more concerned with reader comprehension than with fidelity to verbatim translation.

The rendering of Dāsa Gosvāmī ’s verses is based on translations by Kuśakratha Dāsa, Advaita Dāsa, and Lāl Publishing’s Sanskrit editors, Gabhīra Dāsa and Mañjarī Devī Dāsī. For the most part these translations agree, and where there is a variance in word or phrase meanings, the overall renditions are similar, if not identical. When it came to verses quoted in the commentaries, I took more liberty to not only facilitate understanding, but to beautify the language of the verse where translation facilitated it. Experience has it that from a literary point of view, the English translations of Sanskrit are often decades old, when editors were less qualified and practised than they are now; consequently those translations require quite a bit of editing and rewriting to blend in with my own style.

In addition to editing and beautifying verses from non- bbt sources, I have also taken the liberty of editing some bbt quotations. Śrīla Prabhupāda instructed his editors to correct grammatical flaws in his renditions and smoothen out the naturally bumpy text that emerges when translation is via dictation. Thus, in addition to changing pronoun upper-cases to lower, I have also made some simple changes without interfering with Śrīla Prabhupāda’s message. For example, in a verse from Caitanya-caritāmṛta, the bbt translation of kuñja is “bushes,” which I have changed to “groves.”38

Another example is the Padma Pur āṇ a verse beginning with n ā ma cint ā ma ṇ i ḥ k ṛṣṇ a ḥ . The bbt translation is in seven sentences, which sounds like literary staccato, and so I tried to make it smoother by recasting it in five sentences.

Like the examples above, edits of bbt quotations are minor, and yet they serve the cause of clarity, smooth reading, and consistency with my style.

As for referencing, I chose quite a sparse standard in Vil ā pakusumāñjali, endnoting only the verses that I quoted exactly and fully. That means I did not reference those sources which I paraphrased extensively, or combined fully or in part with other verses to form a di erent narrative. And I generally did not reference pastimes or anecdotes.

In terms of naming books in the endnotes, we adhere again to the guidance of the two previously mentioned style-guide authorities. Their practice is one of abbreviation: once a book is named in full in the endnote, it is thereafter referred to in its abbreviated form. For example, the first endnote reference of Ś r ī madBh ā gavatam is written in full, but subsequent endnotes will read as SB. This we have applied only to books well-known and easily-identified by devotees, ie: SB, Cc, Bg. Other less-familiar books retain their full name, ie: Govinda-līlāmṛta, Padyāvalī, and so on.

In Nava-vraja-mahimā I credited much more extensively; however, I found that process cluttered the endnotes and distracted the reader from important sources. Since our system is to repeat what we have heard, ultimately everything in this book—līlā, rasa, and tattva—could be referenced. Clearly that is impractical. Therefore, I took a sparing approach to citing authority. * * * *

will now offer readers an outline of the entire book, all five volumes. From the table below, one can see the eleven parts of this commentary, the first three of which are dedicated to Volume One, along with this Preface, the Introduction, and a biography of Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī. The volumes may or may not have Appendices; those only manifest upon writing.

The eleven Parts represent the common threads running through the verses included in them, and their names represent the general subject matter of those verses. Readers will note that the sequence of the Parts, and hence the Verses, is not chronological. This is in no way due to any fault on the part of the author, but rather an indication of his elevated spiritual station, in which he records actual pastimes as they manifest to him.

Volume One

Mangalācaraṇa

Preface

Introduction

Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī ’s Biography

Part One 01 – 06 Mangalācaraṇa

Part Two 07 – 12 Appeals in Separation

Part Three 13 – 17 Mañjarī-niṣṭhā

Volume Two

Part Four 18 – 44 Morning Dressing

Volume Three

Part Five 45 – 57 Afternoon Pastimes

Part Six 58 – 67 Cooking in Nandagrāma

Volume Four

Part Seven 68 – 81 Noontime Pastimes

Part Eight 82 – 93 Occasional Pastimes

Volume Five

Part Nine 94 – 96 Ultimate Surrender

Part Ten 97 – 100 Prayers to Rādhā’s Associates

Part Eleven 101 – 104 Concluding Prayers

Epilogue

The one hundred and four verses of Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī are individually named in the table of contents. The naming of both Verses and Parts is entirely mine, and to the best of my knowledge the author made no such demarcation or designation.

This current Volume One spans Parts One to Three—Verses One to Seventeen. It creates the foundation and sets the scene for the following volumes, and informs the reader what it means to enter into the realm of spontaneous devotion and conjugal love. The target of this book is the highest spiritual attainment available to any living entity. For most people, even the concept of mañjarī-bhāva is inconceivable, what to speak of its attainment. I hope that Volume One will inspire the readers to follow Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī ’s teachings and footsteps, and continue to read the subsequent volumes, which I hope and pray Śrīmatī Rādhārāṇī will allow me to complete.

hile not a literary style, I will comment on the length of this book, which is not the length it started out to be. The Nava-vraja-mahimā version of Vilāpa-kusumāñjali was two hundred and fifty three pages, and as things stand with Volume One, this version seems like it will be at least ten times longer. So it will be five volumes.

I accept that this is what Dāsa Gosvāmī and his worshipable deities want of me. The commentaries are my meditation, my bhajana. More than any other book I have written, Vilāpa-kusumāñjali embraces me and draws me into its fold. The result is that I am recording a personal meditation, which is often like an independent agent carrying me through the skies of transcendental pastimes.

The original plan was one volume, an elaboration on the earlier version. But my Kṛṣṇa consciousness, writing style, and the book itself, have all changed. Before, Vilāpa-kusumāñjali was a lengthy appendix; now it is my e ort to say whatever I have to say in the time I have left in this world. I anticipate that completion will take another three years after this first volume. Who knows what the future will bring? If the Lord gives me more time and inspiration, then I will write a commentary on rāsa-pañca-adhyāya, the five chapters in Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam describing Kṛṣṇa’s rāsa-dance pastimes.

I am greatly inspired to write Vil ā pa-kusum ā ñjali, and deeply indebted for the privilege of being able to do so. Although I could not do it without the entire production team at L ā l Publishing,

I do owe special thanks and gratitude to my long-time editor, Braja Sevakī Devī Dāsī, who is not only the chief editor of this book, but also a full-time consultant for style, content, and mood. This book is as much a meditation for her as it is for me.

And I hope that Vilāpa-kusumāñjali will prove to be a suitable meditation for my readers, especially for readers mature in the ways of bhakti-yoga, especially rāgānuga-bhakti. Although I write mainly for self-purification, I write also for the many devotees who encourage me to do so, who relish my work, and who find it conducive to their spiritual development.

The many pages of this book a ord extensive opportunity for Vaiṣṇavas to discuss the glories and pastimes of the divine couple, and the ways and means to serve them as a mañjarī. By reminding each other of what they have read and realised, devotees become absorbed in thoughts of the divine couple, and their spiritual attachment increases in leaps and bounds. As R ā dh ā - Ś y ā ma become increasingly pleased by their devotees’ e orts in bhakti-yoga, they free devotees of every last trace of impurity, and, at some point, infuse devotees with divine blessings. Raised to the transcendental platform, Vaiṣṇavas enter the realm of love, and begin to relish the ecstasies of bhāva-bhakti and the real taste of spontaneous devotion. When absorbed in n ā ma-sa ṅ k ī rtana meditations, devotees see themselves in their spiritual forms, following beside their mañjarī-guru. May my readers bless me with the same perfection.

smarantaḥ smārayantaś ca mitho ’ghaugha-haraṁ harim bhaktyā sañjātayā bhaktyā bibhraty utpulakāṁ tanum