all about the water

October 2019

all about the water

October 2019

Marina: (912) 897-2896

Boatyard: (912) 897-1914

606 Wilmington Island Road

Savannah, GA 31410

www.sailharbormarina.com

CREW

Publisher/Editor

Amy Thurman amy@southerntidesmagazine.com

Around the Reef Columnist

Michelle Riley michelle.riley@noaa.gov

Ebb & Flow Columnist

Trey Leggett info@southerntidesmagazine.com

The Bitter End Columnist

Captain Daniel Foulds dan@southerntidesmagazine.com

Consulting Naturalist

John "Crawfish" Crawford crawfish@uga.edu

Contributing Writer

Erin Weeks weekse@dnr.sc.gov

Copyright © 2015-2019

All content herein is copyright protected and may not be reproduced in whole or part without express written permission.

Southern Tides is a free magazine, published monthly, and can be found at multiple locations from St. Marys, Ga., to Beaufort, S.C.

(912) 484-3611 info@southerntidesmagazine.com

Visit us on social media: www.issuu.com/SouthernTidesMagazine.com Facebook.com/southern-tides-magazine Instagram @ southerntides_mag

Southern Tides Magazine is printed by Walton Press, Monroe, Ga.

Subscribe to Southern Tides: Visit www.squareup.com/store/ southern-tides-magazine $25 for one year/12 issues. (plus $1.15 credit card processing fee) Thank you for your support!

Letters to the Editor:

We love hearing from you! Questions, comments, ideas, or whatever you'd like to share, please do!

Send your thoughts to any of our email addresses listed above.

• 4,000 feet

Marina Amenities

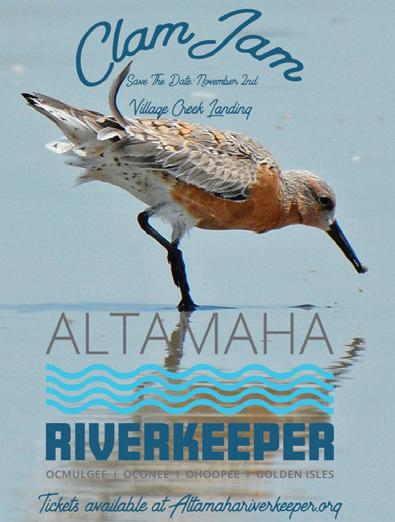

elcome to the first Southern Tides October Oyster Issue!

Fall is here, which means it's time for fishing, fire pits, and football, and before long, it’ll be time to trade our summertime lowcountry boils and barbecues for that other lowcountry social rite we look forward to every fall – the oyster roast.

It isn’t just about eating those delicious little morsels. It’s the blazing fire and scents of woodsmoke and marsh mud, the chill in the air, laughing and sharing stories with people you know and people you don’t, the camaraderie of standing around a table with those same people, and the little thrill of victory as you pop open a shell, exposing the pearly white and purple interior, encasing that perfectly roasted oyster. There's just something visceral about it. As you attend oyster roasts this fall and winter, take a moment (or several) to savor each of those sensations!

To honor this symbol of our lowcountry and coastal lifestyle and environment, we’ve dedicated this issue to oysters. If you didn't already know it to be true, you'll see from these pages that we here in the lowcountry revere the oyster.

From oyster farmer Frank Roberts quoting a French poet in Kissing the Sea on the Lips (page 15), to a contractor who designed his own oyster camouflage pattern (page 20), we hold these bivalves in high esteem. (OystaFlage - this just makes me smile every time I see it!)

Ingredients

• Several bushels of fresh oysters (from your favorite location)

• A hot fire

• A sheet of tin, or a grate, and a burlap bag (or a steamer)

• A big table and a couple clean trash cans

• A stack of clean shop towels and/or shucking gloves

• A couple dozen oyster knives

• A box or two of saltines (optional)

• Cocktail sauce, Frank’s Mignonette (see page 19) or hot sauce

• Cold beer or other beverage

• A good mix of people you know and people you don’t

Roasting Directions

• Place tin over a low fire or hot coals with a little clearance.

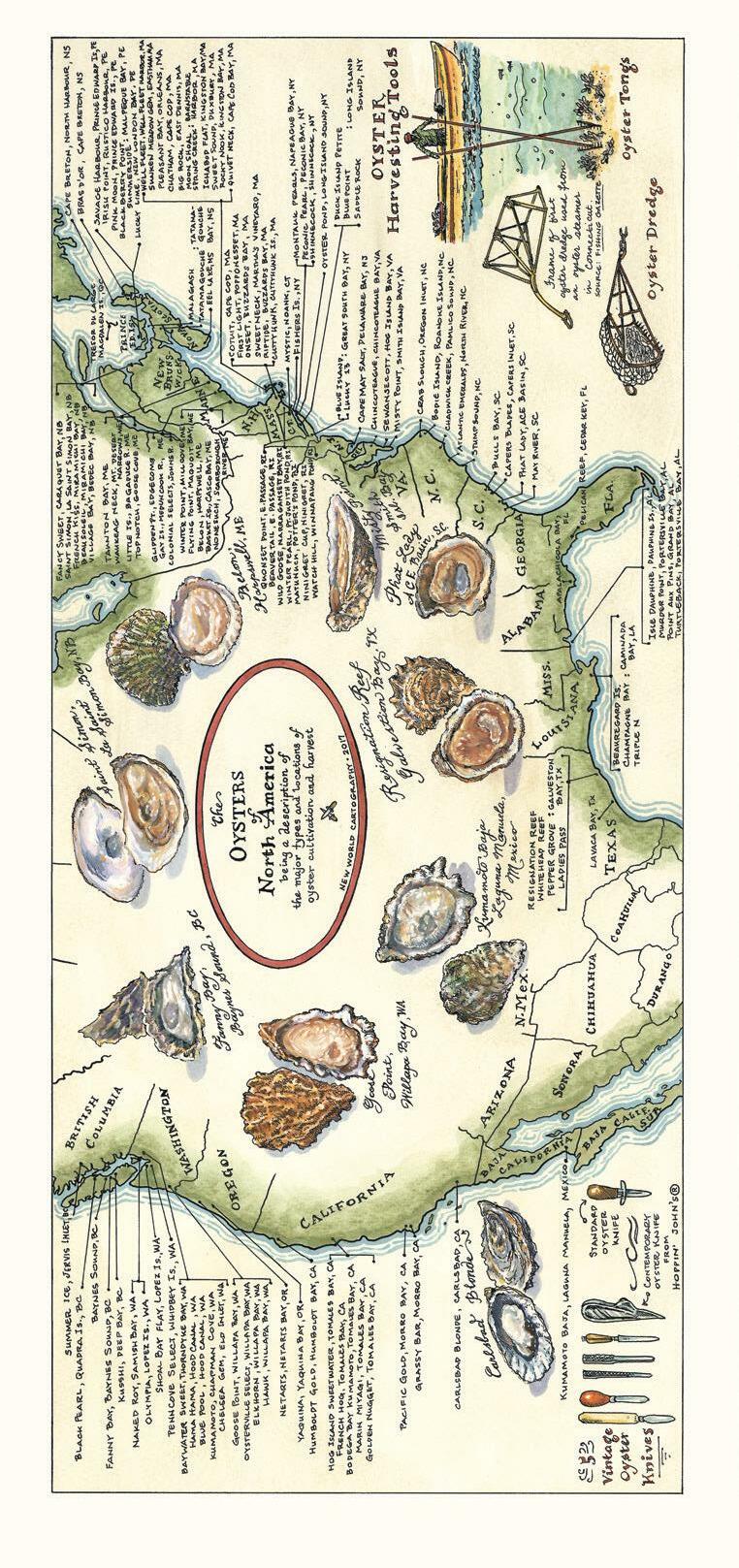

We also have an oyster map from New World Cartography (page 28). Yep! An oyster map! I love maps and charts, and I love oysters, so this is win-win in my book. (As you look it over and read the story, consider how amazing it would be to have a map of your favorite location or property.)

