6 minute read

Forgotten Facts

from 10222021 WEEKEND

by tribune242

COLUMBUS

Advertisement

The statue of Columbus

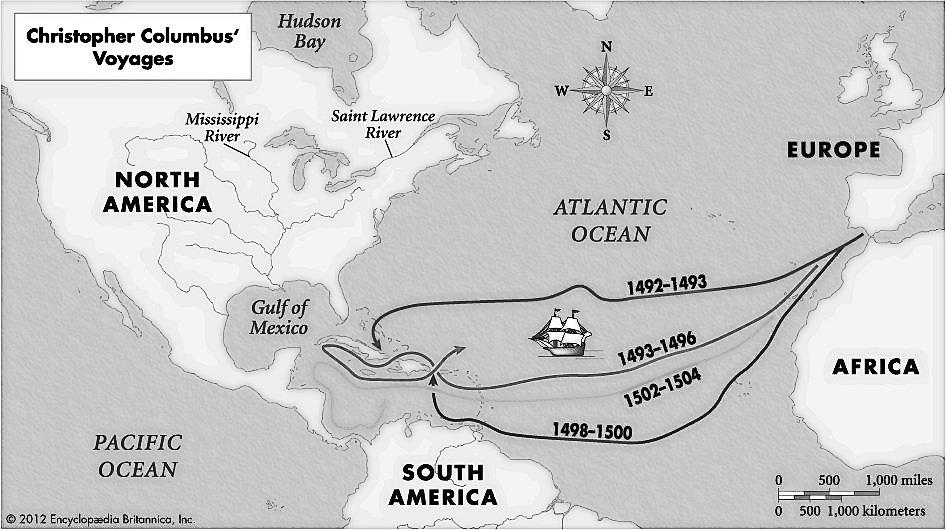

Iwrite this on October 12, 2021. Exactly 529 years ago today, the Santa Maria, the Pinta and the Nina dropped anchor at San Salvador and, as they say, the rest is history.

Whatever your reaction to the use of the word ‘discovered’, no one disputes the achievement of the captains and crews in opening ‘the New World’ to European awareness.

In 1492, that world was totally different to what we have today, but to blame Columbus for all the sins that followed defies logic. Is he, for instance, responsible for all that took place in what is now Haiti? As a French colony, Haiti was the envy of the world. Does one blame Columbus for what Haiti has become?

My father was considered an authority on Bahamian geography and history, and I heard him say over and over again that Governor James CarmichaelSmyth bought the statue (with his own money) and placed it where it has stood for almost 200 years. He also explained that once finished, the person(s) who commissioned the statue could not afford to pay for it, so Carmichael-Smyth picked it up at a good price and called it Columbus.

In the early 16th century, men did not dress the way the statue is dressed. It reminds me of one of the Three Musketeers. See the photo accompanying this article to see how Columbus would have been dressed.

Columbus and ‘his’ statue are priceless tourist attractions and we Bahamians are missing out on a lot of prosperity by not capitalising on it. It is generally accepted that San Salvador is an island in the Bahamas. Columbus Day is celebrated far and wide, and were we a part of the United States, every true-blooded American would want to see where ‘the Admiral of the Ocean Sea’ came ashore. San Salvador needs more infrastructure and deserves daily flights from Nassau so visitors can get to and from the island.

If it were decided that the statue is no longer needed in front of Government House, it should not be vandalised or destroyed. It could become the ‘meeter and greeter’ about 200 miles from Government House - a short hop for the man who criss-crossed the Atlantic Ocean.

PAUL C ARANHA

FORGOTTEN FACTS

fell in love with Evelyn Gardner – the daughter of Lord and Lady Burghclere.

In December 1927, Waugh and Evelyn Gardner became engaged and were soon known as “HeEvelyn” and “She-Evelyn”. Lady Burghclere was decidedly opposed to the marriage, stating that Waugh lacked moral fibre and kept unsuitable company. He was at the time dependent on a £4-a-week allowance from his father and tiny sums he earned from book reviews. Nevertheless, his Rossetti biography was published in April 1928 to a favourable reception. Rebecca West wrote about how much she had enjoyed the book. Less favourable, however, was the Times Literary Supplement’s references to him as “Miss Waugh”.

