21 minute read

Introduction

from Shifting Horizons

Introduction: Shifting Horizons – a Line and Its Movement in Art, History, and Philosophy

Lucas Burkart and Beate Fricke

Advertisement

What happens when horizons shift? More specifically, what occurs when that line, which in everyday experience appears so consistent and omnipresent, reveals itself to be contingent? And if the horizon line is mutable, what does that imply about the systems of knowledge, order, and faith that the seemingly immutable horizon appears to neatly delimit and order? These are the questions the following volume of essays addresses, offering perspectives from multiple historical periods and disciplines that tackle instances in literature, history, and art in which shifts in conceptualizing the horizon have made themselves manifest. These shifts, as the contributions here point out, propose models for re-thinking the horizon’s boundaries as mobile instead of static. The horizon, as Albrecht Koschorke has observed, is many qualities: it appears as a motif, a symbol, a locus, and a metaphor.1 Most of all, the horizon is a figure of thought (Denkfigur) that serves as a means of organizing perception and information.2 Fixing the horizon thus means delimiting parameters (visual, epistemological, experiential) that aid in establishing a framework for understanding the world and the place of humans within it. Shifting the horizon, on the other hand, means rethinking the fixity of these limits; it means taking a step over to the other side in order to acknowledge a point of view that may well be obscure or elusive, but which is nonetheless present if one conceives of knowledge and experience as multivalent and situated.3 To make these observations more concrete, we propose to introduce this volume by taking a look at a particular example of a moment in which we can observe the horizon shifting.4 In an illuminated twelfth-century British manuscript we encounter a curious image (Fig. 1). At first glance, it seems a rather unusual choice for an examination of the horizon, for in this image seems to be no horizon at first glance. Looking closer we begin to imagine, however, that it does exist, running somewhere along the diagonal boundary where green and blue waves meet in the image’s center.

1 Koschorke (1990). 2 For the terms Denkfigur and Denkraum in Aby Warburg’s Oeuvre see Treml/Flach/Schneider (2014). 3 On «situated» knowledge see e. g., Harraway (1983; 1989). 4 Alexander (1970), 141 n. 2; Ayers (1973), 127, Fig. 4.17; Baker (1978); Brown (2003), 209; Stein-Keks (2011).

10 Lucas Burkart and Beate Fricke

Fig. 1: British Library, Yates Thompson MS 26, fol. 74v. Announcement of Cuthbert’s death, last quarter, 12th century.

Introduction 11

What can be perceived in this illumination is the moment of a transmission of information. On the upper (green) half of the illumination, we see Inner Farne island off the English coast, where St. Cuthbert built a hermitage and died after a short illness in 687 AD. Two monks signal this death by flashing torches. These lights broadcast the event of Cuthbert’s death to a monk on another shore (in the lower half of the picture), a member of the monastery at Lindisfarne, another tidal island off Northumberland. The latter receives the message and starts to grieve. The emphasis given in this twelfth-century manuscript illumination to finding a pictorial solution for (not) depicting the horizon is striking and surprisingly complex. For the image showing the two monks on opposite shores, must also communicate that the monks cannot see each other. Or rather, that their visual access to one another is partial. For the perspective we have as beholders is not the same the illumination’s protagonists are restricted to. The artist must convey, in one image, that the monks are beyond each other’s immediate horizon, but that they can nonetheless transmit information to one another through the light of their torches. The two monks on the islands, with their specific flora and fauna, are too far apart to see or hear each other; they are beyond the horizontal line demarcating the limits of the visible and audible world, yet the monk on the rocks in the lower left half of the illumination can still receive and understand the message of Cuthbert’s passing. The monk receiving the news of Cuthbert’s death is depicted a second time in the image. With his hands raised in sadness he walks towards his monastery, Lindisfarne. We can see it with its door open revealing an oil-lamp illuminating the darkness inside. The open door and the light indicate a passage inward (and beyond) the monastery itself. The notion of movement or transgression that undergirds Cuthbert’s passage (from life to death) thus finds an echo in the action shown in the image: from the physical world of the island into an illuminated interior, metaphorically beyond even the monastery’s threshold. Cuthbert passes beyond the horizon of the terrestrial here and now, just as the message conveying this movement traverses the perceptual horizon that divides one island from the other. The horizons demarcating the thresholds of life, visibility, knowledge – and last but not least of time – conflate into a single picture. For the beholder of the manuscript, the horizon as a threshold between the visible and invisible lies at the core of this illumination, although it is not frankly depicted: it remains hidden and subject to our imagination. By understanding the demarcation of invisibility and visibility that is put into play in this illuminated page, we also understand the embedded meaning of this picture; the soul of Saint Cuthbert has left the terrestrial world and has ascended to heaven. We, therefore, observe a kind of doubling, since the message that one monk communicates to another – across a horizon – mirrors the passage of Cuthbert’s soul across the demarcation between earth and sky. The horizon referred to but not depicted as a line unfolds its relevance and meaning by asking the observer to imagine multiple interconnected spaces: 1) the horizon between the islands, 2) the death of the saint and the voyage of his soul from life in our world towards eternal life in heaven and, hence, the horizon between earth and heaven.

