Śrī Vilāpa-kusumāñjali

of Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī

With the Patrāṅkitā Commentary of Śivarāma Swami

Volume Four

Books by Śivarāma Swami

The “Kṛṣṇa in Vṛndāvana” Series: Śuddha-bhakti-cintāmaṇi – The Touchstone of Pure Devotional Service Veṇu-gītā – The Song of the Flute Na Pāraye ’Ham – I Am Unable to Repay You Kṛṣṇa-saṅgati – Meetings with Kṛṣṇa Śrī Dāmodara-jananī – Lord Dāmodara’s Mother Saṅkalpa-kaumudī – A Moonbeam on Determination Śrī Vilāpa-kusumāñjali of Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī, Patrāṅkitā Commentary

• Volume One: Appeals in Separation and Mañjarī-niṣṭhā (Verses 1–17)

• Volume Two: Morning Dressing I (Verses 18–32)

• Volume Three: Morning Dressing II (Verses 33–44)

• Volume Four: Afternoon and Evening Pastimes (Verses 45–57)

Tava Kathāmṛta – Nectarean Talks About Kṛṣṇa

The “Nava-vraja-mahimā” Set:

• Volume One: The Truth of the Dhāma – Mathurā, Nandagrāma, and Their Surroundings

• Volume Two: The Sacred Places of Kāmyavana, Yāvaṭā, and Varṣāṇā with Their Surroundings

• Volume Three: The Glories of Govardhana – Pastimes and Parikrama

• Volume Four: The Glories of Rādhā-kuṇḍa and a Commentary on Vilāpa-kusumāñjali

• Volume Five: The Areas of Ādi-badrī, Vṛndāvana Town, and Other Holy Places

• Volume Six: The Holy Places Along the Yamunā

• Volume Seven: The Glories of the Gāyatrī-mantra

• Volume Eight: The Glories of the Mahā-mantra

• Volume Nine: The Maps of New Vraja-dhāma

The “Awakening” Series:

The Awakening of Spontaneous Devotional Service

The Further Awakening of Spontaneous Devotional Service

The Śrutis Awaken to Spontaneous Devotion

Other works:

The Bhaktivedanta Purports – Perfect Explanations of the Bhagavad-gītā

The Śikṣā-guru – Implementing Tradition Within iskcon

Śikṣā Outside iskcon

Sādhavo Hṛdayaṁ Mahyam – Saints Are My Heart

My Daily Prayers

Varṇāśrama Compendium – The Varṇas, Volume One

Gauḍīya-stotra-ratna – The Gemlike Prayers of Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇavas

Śrī Vilāpa-kusumāñjali – A Rendering

Collected Writings (based on lectures, vlogs, and podcasts):

Chant (E-book)

Chant More

Life in a Faltering World

Truth in the Midst of Turmoil

Śrī Vilāpa-kusumāñjali of Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī with Śivarāma Swami’s Patrāṅkitā Commentary “Words Inscribed Upon a Petal”

VOLUME FOUR

KṚṢṆA IN VṚNDĀVANA 9

Based on the writings of A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupāda and the previous ācāryas

Kṛṣṇa in Vṛndāvana Volume Nine

Śrī Vilāpa-kusumāñjali of Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī With the Patrāṅkitā Commentary of Śivarāma Swami Volume Four

© 2025 Śivarāma Swami

© 2025 Magyarországi Krisna-tudatú Hívők Közössége, SRS Books, Hungary

Managing Director: Manorāma Dāsa

Editor: Braja Sevakī Devī Dāsī

Substantive Editors: Mañjarī Devī Dāsī

Yaśodā-dulāla Dāsa

Copy Proofers: Haladhara Dāsa

Final Production Editor & Indexer:

Mahābhāva Dāsa

Revatī Devī Dāsī

Sanskrit Editors: Éva Lupták

Gabhīra Dāsa

Harivaṁśa Dāsa

Mañjarī Devī Dāsī

Bibliographer & Reference Editor: Éva Lupták

Artists:

Taralākṣī Devī Dāsī

Gāndharvikā Devī Dāsī

Smṛti-pālikā Devī Dāsī

Viśvambhara Dāsa

Layout Designer: Sundara-rūpa Dāsa

Quotes from the books, lectures, letters, and conversations by His Divine Grace A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupāda © The Bhaktivedanta Book Trust International 1966-1977. Used with permission.

ISBN 978-615-6379-38-2

Printed in Hungary

This publication is not for sale, but is made available worldwide to interested parties who wish to donate to MKTHK, SRS Books.

Readers interested in the subject matter of this book are invited to contact us or visit the following websites: books@sivaramaswami.com

www.srsbooks.com www.sivaramaswami.media

Dedication

This book is dedicated to Śrīla Prabhupāda, who taught that chanting hare kṛṣṇa means to request Śrīmatī Rādhārāṇī to accept us as her maidservants and thus engage us in her service.

In the beginning of the Hare Kṛṣṇa mahā-mantra we first address the internal energy of Kṛṣṇa, Hare. Thus we say, “O Rādhārāṇī! O Hare! O energy of the Lord!” When we address someone in this way, they usually say, “Yes, what do you want?” The answer is, “Please engage me in your service.” This should be our prayer.

–– His Divine Grace A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupāda, Teachings of Lord Kapila 32, Purport.

Verse

VERSE 45

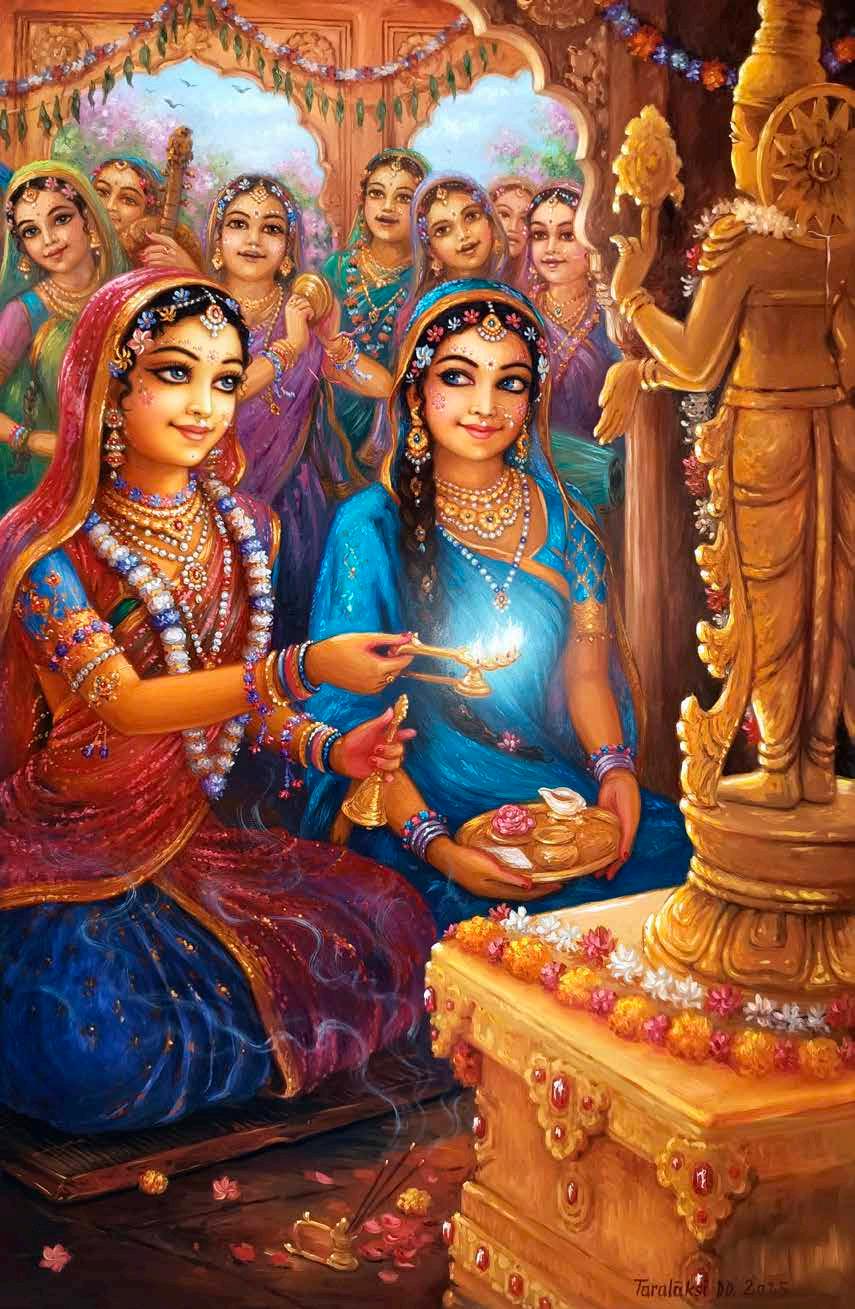

Worshipping the Sun God

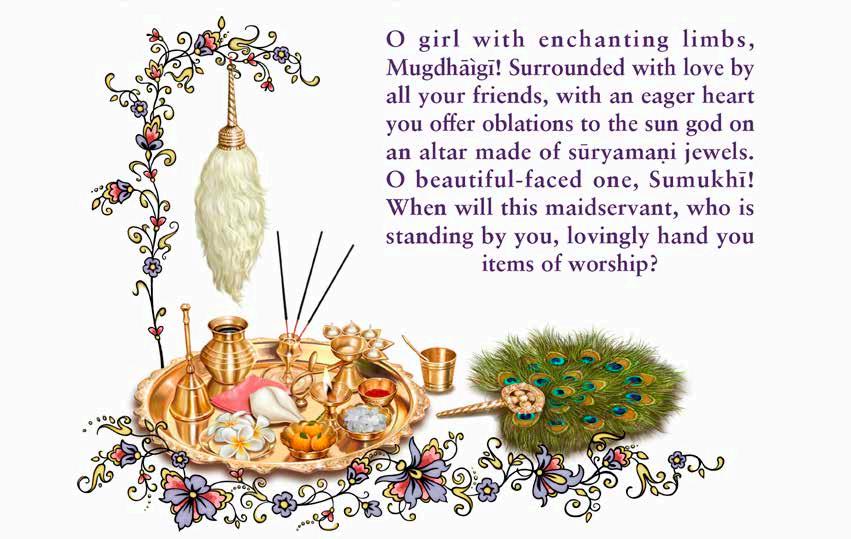

sūryāya sūrya-maṇi-nirmita-vedi-madhye mugdhāṅgi bhāvata ihāli-kulair vṛtāyāḥ arghyaṁ samarpayitum utka-dhiyas tavārāt sajjāni kiṁ sumukhi dāsyati dāsikeyam

