9 minute read

Exploring Sapelo - Part I

Advertisement

Exploring Sapelo Part I, The North End

Article and Photos By Amy Thurman

Although my two previous visits to Sapelo (in 2009 and September of this year) were spent on the South end of the island and mostly touched on modern history (under owners Howard Coffin and R.J. Reynolds), subsequent reading and research, as well as talking with island residents and guides, has led me to the understanding that the true life blood of Sapelo runs much deeper than mansions and millionaire industrialists. Not to minimize their contributions, but the heart of the place beats in her people and her wildness. That’s the Sapelo I’m falling in love with and that’s the Sapelo I want to write about. But to get to that inner beauty, you first have to pick your way across the sandy beaches, through the maritime forests and swampy lowlands, going back in time then forward to the present to gain a thorough understanding of this wild and unique place. To do that, I would have to go back and visit Sapelo again.

On a perfect fall day, I met my guide (and friend) Aimee Gaddis at the ferry dock and we rode over to Sapelo on the upper deck, protected from the chill morning breeze by the cabin where Captain Mike Lewis manned the helm on the 30-minute ride. Our plan for the day was to explore the historical spots and geographical features of the uninhabited "north end," that hadn't been covered on my two previous visits.

We reached the island, loaded our gear into Aimee’s Jeep, and took off the doors – the temperature was perfect enough for humans but not quite right for gnats, a rare combination in coastal Georgia. We left Marsh Landing and headed north along West Perimeter Road, an unpaved track that winds up the western side of the island.

There are a number of tabby ruins on Sapelo and the first we encountered was at Hanging Bull. Like several locations on Sapelo, the origin of the name is unclear. One legend claims that during the Hurricane of 1898, a large bull was found in a tree after the storm. Another, dating back even earlier, is that an African American was hanged there during the plantation era. We’ll look more closely at the history of Hanging Bull in a future segment.

Venturing on north, we passed the turnoff to the Moses Hammock hunt camp, a sort of base point for hunters utilizing the RJ Reynolds Wildlife Management Area (WMA) that covers 9,000 acres on the north end.

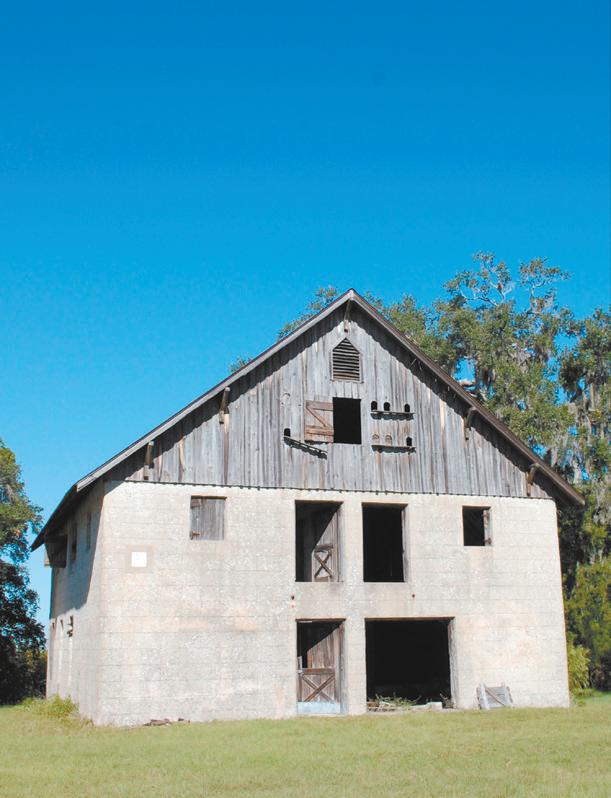

Our first exploration of the day was at Chocolate Plantation. We turned off the track into an open field with tabby ruins to either side and a restored tabby barn perched on a bluff overlooking the Mud River and Sapelo Sound.

Chocolate is thought to have originally been named after a Guale Indian settlement, Chucalat, then later named Chocolate by a group of Frenchmen fleeing the Revolution who purchased the property in 1789. The plantation changed hands several times until Thomas Spaulding, who owned most of the south end of the island, purchased it in 1843. From that point, his son Randolph oversaw cotton production on the land. Through most of its history, until the Civil War, the plantation lands were used to grow sea island cotton and manned by slaves. The property is now part of the land owned by the DNR.

After Chocolate, we continued north to High Point, the furthest point north, where ships once docked to take on cotton and other products from the north end plantations. Ruins of a tabby house and a narrow section of shell beach are all that remain of what was once a busy landing. We sat on the beach and ate

