6 minute read

a space the eye cannot see

Even during its heyday in the late 19th century, the penny farthing was known as a notorious killer. There’s a reason that the modern diamond-framed bike was marketed as the ‘safety bicycle’ when it was first introduced: the penny broke necks and impaled people on iron railings. ‘Wheelmen’, as they were known, were the daredevils of their day, akin to today’s freerunners and skateboarders.

Braking is especially inadvisable on a penny, as the rider sits directly over the bicycle’s balance point. As the front wheel slows, the lack of counter-weight from the rear means the rider simply rotates over this fulcrum and does a ‘header’ straight into the ground. As the legs are trapped under the handlebars, there’s fantastic scope for injury. “I’ve broken my wrist four times, my elbows five; my collarbone and my leg,” Summerfield says, “but they’re great bikes.” He did all this while racing his penny against other enthusiasts...

His preferred method of dealing with errant pedestrians and stray dogs is simply to ride them down; it apparently does less damage. Bumps and potholes are equally dangerous, necessitating much dismounting and pushing. Imagine taking such a machine through the high mountain passes of Tibet and the jungles of Cambodia. Thomas Stevens’ account of his circumnavigation (1884-87) is littered with headers, collisions and stretches where he had to get off and push. It’s a wonder either of them made it down the garden path, let alone around the world.

So why on earth attempt long distance touring on such an impractical machine?

For all its danger, the penny farthing has a certain purity of essence that many people find irresistible. It’s the original fixie. There are no gears. There isn’t even a chain. There is nothing to come between the rider and their direct connection to the road. The rider is literally, ‘riding a wheel’. It’s a little like using a quill and home-made iron-gall ink to write a letter. It is simple, elegant, and instead of relying on over-complicated technology to work, it relies on skill. And more than a little bloody-mindedness. Equipping yourself with a top-of-the-range expedition bike can cost thousands of pounds. They can have hub gears, suspension, computers, dynamos to power your laptop and a whole host of other ‘essentials’. Summerfield went to the opposite extreme and built the simplest of bicycles; and in so doing, proved that guts, determination and a sense of humour are far more important to a round-the-world tour than the latest gizmo.

To cycle around the world takes a certain spirit of adventure and a large degree of fortitude. To do it on a self-built penny farthing takes a certain type of brilliant madness. Overused perhaps, but the phrase, ‘mad dogs and Englishmen’ comes to mind after talking to Joff Summerfield. Well, long may mad dogs and Englishmen venture forth in the noonday sun. The world would be far less fun without them.