sūryāya—to the sun god; sūrya-maṇi-nirmita—made of sun stones; vedi-madhye— on an altar; mugdhāṅgi— O girl with enchanting limbs; bhāvata—with love; iha—here; āli-kulaiḥ—by your friends; vṛtāyāḥ— surrounded; arghyam— oblations; samarpayitum— to offer; utka-dhiyaḥ—eager in your heart; tava—your; ārāt—vicinity; sajjāni—paraphernalia; kim—when; sumukhi—O beautiful faced girl; dāsyati—will give; dāsikā—maidservant; iyam—this.

O girl with enchanting limbs, Mugdhāṅgī! Surrounded with love by all your friends, with an eager heart you offer oblations to the sun god on an altar made of sūryamaṇi jewels. O beautiful-faced one, Sumukhī! When will this maidservant, who is standing by you, lovingly hand you items of worship?

Commentary

One widow says,

EFORE RĀDHĀ LEAVES the palace with her retinue of sakhīs and mañjarīs, she must first offer her respects to her husband’s family. This morning, her mother-in-law Jaṭilā is accompanied by some village friends who, while making a fuss over beautiful Rādhā and her equally beautiful companions, unleash veiled slurs about the Nandagrāma destination of the girls.

“Rādhā, dear! Will that journey to Nandagrāma not be too taxing for you?”

Another neighbour chimes in,

“I have heard that a dacoit haunts the back roads.”

A slightly hunchbacked lady adds,

“And he is very fond of exploiting newlywed girls.”

Although Jaṭilā says nothing, she basks in the carping of her friends.

Intolerant of even the slightest criticism of Rādhā, Lalitā has to exercise restraint to resist the temptation of giving the old witches a tongue-lashing. With Rādhā’s hand held firmly in her own, she casually replies to the old crones,

“Honourable ladies! We are under the orders of Queen Yaśodā and are therefore protected by her authority and purity.”

Viśākhā continues,

“Long ago, Yaśodā-mā decreed that Śrī Rādhā cook for her son,

and so, as much as we would like to, we cannot remain with you to make cow-dung patties.”

When Rādhā was just a child, the great sage Durvāsā gave her the blessing that anyone who tasted her cooking would have a long life, be freed of disease, and enjoy protection from demons. Although Rādhā’s cooking needs no blessings from anyone, this arrangement was made by Kṛṣṇa’s yoga-māyā to cover Rādhā’s divine status and to facilitate her earthly pastimes.

Rādhā and her friends therefore have good reason to comply with Queen Yaśodā’s extraordinary request that Rādhā cook daily for a man other than her husband. This allows Kṛṣṇa to taste the conjugal ambrosia of her cooking, and occasionally meet her in his own home.

Now it is time for Tuṅgavidyā to speak.

“It is well known that the saint Durvāsā has blessed Rādhā that whoever tastes her cooking will be free of disease, old age, and death.”

Lalitā concludes their retorts to the old hags, saying,

“But to ensure that our friend is safe, we girls are all accompanying her, carrying vetras to thrash any dacoit who dares accost us.”1

One of the old women chortles and points a crooked finger at Rati.

“And I suppose this little wisp of a girl is your commander?”

All the women, young and old, look at Rati, who wants to melt away in shame. But Lalitā boldly steps forward in Rati’s defence.

“I am the commander. I am well-versed in all kinds of śāstric knowledge, including vetra-vidyā, the art of stick fighting. ”

Looking lovingly at Rati, Lalitā adds,

“And Tulasī carries my vetras. She is my indispensable assistant.”

The old women look quite impressed by Lalitā’s argument. Seeing that she is on a winning streak, Lalitā concludes,

“Now, with your blessings and without delay, we shall pray for auspiciousness to the sun god.”

Feeling a rare surge of affection for her daughter-in-law, Jaṭilā fondly strokes Rādhārāṇī’s arm, and croaks,

“Go, my dear! Go and please Queen Yaśodā and bring back many gifts of necklaces and rings in return. This will greatly please my son Abhimanyu.”

At the mention of Abhimanyu’s name, Rādhā’s sister-in-law Kuṭilā speaks up.

“Where is my beloved brother, the sun of our dynasty, the protector of cows, and the munificent husband of Rādhā?”

Hearing such praise of the miserable Abhimanyu, Rādhā’s friends turn here and there in search of a place to hide their giggles.

Jaṭilā answers her daughter,

“He left early for the market to purchase more cows, which will increase our wealth and prestige.”

Jaṭilā’s hooked nose touches her mouth as she speaks, and her deeply wrinkled face contorts in humorous ways. Always dressed in black, her vision faltering, and her tongue the home of gossip and fault-finding, Jaṭilā is a figure of ridicule, well known by village children as “the witch of Yāvaṭā.”

As for Kuṭilā, she is a hopeless spinster, always the main figure of the latest plot to catch Rādhā with Kṛṣṇa, and best described in Kṛṣṇa’s own sarcastic words:

My dear Kuṭilā! Your breasts are like string beans—dry and long; your nose is more beautiful than that of a frog’s, and your eyes are just like those of a rabid dog. Since your lips defy the flaming cinders of fire and your abdomen the shapeliness of a drum, I think you are the most beautiful gopī in Vṛndāvana, and the only one who spurns the spirited songs of my flute!2

At this time, Kundalatā arrives to escort Śrīmatī Rādhārāṇī to Nandagrāma. As the two girls embrace, Jaṭilā addresses Yaśodā’s envoy.

“Kundalatā-putrī! You are from the noble family of Upananda, and so I place my daughter Rādhā in your care. She is chastity personified, so you must ensure that the son of Nanda comes no closer to her than is required to eat what she cooks.”

Undertaking a hundred promises, Kundalatā repeats the daily ritual of reassuring the old woman again and again, and then, taking Rādhā by the hand, they step out of the house and into the courtyard, leaving the palace grounds and proceeding along the path that leads to the temple of the sun god.

As soon as they are out of earshot, the girls begin joking among themselves. Citrā-devī gently pokes Lalitā and says,

“O Lalitā! Why have you been hiding secrets from us?”

With an air of detachment, Lalitā retorts,

“Dear Citrā! What are you babbling about?”

“We did not know that you were studying vetra-vidyā. Why is it that you are hiding such perfections from us?”

Before Lalitā can reply, intelligent Tuṅgavidyā speaks in her sakhī’s defence,

“As far as I know, it is the sage Vātsyāyana who in his Kāma-sūtra advises all women to perfect the art of vetra-vidyā.”

Now it is Kundalatā who takes up the baton of poking fun at Lalitā.

“Tell us, my dear! Did you begin honing your skill in vetra-vidyā before or after you learned some of the Kāma-sūtra’s secret arts of lovemaking?”

Lalitā is incensed, but Citrā cannot resist adding,

“And is that why you enlisted Rati as your personal assistant? We know that while she appears to be shy, she is very expert in guiding gopīs along the esoteric paths of intimacy.”

Lalitā flushes red with anger, and Rati with shame. Considering this discussion too trivial, Lalitā simply raises high her head and says,

“I advise my loose-lipped friends to be sober in the presence of the sun god, whose temple we have almost reached.”

* * * *

he setting of Rādhā’s pastimes has now dramatically changed for Rati, as has the interaction between her and the princess. Moments earlier, the two had been alone in Rādhā’s dressing chamber, chatting about Kṛṣṇa. Now, they are in the midst of a boisterous congregation of gopīs, and heading first to the nearby Sūrya temple for pūjā before arriving at Nandagrāma. Among the many senior sakhīs, Rati is merely a junior attendant following the lively group down the narrow lanes of their village.

She thinks,

“How fortunate is this insignificant gopī to be dressing Śrī Rādhā. I touched her soft limbs, saw her divine form, listened to her honeyed voice, and inhaled her intoxicating fragrance.”

Rati stumbles, her mind more in the dressing room than on the uneven stones paving her way.

“How intimate were our talks, how free our laughter, how loving the atmosphere.”

The mañjarī can see the back of Śrīmatī Rādhārāṇī’s veiled head, and yet she feels separation from her. By comparison to the intimacy they had shared earlier, she thinks that the princess might as well be on the other side of Vraja.

It feels like the worst misery!

Rati’s heart pines for that same confidential exchange, yet her intelligence reminds her that such opportunities are rare. After all, other gopīs should also have that good fortune. Still, her mind cannot help but hanker. Her constitution is defined by divine greed, and no amount of logic can pacify her. She can only be satisfied by direct service to Rādhā and by nothing else, nor by service to anyone else.