It really hit me as I wrote and/or edited these articles this month, just how deeply rooted oysters are in our coastal culture and our collective psyche. Dan and I, who are only just getting to know each other and hadn't discussed it prior, used very similar language in our oyster roast descriptions. Everyone I spoke with about oysters in putting this issue together expressed sentiments about the oyster as a symbol of everything they love about the lowcountry.

In addition to being key components of our culture, oysters are critical to our coastal ecosystems, through filtering water, providing habitat for other marine species, and stabilizing the banks of our creeks and rivers. This issue covers environmental and economic benefits too. Take a look at the back cover, where Zulu Marine offers information on living shorelines – a service they offer with amazing benefits for our coastal environment. Oyster shell recycling information and locations can be found on page 13.

South Carolina has a strong oyster aquaculture program going, and Dan spent a day learning about Georgia's developing program too. Learn more about it on page 24 in Positioned for Growth.

We plan to make this an annual issue, so please reach out and share your thoughts and ideas for next year. In the meantime, enjoy the read! Maybe I'll be the one standing next to you at an oyster roast sometime soon!

See you out there!

Amy Thurman Editor in Chief• Shovel oysters onto the tin and top with a soaking wet burlap bag. (If using a steamer, follow directions for use.) Check oysters after a bit and watch for them to just start to peek open, then use the shovel again to carry them to the table.

• Repeat as long as you have oysters.

Eating Directions

• Gather ‘round the table with an old friend at one shoulder and a potential new friend at the other and get to shuckin'. Using a towel or a glove, grab an oyster (or cluster) from the pile and turn it until you find a starting point. Start with the easiest – the shells you can separate with your hands, to rescue those oysters from getting too cold. Use the knife to separate the oyster from the shell and eat it as you prefer, whether that’s straight from the shell or on a cracker with the sauce of your choosing.

• Next work your way around the cluster to the rest of the oysters. Place your knife in the divot next to the hinge and with a gentle push and twist, pop the shell open, remove the oyster and enjoy.

• While all this is going on, sip your beer, listen to stories and tell your own, reconnect with old friends and make new ones.

• Periodically toss your shells in the bin for later recycling, and make way for others to join the table too.

• Be sure to thank your cooks and don’t let their drinks run dry.

• When the oysters are gone, gather ‘round the fire and continue with the beer sipping and storytelling.

• Repeat this recipe often throughout the winter for great eats and great memories!

By Trey Leggett

By Trey Leggett

In typical southern fashion, here we are in October and still having above normal temperatures. In September we only had a few days of cool weather, but just like that they were gone and we were back into the mid- to upper-90s. I can promise you one thing though, life and season cycles may slow down, but they won’t stop completely. October is the beginning of fall and with that comes deer gun season, big bull redfish, and a better than average spotted sea trout bite.

Hunting Notes

So far, my crew and I have struck out during bow season for white-tailed deer. The work has been put in on the property, stands and blinds are strategically placed, and signs are on the ground and on the trail cameras. We’re just waiting on those cooler temps to hopefully change the deer’s travel habits.

I had some issues with my bow early on … to tell the truth it was actually issues with my shooting. That has been corrected and upgraded and I’m excited to deer hunt this entire season with my bow (except my hunting trip to Texas).

Fishing Notes

I’ve seen reports of anglers fishing the beaches and reeling in big bull redfish. A good setup for this type of fishing would include:

1) A 7- to 12-foot medium to medium-heavy rod (as long as it has a fast tip)

2) 30-pound braid or monofilament line

3) A 7-foot monofilament leader in the 80- to 100-pound range

4) A 6/0 to 9/0 circle hook

5) Three ounces of weight, or more depending on the speed of the water current. A pyramid or spider sinker is best.

Cut mullet makes for a tasty bait for the big reds, but cut whiting or ladyfish are even better. A good sand spike that’s properly anchored in the sand is a must unless you want to be constantly fixing it or chasing your rod into the water when a big fish slams it. Cast out as far as you can, then sit back and enjoy the beach until you get a bite.

September, October and November are my favorite times of the year to target spotted sea trout, aka speckled trout. I enjoy throwing soft plastic swim baits and imitation shrimp to illicit bites, but I’m not above tossing a live shrimp or mud minnow with a khale hook under a popping cork with about a 2 ½-foot to 3-foot leader. Using a popping cork rig is also a great way to get kids involved in fishing fun. Speckled trout are a very tasty fish and are perfect for when you want to do a fish fry with some friends or family.

With this being the October Oyster Issue of Southern Tides, I would be remiss if I didn’t include something about oysters. I like to eat oysters raw, steamed, or baked. I like them with or without hot sauce. I’ve heard they’re some sort of aphrodisiac, but I don’t know much about Greek Mythology, I just like to eat oysters!

Stay safe and tight lines.

Trey Leggett is an outdoorsman sponsored by Engel Coolers and Hobie Polarized sunglasses. Email: info@southerntidesmagazine.com

Photo contributed by Frank Roberts

Photo contributed by Benton Parrott

Photo contributed by Marty Mood

Trey Leggett is an outdoorsman sponsored by Engel Coolers and Hobie Polarized sunglasses. Email: info@southerntidesmagazine.com

Photo contributed by Frank Roberts

Photo contributed by Benton Parrott

Photo contributed by Marty Mood

Over 30 years ago, the United Nations proclaimed the first Monday in October “World Habitat Day” and took an important step in promoting the idea that every creature deserves a place to call home. While habitat can be defined as “the place or environment where something naturally or normally lives and grows,” I personally prefer the simpler description, “the place where something is commonly found.”

These definitions may be self-explanatory, but have you ever stopped and thought about what your habitat truly is? For some, it’s their hometown, community, or family home. Most days, I’d describe my favorite coffee shop, or any coffee shop for that matter, as my habitat! Here at Gray’s Reef, we have a special type of habitat that we pride ourselves in. Its environment boasts its own distinct personality and provides a unique dwelling for all those that reside in it.

Gray’s Reef is one of the largest near-shore “live bottom” reefs, a term that sets our reef apart from the others. Natural live bottom reef helps identify what kind of habitat Gray’s Reef provides. Our hard, sedimented, rocky seafloor is different from the typical coral reefs you’re used to seeing in travel brochures. From its gravelly crevices to its vibrant floor bed, this stony jungle gym under the sea houses marine life of all shapes and sizes. These live bottom neighborhoods are teaming with invertebrates and small organisms that serve as the foundation for all other occupants. Sea urchins and

anemones sprawl across the ground, while nurse sharks, loggerhead turtles, and moray eels seek shelter under the jutted ledges.