Duckworths refused to publish Decline and Fall, stating that the book was “obscene”. However, Chapman and Hill agreed to publish the work, giving enough encouragement for Waugh and Gardner to get married on June 27, 1928, in St Paul’s Church, Portman Square.

In September 1928, Decline and Fall was published to unanimous praise. The book was in its third printing by December and the American publishing rights were sold. Waugh received a commission to write travel articles in return for a free Mediterranean cruise which they embarked on in February 1929. The honeymoon trip was abandoned when Gardner contracted pneumonia in Port Said and was carried to the British Hospital there. The couple returned home in June, but a month later Gardner confessed that their mutual friend John Heygate had become her lover. A dismayed Waugh filed for divorce on September 3, 1929, and the marriage was annulled a few years later.

After Waugh’s divorce, friends noticed a new hardness and bitterness in Waugh’s outlook. Nevertheless, he soon resumed his professional and social life. He completed his second novel, Vile Bodies, and wrote a cynical article for the Daily Mail on the meaning of marriage. He resumed an itinerant practice of staying at the houses of various friends. He did not have a settled home for the next eight years. He was always welcome but developed a reputation as something of a sponge.

Vile Bodies, published on January 19, 1930, was Waugh’s first major commercial success. He was now able to ask for much larger fees for his journalism. He wrote regularly for Town and Country and Harper’s Bazaar, and turned out a hasty book Labels – a poisonous detached account of his honeymoon cruise with his wife, She-Evelyn.

In September 1930, much to the surprise and shock of his family, he was received into the Catholic Church. Waugh was influenced by his friend Olivia Plunket-Greene who had switched from the Church of England in 1925. Waugh later wrote: “She bullied me into the Church.” Much later Waugh admitted that life was “unintelligible and unendurable without God.” Another journey through British East Africa and the Belgian Congo resulted in the travelogue Remote People (1931) and the comic novel Black Mischief (1932). His next extended journeys into British Guiana and Brazil led to two further books, Ninety-two Days and A Handful of Dust – both published in 1934.

Despite accusations of obscenity and blasphemy from the Catholic Church in The Tablet, Waugh was determined to write a major Catholic biography. He chose the Jesuit martyr Edmund Campion as his subject and the book (published in 1935) caused more controversy because of its pro-Catholic and anti-Protestant stance. It won the Hawthornden Prize.

Waugh continued his travels and, following an unsuccessful trip to the Arctic in 1934, he returned to Abyssinia in August 1935 for the Daily Mail to report on the Italian-Abyssinian war, stating that Abyssinia “was a savage place which Mussolini was doing well to tame”. William Deedes, who was the eventual subject of his novel Scoop (1938), was openly critical of Waugh’s snobbery and felt that none of the other reporters felt they could keep up with “the kind of company Waugh liked to keep back home”. But Deedes admitted that Waugh’s courage was “deeply reassuring”. Waugh in Abyssinia (1936), covering his experiences, was dismissed as a “fascist tract” by the novelist Rose Macauley.

Back in England, Waugh’s circle of friends grew to include Diana Guinness, Lady Diana Cooper and her husband Duff Cooper, Nancy Mitford, the Lygon sisters, and Gabriel Herbert – the eldest daughter of the explorer Aubrey Herbert. Invited to the Herbert villa in Portofino in 1933, Waugh met the seventeen-year-old younger sister Laura. He was immediately attracted to her but realised he could not marry her because, as a Catholic, he could not re-marry while his first wife Evelyn Gardner was still alive. Desperate, he began proceedings for the annulment of his marriage on the grounds of “lack of real consent”. The case was heard by the ecclesiastical tribunal in London which had to wait while official papers were submitted to Rome. The annulment was not granted until July 4, 1936.

Waugh’s marriage proposal by letter to Laura Herbert in the Spring of 1936 was met with serious misgivings by the Herberts – an aristocratic Catholic family. But despite family hostility, the marriage took place on April 17, 1937, at the Church of the Assumption in Warwick Street, London. The bride’s grandmother bought Piers Court - a country house near Stinchcombe in Gloucestershire - as a wedding present. The couple had seven children, one of whom died in infancy.