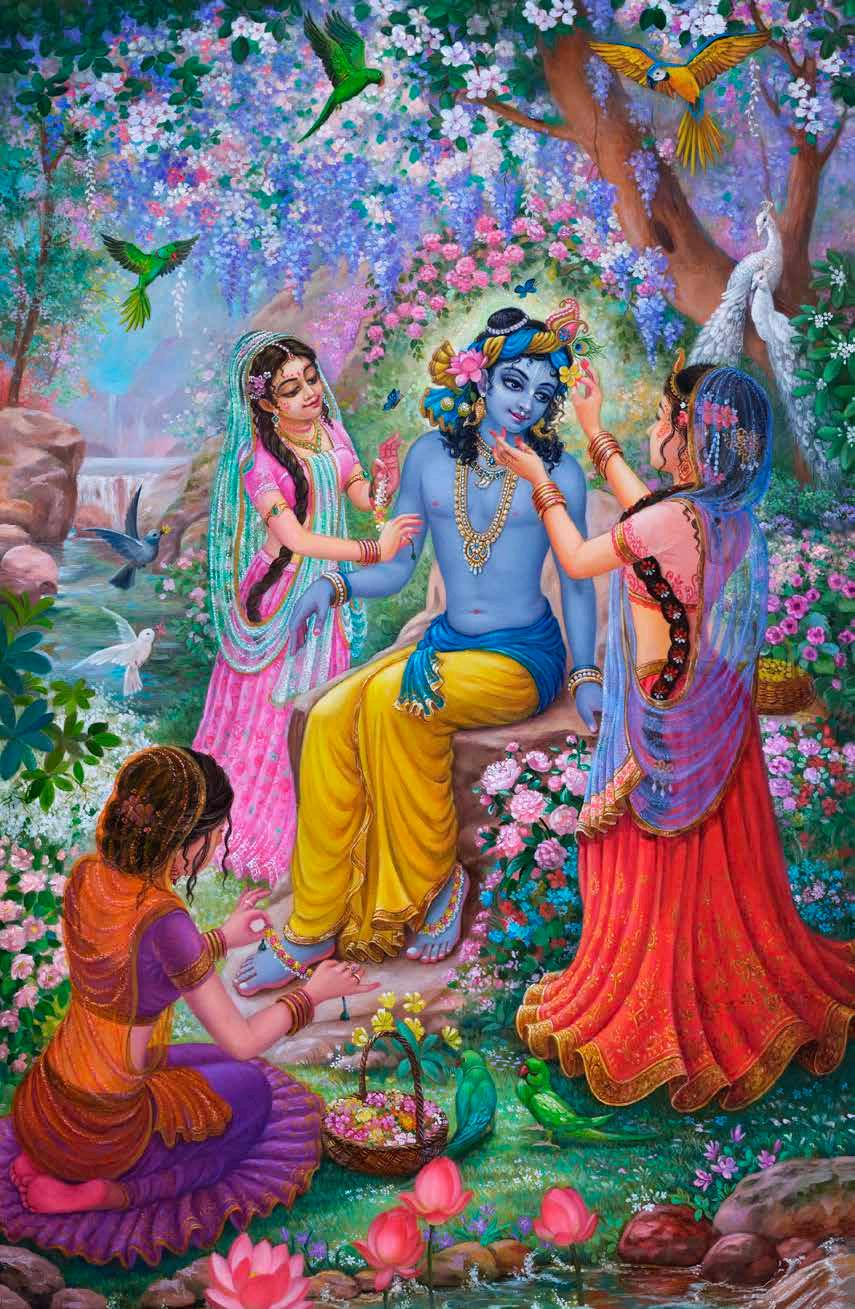

The girls reach the temple of Sūrya. Their chatting subsides, and they offer respects as they enter the darśana-maṇḍapa.

“Oṁ sūryāya namaḥ.”

“Oṁ mitrāya namaḥ.”

“Oṁ hiraṇyagarbhāya namaḥ.”

Rati can see Rādhā seated before the deity and performing ācamana. Then the princess pauses and turns, carefully scanning her followers. She is looking for someone. Softly she calls out,

“Tulasī! Where is Tulasī?”

Rati’s heart soars. Heads turn, looking for Tulasī, and the hand of a nearby gopī tugs at her wrist.

“Fortunate girl! Rādhā is calling for you.”

There is no envy in the gopī’s voice, nor are any of the other girls envious of Rati, because in Vṛndāvana such mundane defects do not exist. Śukadeva Gosvāmī explains:

yatra naisarga-durvairāḥ sahāsan nṛ-mṛgādayaḥ mitrāṇīvājitāvāsadruta-ruṭ-tarṣakādikam

Vṛndāvana is the transcendental abode of the Lord, where there is no hunger, anger, or thirst. Though

naturally inimical, both human beings and fierce animals live there together in transcendental friendship.3

In Vṛndāvana, the material qualities of ignorance are absent in everyone and everything, as Kṛṣṇa’s physical presence dispels such undesirable qualities and dissolves all disturbances. The residents of that land therefore experience an all-pervading sweetness, and live together as friends.

As Rati stands, the others turn towards her like sunflowers to the sun. Again she hears that angelic voice,

“Tulasī! Bring the items of pūjā and sit here.”

Rādhā pats the floor beside her with her left hand, and then again touches water for purification. Rati walks carefully past seated sakhīs like Viśākhā, Maṇi-mañjarī, and Kundalatā. In her daze, she does not even notice someone placing the pūjā tray in her hand. Her head bowed in shyness, she reaches the door of the deity room.

Rādhā gestures with her head and says,

“Sit here and keep the tray in your lap.”

Rati does as she is instructed, then performs ācamana for purification. The temple is quite small. The darśana-maṇḍapa barely seats the gopīs, and the deity room fits only a few worshippers, who at present are Rati and Śrīmatī Rādhārāṇī.

Rati looks at the golden deity sitting on the ruby-red, sunstone altar, and then she turns to Rādhā, seated on a simple kuśa mat. In the fresh morning air, she can smell the aroma of Rādhā’s divine body. Rati thinks to herself,

“Who is the deity, and who is the worshipper?”

She feels a nudge from Rādhā, and she quickly focuses her thoughts, handing her mistress three lighted sticks of incense. As Rādhā starts to wave the aromatic incense, the gopīs sing an ārati song while gently playing hand cymbals and beating gongs. The sounds are beautiful and melodic, and as the saṅkīrtana goes on,

Rati looks at the golden deity sitting on the ruby-red, sunstone altar, and then she looks to Rādhā. She thinks to herself, “Who is the deity, and who is the worshipper?”

Rati offers Rādhā one item of worship after the other—a ghee lamp, water, pressed silk cloth, flowers, a small cāmara, and a peacock fan.

Throughout the ārati, Rati only looks towards Rādhā, watching her facial expressions and gentle arm movements. Although the princess is seated, it appears as if she is performing a rhythmic dance, rather than worshipping a deity.

For a few moments Rati is lost in thought, trying to grasp just what it is that makes Rādhā’s confined, seated movements appear like the celebration of a festival. Then she understands.

“It is the exquisite beauty and grace of Rādhā’s limbs—her head, neck, arms, and hands; the elegance and flow of her movements; the poise with which she sits; and the unsurpassed beauty and nobility of her facial features. This is why I call her ‘girl with enchanting limbs,’ Mugdhāṅgī, and ‘beautiful-faced girl,’ Sumukhī.”

During these moments, which in Rati’s mind graciously extend themselves manyfold, the mañjarī’s attention is fully absorbed in the lake of Rādhā’s bodily beauty, whose waters flow with countless ripples of ecstasy, and whose movements are fanned by the ever-restless winds of love.

Śrīmatī Rādhārāṇī’s face is like a hundred-petalled golden lotus. Some petals express different facets of her beauty such as charm, grace, mystery, and reserve, while other petals represent the different parts of her face—eyes, mouth, nose, and ears.

Her eyes are two dark-blue petals of mystery, whose exceptional hue is a result of their infatuation with the bluish-black bumblebee that constantly seeks the honey-nectar of her lips—two other exceptional petals which have turned red due to the bhramara constantly alighting upon them.

Rādhā’s nose is a petal that the flurries of love have fully folded to capture the bodily fragrance of the Kṛṣṇa-bee, while her ears are two petals alert with eagerness to hear the strains of her visitor’s humming voice and vibrating flute.

As the golden lotus of Rādhā’s face sways left to right, the majestic lotus leaf of her neck concurrently sways right to left, always eager to capture the remnants of Kṛṣṇa’s attributes as they drip from her eyes, nose, lips, and ears.

Yet the leaf should not be mistaken to be just a beggar of nectar.

It is also a maestra of transcendental sounds. The midrib—the vein that runs along the middle of the leaf—is her voice, and it is the source of an extraordinary vibration that shames the songs of Kṛṣṇa’s flute and halts his proud humming.

When the prasāda of Rādhā’s face mixes with the nectar of her voice, a special dew forms on the edge of the leaf and falls, drop by drop, into the waters of her beauty, from whose surface the leaf and lotus rise.

And so the waters of Rādhā’s beauty are sweetened and nourished by Kṛṣṇa’s qualities, which in turn vitalise her facial features. Thus Śrī Rādhā’s face becomes increasingly attractive to the Kṛṣṇa-bee, who by tasting her sweetness becomes increasingly enlivened and more and more handsome.

While Rādhā’s facial beauty and expressions are without peer, Rati’s attention cannot help but be drawn to the hypnotic movements of Rādhā’s arms, like lotus stems swaying in the winds of love.

