14 minute read

SPJST Participates in National Polka Festival

from Vestnik 2023.06.12

by SPJST

Friday and Saturday, May 27-28, 2023 • Ennis, Texas

The winners of the 2023 King and Queen Polka Dance Contest sponsored by SPJST on Friday night were Rick and Debra Halfmann. Runners up were Andrew Brenek and Tandi Schlittman. Polka Prince was Eli Gilbert, and Polka Princess was Audrey Andrad. Congratulations! SPJST members rode the first place float in the National Polka Festival parade on Sat- urday morning. Riders included 2022 District Three Royalty - King Preston Sullivan, Queen Madison Holland, Duke Luke Holland, and Duchess Jane Holland, all of Lodge 25, Ennis. SPJST also sponsored product information booths downtown and at Lodge 25, Ennis hall. The hall hosted Czech bands and a cultural program and served delicious food on Saturday.

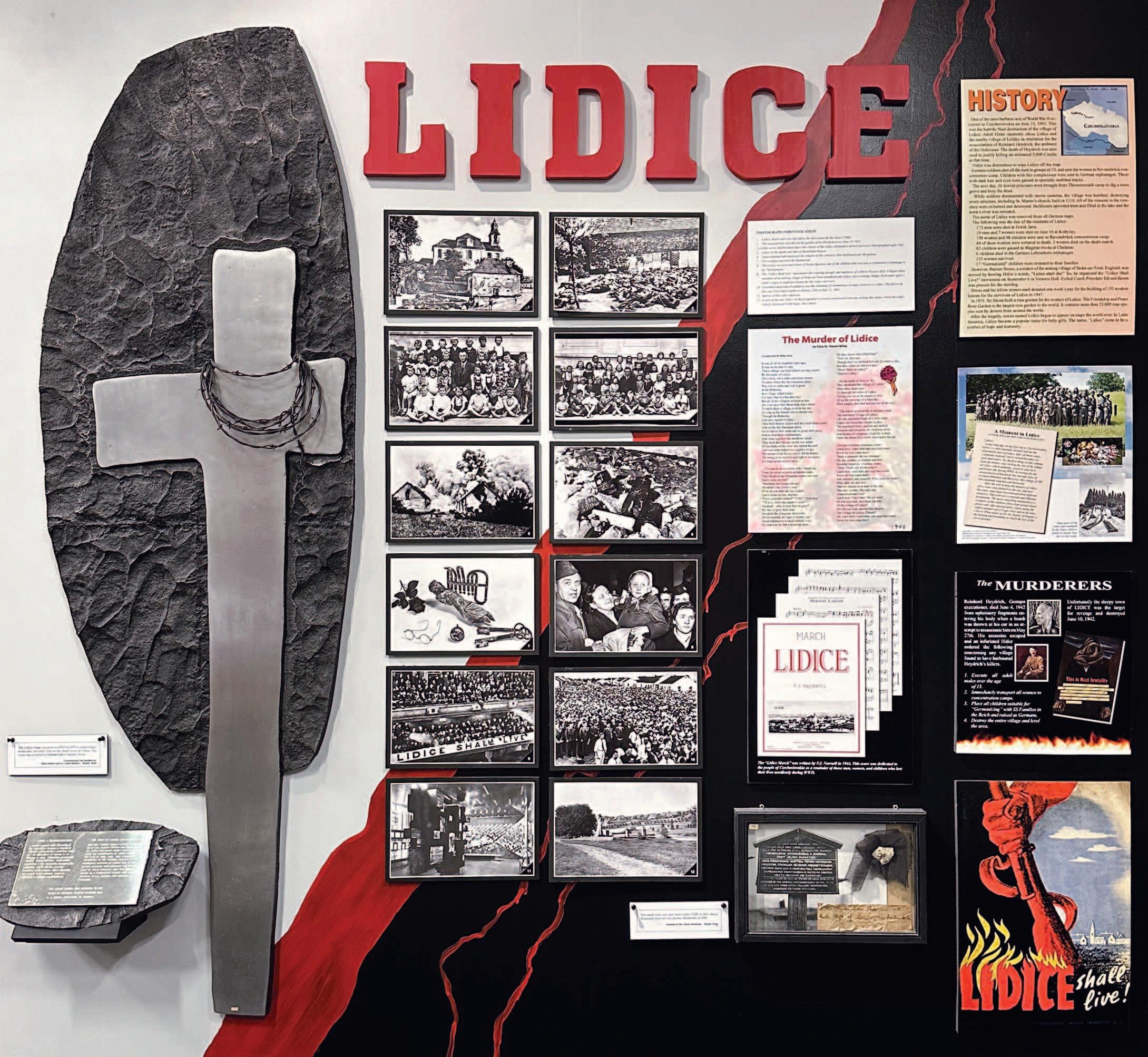

Massacre & Destruction of Lidice

For centuries, Lidice was an ordinary agricultural village, which belonged to the Buštehrad manor, located in a shallow valley of the Lidice Creek in the Kladno district sone 20 km west of Prague. The village is today, a quiet town that lies adjacent to valleys and of meadows, with a few stone ruins of a farmhouse and church, and a striking bronze sculpture of children.

The sleepy town of Lidice had been targeted because the Gestapo in Kladno had intercepted a letter belonging to a local family by the name of Horak, who had a son in the Czech army in Britain. This letter was labeled as “suspicious” and the ensuing action resulted.

What happened to Lidice on June 10, 1942, shocked the entire world: the German government announced that it had destroyed the small village of Lidice, Czechoslovakia, killing every adult male and some 52 women. All surviving women and children were then deported to concentration camps, or if found suitable to be “Germanized,” sent to the greater Reich. The Nazi’s then proudly proclaimed that the village of Lidice, its residents, and its very name, were now forever blotted from memory.

After the Munich Agreement of September 1938, Hitler’s troops occupied the ethnic-German border regions of Bohemia and Moravia (the Sudetenland). Soon afterward, Hungary received territory in southern Slovakia and Ruthenia. Czechoslovakia ceased to exist in March 1939 when Hitler occupied the rest of the Czech lands, and the remaining part of Slovakia became a Nazi puppet state.

Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia had tragic consequences for Lidice. In order to suppress the growing anti-Fascist resistance movement, security police chief SS Obergruppenfuhrer Reinherd Heydrich was appointed deputy Reichs-protektor in September 1941. During his short reign of terror, 5000 anti-Fascist fighters and their helpers were imprisoned.