An extremely diverse habitat can be found within the actual reef itself. Rock-strewn caves and tunnels hide an octopus in plain sight, while animated fish weave through colorful shrubbery as they teeter the line between predator and prey. If you find yourself searching through the corals, you’ll notice arrow crabs scuttling across sponges and sea stars lounging among invertebrates. The colors, shapes and intricacies you’ll find hidden throughout our live bottom habitat will have you seeing technicolor in a sea that is neither crystal nor clear.

If World Habitat Day wasn’t enough, October 23rd marks the 47th anniversary of the National Marine Sanctuaries Act. Not only do we get to celebrate amazing habitats such as Gray’s Reef, we also applaud and commemorate the historic moment when national marine sanctuaries were signed into existence. Thanks to the Marine Protection, Research, and Sanctuaries Act on October 23rd, 1972, our government piloted a new era devoted to oceanic protection and marine conservation. You have to wonder, if it wasn’t for that important shift within our government, the sanctuaries we know and love may not be accessible to us today.

By the early 80’s, six marine sanctuaries had been sanctioned within the United States. Our very own Gray’s Reef was one of the first aquatic ecosystems to be a part of the National Marine Sanctuaries Act alongside USS Monitor, Key Largo, Channel Islands, Point-Reyes Farallon Islands, and Looe Key. These habitats that border both the East and West coasts stood out to researchers and conservationists, making them a haven for education and excursion. In studying and protecting these newly authorized sanctuaries, it paved the way for continued ocean exploration, leading to the discovery of our current 14 existing national marine sanctuaries encompassing over 600,000 square miles.

As we look back at all history has given us, we feel hopeful and inspired for what is yet to come. With every quick dash of a black sea bass, to the rhythmic stroke of a jellyfish, Gray’s Reef is privileged to be a part of such a historical and influential establishment that devotes its existence to the continuous appreciation of the underwater world. As we celebrate these significant moments in our oceanic journey, we will let that resilience ripple into future endeavors as we continue to change history, one wave at a time.

For more info, email: michelle.riley@noaa.gov

Live bottom at Gray's Reef. Photo by Greg McFall/NOAA

The old adage about only eating oysters in months with R in the name is not quite accurate here in the South, where water temperatures are warmer. Not only because oysters spawn during warm spring and summer months, allowing populations to thrive and reproduce, but also because spawning is a lot of work and tired oysters aren’t very flavorful. The bacteria v. vulnificus and v. parahaemolyticus are more likely to occur in warmer waters as well, but it’s important to remember that it can occur at any time, which is why you should only eat harvested oysters that have been stored at temperatures below 45 degrees.

With oyster season is underway, many coastal residents are enjoying these tasty treats in a variety of delicious ways. You might bring home a dozen and enjoy them raw on the half shell as an appetizer, or invite family and friends over for that lowcountry tradition we all enjoy, the oyster roast. Regardless of how you enjoy them, please consider recycling the shells by dropping them off at one of the locations listed below.

The shells are returned to the estuary as living shoreline structure, which allows new oysters to settle and grow on top of them. Oysters serve as habitat for marine life, they restore and protect shorelines from erosion, and are a critical part of our coastal ecosystem.

When dropping off oyster shells, please be sure not to include trash such as napkins or cracker wrappers, and do not leave behind bags or other carrying devices.

Please also do not attempt to recycle the shells yourself by placing them in the water or on the bank oyster shells must first be quarantined and cured before being used to construct reefs and oyster banks.

Beaufort Bin - Beaufort County Public Works

Bluffton Bin - Trask Landing

Hilton Head Bin - Coastal Discovery Museum

Port Royal Bin - Sands Beach Boat Landing

Lemon Island Bin - Edgar Glenn Boat Landing

Hunting Island Bin - Russ Point

St. Helena/Lady's Island Bin - St. Helena Recycling Center

For hours and more information in S.C. call (843) 953-9397 or visit www.saltwaterfishing.sc.gov/oyster.html

• Eastern, or American oysters (Crassostrea virginica) grow in clusters in our coastal region due to the lack of naturally occurring rocks in our creeks and rivers. Oysters need something solid to adhere to so they aren’t carried away by tides while they grow to maturity. Here, juvenile oysters cling to existing oyster beds and are mostly harvested in clusters. Oyster farmers in S.C. and Ga. have developed methods of growing single oysters by providing seed oysters with sheltered environments in the water that allows them to grow without attaching to structure or hard surfaces.

• Oysters are critical to the health and well-being of our coast. Oyster beds, or rakes, prevent shoreline erosion and provide habitat for numerous species to spawn, feed and grow. This nursery is an important part of the food chain. In addition, a single oyster can filter up to 50 gallons of water each day, removing harmful toxins and pollution, controlling phytoplankton, and reducing nitrogen levels in the water. The oysters don’t consume harmful pollutants – they form a mucus around the bad stuff and eject it back into the water where it’s then consumed by other organisms feeding in the oyster beds.

• To harvest wild oysters, look for clusters that have two or three live (unopened) oysters that are each at least three inches long. Use a small hammer to lightly break off the cluster. Gently tap off smaller oysters so they can continue to grow and remove dead or empty shells and leave on the rake. These help the rake continue to grow by adding structure. Oysters are not only great tasting, but great for you! They have a host of vitamins and nutrients, including B12, copper, calcium, iron, manganese, selenium, zinc, as well as protein and amino acids. See our video on Facebook on how to shuck an oyster!

• Oysters grown in different areas will have different flavors. An oyster from one end of a barrier island can taste subtly different from an oyster grown at the other end. Similar to wine grown in different regions tasting different due to soil composition and climate, filter-feeding oysters can take on flavors based on the composition of the water around them. What are your favorite oysters?

Georgia Locations

Brunswick Shell Recycling Center - DNR Campus

Darien Shell Recycling Center - Champney River Boat Ramp

Jekyll Island Shell Recycling Center - Jekyll Recycling Center

Tybee Island Shell Recycling Center - Polk Street

For hours and more information in Ga. call (912) 598-2387 or visit gacoast.uga.edu/education/adult-education/oysterrestoration/

Compiled by Amy Thurman Healthy oysters like these will be a lovely pale color and floating in their own clear liquid. If a raw oyster has an odor or no liquid, don't eat it. Photo by Amy Thurman This common sight of an eroded shoreline and struggling oyster reef can be restored using recycled shells that you contribute.

This article on oyster farming in South Carolina is a compilation of two articles orginally published in very early issues of Southern Tides. It is being reprinted in honor of our first oyster issue.

Article and Photos By Amy Thurman

Iarrived at Lady’s Island Oyster Farm on a breezy and overcast Friday afternoon to meet the owner, Frank Roberts, and learn about oysters. After a hectic week of meetings, ad sales calls, tracking down information, and entirely too much time in front of a computer, it was also an excuse to spend a few hours outside doing something fun. I had no idea I was in for a lot more.

The setting was, in part, familiar: huge live oaks bordering marsh grass, with the occasional piece of driftwood adding texture, a dock running out over the river, gulls swooping and laughing, and the earthy and soothing scent of pluff mud that eases tension in the shoulders better than any massage.

But there were a few distinguishing and less-familiar features as well, such as the cement-block former juke joint that’s being restored and given new life as a seafood shack, and the remnants of pilings from a dock that used to serve rum runners during Prohibition. I love a place with a colorful history, as this adds a bit of swagger to its step. Come to think of it, I enjoy people like that too.