And just as the dancing stems of a lotus rise above a lake’s surface, so Rādhā’s gracious, slender arms undulate in a way that escapes the power of words to describe, or the mind to fathom. Perhaps they are more like the spellbinding motions of a dancing cobra, although the snake-dance is vertical, while in Rādhā’s ārati offering, her arms are horizontal.

In whatever way their movements appear, the effect of Rādhā’s arms—be it visual, tactile, or olfactory—is like that of the ropes of Cupid: they completely restrain their victim and make him helpless in the fetters of their charms.

Swaying with the movement of Rādhā’s lotus-stem arms are the two delicate lotuses of her gold and pinkish hands, which are the source of unlimited benediction for everyone, including Kṛṣṇa.

The silk-smooth backs of Rādhā’s hands, like her golden wrists, proclaim both the divine bliss and the realised knowledge of which she is the personification. And the pinkish-red of her palms is both her unparalleled compassion for conditioned souls who have forgotten Kṛṣṇa, as well as the generosity with which she offers herself to her beloved and to those who love him.

With great difficulty, Rati draws her meditation away from Rādhā’s undulating arms, and in so doing, inevitably catches sight of her svāminī’s entire form—so graceful, noble, and charming.

The creator’s greatest achievement was fashioning Śrīmatī Rādhārāṇī’s beautiful form, the lure with which Cupid captures Kṛṣṇa’s mind and senses, transforming the supreme controller into a puppet of the love-puppeteer.

Contemplating her queen, Rati thinks,

“Śrī Rādhā displays aristocracy by more than a noble birth and hereditary title. Her bodily poise and grace speak of a divine nobility that the loftiest echelons of social hierarchy cannot imitate. Serenity, dignity, and self-control are visible in the way she sits, in the way she stands … in fact, in every move she makes.

“Rādhā’s personal qualities are the ornamental symbols of her sovereignty. Her confidence in her total control over Kṛṣṇa is her crown, thinking of the welfare of others is her sceptre, stylish dressing is her mantle, and her noble posture is her royal slippers. My Devī is Vṛndāvaneśvarī in every sense of the word.”

Rati would have sunk even deeper into the quicksand of her Rādhā meditations, but a nudge from her right makes her aware of where she is and what her duties are. It is Rūpa-mañjarī, always attentive to Śrīmatī Rādhārāṇī’s needs, and keen to see that her disciple is fulfilling her service to their goddess.

Rati turns to Rūpa, who motions with her head to Śrīmatī Rādhārāṇī, now rising to her feet to address her friends.

“Sakhīs! Come! We must not be late in reaching Nandagrāma.”

Caught off guard, Rati quickly collects the used ārati paraphernalia and hands it to her assistant. She and the gopīs rise in a flurry of movement, with their skirts rustling and their lively chatter resuming. There is much excitement about the adventures with Kṛṣṇa that the morning may bring.

Like a regal queen gliding through the assembly of her courtiers, Rādhā walks past her friends, with Rati following close behind. It is a good distance to Nandagrāma, and the girls all fall in line while trying to be as close to Rādhārāṇī as possible.

* * * *

he first volume of this Patrāṅkitā commentary on Vilāpakusumāñjali consists of seventeen verses—the first six are the invocation, and the following eleven are Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī’s hankering for perfection.

Volumes Two and Three cover Verses Eighteen to Forty-four, which describe Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī’s account of Śrīmatī Rādhārāṇī’s early-morning bathing and dressing. Although Rādhā’s bath, massage, and dressing take only twenty-four minutes, or one daṇḍa, the description of this pastime is more detailed than any other in Dāsa Gosvāmī’s book, encompassing one quarter of the entirety.

This Verse Forty-five follows in sequence from the previous volume, which concluded Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī’s meditations on preparing Śrī Rādhā for her morning sojourn to Nandagrāma. From Verses Forty-six through Fifty-seven, the Gosvāmī jumps ahead without any warning to describe pastimes in the late afternoon and early evening. Similarly without explanation, Verses Fifty-eight through Sixty-seven follow chronologically from here, Verse Forty-five. In the verses following Sixty-seven to the conclusion of Vilāpa-kusumāñjali, the sequence of events is again broken. Readers generally expect the content of a book to flow in a chronological order. When it does not, and there is a change in the course of events, it is expected that the author will at least indicate the transition to either the past or the future.

However, after Verse Forty-five, Vilāpa-kusumāñjali presents the pastimes out of sequence, without any indication of the changes in the time frame.

The natural question is, “Why?”

The answer is that Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī lives in the realm of transcendence, where time does not flow in a linear sequence from past to future, but exists in the eternal present in the way described by the creator:

sa yatra kṣīrābdhiḥ sravati surabhībhyaś ca su-mahān nimeṣārdhākhyo vā vrajati na hi yatrāpi samayaḥ bhaje śvetadvīpaṁ tam aham iha golokam iti yaṁ vidantas te santaḥ kṣiti-virala-cārāḥ katipaye

I worship Goloka, pure and uncontaminated, where extensive oceans of milk flow from the cows, where not even a moment of time passes, and which only a few rare devotees wandering this Earth have realised.4

Moreover, Dāsa Gosvāmī describes his personal ecstasies as they inspire him, and those ecstasies are not obligated to align with the expectations or impositions of material time, or of his readers.

And as we shall see, the literary standards for transcendental compositions require neither chronological consistency nor an indication of imminent inconsistency.

An example of a practice similar to Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī’s is shown in Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam. In this mature fruit of the desire tree of Vedic literatures, nigama-kalpa-taror galitaṁ phalam, the great sage Śukadeva Gosvāmī is also seen to describe events out of sequence.5

For example, while recounting Kṛṣṇa’s Vṛndāvana pastimes, Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam concludes the Lord’s childhood līlā with the description of Brahmā’s bewilderment, and then inaugurates Kṛṣṇa’s boyhood with the pastime of killing Dhenukāsura. However, before going on to the next pastime—the killing of Pralamba—the sage’s ecstasy inspires him to narrate the chastisement of Kāliya, which is a return to Kṛṣṇa’s childhood.

The cited verse from Brahma-saṁhitā reveals that the spiritual realm, in which the samādhi of pure devotees is fixed, is characterised by the eternal present. This means all of Kṛṣṇa’s pastimes are concurrent. Therefore, Śukadeva Gosvāmī perceives the kāliya-līlā and pralamba-līlā simultaneously.

While ignorant souls will see his lack of chronological consistency as a fault, those who are learned will appreciate it as a perfection of Śukadeva’s consciousness. What we see as one līlā occurring in the past and another in the future, the sage sees as concurrent events.

Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī is blessed with the same transcendental vision. Suddenly attracted by Rādhā’s early evening pastimes, he diverts to describing them, but later returns to where he left off with the morning pastime.

Of further interest in this regard is that neither Dāsa Gosvāmī nor any editors of Vilāpa-kusumāñjali —if there were any— corrected the sequence of pastimes . The same may be said for Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam. We therefore conclude that the literary tradition is such that this apparent anomaly is not open to correction, but remains an excellence of these books, as it does of others.

Another feature of Verse Forty-five is that there are two possible alternatives in regard to the location and timing of the Sūrya-pūjā pastime. Both alternatives are detailed in the coming pages.

The first possibility is that Rādhā and her friends are worshipping a deity of Sūrya somewhere in or near Yāvaṭā. This would make the verse consistent with earlier pastimes that are taking place in Rādhā’s suites, and also with the gopīs and mañjarīs setting out from Rādhā’s home for Nandagrāma and stopping at a nearby Sūrya temple on the way.

The other alternative is that this verse refers to Rādhā’s afternoon devotions to the famous Sūrya-Nārāyaṇa deity at Sūryakuṇḍa, the worshipable Lord of the Vraja-vāsīs. After pastimes at Rādhā-kuṇḍa, Rādhā goes to Sūrya-kuṇḍa every Sunday, and on any other afternoon when circumstances permit.

Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī gives no indication of which alternative it may be, but both are possible.

Another question arises as to why the Vraja-vāsīs worship demigods when they live with the Supreme Person, and whether such worship also goes on in Goloka Vṛndāvana, Kṛṣṇa’s eternal home.

The worship of demigods takes place in both Bhauma Vṛndāvana and Goloka Vṛndāvana, because in both abodes the lives of the Vraja-vāsīs mirror those of the many conditioned souls who adore celestials. The Vraja-vāsīs remain oblivious to Kṛṣṇa’s divinity wherever they are, and simply consider him one of them, a cowherd.

Yet the Vraja-vāsīs’ form of worship differs from that of ordinary beings, whose worship is based on their material desires for results from demigods. The Vraja-vāsīs are pure devotees, and their prayers and offerings are for Kṛṣṇa’s well-being and protection. They have no selfish desires, and are filled only with overwhelming love for Kṛṣṇa.

Some of the residents of Vraja, like Nanda Mahārāja, worship incarnations of Kṛṣṇa, while others like Govardhana Malla— the husband of Candrāvalī-devī and a close friend of Abhimanyu— worship Durgā-devī. There is, however, a difference between the devas of Earth and those of Goloka.

While the demigods in the material world are mostly elevated conditioned souls empowered for universal management, those in the spiritual world are perfected souls who, like all of Kṛṣṇa’s

associates, eternally serve the Lord’s pastimes. But unlike the Vraja-vāsīs, who appear as humans, these devotees appear in the capacity of the Vraja-vāsīs’ worshipable deities, demigods.

