6 minute read

Macro Pulse: The Norway Model Guiding Light for Namibia’s Oil Future

WHY EVERYONE SAYS NAMIBIA SHOULD FOLLOW NORWAY’S OIL MODEL

There’s a reason policy experts, journalists, and global investors keep saying, “Namibia should do what Norway did.” It’s not about copying blindly. It’s about learning from a country that transformed its oil wealth into one of the world’s most stable and prosperous societies, without falling into the traps that have ensnared many resource-rich nations.

Norway didn’t just strike oil. It struck a long-term strategy, one built on discipline, foresight, and world-class governance. That’s the path Namibia must now consider as it stands on the brink of an oil era that could define the country’s economic future for decades.

In recent years, Namibia has made some of the largest offshore oil discoveries in Africa, with estimated recoverable reserves of billions of barrels in the Orange Basin. These findings have dramatically elevated the country’s profile among energy investors and policymakers. But history tells us that oil wealth alone doesn’t bring development. Without the right institutions, it can deepen inequality, inflate corruption, and increase dependence on a volatile commodity.

This is why the calls to “be like Norway” are more than just praise or pressure. They are a timely signal. Namibia still has time to act, but not forever.

NORWAY’S OIL PLAYBOOK: INSTITUTIONS FIRST

Norway’s oil success wasn’t accidental. When the country began producing oil in the early 1970s, it had already committed to building the institutions needed to manage its newfound wealth. Three pillars underpin the Norwegian model:

Separation of Roles: The Ministry of Petroleum is responsible for policy. The Norwegian Petroleum Directorate regulates. Equinor (formerly Statoil) operates commercially. This separation of powers reduced rent-seeking and ensured that no single institution wielded unchecked influence.

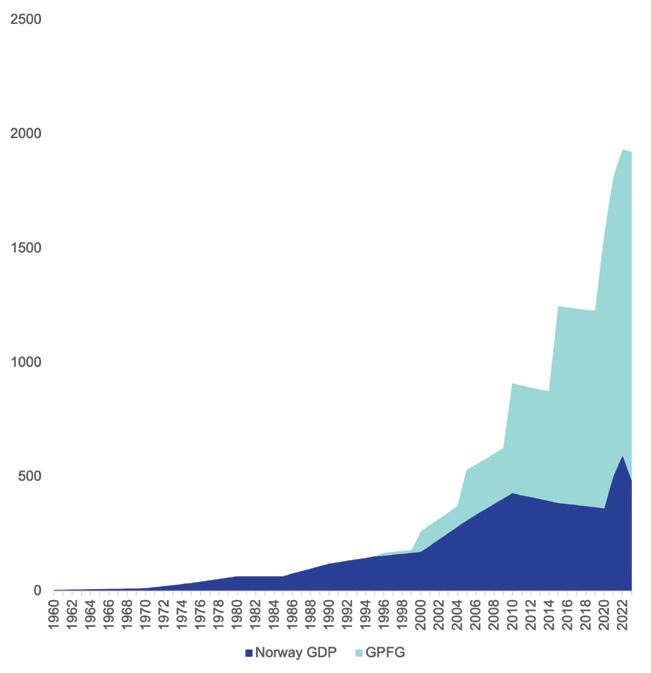

A Rules-Based Sovereign Wealth Fund: In 1996, Norway established the Government Pension Fund Global (GPFG), now valued at over USD 1.8 trillion. The fund invests oil revenues abroad, and the government can only spend about 3% annually, ensuring a real return to maintain intergenerational equity.

Transparency and Accountability: Norway ranks among the world’s least corrupt nations. All oil revenues, investment decisions, and exclusions are published in detail, ensuring that citizens are informed about where their country’s wealth is allocated and why.

NAMIBIA: A WINDOW OF OPPORTUNITY

Namibia finds itself at a rare turning point. Commercial production is still years away, likely not before 2029. However, oil exploration success has already begun to transform national expectations. Now is the time to lay the institutional groundwork. Once oil starts flowing, it will be much harder to resist political pressure to spend windfalls rapidly.

The government has taken some initial steps. It launched the Welwitschia Sovereign Wealth Fund in 2022 with N$270 million in seed capital. As of March 2025, it had grown to N$460 million. Namibia’s national oil company, Namcor, also holds minority stakes in exploration blocks to secure domestic participation.

However, essential risks and gaps remain. Namcor still plays both commercial and state roles, a conflict that undermines oversight. There is no legally binding fiscal rule to govern how oil revenues will be spent and Namibia is not yet a member of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), a global standard for revenue disclosure and accountability.