Other distinguishing features were the hatchery shed and nursery station, where Lady’s Island oysters, known as “Single Ladies,” get their start in this world, and where Frank started me in my education of lowcountry oysters.

It all begins with a boy and a girl. Or in this case, a boy and five girls. After determining gender, a single male oyster and five females are isolated in a tub of river water at the appropriate temperature to trigger spawning. This setup begins at the same time oysters naturally spawn in the wild, usually in April, and runs through the summer until water temperatures drop in the fall.

After careful monitoring and critical maintenance of the spawn, called spat, for 19 to 21 days, the larvae reach “setting” age, when they attach to grains of finely ground oyster shell, roughly their same size of approximately 100 microns. To demonstrate, Frank placed a dropperful of larvae in a small dish and we looked at them with a microscope. Round, amber-colored, with a small dark “eye,”

and a valve that resembled a tiny tadpole, this microscopic oyster was attached to a sliver of shell – as I watched, it flexed open, then closed, the movement that will one day open and close its shell as it filters nutrients.

Over the course of about four weeks, the oysters grow to around 1000 microns and are transitioned from hatchery to the nursery station into mesh-bottomed containers called silos. As the oysters grow, they’re moved to silos with increasingly wider mesh. When they’re about the size of a dime, they’re transferred into mesh bags, which are placed inside protective cages and moved to the river.

Safer from predators, such as boring sponges and crabs, than their wild cousins, and without the growth constrictions of having to cluster to survive, the survival rate of farmed oysters is significantly higher than in the wild. One half of one percent of wild oysters survive the larval stage, compared to a full six percent survival rate of farmed oysters. After the oyster larvae set, the survival odds increase. “We only lose about 15% after they set,” Roberts said. That loss can go as high as 90% in the wild. Given that a single oyster can produce over 100 million unfertilized eggs in a single spawning, this equates to significant increases in the oyster population with farming.

As these farmed oysters grow in the river, they’re periodically rotated into bags with larger mesh until they reach the perfect size of three inches, at which point, they’re ready to be delivered to restaurants. Wild oysters take about three years to reach that size, but Roberts and his crew have reduced this time; their farmed oysters reaching the legal 3-inch length in ten months.

Farmed fish and seafood get a lot of bad press in today’s world, largely due to health issues posed by products imported from countries with little or no oversight or regulations in the farming process. And while a lot of that bad press is well-deserved for imports, the same can’t be said of aquaculture in the U.S. In fact,

the benefits of farmed seafood, such as oysters, have positive impacts on the environment, the economy, and individual health.

Although most of these farmed oysters will eventually make their way to someone’s table, the process is still highly beneficial to the environment. Filter feeders, including oysters, clams and mussels, are critical to the health of our coastal waters; a single oyster can filter up to 50 gallons of water per day.

“Shellfish aquaculture operations, such as the farms in South Carolina, can serve to improve water quality by helping to control phytoplankton and remove suspended solids from the water column,” said Dr. Peter Kingsley-Smith, a marine scientist with the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources (SCDNR). “Furthermore, by consuming algae, oysters have been shown to reduce nitrogen levels and may therefore play an important role in addressing eutrophication, or excess nutrients in the water that can lead to unwanted algal blooms.”

But filtering out all this bad gunk doesn’t mean the oyster consumes it or that contaminants are trapped in the shell. Instead, a sort of mucus is formed around the pollutants, which are then ejected and serve as food for other sea life.

Wild oyster rakes and the cages used with oyster farming also provide habitat for smaller marine life and feeding grounds for fish and crabs, offering prime fishing spots for local fisherman. In addition, farmed oysters take pressure off the wild stock, preventing over-harvesting, and allowing wild oyster rakes to continue to grow, thereby adding stability against erosion to water bottoms and shorelines.

This sustainable resource in turn has a positive impact on the economy. In South Carolina and other states practicing aquaculture, oyster sales to restaurants and individual consumers is on the rise, as is the sale of seed oysters to other farmers.

“We’ve increased production 30-40% every year,” said Roberts, “and we’re selling everything we produce.”

But what about the health benefits to humans? Unlike much imported seafood, which is often farmed in polluted ponds and fed a diet with growth and preservative additives, locally farmed oysters have the same diet as their wild cousins, with no additives, and live in their natural habitat. What you get when you open the shell is 100% natural. And you can’t beat ‘em for necessary nutrition. “Eating two oysters gives you all the minerals and nutrients you need for the day,” said Roberts, with a chuckle.

Loaded with Omega 3 fatty acids and zinc, they’re also excellent sources of protein, calcium, iron, and Vitamins B and C. The body absorbs these nutrients at a far higher rate when consumed naturally than when taken as a supplement. Some studies have also shown that eating oysters raises HDLs (good cholesterol) and lowers LDLs (the bad stuff). Consider the oyster nature’s way of giving you

Top: The hatchery shed at Lady's Island Oysters.

Middle: A dish of larval oysters just at the setting stage.

Left: The delicate and nearly translucent bit of white shell around the outside edge of the oyster, called frill, is new growth that in time builds up and hardens as the shell grows.

Opposite

called green shelling. The algae aids in the setting process for new oysters, providing a textured surface to adhere to. Empty shells are also removed from the cluster, which helps the rake continue to grow by providing structure, and means less weight to carry back to the dock.

After gathering a bushel of wild oysters, we waded back to the boat and made our way back to the dock.

Once on land again, Frank and I sat in the shade of live oaks near the hatchery and talked oysters.

There’s a rich history associated with this shellfish. “Some of the first colonists to become wealthy made their money in the oyster industry. In Manhattan in the early 1800s, it wasn’t hot dog carts you saw on the streets of the city,” Frank said. “It was oyster carts.”

The industry continued to thrive until the Industrial Age. At that point, water pollution decimated the oyster harvest in most areas. “Now that the water’s being cleaned up, the industry and the traditions that go with it are making a comeback. Not one hatchery anywhere in the U.S. could fill all of their orders this year.” About 30% of the seed oysters Frank raises are sold to other oyster farmers in North and South Carolina. Demand exceeds supply, which is a healthy position to be in.

“Are you ready to sample some oysters?” Frank asked, as he pulled out a cooler and offered me a cold beer. (Oh yeah, I love my job!) Also in the cooler were several of his own “Single Lady Oysters,” named for the fact that they grow singly rather than in clusters like their wild cousins.

“See this nice pale off-white color?” he asked, opening the first one. “That’s a healthy oyster. And the liquor has a nice sheen to it. If you open an oyster and there’s no liquor in it, don’t eat it. If the liquor can drain out, contaminants can enter the shell.” Although he had two different sauces to compliment the oysters, I was instructed to go plain on the first one so all I would taste was the oyster. I have to confess, it had been a while since I’d had raw oysters and the last time I’d gotten one that was a little less than fresh. I was a bit worried that I might not be able to eat an oyster straight out of the shell again without that memory setting off my gag reflex. Though of course I wasn’t going to admit that to Frank!

But the oyster he handed me smelled clean and fresh, so I tipped it up and slid it into my mouth, straight from the shell.

“You have to chew it,” he said. “Chewing these oysters really brings their sweetness out.” So I chewed, and it was absolutely delicious. The memory of that bad oyster was instantly replaced and my worry vanished.