* * * *

hether sequential or not, the verses of Vilāpa-kusumāñjali are the testament of an associate of the Lord, and they are also a stimulant for sādhakas’ attraction for the conjugal mellow. Ṭhākura Bhaktivinoda writes,

Practising devotees should render service in their purified minds according to the methods and moods illustrated in Vilāpa-kusumāñjali.6

In Ujjvala-nīlamaṇi, Rūpa Gosvāmī describes four types of stimulants for the conjugal mellow:

uddīpana-vibhāvā hares tadīya-priyāṇāṁ ca kathitā guṇa-nāma-carita-maṇḍana-sambandhinas taṭasthāś ca

The stimuli, uddīpanas, among the causes of love, vibhāvas, are said to be Kṛṣṇa’s and his dear lovers’ qualities, names, activities, and decorations, as well as related items and neutral elements like the wind or the full moon.7

It should be noted that the stimuli of love defined above relate to both Kṛṣṇa and to the gopīs, tadīya-priyāṇāṁ ca. Since Kṛṣṇa and the gopīs are both viṣaya and āśraya for each other, the qualities of one become the impetus of love for the other. In terms of relishing rasa, Viśvanātha Cakravartī Ṭhākura comments that sādhakas primarily taste the mood of the gopīs towards Kṛṣṇa, and secondarily Kṛṣṇa’s love towards the gopīs. 8

Since kṛṣṇa-prema includes love of his dear associates, sādhakas who aspire to be mañjarīs can, by loving Kṛṣṇa, also savour the mood that prāṇa-sakhīs such as Rati-mañjarī feel towards Rādhā. This mood of the mañjarīs may be relished by hearing of the things

that stimulate their love. The uddīpana-vibhāvā śloka establishes the beloved’s qualities, names, activities, and decorations as those stimuli.

Rūpa Gosvāmī elaborates on the things that constitute decoration:

caturdhā maṇḍanaṁ vāso-bhūṣā-mālyānulepanaiḥ

There are four kinds of decoration: garments, ornaments, garlands, and cosmetics.9

These four items are the subject of Volumes Two and Three. There, along with Rādhā’s names, her beautification is the dominant stimulant, whereas her pastimes and qualities take a secondary and occasional role. Now, from Volume Four to Volume Eight, Rādhā’s beautification as a stimulant is secondary, while her pastimes and qualities come to the fore.

As explained, whichever verse or volume is perused, the words of Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī and this commentary will act as a stimulus to increase the reader’s attraction to the perfection of mañjarī-bhāva. To advance in such devotion, one must have faith in the transcendental nature of the subject matter, must be attentive to it, and must be submissive to its message. Readers who possess these qualities will find their eagerness for the path of the mañjarīs irrevocably established within their heart. This is confirmed by the words of Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam:

sadyo hṛdy avarudhyate ’tra kṛtibhiḥ śuśrūṣubhis tat-kṣaṇāt

As soon as one attentively and submissively hears the message of Bhāgavatam, by this culture of knowledge the Supreme Lord is established within his heart.10

When qualified Vaiṣṇavas attentively hear the message of Vilāpakusumāñjali, it nourishes their attraction to serving Śrīmatī Rādhārāṇī in a way similar to how Rati-mañjarī serves her.

* * * *

rīmatī Rādhārāṇī generally leaves her home thrice daily. In the morning, she goes to Nandagrāma to cook Kṛṣṇa’s breakfast, returning home as he leaves to tend the cows. Towards noon, she goes to Rādhā-kuṇḍa on the pretext of worshipping the sun god, and then returns mid-afternoon. In the evening, she travels to the bank of the Yamunā near Vaṁśīvaṭa, and returns home just before dawn.

When Rādhā-Kṛṣṇa and the gopīs go about their pastimes during these three times of the day—indeed, as long as they reside in Vṛndāvana—they are always in their original transcendental forms. This is the case eternally in Goloka Vṛndāvana, and for as long as the divine couple are visible on Earth.

However, when Kṛṣṇa and Rādhā appear outside Vṛndāvana, it is never in these original forms but in their expansions, and those expansions only manifest a portion of the originals’ potencies. It is therefore said that Kṛṣṇa in Vṛndāvana is most perfect, while in Mathurā he is more perfect, and in Dvārakā he is merely perfect. Caitanya Mahāprabhu says,

kṛṣṇasya pūrṇatamatā vyaktābhūd gokulāntare pūrṇatā pūrṇataratā dvārakā-mathurādiṣu

The most complete qualities of Kṛṣṇa are manifested within Vṛndāvana; his more complete and his complete qualities are manifested in Mathurā and Dvārakā, respectively.11

Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura explains this variance in Kṛṣṇa’s display of his qualities:

He is glorified in three ways according to the degree to which his qualities are manifest: pūrṇa, complete; pūrṇatara, more complete; and pūrṇatama, most complete. His form in which all of his qualities such as beauty, sweetness, and opulence are manifest in the most complete way is called pūrṇatama, and this form

is manifest in Vṛndāvana. He appears in his most complete form of Bhagavān only there, because that is where his associates express the ultimate limit of prema. In all other places he manifests as either pūrṇa or pūrṇatara, according to the level to which prema is developed in his associates of that abode.12

In the Sanat-kumāra-saṁhitā, Lord Sadāśiva elaborates on the perfections of Kṛṣṇa’s different forms. He compares these to the phases of the moon—when full, it has sixteen phases, or kalās; when less full, fifteen kalās; and when even less full, fourteen kalās. Sadāśiva says to Nārada Muni,

vraja-rāja-suto vṛndā-vane pūrṇatamo vasan sampūrṇa-ṣoḍaśa-kalo vihāraṁ kurute sadā

Nanda’s son, the Prince of Vraja, who stays in Vṛndāvana forest and enjoys pastimes there eternally, and who is like a perfectly full moon, is the most-perfect form of the Supreme Personality of Godhead.

vāsudevaḥ pūrṇataro mathurāyāṁ vasan puri kalābhiḥ pañca-daśābhir yutaḥ krīḍati sarvadā

Vasudeva’s son, who stays in Mathurā city and enjoys pastimes there eternally, and who is like a moon one day before being perfectly full, is the more-perfect form of the Supreme Personality of Godhead.

dvārakādhipatir dvāra-vatyāṁ pūrṇas tv asau vasan caturdaśa-kalā-yukto viharaty eva sarvadā

The King of Dvārakā, who resides in Dvārakā and enjoys pastimes there eternally, and who is like a moon two days before being perfectly full, is the perfect form of the Supreme Personality of Godhead.13

Lord Sadāśiva goes on to explain,

vraje śrī-kṛṣṇacandrasya santi ṣoḍaśa-śaktayaḥ poṣikā madhurasyaiva tasyaitā vai sanātanāḥ

In Vraja, sixteen eternal potencies expand the sweetness of Lord Kṛṣṇacandra.

These eternal potencies are divided into two categories: the internal energy, antaraṅga-śakti, and the external energy, bahiraṅga-śakti.

The internal energies are: pastimes of sweetness, mādhurya-līlā; love, prema; form, svarūpa; maintenance, sthāpanī; attraction, ākarṣaṇī; union, saṁyoginī; separation, viyoginī; and bliss, hlādinī.

The external energies are: beauty, śrī; maintenance, bhū; pastime, līlā; control, yoga-māyā; conceivability, cintyā; inconceivability, acintyā; enchantment, mohinī; and expertise, kauśalī.

Compared to Vṛndāvana, Kṛṣṇa in Mathurā manifests these energies less fully, and as the King of Dvārakā even less so. Viśvanātha Cakravartī Ṭhākura explains this variance in detail:

Kṛṣṇa’s four residences, in their descending order of potency, are Vraja, Mathurā, Dvārakā, and Goloka.

Kṛṣṇa, Baladeva, and their family, along with Vraja, are pūrṇatama, most complete. In Mathurā, Kṛṣṇa and his residence are pūrṇatara, more complete. In Dvārakā, where he resides with Pradyumna, Anuriddha, and their dependants, Kṛṣṇa and his residence are pūrṇa. In Goloka, Kṛṣṇa and his residence are pūrṇa-kalpa, full of excellences. Because Kṛṣṇa’s pastimes in Goloka are on the same level as they are in Vṛndāvana, Kṛṣṇa in Goloka is pūrṇatara-sajātīya, similar in substance but not the same.

The element of mādhurya can be found in an increasing order respectively in Goloka, Dvārakā, and Mathurā, and fully in Vṛndāvana. The element of aiśvarya is concealed in proportion to the manifestation of mādhurya, and shines more as mādhurya decreases. This means that Goloka has more aiśvarya

and less mādhurya; Dvārakā has more mādhurya and less aiśvarya than Goloka; Mathurā has more mādhurya and less aiśvarya than Dvārakā; and Vṛndāvana displays mādhurya in its fullness.14

Sanat-kumāra-saṁhitā explains a similar variance of perfections manifested by Śrī Rādhā.

Of all the sixteen potencies of Kṛṣṇa, the hlādinī potency is known as the mahā-śakti, or the supreme, original, governing śakti, which finds its personification in Śrīmatī Rādhārāṇī. In this original form, Śrī Rādhā eternally relishes transcendental pastimes with the son of Nanda Mahārāja. Therefore Rādhā, like Kṛṣṇa, never leaves Vṛndāvana. The following well-known verse substantiates Kṛṣṇa’s eternal presence in his divine home:

kṛṣṇo ’nyo yadu-sambhūto yaḥ pūrṇaḥ so ’sty ataḥ paraḥ vṛndāvanaṁ parityajya sa kvacin naiva gacchati

The Kṛṣṇa known as Yadu-kumāra is Vāsudeva-Kṛṣṇa. He is different from the Kṛṣṇa who is the son of Nanda Mahārāja. Yadu-kumāra Kṛṣṇa manifests his pastimes in the cities of Mathurā and Dvārakā, but Kṛṣṇa the son of Nanda Mahārāja never at any time leaves Vṛndāvana.15

It is reasonable to conclude that the original Rādhā also never leaves Vṛndāvana, because she is described as Kṛṣṇa’s mahā-śakti and is therefore inseparable from him.

