5 minute read

Editor's Note

It was a large ship and so many passengers one could hardly find room. We were all packed together. Father and Edward and August Hacker, who went with us to America, did not suffer seasickness but the rest did. The girls suffered greatly of seasickness. Mother could not stand it in the mid-deck and forced her way to where she and father could be on deck, and this was good for her. The sea air relieved her asthmatic condition and heart pounding, and after coming to America had no further breathing trouble.

Hour after hour we stood on deck and watched flying dolphins, or we looked into the far distance hopefully to see another ship.

Advertisement

For two days we had a severe storm. Everything not properly secured and fastened, flew from one side to the other, especially the tin utensils of passengers, which create a terrible noise. One could hardly understand a word spoken to us. The waves broke over the deck. No one could be on deck during the storm. Even after the storm subsided, one could see the huge waves, which were “house high.” One moment we were in a deep valley, then on the crest of the wave. All description fails, one must personally experience this.

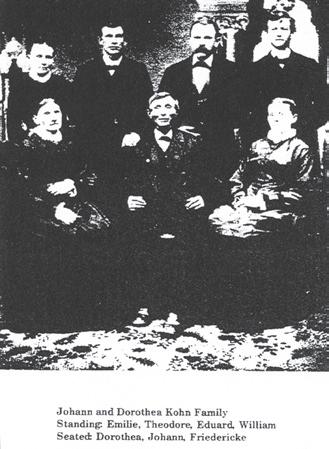

Excerpt from the memoir of Theodore Friedrich Christian Kohn, my second great-grandfather, describing his passage aboard a ship to America. The family emigrated in 1871, when Theodore was just 11.

I’ve recently done a lot of research on my family history and have managed to trace both maternal and paternal lines back multiple generations. Two lines of my family came to the American Colonies before the Revolution, and in fact my 5th great-grandfather, Roger Thompson Clements, fought in that war.

When you go back a couple hundred years, records are scarce. Census records prior to the Civil War didn’t list women or children by name, everything was handwritten, and it seems good penmanship wasn’t a requirement when hiring census-takers. Church records can be a wealth of information, except in the case of my 5th great-grandfather Gabriel Clark, who was expelled from the Quakers because he married a woman outside of the community. If she’d become a Quaker he could have returned to the “Meeting” but he then went on to join a militia group, around the time of the American Revolution, and that’s less forgivable. Regardless, that was the end of his (my) line in Quaker records.

Unless I can find journals, letters, other memoirs or family bibles that were passed down their lives will remain a mystery. This saddens me. When a fourth cousin on my mother’s side, who’s also researching our family, offered me a scanned copy of Theodore’s memoir describing his childhood in Germany and his journey to the U.S., I felt like I’d struck gold!

The memoir goes on to his arrival in New York. A case of smallpox was discovered aboard so they were quarantined for three days and all passengers were vaccinated. He writes of landing:

We came to the old “Castle Garden” where annually, thousands of immigrants land. Later, Castle Garden was razed, and Ellis Island became the landing port. We spent one night in Castle Garden lying on the floor or on benches until we boarded a train which took us westward.

“Westward” was to Chicago, where Theodore’s uncle had settled three years prior and was waiting for them to arrive. He writes:

We arrived in Chicago either on October 23 or 27th. We saw a picture of devastation. Everything burnt, turned to charcoal, or still smouldering. All around Union Depot on Canal Street, board shelters had been erected to serve as hotels, restaurants and saloons. Because Uncle did not meet us at the depot, we, too, had to stay in such a hotel.

The Great Chicago Fire was October 8 – 10, in 1871. To read a first-hand account of the aftermath of a historically significant event, written by my great-great-grandfather, brought an amazing sense of connection not only to him, but to the past, bringing it to life like no history book possibly could.

This research has made me conscious of what my descendants will have on hand to learn about the lives of myself, my siblings, and our children. Will we just be recorded names and numbers on census reports?

Grandfather Theodore started his memoir with this note to his children:

As to your request that I should write in detail about [my family], also about my own youth, I should first of all declare to you that I see no real purpose in it, nor do I have the desire nor the time for it. However, since you have the right for such a request, I cannot deny, and I cannot doubt that you would like to know more about our family than you have heard before.

While he certainly made it clear he saw no point in writing all that history down, he couldn’t possibly have foreseen the pleasure I took in reading it.

I would encourage each of you to consider doing something similar for your descendants. Our lives may not seem of great significance in the grand scheme of things but every life is interesting – and even more so to those who have some connection to us.

Reading about Theodore tending sheep as a small boy, learning English, working in a door factory at the age of 12, later going through Seminary and becoming a minister, and even later, mentioning the birth of my great-grandmother Dora, all those things fascinated me. Your stories of meeting your spouse, what you do for a living, taking your kid fishing for the first time, vacations, living through hurricanes – someday, a distant relative may read it and feel a stronger connection to their family, to their roots, and to history, than you can now imagine.

So write your story. It doesn’t have to be long. Theodore’s was less than 40 pages – but the echoes through time are huge!

See you out there!

Amy Thurman Editor in Chief amy@southerntidesmagazine.com