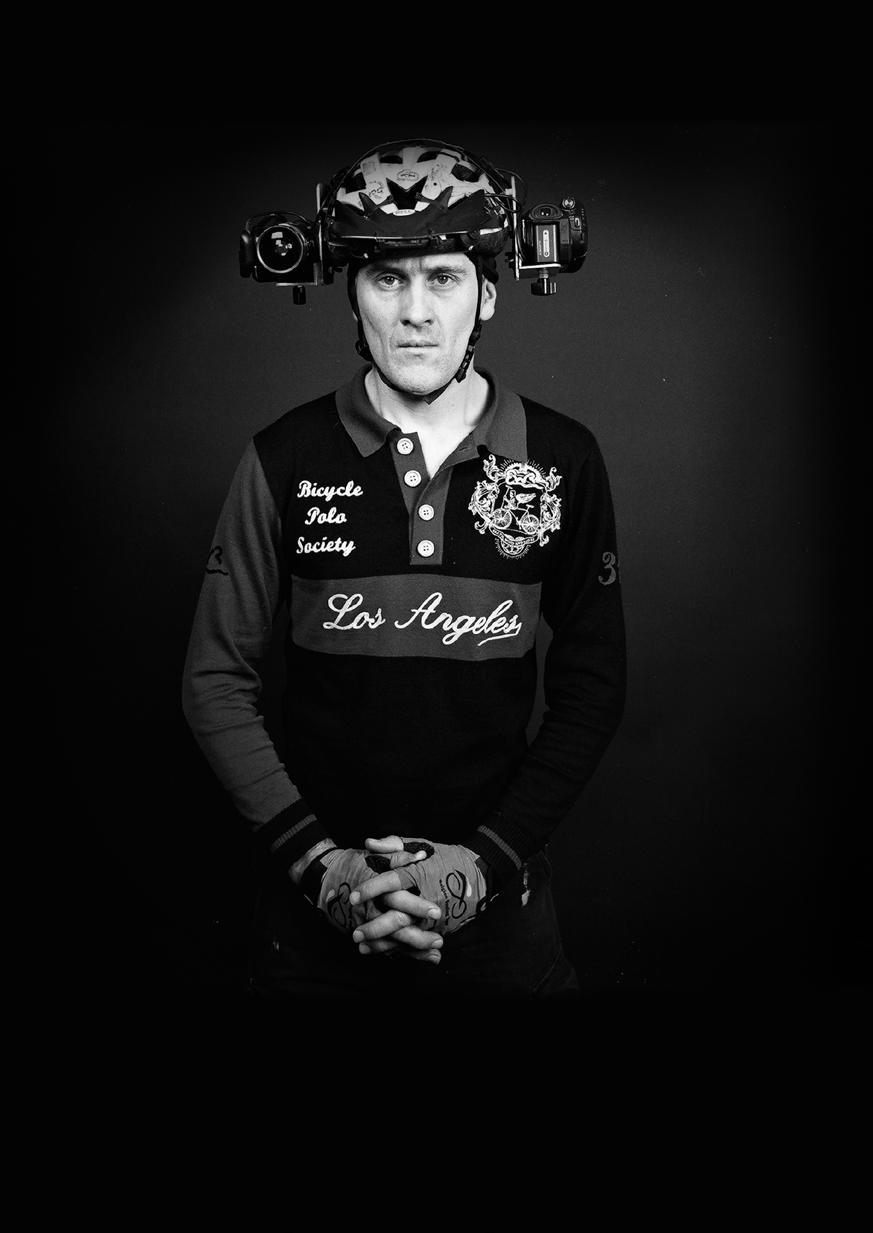

Lucas Brunelle grew up in sleepy Martha’s Vineyard, USA, enjoying “the kind of childhood that produces psychopaths and career criminals,” riding BMX and getting into trouble. He slid in and out of jail and reform school. Returning home after a spell of detention at 16, he founded his own landscaping business and used the proceeds to buy his first road bike from Cycle Works bike shop. “I hung out at the bike shop on rainy days and ran into a couple of racers who invited me to come with them to the Plymouth Rock Criterium. Seeing this race changed everything for me – the speeds, corners, tactics, aggression and rain all added up to my destiny.”

He started to train, and race, and win. Had sponsorship for a while, but his troublesome side brought him down again – his coach Frank Jennings was busted for coke dealing and Lucas ended up with a two-year suspended sentence for “18 felonies plus numerous other serious offences” including burglary and dangerous driving.

He did his time, pulled himself together, went to college, got a job on Wall Street and then set up an IT business, all the while racing and winning. But Lucas no longer got the same buzz out of riding. “It was like the passion was gone. I did well by taking risks and being aggressive. I often rode tight courses like I was on a BMX bike and dropped riders that were much faster than I was – but for what? Amateur racing is filled with catty dickbag riders who think they’re better than you even if you win the fucking race. I was stuck racing Cat 2, trying to decide what to do. I kept couriering and fixing people’s computers. I went on Critical Mass rides for comic relief and it was in 2001 that I met my friend John McLean, who sported a shoulder camera. Bikes had helped me get out of a self destructive cycle, but it wasn’t until I saw his footage that I finally understood my calling in life.” That calling has proved to be the development of a unique and frankly terrifying brand of cycle cinematography. He films alleycat races from right in the quickest thick of the action, keeping level with the riders as they hurtle through the busiest cities in the world.

For those that don’t know, alleycat races involve riding at breakneck speed through the traffic, battling to be first to complete a series of checkpoints on a wild-goose chase across the city. There are no fixed routes and few rules. Usually the only rule strictly adhered to is that bikes must have no gears and no brakes. The only way these riders can slow or stop themselves is by locking the fixedgear rear wheel into a skid.

The checkpoint locations are usually issued to riders on a manifest at the start of the race. To add an element of chaos to the proceedings, manifests are often thrown into the air. The riders’ bikes may be strewn at random around them; the first thing to do after you’ve fought for a manifest is to find your bike. Then you’re off, using your wits and your legs to get round the checkpoints fastest. With no fixed route, knowledge of the streets is a big advantage - but following the rider in front offers no guarantee of success.

Imagine you’re in New York city – though it could be London or Berlin or Tokyo or anywhere - you’re riding at lung-burst pace, absolutely flat out. Your brakeless bike sways beneath you in time to your furious cadence. Someone leans down and grabs the wheel arch of a passing cab, enjoying a free ride for a few blocks. Your competitors whoop and holler as they swerve and dart between the tight-packed traffic.