Spiritual authorities confirm that like Kṛṣṇa, Rādhā eternally resides in Vṛndāvana. In Sva-niyama-daśaka, Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī writes,

sadā rādhā-kṛṣṇocchalad-atula-khelā-sthala-yugaṁ vrajaṁ santyajyaitad yuga-virahito ’pi truṭim api punar dvārāvatyāṁ yadu-patim api prauḍha-vibhavaiḥ sphurantaṁ tad-vācāpi ca na hi calāmīkṣitum api

Even though I suffer in long separation from the divine couple, and even if the King of the Yadus comes to my door and with sweet words invites me to visit his capital of Dvārakā, still I will not leave incomparable Vraja-bhūmi, the place that gives one the taste of transcendental mellows, and where Rādhā-Kṛṣṇa eternally perform their unparalleled pastimes.16

From this verse it is clear that Rādhā-Kṛṣṇa eternally reside in Vṛndāvana, a conclusion shared by other devotee scholars such as Prabodhānanda Sarasvatī and Viśvanātha Cakravartī Ṭhākura.

Returning to the Sanat-kumāra-saṁhitā, we find Nārada asking a poignant question:

How can Rādhā feel separation from Kṛṣṇa when he leaves Vṛndāvana in his Vāsudeva form? It would appear to be a conflict of mellows for her to be attached to an opulent expansion of Vṛndāvana’s Kṛṣṇa.

In the same vein, in the next verse of the very same Sva-niyamadaśaka, the author indicates that if Rādhā becomes overwhelmed by separation, she may go to Dvārakā to be with her Lord. Dāsa Gosvāmī writes,

gatonmādai rādhā sphurati hariṇā śliṣṭa-hṛdayā

sphuṭaṁ dvārāvatyām iti yadi śṛṇomi śruti-taṭe tadāhaṁ tatraivoddhata-mati patāmi vraja-purāt samuḍḍīya svāntādhika-gati-khagendrād api javāt

But were I to hear that Śrī Rādhā, overcome with the madness of divine love, has gone to Dvārakā to be with Śrī Kṛṣṇa, then at that very moment I will leave Vṛndāvana and, with an excited heart, fly to Dvārakā faster than the auspicious king of birds, Garuḍa.17

The author clearly states that Śrī Rādhā not only feels separation from Dvārakādīśa, but that she would also leave Vṛndāvana. This appears to contradict his earlier assertion that Rādhā eternally enjoys with Kṛṣṇa in Vraja, an assertion that requires clarification to resolve the apparent conflict of mellows implied.

In the gatonmādai rādhā sphurati verse, the circumstance of Rādhā’s visit to Dvārakā is hypothetical, for Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī qualifies his vow with the words yadi śṛṇomi, “if I hear.”

And yet the circumstances of Rādhā going to Dvārakā need not be entirely theoretical. The ācārya could be addressing the real possibility of Śrī Rādhā appearing outside of Vṛndāvana. After all, Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam describes the gopīs travelling to Kurukṣetra to see Kṛṣṇa, and Lalita-mādhava describes how, by committing suicide, Rādhā is eventually transferred to Dvārakā. Therefore, the appearance of Rādhā outside of Vṛndāvana has a precedent.

Resolution to this quandary is provided by śāstra, which explains that neither of Rādhā’s appearances in Dvārakā or Kurukṣetra are the original Vṛndāvaneśvarī, but are instead her expansions.

As previously established, the daughter of Kīrtidā and Vṛṣabhānu, like the son of Yaśodā and Nanda, never leaves Vṛndāvana. Gopāla Guru and Dhyānacandra Gosvāmīs cite the Sanat-kumārasaṁhitā as a reference that speaks of Rādhā in Dvārakā by the name of Vāmā-Rādhā, and Rādhā in Kurukṣetra by the name of Kāmā-Rādhā:

śaktiḥ saṁyoginī kāmā vāmā śaktir viyoginī hlādinī kīrtidā-putrī caivaṁ rādhā-trayaṁ vraje

In Vraja, Śrī Rādhā exists in three forms: as Kāmā, who is the personification of union, saṁyoginī-śakti; Vāmā, the personification of separation, viyoginī-śakti; and Kīrtidā-putrī, the personification of the original pleasure potency, hlādinī-śakti. 18

When Kṛṣṇa is seen to leave Vṛndāvana for Mathurā, the original fountainhead Rādhā knows that her beloved has simply hidden himself and that it is Vāsudeva-Kṛṣṇa who has left. However, her two expansions, Kāmā and Vāmā, are not aware of Kṛṣṇa’s eternal presence in Vṛndāvana. For them, he has factually left for broader horizons.

Rūpa Gosvāmī’s Lalita-mādhava recounts how Vāmā-Rādhā was so overcome with separation from Kṛṣṇa that she committed suicide by entering the waters of the Yamunā River. Yamunā-devī, daughter of the sun god, then transported Vāmā to the sun globe. Rādhā left there after some time to appear in Dvārakā as Satyabhāmā.

Later, Kāmā-Rādhā also experienced intense separation, and so she, along with other gopīs and Vraja-vāsīs, went to meet Kṛṣṇa and Balarāma when the Yadus travelled to Kurukṣetra to celebrate a major solar eclipse. This meeting is described in ŚrīmadBhāgavatam, and the gopīs’ desire to bring Kṛṣṇa from Kurukṣetra to Vṛndāvana is immortalised by the Ratha-yātrā festival.

eturning to the two verses of Dāsa Gosvāmī’s vows, a contradiction between them raises an interesting topic: it appears that the ācārya is eternally in Vṛndāvana, and yet would also travel to Dvārakā.

This lack of congruence between the two verses is resolved in light of how the original Rādhā and her eternal associates expand.

In the verse beginning gatonmādai rādhā sphurati, Raghunātha Dāsa states that if Vāmā-Rādhā appeared in Dvārakā, then he would leave Vṛndāvana in the blink of an eye.

But would he?

To leave Vṛndāvana would mean to leave the daughter of Kīrtidā and his service to her as Rati-mañjarī. How could he possibly do that? As Rati-mañjarī, Raghunātha would never leave Kīrtidā’s daughter, a truth confirmed in the verse beginning with sadā rādhā-kṛṣṇocchalat. And yet in the next verse, gatonmādai rādhā sphurati, he vows that he would.

The resolution to these two opposing situations is that, like Rādhā, Rati-mañjarī would manifest another form, one that is fully compatible with Vāmā-Rādhā. The result would be that in her original form, Rati-mañjarī remains in Vṛndāvana, and in another form, she follows Vāmā-Rādhā to Dvārakā.

As an eternally liberated associate of Rādhā-Kṛṣṇa, it is possible for Rati-mañjarī to accept multiple forms. This is evidenced in Sanātana Gosvāmī’s explanation of how Kṛṣṇa’s Goloka associates

serve their Lord and Mistress by expanding themselves in Dvārakā, Vaikuṇṭha, Svarga, and on Earth:

eṣām evāvatārās te nityā vaikuṇṭha-pārṣadāḥ prapañcāntar-gatās teṣāṁ pratirūpāḥ surā yathā

yathā ca teṣāṁ devānām avatārā dharā-tale krīḍāṁ cikīrṣato viṣṇor bhavanti prītaye muhuḥ

Just as the demigods who have entered the material creation are counterparts of the Lord’s Vaikuṇṭha associates, those eternal associates from Vaikuṇṭha are incarnations of the Goloka devotees. Yet like the demigods themselves, those very devotees appear on Earth now and again for the pleasure of Lord Viṣṇu when he wants to enjoy various pastimes.19

And just as the incarnations of Kṛṣṇa, the source of all incarnations, are non-different from him, the incarnations of the Goloka-vāsīs are non-different from them.

The Goloka-vāsīs are born sometimes as partial expansions, and sometimes as their full selves. Like Kṛṣṇa, they vary their appearance according to the time, place, and need.

In the verses cited, as well as others from Bṛhad-bhāgavatāmṛta and the commentaries therein, Sanātana Gosvāmī clearly elucidates how an eternal associate of Śrīmatī Rādhārāṇī can be in both Vṛndāvana and in Dvārakā.

Raghunātha Dāsa vows that if Vāmā-Rādhā is overcome by separation and leaves Vṛndāvana, then he would accompany her. While such a vow is possible for an eternal associate of Rādhā, it is but a meditation for a sādhaka. However, in one’s meditation it is possible to be both in Vṛndāvana and Dvārakā as Rati-mañjarī’s protected assistant. In this way, practising devotees may share Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī’s vow and be spiritually reinforced.

A concluding aspect of this topic is how Caitanya Mahāprabhu absorbed himself in the mood of Rādhā and her expansions. This is helpful for sādhakas who are keen to learn from Caitanya Mahāprabhu how to feel separation from Kṛṣṇa.

When Mahāprabhu danced before the cart of Lord Jagannātha, he expressed the feelings of Rādhā and the Vraja-vāsīs when they were in Kurukṣetra. It is now apparent that when the Lord speaks the following as Rādhā, he was absorbed in the mood of Kāmā-Rādhā, the saṁyoginī-śakti:

prāṇa-nātha, śuna mora satya nivedana vraja—āmāra sadana, tāhāṅ tomāra saṅgama, nā pāile nā rahe jīvana

My dear Lord, kindly hear my true submission. My home is Vṛndāvana, and I wish your association there, but if I do not get it, then it will be very difficult for me to keep my life.20

The evidence from the Sanat-kumāra-saṁhitā also sheds further light on the two verses of Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī.