The courts working under martial law were kept busy, and the Nazis even had people summarily executed without a trial in order to spread fear throughout the country. Many people throughout the Sudetenland died on the scaffold from Heydrich’ s persecution, that he earned himself the nickname the “Hangman”.

Edvard Benes, leader of the Czechoslovak government-inexile, together with Frantisek Moravec (head of Czechoslovak military intelligence), organized and coordinated a resistance network. Emil Hacha (third President of Czechoslovakia, 1938 to 1939), Prime Minister Elias (Czechoslovak general and politician and Prime Minister of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, April 27, 1939 to September 28, 1941), and the Czech resistance also acknowledged Benes’s leadership.

It was decided by Benes and Moravec, together with other political and military leaders in Paris and London, that some action must be taken if they wanted to retain the leadership of the exiled movement under their control. That action was to be the assas-

sination of Reinhard Heydrich.

Operation Anthropoid

The most significant act of resistance was the assassination of SS Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich, the Reich Protector of Bohemia and Moravia, “The Butcher of Prague”. The mission codenamed Operation Anthropoid was to be carried out by seven Czech patriots - Adolf Opaalka, Josef Bublik Jan Kubis, Jaroslav Svarc, Jan Hruby, Josef Valcik, and Josef Gabcik - who had trained with Polish forces in Britain.

May 27, 1942

Jozef Gabcik and Jan Kubis were airlifted along with seven soldiers from Czechoslo- village implicated in the Heydrich assassination: accounts, property records, livestock, agricultural machinery, and food stuffs. As the population was collected, they were relieved of their money, savings books, and jewelry. The communal registry was used to identify each citizen and their age. vaki’s army-in-exile. On May 27, 1942, Heydrich had planned to meet Hitler in Berlin. At 10:30 a.m., Heydrich proceeded on his daily commute from his home in Panenske Brezany to Prague Castle. Gabcik and Kubis waited at the tram stop on the hair-pin curve near Bulovka Hospital in Prague 8-Liben. Gabcik tried to open fire, but his Sten gun jammed. Kubis threw a modified anti-tank grenade at the vehicle, which severely wounded Heydrich. Heydrich was taken to Bulovka Hospital. He died eight days later from sepsis on June 4,1942.