Next he suggested I try one with a homemade mignonette, a thin translucent sauce made with rice wine vinegar, white wine, diced shallots, lemon, and freshly ground black pepper. I’ve never eaten anything but cocktail sauce on oysters, so wasn’t sure what to expect, but it smelled wonderful and it definitely complimented the oyster even better than cocktail sauce.

We wrapped up the day sipping cold beer and eating cold oysters. I can honestly say they were the best oysters I’ve ever eaten. Many thanks to Frank Roberts for the education, the experience and the oysters!

Frank’s recommended reading: A Geography of Oysters: The Connoisseur’s Guide to Oyster Eating in North America, by Rowan Jacobsen.

Also on our reading list: The Big Oyster: History on the Half Shell by Mark Kurlansky

½ pint rice wine vinegar

½ pint white wine

Minced shallots to taste

A bit of lemon zest

½ lemon, squeezed

Freshly ground black pepper

Salt to taste

Mix all ingredients together (in a mason jar) and refrigerate for one day

When applying Mignonette to oysters, use a cocktail spoon to avoid using too much and overpowering the natural flavor of the oyster.

This article is dedicated to the memory of Brian Cabral, oysterman.

Our deepest sympathy to his wife Julie, and family.

What happens when a couple lowcountry boys get creative? Oystaflage! Camouflage for those who enjoy the coastal lifestyle.

How cool is that?

When brothers Bart and Matt Key set out to design a camo-patterned boat tote bag, they learned that camouflage patterns are licensed and you can’t just pull one off the internet and use it. So they decided to create their own. And what describes the lowcountry better than oysters?

“We knew we wanted to use oysters but couldn’t seem to find the right colors. One morning a buddy dropped us off on an oyster bed at low tide to take some pictures and when he came buzzing back by, the wake washed water up on the oysters, and there it was. The dry, exposed oysters we’d been taking pictures of didn’t work, but once they were wet, there were all the colors I was looking for,” said Bart. With that, Tideline Outfitters was born.

Getting the right photos with the right colors wasn’t the end game, though, it was just the first quarter. “As a total rookie, I thought I could take my 8 x 10 picture to a t-shirt shop and I’d be in business. Wrong! I had to learn about repeat patterns, dye sublimation, micro-polys and more. It took almost two years before I ever had something I could hold in my hand,” Bart says.

“The biggest challenge was learning how this printing and apparel business worked. I’ve been a general contractor for over 25 years. Going from building houses to learning about thread count and the different weight and characteristics of performance apparel was quite a transition!”

When he finally had products to show for his efforts, the next step was getting them in front of the public. OystaFlage products made their debut at Southeastern Wildlife Exposition (SEWE) in Charleston, in 2012.

“I was concerned about how people would react to it when

Above:

Opposite

they first see it, but now that’s what I enjoy the most. Once people get over the ‘Are you kidding me?’ factor, they usually realize it’s a very effective camouflage with an even better story behind it. It seems to bring people back to their roots and those who grew up in and appreciate the coastal lifestyle, heritage and this way of life, love it and wear it proudly.”

Bart has recently partnered with Kevin Joseph, founder and CEO of Empire Oyster, which provides catering, hospitality and consulting nationwide. Bart and Kevin founded Oysters Unlimited, a not-for-profit organization, with the mission to “Protect, preserve and restore oyster habitat … everywhere.” No small task, but both men are aware of the hard work their endeavor will entail and are dedicated to seeing it happen.

“It’s still in the infancy stage as we’re trying to figure out the best path for this non-profit,” Bart said. “But from the beginning I knew the ultimate goal of Tideline Outfitters was to develop a nonprofit platform to encourage an awareness and appreciation of the importance of oysters in the estuarine and marine environment.”

Given the level of dedication Bart has shown to learning and developing OystaFlage, we have no doubt he’ll succeed with Oysters Unlimited, too.

Long- and short-sleeved performance Ts in the patented Oystaflage pattern.If you're looking for a gift for your favorite lowcountry buddy, the half-shell apron, trucker hats, custom Oystaflage Koozies and many other oyster-inspired products can be found at tidelineoutfitters.com.

The creeks and rivers around Charleston were our playgrounds as kids, and my brothers, sister and I spent the majority of our free time exploring wherever our 15foot Whaler could take us. The experiences we shared are now stories we share with our children. (At least some of the stories!)

The lowcountry lifestyle is centered around the water, so what better place to search for styles and designs that would capture the attraction and ruggedness of this unique region.

The goal of Tideline Outfitters was to create unique, durable apparel and provisions that would represent the coastal traditions and lifestyle we all know and love.

To see Tideline Outfitter's full line of products, including apparrel, accessories even vinyl wraps and oyster steamers, visit: www.tidelineoutfitters.com

For more on their oyster habitat restoration project, visit: www.oystersunlimited.org

OystaFlage - For Those Who Enjoy the Coastal Lifestyle

OystaFlage - For Those Who Enjoy the Coastal Lifestyle

On a fine fall morning I arrived at the Shellfish Research Lab on Skidaway Island, to learn more about their project to create an entire Georgia industry from scratch. The lab is part of the University of Georgia Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant. As I spoke with Emily Kenworthy, the public relations coordinator, it quickly became apparent that I have much to learn about oyster farming and mariculture aquaculture in a marine environment.

In the same manner that states and universities send agricultural extension agents into the field to help farmers become more successful and improve their farming practices, so the University of Georgia provides marine extension specialists to help shellfish farmers be more successful at growing and harvesting oysters, clams and other types of seafood. For the past few years, the mission of the Shellfish Lab has been focused on growing single oysters and reviving the once-thriving oyster industry in Georgia. Hatchery specialists produce oyster seed, or baby oysters, that are sold to shellfish farmers in coastal Ga. and S.C. Shellfish farmers can purchase bottom leases – essentially leasing sections of creeks or rivers – to grow their oysters.

While the commercial harvesting of wild oysters in Georgia is relatively modest and is limited to collecting the bivalve mollusks from wild beds, reefs, or rakes, oyster aquaculture could be a much larger industry in the very near future, thanks to the activities going on at Skidaway.

A bill passed earlier this year in the Legislature provides for the sale of permits to farmers via annual bottom leases in one acre increments. Leases will go for $50 per acre and there will be a fee

of one dollar per cage. The legislation came with controversy over the details, which are being worked out by a stakeholder’s advisory group.

Farming oysters is a multi-step process. The first steps take place in the UGA Oyster Hatchery where researchers spawn oysters, creating larvae that eventually grow into single baby oysters. Upwelling water systems provide aerated water to the juveniles which are kept in place with fine-mesh screens.

As the oysters grow they are moved to progressively larger containment equipment and eventually they are either sold to farmers or used for research at the lab, including the use of bottom cages and floating cages to grow the oysters out. The floating cages lay either just under the surface, or when flipped on top of their floats, just over it. Cages must be flipped regularly, allowing the oysters to be exposed, to protect them from becoming habitat for free-swimming wild spat (oyster larvae) searching for a surface on which to attach and grow. Whereas a perfectly formed “single” farm-raised oyster might fetch seventy to ninety cents at market, one that has been colonized by wild spat and turned into a “cluster” will only fetch about a dime. Flipping the cages also prevents other marine growth from taking hold, and keeps the oyster shells clean.

Down at the dock, I met Rob Hein and John Pelli, the aquaculture extension specialists based at the Shellfish Research Lab on the oysterculture project for the benefit of this developing industry. These guys are where the rubber meets the road, so-tospeak, and the farmed oysters, once they are placed in the natural environment, are their babies.

