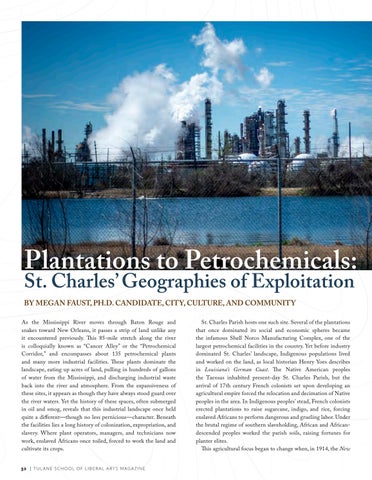

Plantations to Petrochemicals: St. Charles’ Geographies of Exploitation BY MEGAN FAUST, PH.D. CANDIDATE, CITY, CULTURE, AND COMMUNITY As the Mississippi River moves through Baton Rouge and snakes toward New Orleans, it passes a strip of land unlike any it encountered previously. This 85-mile stretch along the river is colloquially known as “Cancer Alley” or the “Petrochemical Corridor,” and encompasses about 135 petrochemical plants and many more industrial facilities. These plants dominate the landscape, eating up acres of land, pulling in hundreds of gallons of water from the Mississippi, and discharging industrial waste back into the river and atmosphere. From the expansiveness of these sites, it appears as though they have always stood guard over the river waters. Yet the history of these spaces, often submerged in oil and smog, reveals that this industrial landscape once held quite a different—though no less pernicious—character. Beneath the facilities lies a long history of colonization, expropriation, and slavery. Where plant operators, managers, and technicians now work, enslaved Africans once toiled, forced to work the land and cultivate its crops. 32 | TUL A NE SC H O O L O F LIBER A L A RTS M AG A ZI N E

St. Charles Parish hosts one such site. Several of the plantations that once dominated its social and economic spheres became the infamous Shell Norco Manufacturing Complex, one of the largest petrochemical facilities in the country. Yet before industry dominated St. Charles’ landscape, Indigenous populations lived and worked on the land, as local historian Henry Yoes describes in Louisiana’s German Coast. The Native American peoples the Taensas inhabited present-day St. Charles Parish, but the arrival of 17th century French colonists set upon developing an agricultural empire forced the relocation and decimation of Native peoples in the area. In Indigenous peoples’ stead, French colonists erected plantations to raise sugarcane, indigo, and rice, forcing enslaved Africans to perform dangerous and grueling labor. Under the brutal regime of southern slaveholding, African and Africandescended peoples worked the parish soils, raising fortunes for planter elites. This agricultural focus began to change when, in 1914, the New