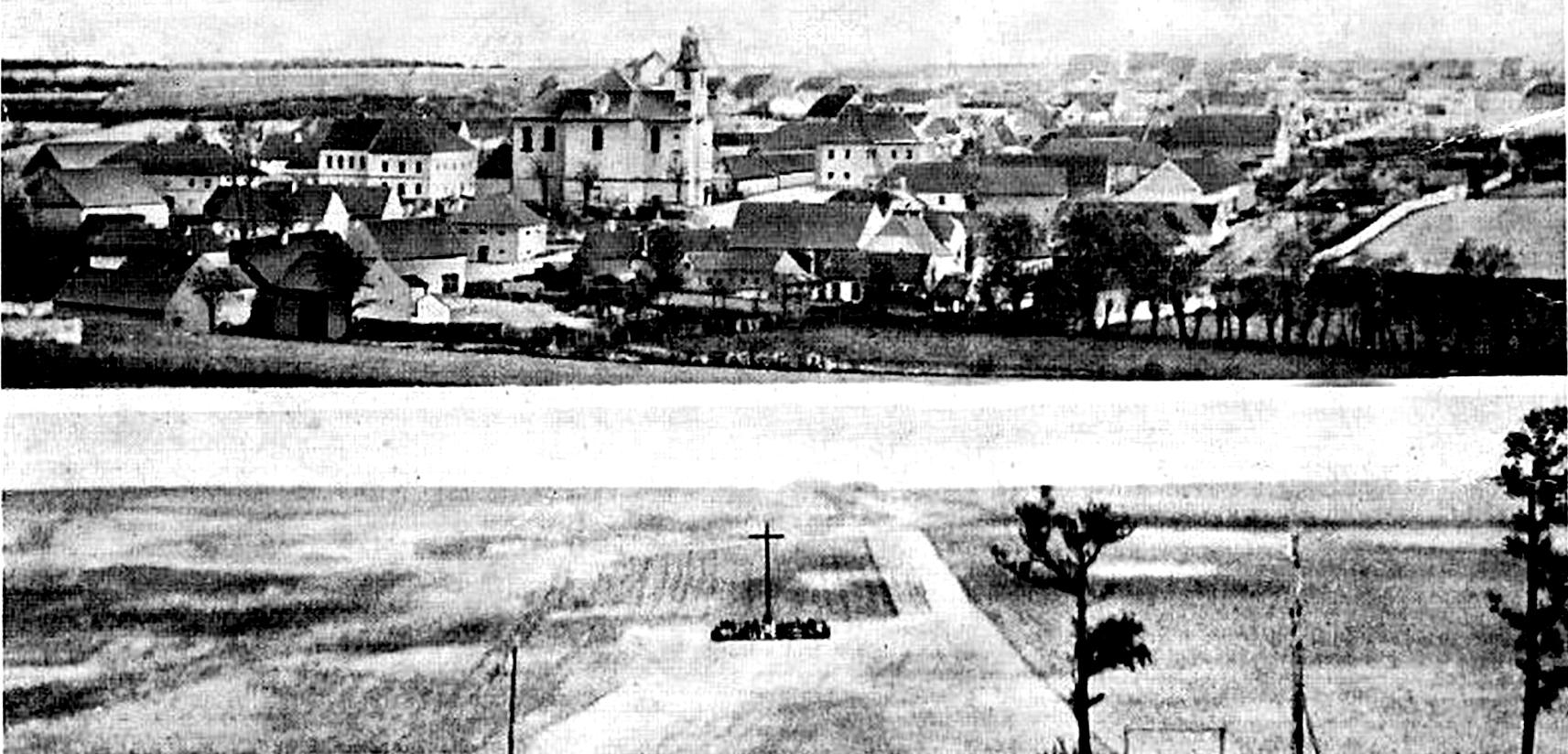

The village of Lidice. Top - before, and bottom - after its destruction.

• Execute all adult males over the age of 15.

• Immediately transport all women to concentration camps.

• Place all children suitable for “Germanizing” with SS families in the Reich and raised as Germans.

• Destroy the entire village and level the area.

