EXPLORING LOCHABER’S ICE CAVES Neil Adams It is a common misconception that most snow and ice is to be found on the tops of mountains. Even during the Ice Age, this was never really the case. Although more snow might fall on the tops, due to a combination of wind and gravity most of this snowfall ends up just below the peaks, plateaus and ridges. It is in the high level corries and gullies that most of the wind-blown and avalanched snow ends up. Here it gets trapped in shaded hollows, nooks and crannies and, as more snow builds up over the course of a Scottish winter, this snow gets compacted into ice. Under its own weight, the upper layers of snow squeeze out air from the lower

24

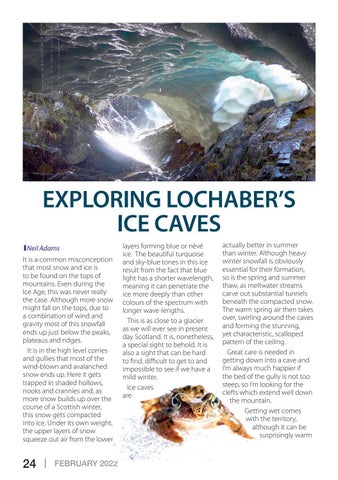

layers forming blue or névé ice. The beautiful turquoise and sky-blue tones in this ice result from the fact that blue light has a shorter wavelength, meaning it can penetrate the ice more deeply than other colours of the spectrum with longer wave-lengths. This is as close to a glacier as we will ever see in present day Scotland. It is, nonetheless, a special sight to behold. It is also a sight that can be hard to find, difficult to get to and impossible to see if we have a mild winter. Ice caves are

actually better in summer than winter. Although heavy winter snowfall is obviously essential for their formation, so is the spring and summer thaw, as meltwater streams carve out substantial tunnels beneath the compacted snow. The warm spring air then takes over, swirling around the caves and forming the stunning, yet characteristic, scalloped pattern of the ceiling. Great care is needed in getting down into a cave and I’m always much happier if the bed of the gully is not too steep, so I’m looking for the clefts which extend well down the mountain. Getting wet comes with the territory, although it can be surprisingly warm

| February 2022

Lochaber Life February 2022.indd 24

10/01/2022 16:46:07