The task that day was to flip the cages at their research sites in the Skidaway River and Wassaw Sound. After they drop me off later, they’ll return to the cages and painstakingly count and measure every oyster in every bag in every cage. They’ll also count and remove oysters that have died – hopefully a small percentage. There are subtle variations in how the oysters are prepared and placed, such as some of the cages situated on the bottom. The

objective is to determine which growing methods yield the best results, and they’re using the scientific data to derive results.

Rob is a native of Athens, Ga., and a graduate of UGA with a degree in ecology. His background includes middle-school teaching, and he confides that while teaching was okay he missed doing research and was glad to get a glowing recommendation from a former colleague which led to a job at the lab. Rob is very knowledgeable and explains as much of oysterculture as I can digest. He explained diploid and triploid oysters in the cages we worked that day. Triploids cannot reproduce, so do not spend energy on creating sperm or eggs for reproduction. He explained that triploids generally grow faster and therefore can go to market sooner and be more profitable. The team wants to learn more about how they do in Georgia waters.

As we ride out the river and I listen to Rob and John, I begin to realize that there’s a whole world of oyster consumption beyond anything I’ve experienced. My oyster eating and knowledge is limited to the typical lowcountry backyard oyster roast. All over America, people go to restaurants and sample oysters from every coast, with each region of origin having its own tastes and characteristics. Rob explained to me that an oyster from a specific region might be described as “a well-balanced combination of sweetness at the start and a buttery soft brine finish.” Who knew oysters could be a component of fine dining? Not me, but I’m excited about the prospect of eating my way to better understanding!

I can imagine tucking into a sampler platter with oysters from east, south, and west. No cracker, no cocktail sauce, just the oyster speaking for itself. Getting hungry yet?

One notable aspect of oyster aficionados is their willingness to spend real money for the objects of their desire. That translates into opportunity for those who are willing to dive in to the business. And that is coming soon. For now, specialists at the lab are learning how to produce oysters with the ideal shape, shell, taste, and texture, and then to pass on that knowledge – and the spat – to replicate the production on a large scale.

John Pelli is a former Union Camp managing engineer who has traveled all over the world. Of the three of us on the boat, he is also the only person who has actually worked in commercial shellfish farming in Georgia, having once operated a clam farm in Wassaw Sound. His background makes him an obvious choice for extending expertise and practical skills to oyster growers working to get their farms up and running. When I asked him if he’s any kin to my friend and boat mechanic Terry Pelli, he laughed and says, “he’s my brother.”

We pulled up to the cages and as Rob and John began to flip them, I could see it was hard work. Our boat had a winch motor and swing arm to provide mechanical assistance, but as Rob pointed out, flipping 500 cages would be tough. If the water’s the right depth you can flip baskets while standing in it, and John is working on other forms of mechanical assistance as part of the project. Even so, like shrimping and crabbing, oyster farming is hard, physical work.

As the legislation to permit oyster farming was being created, there were differences of opinion as to how much of the year should be allocated to harvesting: cooler months only, or all year long. Another point of contention concerned how bottom leases should be distributed: by lottery open to all, or Georgia residents only, or to the highest bidder. While the extension specialists are undoubtedly aware of these issues, they aren’t concerned with them or with the results. Their only goal is to study aquaculture methods that are sustainable, repeatable, and predictable. All Georgians will benefit from their labors, and I am grateful for what they and the rest of the team at the Shellfish Research Lab are doing.

Want to learn more about the work at the Shellfish Research Lab and help support their efforts to grow the industry? You can by attending Oyster Roast for a Reason on Nov. 17 at the UGA Aquarium on Skidaway Island. The event will feature live music and all you can eat Georgia oysters. Details and tickets are available at: gacoast.uga.edu/oysterroast.

Top: Vertical tube incubators for spat production. Center: Vats of oyster larvae being grown in the Shellfish Lab.

Right: John Pelli and Rob Hein hauling oyster cages for inspection.

Created at Antoine's in New Orleans in 1889, the original recipe was never shared or published. Here's our take on this classic.

Start a new tradition and serve them before the big meal on Thanksgiving, or even as game day fare. As always, remember to shop locally!

Two dozen 3-inch oysters, shucked, on half shell

½ cup salted, sweet cream butter

¼ cup diced parsley

¼ cup diced celery leaves

1 tsp diced tarragon

¼ cup finely diced Vidalia onion

1 tsp diced garlic

½ tsp freshly ground black peppercorns

Pinch of cayenne pepper

Salt to taste

1 cup finely grated parmesan cheese

1 cup Italian seasoned bread crumbs

Rock salt

• Melt butter over medium-low heat in small saute pan. Stir in parsley, celery leaves, tarragon, onion, and garlic. Saute until onion

is tender, stirring frequently. Season with black pepper, cayenne and salt, to taste, stir, then remove from heat.

• Lay oysters out in baking dish (or platter) and top each oyster with a spoonful of onion mixture.

• Sprinkle parmesan cheese on top of sauce, then sprinkle with breadcrumbs.

• Place oysters directly on grill rack over smoldering coals (or medium heat on gas grills). Close grill lid and cook five to eight minutes until oyster meat is done.

• Serve oysters in their shells, on a bed of rock salt to keep them level and avoid sauce from spilling.

Note: For a more original New Orleans flavor, add a tablespoon of anise-flavored liquor to the sauce just before removing from heat. The parsley and celery leaves can be substituted with spinach if you prefer.

For cooking demonstrations, samples, and information on purchasing, handling and eating oysters, attend the Ocean to Table workshop on Nov. 6. www.gacoast.uga.edu/events

Frequent contributer Erin Weeks, with the SCDNR, updated this recipe - oyster pies go back at least to the 1800s! Erin declared this, "An oyster dish for people who don't like oysters - the oysters lose their objectionable texture in this pie, and their flavor comes through as a subtle and agreeable brininess.

2 cups shucked oysters (cut in half if large) in their liquid

1 ½ cups shiitake or baby bella mushrooms

1 leek

¾ cup milk

2 eggs

Half stick of butter

Several cups crushed crackers (oyster, Ritz, Townhouse; all good choices)

Freshly ground pepper to taste

Tabasco or hot sauce of choice

9-inch pie pan or small casserole dish

• Preheat oven to 350 degrees.

• Strain liquid from oysters and set liquid aside. Rinse oysters thoroughly to remove any grit.

• Slice and sauté leeks and mushrooms over medium heat in butter, until mushrooms start to brown.

• Mix sauteed leeks and mushrooms with milk, eggs and 1/2 cup of the oyster liquid.

• Grease casserole or pie dish and cover bottom with a layer of crushed crackers.

• Add a layer of oysters, followed by a layer of the liquid mixture.

• Add several pats of butter and sprinkle with pepper.

• Continue to layer crackers, oysters and liquid. If layer appears dry, add a touch more milk.

• Top with crushed crackers and pats of butter.

• Bake at 350 degrees for approximately one hour.

Note: Aside from the oysters, substitutions are possible for many of the ingredients in this recipe.