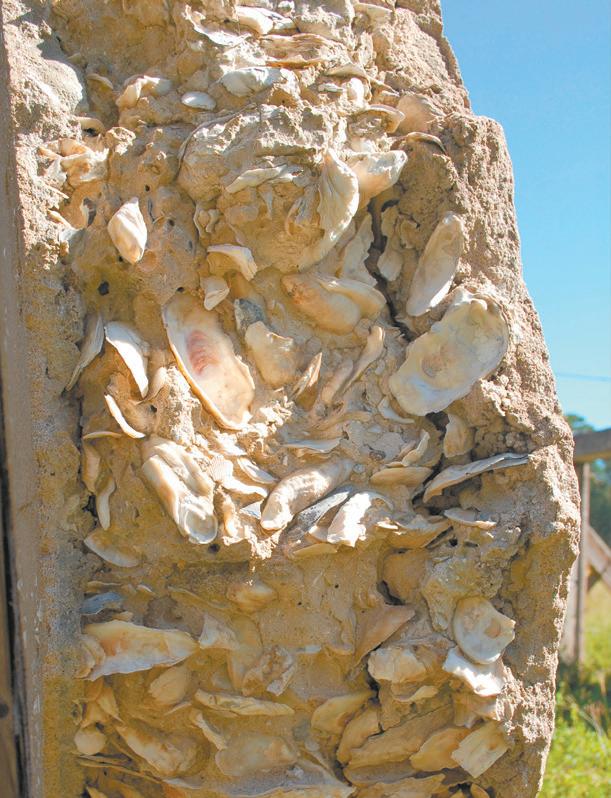

(Opposite page) Top Left: Live oaks create nature's cathedral in the maritime forest on the north end of Sapelo. Top Right: The main house on Chocolate Plantation burned in 1853 and was never rebuilt. All that remains are sections of the original tabby, such as this fireplace. Bottom Left: A close up of Spaulding's tabby compound, equal parts oyster shells, lime and sand. Bottom Right: A "newer" barn, built by Charles Rogers in 1831 and restored by Howard Coffin in the 1920s. (This page) Top: The tabby ruins at High Point. Bottom: The shell rake at High Point, once a busy boat landing for plantation goods.

Above: To demonstrate the scale of the shell ring just south of High Point on the northwestern side of the island, Aimee stands in the middle of an excavated section. Inset: A closeup of the shells that make up the ring.

the lunches we’d packed as we talked about the island and life in general. It’s a peaceful spot, with only the quiet sound of small waves rushing through marsh grass and the occasional cry of a bird, while dolphins broke the surface of the river in front of us. Daily life, with its noise, electronic devices, schedules, and demands seemed far away and you could almost feel the stress of it drain away through your limbs, sitting there with only nature surrounding you. I didn’t want to leave that spot and found myself fantasizing about building a small cabin on the bluff, miles from other humans, and living out my life there unbothered by the modern world.

There was more to see though, and too soon we returned to the Jeep and continued on our way. After a detour around Duck Pond we stopped at the site of a large shell ring. Picking our way along a faint trail, we walked over the rise of one side of the ring, crossed the wide shallow center, then came to a section that had been excavated. The section (where Aimee stands in the photo above) was initially cut away by a Reynolds' employee, without permission, sometime prior to September of 1949, when archaeologist Antonio J. Waring, a guest of Reynolds, studied that ring and two others on the island. Based on pottery finds, Waring determined that the circles, as he referred to them, were from the Late Archaic period, 3000-5000 years ago. To think of what life might have been like when the first layers of shells were laid, in comparison to life today, the contrast is almost beyond words. But in this dense forest, so cut off from the outside world, it’s easy to imagine that not a great deal has changed at all.

From there we moved on to Bourbon Field, then King Savannah, both fields that were previously cultivated for crops, and around which small communities of Freedmen once lived, before finally reaching Raccoon Bluff.

In the years following the Civil War, Raccoon Bluff was, for a time, the largest Geechee community on the island. In 1871, freedmen William Hillery, John Grovner and Billaly Bell formed a partnership called William Hillery and Company and purchased nearly 1,000 acres around Raccoon Bluff. Each partner kept 111 acres, while the remaining 666 acres were divided into 20 lots of about 33 acres each and sold or leased to other freedmen. The community included a general store, a school, and the First African Baptist Church, which still stands today and is used for special services.

Aside from the church, there’s little indication that a thriving community once stood in the open space overlooking the bluff. Most of the residents were relocated to Hogg Hammock during the Reynolds years, through “land swaps” that don’t appear to have been entirely scrupulous.

As we meandered along the tracks that crisscross the island that day, I noticed areas that reminded me of other barrier islands. One spot of mature maritime forest, with its tall canopy of Southern magnolia and live oak, and intermittent sawtooth palmettos

reminded me of the interior of Ossabaw Island, while the eastern side with wind-shaped myrtle opening to dunes reminded me of the eastern edges of Cumberland. But while the barrier islands are similar in terrain, flora and fauna, each is unique and magical in its own right.

The Coffin and Reynolds influences on Sapelo Island are widely published and the focus of public tours, and each did contribute in large and small ways to the Sapelo of today, yet it was good to get away to the wilder side and experience the natural beauty of the island. In the next two installments we’ll look at the scientific research that much of the southern part of the island is dedicated to, then finally, the lives and history of the Geechee people who’ve made Sapelo home for more than two centuries.

Many thanks to Aimee Gaddis for her time, knowledge, and research materials.

For private tours of Sapelo, contact: Aimee Gaddis (912) 230-3218 or J.R. Grovner (912) 506-6463

Right: The First African Baptist Church at Raccoon Bluff, built in 1899. The church is still maintained and used for special services, though the congregation now attends regular services at the new F.A.B. Church in Hogg Hammock.

Below: The view from where Raccoon Bluff once thrived, overlooking Blackbeard Creek.

Family Owned and Operated Since 1977

Parts and Service - Boats - Trailers - Outboards Accessories - Boat Gear - Rods - Reels - Tackle Serving all of coastal and south Georgia for your shing and boating needs! 1807 Old Reynolds Street • Waycross, GA • (912) 285•8115 • sales@satillamarine.com

• Apps, burgers & fresh local seafood • Full bar • Indoor & outdoor dining • Live music on weekends • Open seven days

Come by boat! 912-319-2174

JEKYLL HARBOR MARINA

• Dockage and Dry Storage • Gas/Diesel • Wifi, Cable TV • Courtesy bicycles • Pool • Pump-out • Ship’s Store 912-635-3137 inquiry@jekyllharbor.com www.jekyllharbor.com

ZACHRY'S - Providing fresh seafood in Glynn County for over 35 years!