In the verse that begins with sadā rādhā-kṛṣṇocchalat, he clearly states that Rādhā and Kṛṣṇa are eternally in Vṛndāvana. The daughter of Kīrtidā would not be the Rādhā who, in the verse beginning gatonmādai rādhā sphurati, has journeyed to Dvārakā. That gatonmādai rādhā was maddened by feelings of separation, which indicates that she is Vāmā-Rādhā.

Hence Caitanya Mahāprabhu’s moods of intense separation from Kṛṣṇa in the Gambhīrā are either as Vāmā-Rādhā, or as Kīrtidā-sutā.

When Mahāprabhu feels separation for Kṛṣṇa—who has left Vṛndāvana for Mathurā, and thereafter for Dvārakā—he adopts the identity of Vāmā-Rādhā or Kāmā-Rādhā, as expressed in this well-known verse spoken by Mādhavendra Purī:

ayi dīna-dayārdra nātha he mathurā-nātha kadāvalokyase

hṛdayaṁ tvad-aloka-kātaraṁ dayita bhrāmyati kiṁ karomy aham

O my Lord! O most merciful master! O master of Mathurā! When shall I see you again? Because of my not seeing you, my agitated heart has become unsteady. O most beloved one, what shall I do now?21

According to Kṛṣṇadāsa Kavirāja Gosvāmī, when Mahāprabhu was in Purī he always tasted Rādhā’s separation from Kṛṣṇa after the latter had left Vraja for Mathurā.22 This would indicate that during the Lord’s descent, he was mostly in the mood of Kīrtidā-sutā’s expansions.

However, when Lord Caitanya felt separation because Kṛṣṇa was at a distance in Vṛndāvana, or when he was participating in vraja-līlā, then he was in the mood of Vṛndāvaneśvarī.

Separation from Kṛṣṇa while he is still in Vṛndāvana is of four kinds: separation before having ever met, pūrva-rāga; when Kṛṣṇa has gone to tend cows, pravāsa; when Rādhā’s anger has banished Kṛṣṇa to a nearby grove, māna; and imagined separation in Kṛṣṇa’s presence, prema-vaicittya.

Some examples of how Caitanya Mahāprabhu relished these feelings include the time when he was praising the unlimited sweetness of Kṛṣṇa with Sanātana Gosvāmī, or when he was extolling the glories of Kṛṣṇa’s food remnants. Both incidents are described in Caitanya-caritāmṛta.

These are some of the different moods of separation that Caitanya Mahāprabhu tasted as Rādhā and her expansions during his various pastimes.

This and the preceding section have described how Śrīmatī Rādhārāṇī expands into two similar forms, and how those expansions satisfy their feelings of separation from Kṛṣṇa when he leaves Vṛndā vana. Like Kṛṣṇa, the original and most perfect form of Rādhā never leaves Vṛndāvana. She resides there eternally, fulfilled by pastimes of unparalleled sweetness with the original and most perfect form of the Supreme Lord. And the divine couple’s eternal associates also remain in Vraja in their original forms while

expanding themselves to serve the expanded forms of Rādhā and Kṛṣṇa.

Finally, Nārada’s question in the Sanat-kumāra-saṁhitā is answered. When Vāsudeva-Kṛṣṇa exhibits pastimes in Mathurā or Dvārakā, Vṛndāvana-Kṛṣṇa enters into his aprakaṭa-līlā along with the original Rādhā. Therefore, the daughter of King Vṛṣabhānu does not exhibit separation from Mathurānātha or from Dvārakādīśa, for she is eternally associating with Vrajanātha-Kṛṣṇa. The original form of Rādhā feels separation from the original form of Kṛṣṇa when he is away from her during his eternal pastimes within Vṛndāvana. Her forms of Kāmā, saṁyoginī-śakti, and Vāmā, viyoginī-śakti, feel separation from the forms Kṛṣṇa takes when he is outside of Vṛndāvana. This is how Rādhā’s separation from Kṛṣṇa away from Vṛndāvana should be understood.

aghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī addresses Śrī Rādhā as Sumukhī, meaning “girl with a beautiful face.” Hearing this name, Rādhā jokes with her maidservant,

“Are you mistaking me for one of Lalitā’s sakhīs?”

There are eight priya-sakhīs serving under Lalitā-devī’s guidance, and Sumukhī is one of them. Rati immediately catches on to her mistress’s humour.

“No, Devī! And I certainly did not mistake you for Madhumaṅgala’s mother!”

Both girls laugh heartily, and Rādhā continues, “Who on earth would want to be that braggart’s mother!”

Still on the path to Nandagrāma, they quickly check that Madhumaṅgala is not nearby, careful that the brāhmaṇa not overhear their chatter. Rati says,

“At least there is one Sumukhī who seems to relish the role, and loves even fat-bellied braggarts.”

Again the girls laugh, and again they look about. Rati continues, “But Goddess! The Sumukhī of whom I speak regularly worships the sun with a prayer that begs the king of planets to slow its morning ascent.”

“Why would someone want to slow the rising of the sun?”

The mañjarī replies,

“Because Sumukhī wants a few extra minutes to rest in her lover’s arms.”

Rādhā shakes her right forefinger at Rati, “Tulasī! There you go again. Everything you say always concludes in amour.”

In her own defence, Rati says,

“But Sumukhī does not love the ultimate conclusion of all wonderful things.”

“If you are speaking of the Apsarā of Alakāpurī, who is always absorbed in such matters, then perhaps this is so! But there is no Aṣṭāvakra Muni here in Vraja.”

Rādhārāṇī is referring to a wanton Apsarā courtesan of heaven named Sumukhī, who once danced at Kuvera’s court in honour of the famed Aṣṭāvakra Muni.

Rati is of two minds. Should she change the subject, or pursue the argument implying that she is not the only one who always thinks of love? Opting for the middle ground, she quotes the words of Rādhā’s close friend,

“Well, I know that Viśākhā speaks of a Sumukhī who is always absorbed in her lover.”

Hearing her best friend’s name, Rādhā is somewhat defensive.

“What does Viśākhā say?”

“Once, when she was encouraging Sumukhī to take shelter of her lover, I heard Viśākhā-devī say,

kastūryāḥ sat-tilakam alike yas tavoroja-yugme citraṁ binduḥ sumukhi cibuke netra-yugme ’ñjana-śrīḥ

śrutyor indīvara-viracitaḥ kuntale cāvataṁsaḥ so ’yaṁ kāntaḥ sphurati sakhi te bhāgya-rāśir vrajāmum

“O Sumukhī! Beautiful-faced Rādhā! The person who now greets your eyes is the same person as the musk tilaka that you apply to your forehead, the pictures you have us paint on your breasts, the black dot you cherish on your chin, the kajjala you smear on your eyes, the ornament of blue lotuses on your ears, and the bluish garland in your hair. O my friend! He who you place

all over your body is that same dark lover of yours who languishes in all good qualities. Do not waste time. Go to him now.”23

Considering that Rati had recently applied all the substances spoken of by Viśākhā, and that while doing so she had spoken of them as an impetus to remember Kṛṣṇa’s love, it is hard for Rādhā to continue the challenge to her maidservant. As an alternative, she too chooses the middle ground, speaking of herself in the third person,

“Yes, there is a beautiful-faced person called Sumukhī who, even on a night filled with rumbling clouds, gives up sleep and leaves her home to search after some tamāla -coloured boy who she is obsessed with.”

As Rādhā speaks, she remembers the night when darkness had swallowed the world and Viśākhā woke her to meet Hari. But now the rising force of separation from him actually deludes her into believing that she is a person different from Sumukhī-Rādhā, and so she laments on behalf of another.

“Poor Sumukhī! She went to meet Kṛṣṇa on the advice of friends, yet he never arrived at her grove. Now her mind is vacant in disappointment, and although she places betel nuts in her mouth, she is so overcome that she forgets to chew them. And so, as the night passes, she stands there absent-minded, her mouth full of unchewed betel.”

With love-filled eyes, Rādhā sees Kṛṣṇa finally arrive before the Sumukhī-heroine, who turns her back on him and refuses to acknowledge his apologies and excuses.

Speaking to the vision evoked by her ecstasy, Rādhā says,

“O angry lady! The name Sumukhī indicates that indifference, vimukhī, is not proper conduct for you.

“O beautiful woman! Your lover has come without being called, and the chalice of his heart is overflowing with great affection. Give up your anger! It is not proper to reject a hero who has come of his own accord.”

Deeply absorbed in her vision of lovers’ pastimes, Rādhā turns to Rati and, lightly rubbing her eyes as if to see better, she asks whether Rati has heard of these lovers meeting after a long night’s vigil.

From Rādhā’s ecstatic condition, Rati understands that her queen is lost in her own world, and that their word-sparring has come to an end. She must now assist her mistress’s ecstasies, although there remains a dichotomy between them. Rādhā speaks of another gopī, while Rati speaks of Rādhā. The mañjarī says,

“O Devī! The prefix ‘su’ in the name Sumukhī indicates that she and Kṛṣṇa are suitable for mutual affection. Because Sumukhī’s face is like the moon, she inevitably brings light to the darkness of their separation. How could it be otherwise!”

Rādhā is delighted to hear that the girl Sumukhī finally secures Kṛṣṇa’s company. She says,

“That gallant lover must have spoken sweet words to pacify his beloved. Please let me hear what he said.”

