2 minute read

Forgotten Facts

from 06182021 WEEKEND

by tribune242

The significance of boats and boating

PAUL C ARANHA

Advertisement

FORGOTTEN FACTS

Some time ago, I wrote about William R Johnson, Jr and his 1973 book “Bahamian Sailing Craft”. Today, I will expand on that article and throw in a few facts from elsewhere.

In 1973, there was still a large fleet of sailing vessels plying their trade between Nassau and the many Out Islands, carrying cargo and passengers. Many of these boats were built in places like Mangrove Cay, Andros. Some might be owned and operated by a single family, others by the entire settlement. A nearby supply of wood and a skilled carpenter with an eye for choosing the right trees to cut, were the first essentials of successful boatbuilding.

Boats connected Out Islands settlements to each other and to Nassau. To be sure of regular trade, a settlement needed boats. Those that that did not have their own boats were dependent upon others and it was not uncommon for weeks to go by, without any connection to the outside world.

Out Island life was, to a great extent, one of self-sufficiency, and a fleet of boats often made all the difference. In the 1920s, except for Nassau, more people lived on Mangrove Cay than on any other island. Andros islanders thrived on sponge-fishing, using their schooners and manpower to gather wool sponge from the sponge-beds west of Andros Island, known as ‘The Mud’.

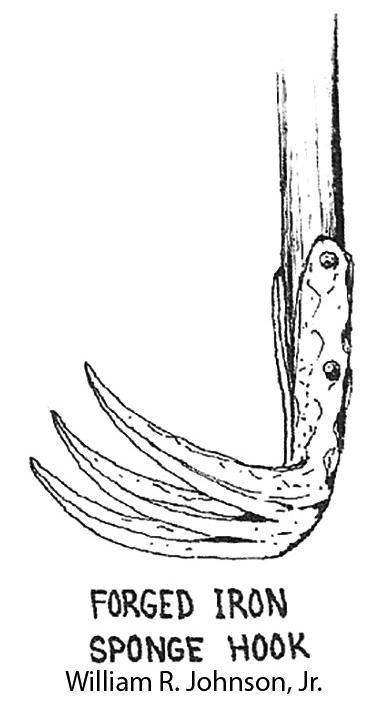

A schooner carried a crew of 10 to 20 men and six to eight dinghies. When they reached The Mud, the schooner captain would anchor his vessel, while the dinghies were put overboard, each with a crew of two. One man would scull and the other would be the spotter, who looked through a waterglass until he saw sponges then, using a special hook on a long pole, rip the sponges from the seabed.

Life on a spongeschooner was harsh. Work started at dawn and ‘hooking’ sponges continued until noon. After lunch, it was back to ‘hooking’, until the sun went down. It was ‘man’s work’ and the women were left behind to keep the home-fires burning, without seeing their men for many, many weeks.

At day’s end the sponges were stored aboard the schooner until there was no more storage space. At this point, the sponges were taken ashore and put into shallow kraals, where they would rot.

A few weeks later, the sponges would be washed, pounded, washed again, then strung in the ship’s rigging to dry. The schooner would then set sail for the Sponge Exchange in Nassau, a huge shed at the foot of Frederick Street, where they were sold to the highest bidder. Once graded and packed, the sponges were shipped abroad.