The sleepy village of Lidice had been targeted because the Gestapo in Kladno had intercepted a letter belonging to a local family by the name of Horak, who had a son in the Czech army in Britain. This letter was labeled as “suspicious” and the ensuing action resulted.

Gestapo agents from Prague were joined in Kladno by two companies of police in battle-dress, and a squad of Security Police. The Security Police were under the command of SS-Hauptsturmfuhrer Max Rostock, who would carry out the executions.

In the village, the dead were left lying where they fell, and the newly brought out soon-to-be victims had to first walk past them and stand in front of them. The men were not blindfolded and were taken to the place of execution without bonds and shot by firing squad. This spectacle continued until there were 173 dead bodies lying in the Horak farm orchard. The next day, another 19 men who were working in a mine, along with seven women, were sent to Prague, where they were also shot.

Soon after Heydrich’s death, Nazi reprisals began when an enraged Hitler ordered mass executions of the Czech populace. Thankfully for many Czech civilians, Hitler’s threat never materialized; however, Karl Hermann Frank, now Secretary of State for the German Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, reported from Berlin that the Fuhrer had commanded the following concerning any

In the early hours of the morning, trucks filled with Security Police rolled into the small town of Lidice in the Kladno district. All men of the village were rounded up and taken to the farmstead of the Horak family on the edge of the village. Mattresses were taken from neighboring houses where they were stood up against the wall of the Horáks’ barn. Shooting of the men commenced at about 7 a.m. At first, the men shot in groups of five, but the SS commanders thought the executions were proceeding too slowly and ordered that 10 men be shot at a time.

Women and Children

The women of Lidice were no more spared than the children of the village. Separated from their children, most were transported to Ravensbruck concentration camp, where many died. Many of the children were sent to Chelmno - in today’s Poland - where they would be killed by exhaust fumes. Others were sent to Germany for re-education.

The well-organized Gestapo first secured anything of value – the town’s meager funds,

Empty houses were methodically searched, and items of value loaded upon trucks. The village’s St Martin church was plundered for its holy vessels. Any stillstanding walls were blown up. Bulldozers flattened the ruins, uprooted fruit-trees, and filled in the lake and even diverted the stream. Ploughs were driven back and forth across acres of rubble so that no recognizable outline should remain.

Lidice, 1945

The re-establishment of the village began soon after the liberation of Czechoslovakia in May 1945.

“The Murder of Lidice”

Edna St. Vincent Millay wrote The Murder of Lidice. Millay (1923 to 1950), was one of the most successful and honored poets in America. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, and the subsequent entry of the United States into World War II on December 8, 1941, Millay, wrote the ballad, The Murder of Lidice, in 1942 in response to the Nazi-led annihilation and destruction of the village of Lidice in German occupied Czechoslovakia on June 10, 1942. www.holocaustresearchproject.org/nazioccupation/heydrichkilling.html