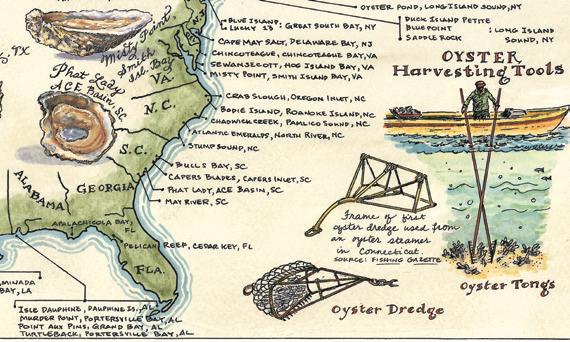

From New World Cartography's Website:

Maps have always been an important part of any culture, whether for conveying information, power, or beauty. Well known maps of the 18th and 19th centuries were etched into copper plates, stamped on paper and color hand applied. These maps were carried by great explorers and adorned the walls of castles. They represented a perfect synthesis of beauty and information.

A map of the description of the major types and locations of oyster cultivation and harvest.

That combination of intellect and aesthetic is rare in maps produced today. Our company, New World Cartography, has taken this old approach of originally designed, hand colored maps and applied it to the 21st century world. Each map expresses the skill of hand drawn lines and text and shows the brilliance of hand applied coloration. All of this is done to a map that was conceived of by our craftsman … an original spatial expression of the world around us.

Map by New World Cartography. Reprinted with permission.

What could possibly be more awesome than a hand drawn map from a cartographer? Only a hand drawn map of oysters!

Southern Tides was thrilled to meet cartographer

Travis Folk, of Green Pond, S.C., earlier this year at the Southeast Wildlife Exposition (SEWE) in February. He was there representing his business, New World Cartography, with maps from all over the southeast, on a variety of themes. After learning of his oyster map, we knew it had to be included in our Oyster Issue.

Travis was nice enough to answer a few questions for us.

Southern Tides: Why hand drawn maps? How did you get started in this?

Travis Folk: I started New World Cartography for several reasons. I’m a PhD wildlife biologist and work in a firm my father started in the 1980s (and this is still my full-time job), managing plantations. Back in the 80s and 90s, all the maps for plantations were hand drawn. This was done when a timber sale was planned, work in the rice fields needed organizing, and most other land management activities that required a map (and spatial measurements). At that time, my father had an old crusty forester (who was also a former Marine) named Henry Sauls who drew the maps and also had an incredible artistic talent. As a result, we have drawers full of hand drawn maps of plantations that also are beautiful. Many of the maps were hung in the plantation homes and Henry would usually do one of the entire plantation and add sketches of wildlife to them as well. Fast forward to 2006 when I came back from graduate school and started to work in the business. I was doing the same types of work (timber sales, rice field work, etc.) as had always been done but was using GIS to develop the maps. These digitally derived maps were accurate and utilitarian but lacked the passion and beauty of Henry's hand drawn maps. (Henry passed away in the late 1990s.)

I started to think several years ago that there must be a way to get my laptop to produce a map that has the look and feel of a hand drawn map. I tried to use my mapping software to do this and I can definitively say it cannot be done. It’s as simple as a straight line segment – you can tell a hand drawn line from a computer derived line instantly. No contest. At that same time I’d become friends with an artist in Charleston named Tony Waters. He too, loves maps but never knew how to create one. I knew how they should look and be designed but have zero artistic talent. With these two components NWC was born. I design and layout all of the maps and Tony and several other artists help those cartographic visions come to life.

Southern Tides: What led to a map about oysters?

Travis Folk: Like most of my maps, it was something I was interested in. Several books had come out about oysters, especially Rowan Jacobsen's The Essential Oyster. I grew up in the lowcountry and had always heard the mantra that our oysters were the best. While I am partial to ours, I also enjoyed trying oysters from all over. And they were pretty good too! I can remember being in an oyster bar in Charleston and just ordering oysters from places I had never heard of but wondered what their

oysters looked like and tasted like. In fact, I pulled my phone out several times to Google different places. So all of these things converged and I decided to make a map that had as many oyster types on it as possible. While I try to be a locavore, I also enjoy the regionalism of food. It was a fun map to put together!

Southern Tides: What an amazing thing to be able to create! Any other fun new maps on the horizon?

Travis Folk: We're currently working on map of southeastern barbecue sauce regions. I have it designed and might have it done in the next several months.

Visit the New World Cartography website to order a copy of The Oysters of North America, any of their other gorgeous creations, or even request a custom map of your property, favorite island or other some other area dear to you. And be sure to let them know you heard about them in Southern Tides! www.NewWorldCartography.com

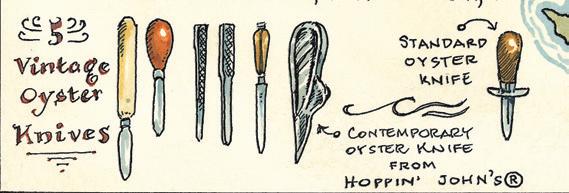

Oyster knives haven't changed much over the years, other than to become more ornate. A good oyster knife and shucking glove is always a great gift idea for the oyster lover. And so is this map!

A Georgia oyster is noticeably absent. Hopefully the oysterfarming industry being developed in Georgia right now will put us on the map - literally!

A Georgia oyster is noticeably absent. Hopefully the oysterfarming industry being developed in Georgia right now will put us on the map - literally!

By Captain Dan Foulds

By Captain Dan Foulds

October means three things are happening in our region. First, the brutal heat of summer is easing into the more user-friendly climate of fall. Second, many of us are watching college football on Saturday afternoons if we aren’t out fishing or hunting. Finally, on many weekend evenings we gather with old friends and new around an oyster roast, engaging in the time-honored lowcountry tradition of shucking and shoving these tasty morsels straight into our mouths.

The term “roast” is something of a misnomer. Roasting involves dry heat, and most of the time we are cooking oysters with wet heat in the form of steam. Whether we steam them in piles covered with hose-soaked burlap on a metal shelf set over a roaring fire, or in a purpose-built propane-fired oyster cooker, or in a boil-pot with an inch or two of water at the bottom and a brick under the basket; the objectives and results are about the same. We don’t want to boil our oysters in water as this would wash out much of the flavor. Rather, we want to cook them gently, in their own juices, and with steam, over several minutes. Steam keeps them from drying out and reduces shrinkage.

As the shells “pop,” or open slightly, thanks to heat and moisture, we dump them in a pile onto serving tables and belly up beside each other. We might stand shoulder to shoulder with a complete stranger, shucking and sharing and laughing at our great good-fortune: the wonder of living a lowcountry life.

Some purists eat them naked. Some dredge them through hot sauce and melted butter. Some like them covering a saltine - the only oyster cracker worth its salt. And then folks like me sandwich them between cracker and cocktail sauce and cram the whole assembly in our mouths at once. It ain’t pretty but it’s fun!

An oyster roast is a great equalizer. It’s a supremely egalitarian thing. You might have a congressional candidate at one shoulder and the lady who cleans houses for a living at the other. The three of you will stand there, enjoy each other’s company, and solve the world’s problems as you harmoniously fill your bellies with this naturally salt-seasoned bounty from the sea. Should you and your tablemates deplete your pile, you will patiently stand and swig your beer or iced sweet tea until another bucket of the steamy bivalves arrive.

Crash! Onto the table they go! “Slide in right here friend!”