Without addressing these governance gaps, Namibia risks repeating the mistakes of other oil-producing states in Africa.

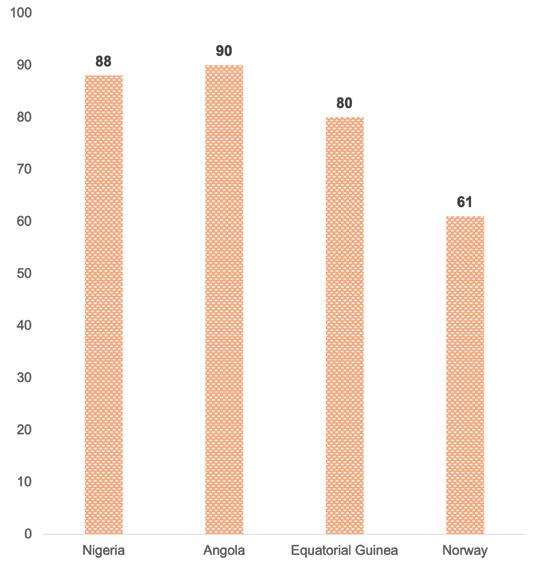

WHAT NAMIBIA MUST AVOID: LESSONS FROM OIL-DEPENDENT STATES

To avoid the pitfalls of resource dependence and emulate the Norwegian model’s success, Namibia must adopt a disciplined and transparent governance strategy anchored in the following five priorities:

Legislate and Strengthen the Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF): The Welwitschia Fund needs formal legal backing and a fiscal rule such as limiting withdrawals to 3% of the fund’s value to ensure long-term stability. This would avoid the kind of ad hoc spending that occurred during the 2023/24 SACU windfall and embed fiscal discipline before the oil revenue surge begins.

Separate Regulatory and Commercial Roles: Namcor currently manages both equity interests and state representation in oil projects. This dual mandate undermines objectivity. Namibia should follow the example set in the electricity sector, where the Electricity Control Board (ECB) regulates independently from NamPower.

Join the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI): Public trust and investor confidence would be enhanced through greater transparency. EITI membership would require Namibia to disclose contracts, revenue flows, and company ownership structures, limiting opportunities for corruption.

Align Oil Revenues with Diversification Strategy: Petroleum should finance transformation, not consumption. Revenues must be channelled into infrastructure, vocational training, renewable energy, and value-added manufacturing. Namibia’s green hydrogen projects and special economic zones in Walvis Bay and Lüderitz offer strong starting points.

Integrate Climate Transition into Energy Policy: As global demand for fossil fuels plateaus, Namibia must ensure oil investment does not lock the country into a high-carbon path. Revenues should be used to de-risk renewable investments, supporting a just and green transition. The establishment of the Green Hydrogen Council and partnerships with Germany and the EU are encouraging early signs.

Namibia is not the first African country to discover oil. But it is among the few to discover it at a time when the risks and policy lessons are widely known. Whether the country builds shared prosperity or repeats painful mistakes will depend on what happens before the first barrel is sold.

POLITICAL AND MACROECONOMIC RISKS: A REAL-WORLD WARNING

Oil discoveries inevitably raise political expectations. But if Namibia rushes into spending without the proper checks and balances, the result could be rising fiscal deficits, elite capture, and wasted opportunities.

Politically, the pressure to expand public spending could crowd out long-term planning. Without strong laws and oversight, future governments may be tempted to divert oil revenues toward short-term political objectives, such as inflated public wage bills, contracts for political allies, or unsustainable social programs.

Economically, Namibia could be vulnerable to the Dutch Disease. An oil-driven rise in the currency could hurt exports from agriculture, mining, and tourism, eroding jobs and competitiveness. Inflation may rise if too much oil revenue floods the economy without productive outlets. And with public debt already nearing 70% of GDP, the country cannot afford fiscal mismanagement.

Namibia must use oil to stabilise its balance sheet, not destabilise it. That means paying down debt, investing in productivity, and saving wisely through a strengthened sovereign wealth framework.

THE TIME TO ACT IS NOW

Namibia’s test won’t begin when oil starts flowing. It has already begun.

The country still has time to get the institutions right. But time is short. Expectations are rising. Investors are watching. And once oil money starts arriving, the pressure to spend will be intense.

By learning from Norway and avoiding the pitfalls of Nigeria, Angola, and Equatorial Guinea, Namibia can build a new economic future. One based not on boom-and-bust cycles, but on stability, equity, and long-term growth.

Because in the end, oil is not the prize. The prize is what Namibia chooses to build with it.