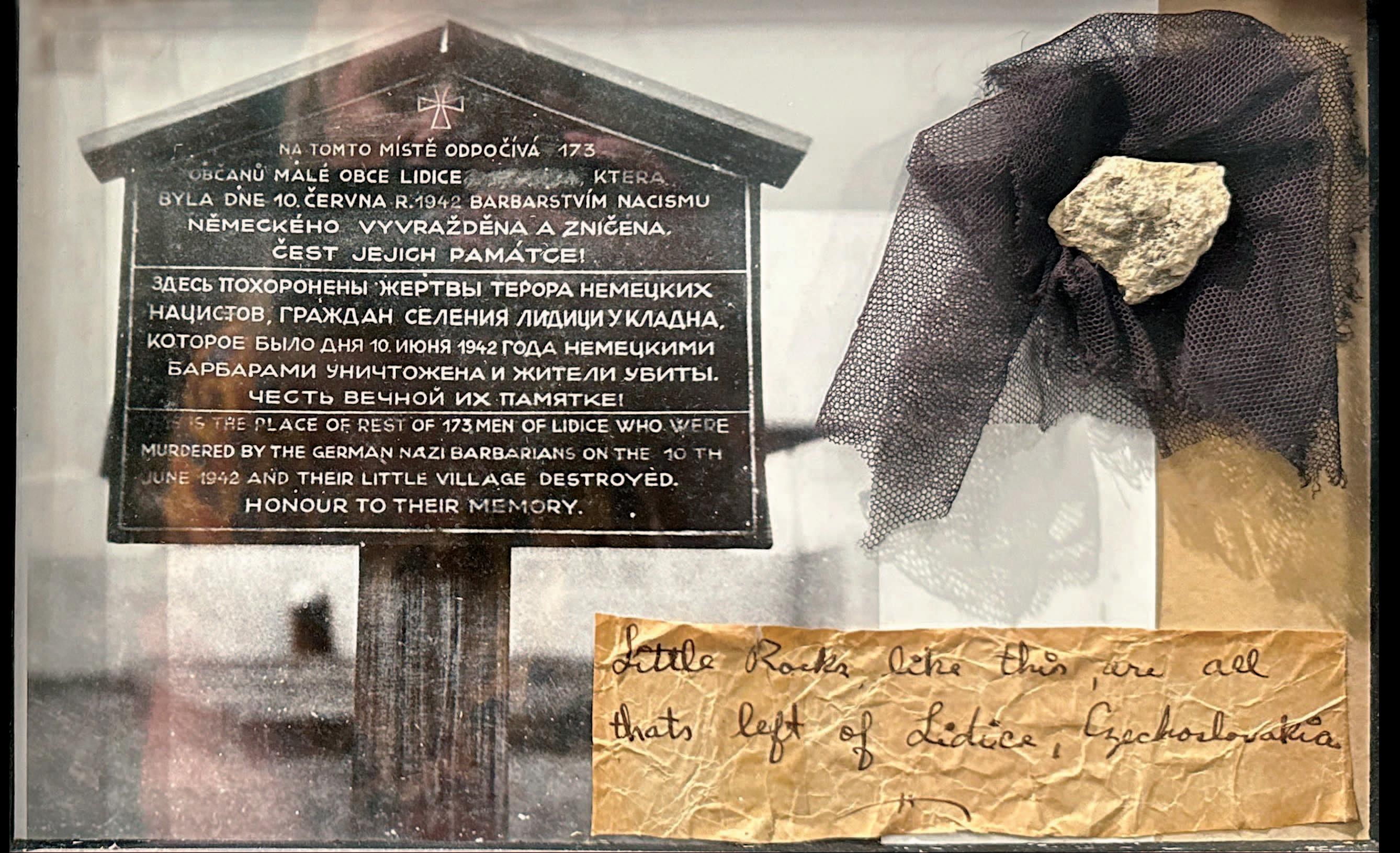

Czech Heritage Museum in Temple: Display pays homeage to Lidice

Czech Heritage Museum and Genealogy Center (CHMGC) has a permanent display in memory of Lidice and its people. The Mu- seum is located at 19 West French Avenue in Temple, and is now under the management of the SPJST Foundation.

Lidice site marker reads: This is the place of rest of 173 men of Lidice, who were murdered by the German Nazi barbarians on the 10th of June, 1942 and their little village destroyed. Honour to their memory. Handwritten note on yellowed piece of paper: Little rocks like this are all that’s left of Lidice, Czechoslovakia.

I am attaching an old newspaper article from the Dallas Morning News published in August 1968. It is based on the memories of Lois Sager Foxhall, a reporter for the Dallas Morning News. She is recalling a Czech woman who was coming to the United States after World War II. The woman used the name Lisa and had been active in the Czech underground, saving the lives of 24 American Air Force pilots and crewmen. I thought that it would make an interesting reprint for the Vestnik. I researched the author Lois Sager Foxhall, who is now deceased.

Blessings!

Georgia

Dallas Morning News, 1968

By Lois Sager Foxhall

I have never been able to forget Lisa, the Czech girl, and I have tried. Especially, I remember her now.

While her countrymen again die in the streets in military occupation likened by them to Hitler's invasion in 1938 and try to subvert a coup called another Munich, I am haunted by Lisa, as I have been, off and on, for 23 years.

Lisa was one of six with whom I shared a stuffy cabin on an archaic troop ship on my return from ravaged postwar Europe. The Nazis were beaten into the rubble. The Russians were our allies.

And, though I was a Josephine-go-lately, I felt the flush of victory, the weary relief of thousands of tired soldiers cramming into the old troop ship to go home to loved ones, family, clean sheets and eggs.