Rati complies,

“O Goddess! When Kṛṣṇa saw that his beloved was eager to hear words of admiration, he recited verses that won Sumukhī’s heart. This is one such verse:

rādhe tvan-mukha-sammukham eva vikāsy akṣi me sumukhi ānandayati hi kumudaṁ kumuda-suhṛt kevalaṁ candraḥ

“O beautiful-faced Rādhā! O Sumukhī! Gazing into your face makes my eyes blossom with happiness, and so the entire world is thrilled, whereas the moon— friend of the kumuda lotus—brings happiness only to the kumudas.”24

Rādhā is pleased. Although Rati has quoted her name, ecstatic love blinds Rādhā to its implication, and so she continues to speak of another.

“That is so lovely. Hearing his words, she must have opened her heart and freely showered her love upon him.”

Rati must bring Rādhā to full external consciousness and to the realisation, if not the admission, that she is the Sumukhī of her divine reverie. Responding to her mistress, Rati says,

“You are right. Rūpa-mañjarī was watching from a distance as the two lovers sat in the courtyard of the grove where they had earlier displayed expertise in pastimes of love.”

“And then?”

“Kṛṣṇa touched her breast and she in turn tilted her neck, resting it upon his shoulder. Gazing upon him from the corner of her eye, she frowned, exhibiting a slight pique.”

“Oh? Tell me, there must have been more.”

Rati answers her eager goddess.

“Yes, Sumukhī! The hairs of her body standing on end, beautiful-faced Rādhā glanced sideways, her heart melting, then wiped the tears of joy from her face with his yellow cloth, displaying a complete lack of reverence.”

In the tug of war between Rati, who is eager to bring her princess to full consciousness, and prema, which still blinds Rādhā to the person of whom they speak, the latter remains the stronger.

Rādhā claps her hands in appreciation of the mellows of transcendental love. She sighs,

“Although the heroine could have offered Kṛṣṇa respect, she did not. Instead, her many signs of intimacy were a display of pure love, praṇaya.”

Rati does not reply, reasoning that silence is her best recourse. Rādhā looks into her eyes, waiting for a response. When there is none, she murmurs in little more than a whisper, “Tulasī.”

Rati replies,

“O girl with enchanting limbs, Mugdhāṅgī! Surrounded with love by all your friends, with an eager heart you offer oblations to the sun god on an altar made of sūryamaṇi jewels. O beautiful-faced one, Sumukhī! When will this maidservant, who is standing by you, lovingly hand you items of worship?”

The divine potency, prema, loosens its grasp on Rādhā, and she gradually comes to external consciousness. Yes, she is Sumukhī. She has been the subject of their conversation all along. After all, Rati only ever speaks of one gopī.

Now her mañjarī has placed a request before her, and after a moment’s reflection she answers in softly spoken words.

“So you would like to help with the worship of the sun god.”

Rati replies with a solitary, “Yes!”

“Then so it shall be! I called you for this morning’s worship, and I will do the same when we greet the lord at Sūrya-kuṇḍa. Until then you may stay by my side.”

Rati-mañjarī has no desire other than staying by Rādhā’s side, night and day. Having received Rādhā’s order, she can hardly contain her bliss. But she must now control herself, because during the remainder of the morning until midday, and throughout the course of the afternoon, she will be called upon to serve the divine couple in many ways. Yet Rati has a special fondness for Sūrya-pūjā, because it is laden with so much humour, double-talk, and disguises.

he afternoon Sūrya -pūjā takes place following RādhāKṛṣṇa’s dice game in the all-green kuñja of Sudevī. Just as the divine couple are in the heat of their dice throws, a parrot suddenly arrives bearing the terrible news that Jaṭilā is quickly approaching Sūrya-kuṇḍa.

Just the name “Jaṭilā” is enough to instil fear of God in Kṛṣṇa and the gopīs. Concerned that the old woman could be passing by Rādhā-kuṇḍa, everyone giggles in anxiety and runs off to Kuñjara, a special grove to the north. While Kundalatā accompanies Rādhā to the sun temple, Kṛṣṇa takes help from Vṛndā’s sylvan goddesses to disguise himself in a way suited to the pastime, and so the gopa son of Nanda now becomes the brāhmaṇa Viśvaśarmā.

When out-of-breath Rādhārāṇī arrives at Sūrya-kuṇḍa, Jaṭilā is already there to greet her with a mouthful of rebukes.

“There you are! I have been waiting for you girls for ages.”

Rādhā and her friends offer praṇāmas, and in chorus say,

“Respected lady! We have been at the Ariṣṭa-grāma lakes.”

Jaṭilā turns to Rādhā, asking,

“What were you doing at your lake?”

Hardly able to speak, Rādhā murmurs,

“Mother! We took bath to purify ourselves for worship.”

“But why are you so late? I have never met a girl who takes so long to bathe.”

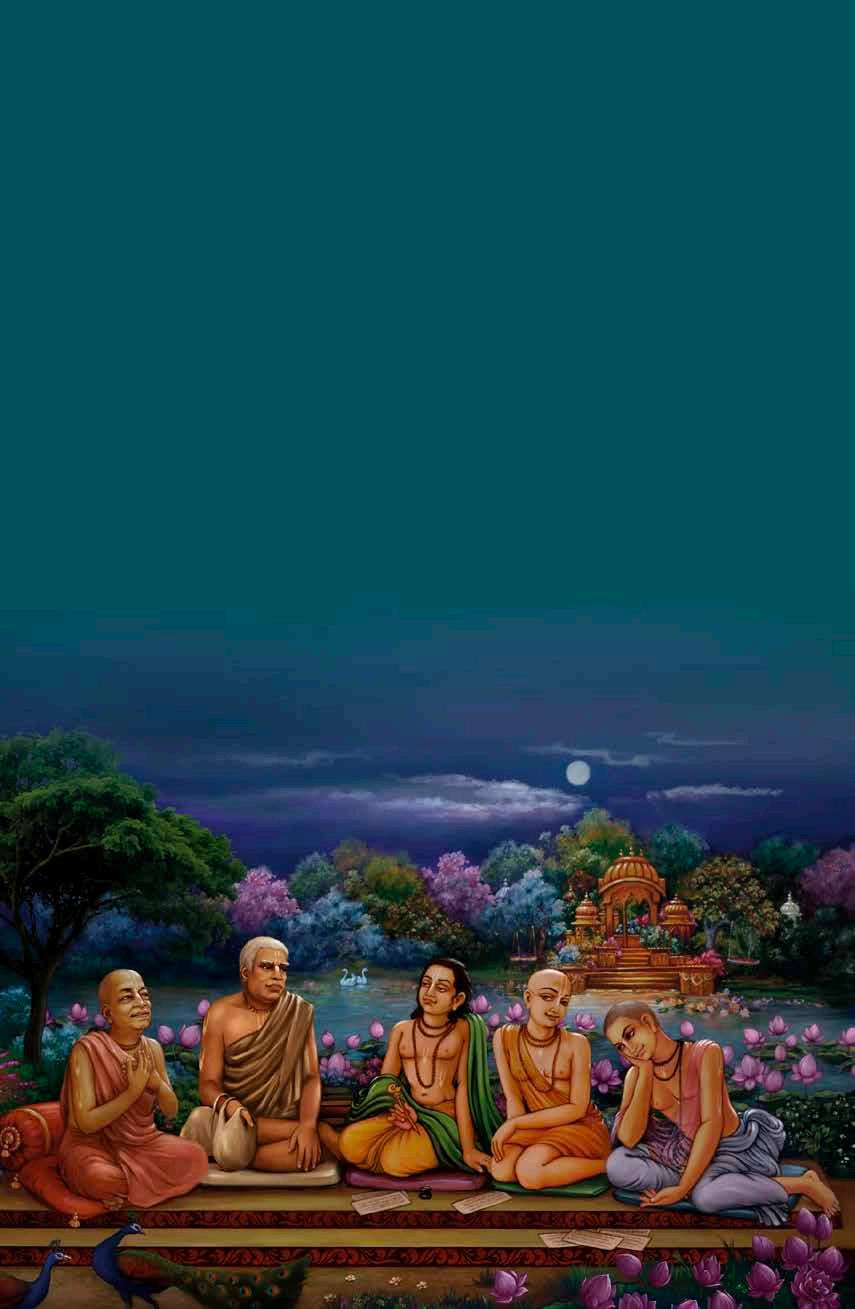

ay Śrīla Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī consider me his dependent. He is the principal rūpānuga - vaiṣṇava, the eternal friend and follower of Śrīla Rūpa Gosvāmī. He personally witnessed the most intimate pastimes of Lord Caitanya under the care and guidance of Śrīla Svarūpa Dāmodara Gosvāmī. Lord Caitanya gave him Govardhana as his residence and the service of Śrīmatī Rādhikā as his only engagement. His sādhana is the standard for all Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇavas. As he lay weeping on the banks of Rādhā-kuṇḍa, his heart breaking in separation from Śrī Rādhikā, his lamentations ( vilāpa ) poured forth in the form of a handful of flowers (kusumāñjali). This Śrī Vilāpa-kusumāñjali is the central jewel on the necklace of prayers (stavāvalī), which always adorn him. I shall keep this jewel as my most valuable treasure and await the time when I may reap its riches.

Tamāla Kṛṣṇa Goswami Vyāsa-pūjā homage, 1992

Based on the commentaries of Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī, Jīva Gosvāmī, Viśvanātha Cakravartī Ṭhākura, Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura, and Śrīla A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupāda.