3 minute read

20 years at Tanguro Field Station -- I. The founding

Sarah Ruiz, Science Writer and Editor

It was a controversial decision at the time. “The decision to set up on the Tanguro ranch almost drove a wedge through us,” recalls Tanguro founder, Dr. Daniel Nepstad. “We had a discussion that lasted two days.” the forests on their newly acquired Tanguro property—an amalgamation of previously-cleared cattle ranches they were in the process of converting to soy fields.

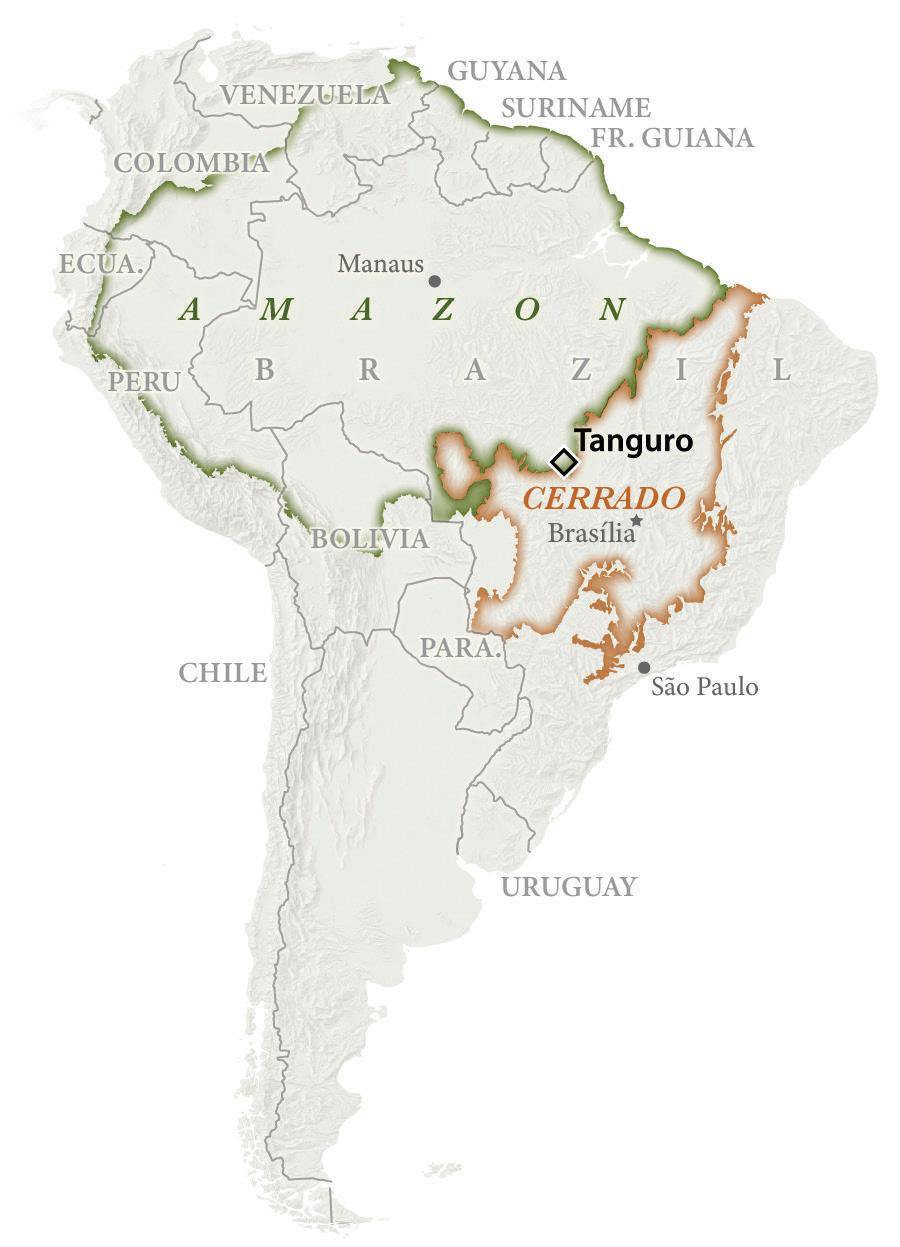

Fourteen years prior, Nepstad had established the Amazon program at Woodwell Climate (then the Woods Hole Research Center) in the state of Pará, studying the resilience of Amazon forests during long dry seasons. This work gave rise to a new research institute based in Brazil. In 1995, Nepstad co-founded the Amazon Environmental Research Institute (IPAM) in Belém to pursue policy-relevant science that could inform sustainable development in the Amazon. Woodwell Climate and IPAM began conducting simulated drought experiments and found that the rainforest, long thought to be immune to fire, lost that resistance during severe droughts. To investigate the implications of this, Nepstad realized, they needed a new experiment somewhere at the edge of the Amazon, where it’s drier year-round.

Nepstad had been spending more and more time in the state of Mato Grosso, fascinated by the expansion of soybean cultivation into the Amazon there. During his search for a new study site, Grupo Amaggi reached out with a remarkable invitation.

Grupo Amaggi was, at the time, the largest soy producer in the world, and soy was rapidly becoming environmental enemy number one, as hundreds of thousands of acres of forests fell to expand its cultivation.

The hope was that the research would demonstrate to the world what was really happening in these massive soy farms in the Amazon, providing data that could contribute to conversations around sustainable soy.

“Twenty years ago there were lots of discussions about environmental preservation and agriculture,” says Grupo Amaggi’s ESG, Communications and Compliance Director, Juliana de Lavor Lopes. “Could those two create a symbiosis? I think we knew [they] could work together, but could we prove that?”

“But Grupo Amaggi, a Brazilian company, wanted to get out in front of the issue,” says Nepstad. The prospect of losing a major market in Europe raised questions about the best way forward. In 2002 they set up the first system for tracing the forest practices of the farmers who sold them soy. And in 2004 they extended an invitation to Nepstad to study

For Nepstad, the invitation was also the perfect opportunity to run a controlled fire experiment in an ideal location. After much debate, IPAM decided to accept.

“There were a lot of folks worried that this would ruin our reputation, undermine our credibility with grassroots organizations—a lot of NGOs felt like we were selling out,” says Nepstad. “Some people accused us of being bought off by Grupo Amaggi.”

But Nepstad was very clear on the terms of the partnership. They would accept no money from the company other than what Grupo Amaggi invested in the buildings on the research station campus. And they would only support the farm’s activities as far as the science allowed. The research would accurately report the impacts of agriculture on the forest, with no restrictions on publication.

So in 2004, barely funded, but accompanied by a dedicated team of field technicians and researchers from the drought experiments in Pará—some of whom are still employed at the field station today—Woodwell and IPAM set up camp at Tanguro.

Header photo: A long, straight road into the horizon between fields and forest. / photo by Mitch Korolev