The battle was over. For them, no more fighting and waiting. For me, no more cigarette lines, rationed tires and bacon and the bitter death of heroes.

The Czech girl smiled wistfully at us. Holding her small duffle bag, she waited while we scrambled for a sad choice of dingy bunks. We blurted introductions: The French girl was Hani Richon, her blonde hair not yet grown out from its little boy's crop. In her bag was a medal given her by De Gaulle for her work in the Resistance, she said. Now she was the bride of an American soldier, going to live with his family in Michigan.

There were three USO stragglers - Jane Tilford, a willowy eastern girls" school drama student, wan and embarrassed over the common GI ailment that kept her hospitalized while her troupe went home earlier; Kay Kingsman, a pretty, throaty singer who had gone to Germany in search of Jewish relatives no longer there; and Eileen Beetlebaum, who had false black eyelashes, Jane Russell's bosom and tiny legs, famous, she said, as the "Beetle" for a spinning top and almost topless dance.

I was a correspondent for The Dallas Morning News, in Texas.

The Czech girl, said simply, "Call me Lisa. I cannot tell you my name. I still have relatives in Czechoslovakia." Long, reddish blonde hair, smoothly brushed, fell over the padded shoulders of a doublebreasted suit, cut from an old Air Force uniform "Czechoslovakia is liberated," I protested her secrecy.

"You are a journalist. Did you go there?" I shook my head, felt a strange stab of conscience. I wondered why I had been so anxious to go home and had given up so easily my attempt to get a visa or military orders after two months being told "Nyet" by the Russians and shrugged off by the military. Lisa’s green eyes looked inside me.

I remember the tragic men and women in displaced persons camps who begged not to be sent home to nations occupied by Russia, the Russian girl I met in the Vienna International Officers Club who asked about cars, radios and "refreezeerators," invited me to lunch, then disappeared, and the children freed from concentration camps whose adoption in America Russia blocked.

It's an old familiar pattern now, but then a prick in our balloon of elation, a prod to our sense of relief.

I tried to forget Lisa's remark and recapture my excitement of going home.

Up on top deck, we cheered with the GIs crowding the rail and waved to France, as the doughty George Washington, carrier of troops in World Wars I and II, inched its way out of the gray, dismal harbor of LeHavre. It was bitter cold. Fog hung barely above us.

We slipped past a giant black and white sign, TEXAS - 2,500 miles. The soldiers cheered. Lisa flashed a grin at me. We were the first ship in the wake of a North Atlantic storm that had broken a smaller Liberty ship in half. By the time we were back in the cabin, the deck had begun to roll.

Hani began to cry. "My husband's family will not like me. I will never see the Champs Elysees again."

"Let us not be sad," Lisa soothed. "We are on our way to America and Texas. So long we lived with death. Now, we will live with life."

Hours later, we joined the continually moving mess line. We weaved our way down through decks layered with 6-deep hammocks of GIs, some already seasick. We stepped over duffle bags and soldiers. Suddenly, I realized I did not have my sea legs. Hardly anyone did. Back in the bunks, Lisa held our heads, gave us dramamine. We slept.

Next day, our big ship bobbled up and down like a cork, pitched and heaved between green waves rolling higher than skyscrapers, spewing torrents of foam. We sipped tea, nibbled apples, sat on deck to feel the cold wet wind in our faces, at Lisa's suggestion, trying desperately to get back our sea legs. Our charted five-day crossing began stretching into 14, the number of hours it had taken to fly to Europe.

It was days later, even in the intimacy of shipboard conversation, before we pieced together Lisa's story, then only with the help of an Air Force general we met in the captain's cabin.

During the war Lisa, her father and younger brother, working with the massive Czech underground, had saved one by one, the lives of 24 American Air Force pilots and crewmen, shot down in raids over the Ploesti oil fields and Skoda iron works. (Two were Texans.)

Now three Air Force officers whose lives she had saved had managed to send her to America for a college education. She hoped to be a teacher like her father. He was a friend of Masaryk and Benes, Czech freedom leaders in exile.

When I asked to write her story, Lisa said with amazement, "But you are naive, the Russians marched in when the Germans marched out. On our last rescue mission, two Russian soldiers joined my father, my brother, and me. They would not let us out of the house until our American friends came for me. My father and brother are still under their 'protection."