Purpose-built tables will have a hole cut in the middle with a shell-bin beneath for easy tossing. The table should be kept cleared for action. Another option is a folding plastic table with a shell-bin on either end. Don’t put anything in the shell-bins but shells, as any trash has to be picked out by hand when they are dumped at one of the myriad shell-recycling options available. On Talahi Island where I live, we dump our shells on the community dock access road to fill the wheel ruts for a level driving surface. They crush under tires and make a fine free roadbed. There are many takers for any leftover

oyster shells, as long as they aren’t mixed with trash. Check with your city or county for recycling options and see the list on page 13 for your state’s living shoreline project recycling center options.

Etiquette? Grab oysters from the pile in the middle of the table, one at a time. Only take what you will eat. It’s okay to shuck for a friend, but don’t expect anyone to shuck for you. Don’t show off your speed-shucking skills at a table populated by casual shuckers, it will make you look inconsiderate. Don’t forget to enjoy the social component of the experience as well as the gastric, in other words, speak with your neighbors between mouthfuls. I mean after all, you do want to be invited back, right?

Invariably, while eating, some bits of oyster will get lodged between your teeth where they hang tenaciously and evade capture. It’s a good idea to have a roll of floss in your pocket for a discreet oysterectomy. It’s also a good idea to bite down gently a time or two on each new arrival to make sure no shell fragments entered your mouth as stowaways. When it's tooth, crown or filling versus shell, the shell will win.

But the number one rule is that there are few rules. Just have fun and be friendly.

As you have hopefully discerned from our oyster issue this month, the future of the oyster industry in our area is bright. From production to consumption, they are already part of our culture, traditions, and history. Thanks to the work of the scientists on Skidaway Island, progress is being made on increasing the harvest right here versus having to buy them shipped in from elsewhere. You can get delicious singles from Beaufort and Bluffton right now and there are other local sources for wild-harvested oysters if you check your local seafood markets. If you’re adventurous and have a fishing license you can even do some harvesting for yourself in selected sections of our waterways. Here’s to oysters everywhere!

Be gentle to man and machine.

"He was a bold man that first ate an oyster."

~ Jonathan Swift (1677 - 1745)

This is one of the most unique and special building complexes in the Savannah area. Unending views of the marsh and water. This 3 BR, 3 BA unit is on the far side and upper level. It is waiting for you to enjoy the balcony deck for dinner or drinks. Once you enter the property you will see water from every angle. The high end finishes just top it off. Welcome to the best view with privacy to boot. Enjoy the 4th Fireworks at Tybee from your private unit or come up one floor for rooftop amenities in the pool or table entertaining alcoves. This unit has water views from all of the common areas, one guest room and the master bedroom. Secure building and parking. Coded entry to the unit. This is the property for the discerning buyer. It has it all. Views, privacy, lock and leave potential, upgrades galore et all. $674,000

This 4 BD, 2.5 BA home is one of the largest in the neighborhood. All of the family is together upstairs with lots of family rooms to boot. Huge bonus room upstairs. Large open floorplan downstairs with separate dining room, living room, sun room and an additional office. Great open kitchen with two counters for eating and a large breakfast room. Directly off this room is the double sized patio. Private backyard. No building behind you. Located on a cul de sac. The master bedroom is oversized with a sitting area. The master shower is huge and has a separate water closet. Directly off the master bath is a huge walk in closet and with access to the laundry room. Lots of amenities. Playground and pool. $274,000

This wonderful 5 BD, 3.5 BA family home is ready for you. From the open floorplan with lots of entertaining areas to the back deck overlooking the tidal lagoon, everyone has a space. This is a true 5 BR home with 3.5 baths. Split floorplan and master is on the first floor along with two other bedrooms. Living Room with FP and builtins and Dining Room welcome you as you enter. The family room and kitchen are open to each other and the back deck. Oversized two car garage is deep enough for storage and cabinets. This community is so perfect for your family. Lots of amenities. Gated community but close to all shopping and schools. Don’t miss the crab trap right out your back door. $495,000

This Spacious 3 BR 2.5 BA home in lake front in Palmetto Cove. Great floor plan with the master suite on the main level and 2 additional bedrooms upstairs. This home features a formal dining room as well as an eat in kitchen, family room, 2 car garage, large pantry and a laundry room. The home also features a screened in porch overlooking the lake. $319,500

This is a very special area and home. Located just off Pooler Parkway with easy access to I-16 and Savannah. A gated community with amenities that just do not stop. Private dinner club, exercise studio, tennis facilities, and a pool entertaining area that far exceeds any expectations. This 4 BR/3.5 BA home is located on one of the wonderful estate lots that is just over an acre. Custom built with two master suites. One upstairs and one down. Perfect for a multi generational family. Four bedrooms and a large bonus room. Multiple living and entertaining areas. There are minumum requirements for the dinner club. Come make this your perfect family home and enjoy all that Westbrook has to offer. $619,000

Build Your Dreams on this Vacant Lot in Established Beaulieu/Montgomery Area! Property Features Gorgeous Oaks and Mature Foliage with Private Well & Septic. Located Near Bethesda, Burnside Island, & Rio Vista, Yet Convenient to Truman Parkway. Offering Desirable Frontage on Ferguson Avenue, The Two Adjacent Lots “0 Lehigh Ave” and “10001 Bethesda” MUST Be Sold Together as One for $125,000. The Property Features Combined Acreage Totaling 1.32 Acres. So Much Potential!! Make Your Appointment Today! $115,000

OMG!! 4BRs, 3BAs. That is all you can say about these views over the marsh and Vernon River. The sunsets alone are breathtaking. This traditional Low Country home is located on 2.8 acres and has views out of every window. Inground pool and screened porch overlooking the view as well. This estate is perfect for the discerning owner with privacy and lots of potential for gardens or a fam ily compound. Burnside Island is a unique island with single family homes and lots of walking, rid ing, etc. Golf cart approved island. Owner may ap ply for membership in the Burnside Island Yacht Club on the Intracoastal Waterway.

Wow!! No lots like this in Parkside. 4 total lots with amazing outdoor space. This charming bungalow will draw you in and make you want to settle in for life. Two bedrooms and bath down and a fantastic master suite and sitting area with bath on second floor. Hardwood floors and contemporary kitchen. There are two outdoor screened areas. Detached single car garage with lots of extra storage. Parkside is such a welcoming community with lots of friendly neighbors. Walk to Daffin Park for the dog park, watching games or enjoy the Banana games and fireworks. Ready for you now. $349,000

This wonderful 2 BD 2.5 BA home was originally the location of a dairy farm. Two buildings for living. One two story with a wonderful master suite upstairs with new bath and large closet. Separate “bunkhouse” has full bath, bedroom, kitchen and living area. They are joined by a cozy courtyard and expansive deck perfect for back yard enthusiasts. Large detached workshop and several outdoor storage buildings. Welcome to Isle of Hope! Walk everywhere. To the marina, to the community pool, along Bluff Drive with views of the Intracoastal Waterway. The community is one the few golf cart approved areas. This special historic home is for the lover of beautiful and unique properties. Perfect for second residence or investment. $369,000 113 Holcomb Street

Living shorelines provide a natural and stable alternative to rip rap and sea walls. Zulu is pleased to offer installation where stabilization and shoreline restoration is needed.

• Assembled with bags of recycled oyster shells

• Stabilizes eroding shorelines or failing bulkheads

• Plantings of native grasses enhance stabilization

• Encourages growth of oysters, which provides water filtration

• Provides habitat for multiple fish and crustacean species

• Increases resistance to flooding