The Czech girl was younger than I in years. In experience and wisdom, she was centuries older. At an age when I was playing dolls and hopscotch Lisa, her mother dead, began working with her father in her small country's fierce resistance to German occupation. At the age when I was trying to learn to spell her country's name, she was mastering English, Russian, German, and French, and discussing with her father the affairs of troubled Europe. While I was cheering a football team and dancing, she was crawling through tunnels, hiding in stables, sneaking through paths to bring Allied soldiers to safety.

Lisa, who would not tell her name, gained the confidence of everyone she met. She roamed the heaving ship like a curious puppy off its leash. She listened, sympathized, comforted, chatted, talked seriously, laughed and stared at the vast eternity of stormy sea.

At the height of the storm, when everyone was ordered below for safety, Lisa disappeared. She returned to the cabin hours later, drenched, her hair tied in a wet scarf. She had been up near the prow. It was glorious, she said, fierce and free.

Lisa, like the sea, was a symbol of her nation's freedom loving people, Bohemian, Moravian, and Slovak, centuries before they were molded together into one nation, Czechoslovakia, they fiercely defended their rights to religious, intellectual and territorial liberty. Their land, the land, the heart of Europe, has been fought over by larger, militarily stronger neighbors for centuries.

Now, this nation of 14 million people squeezed in between Russia, Poland, Hungary, Austria, and Germany, is again a symbol in the eternal struggle of the weak against the strong, of intellect and cunning against military might.

In a tattered PX notebook in the bottom of a desk drawer, I found these defiant words of Lisa's scribbled 23 years ago:

"A nation can sleep with the enemy, get out of bed a virgin, stab him in the groin and write FREEDOM on the wall with his blood."

Finally, the storm bated, and the George Washington once again weighted anchor outside New York harbor waiting to dock in the morning. We watched the twinkling lights in New York's skyline, tried to point out the tiny, faint glow of the Statue of Liberty for Lisa.

In a circle of GIs the Beetle spun like a top, Kay sang a throaty love song, Jane did a comic imitation. But it was Lisa who cast a spell with a plaintive song in Czech that sounded like a gypsy's sad cry under the moon and stars.

Afterward, Hani pleaded, "Stay with me in this country and marry an American." Lisa laughed. “I must go back to my own country. I will teach our children what I learn here about freedom. And I must help my brother and my father. Freedom is in the soul. I could not be free unless I help them also to be free."

—SPJST—

Czech Cu l tural Calendar

Hours

of Operation

Czech Heritage Museum and Genealogy Center (CHMGC), 119 West French Avenue, Temple. Hours: Open Thursday, Friday, and Saturday, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Admission is $4 for adults, $3 for those 60 or older, and $2 for kids, 12 and under. Every First and Third Tuesday Evenings: Tarok Parties—All ages and anyone interested are welcome. No admission or fee. Awardwinning tournament champions Jimmie and Carolyn Coufal not only teach beginners, but also help experienced players increase their skill. For Museum information: tours, happenings, and activities, call: CHMGC 254-899-2935 (can leave a message); email czechheritagemuseum@gmail.com; find them on Facebook; or visit the Center’s website https://czechheritagemuseum.org

Monday through Saturday

Czech Center Museum Houston, 4920 San Jacinto Street in Houston, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Exhibits. Experience the culture, art, music, and stories of many Czechs, Slovaks, and people of all cultures who left their country to seek liberty and democracy in America. Beginner Czech Lessons: Monday evenings, 6:30 to 7:30 p.m. Conversational Czech hour - Saturdays, 1 to 2 p.m. Bring a friend or neighbor and come practice your Czech! Not a member? Join today for early access to concerts, movie nights, lectures, and events at CCMH as well as free Czech language lessons and monthly membership socials. Monthly Movie Night: CCMH has reinstated monthly movie nights. CCMH, 4920 San Jacinto Street in Houston. For information, call 713-528-2060; or visit czechcenter.org

July 13

Night at the Museum—at Czech Heritage Museum, 119 West French Avenue, Temple, 5 to 7:30 p.m.: Part of a spring / summer series to establish the museum as a community meeting / networking place with regularly scheduled activities including performances. Admission free. Public is invited. For information, contact organizer Brian Vanicek at vanicek@spjst.com.

76501