12 Lucas Burkart and Beate Fricke

Perhaps it should come as no surprise that at the time the illumination was produced – in the second half of the twelfth century – philosophers were trying to define the location of the soul within what was then known as the «order of causes». With the «order of causes» philosophers described an all-encompassing order explaining all causes and their effects, differentiating between higher and lower causes. The soul posed a particularly intriguing question in relation to questions of causality because of the ambiguity of the soul’s origin, location, and afterlife as well as its role within the causal order, e. g., in the process of the generation of human life. The very notion of an order of causes had filtered into the west across an apparent cultural horizon; it arrived via the so-called Liber de causis, an Arabic textual excerpt, which was almost a revision of Christian creation theology attributed to Proclos.5 This text was translated into Latin by Gerhard of Cremona (1114–1187) and had a significant impact upon Western medieval philosophy, for instance on the writings of Albertus Magnus (1193?–1280), Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), and Giles of Rome (1243–1316), to name just a few (see the contribution by Andreas Lammer in this volume). According to the Liber de causis, a person’s soul was located «below» (inferius) the eternal world and «above» (supra) time (quoniam est in horizonte aeternitatis inferius et supra tempus) whereas the body was decidedly terrestrial.6 Humankind was divided in two by the horizon which marked the limits of earthly experience and that which lay beyond. At the same time the illumination was made the philosopher and poet Alain de Lille (1125/30–1203) referred to ideas articulated in the Liber de causis in his De fide catholica contra haereticos in which we can observe how the term horizon steps out of the confines of the neoplatonic tenets that until then had dominated western medieval theological-philosophical discourse.7 The knowledge of ancient philosophy in the medieval period was constrained to a rather limited body of texts. Boethius (–524) and John Scotus Eriugena (–877) were the most influential commentators on Platonic thought and their works contributed greatly to the spread of neoplatonism. In the twelfth century, however, the works of Aristotle (–322 BC) and new works by Plato (428/7–348/7 BC) (e. g., second half of Timaios), were translated into Latin, just as Arabic texts (including translations of Antique texts) were filtering into European philosophical discourse. In his phrase «in horizonte aeternitatis, et ante tempus» de Lille links the term horizon exclusively to the human soul and interprets aeternitas as perpetuitas, or temporal perpetuity.8 The human soul has a beginning but will not have an end (etsi habuerit principium, non habebit finem), he writes, unlike the body which is finite, defined by

5 Anon. (2003), XV–XVI. 6 Ibid., 60 and 119, n. 1. 7 Alanus de Insulis, De fide catholica contra haereticos I, 30. MPL 210, 332; Baeumker (1894), 418 f. 8 Pattin (1966), 138, 165. Vincent Guagliardo points out: «The Arabic is considerably clearer for this proposition: ‹Every destructible and non-perpetuable substance either is composite or is present in something else, because the substance is either dissoluble into the things from which it is, such that it is composite, or it needs a substrate for its stability and subsistence, such that when it sep-

Introduction 13

a horizon designated as earthly. On earth, within the constraints of a visible horizon, the body lives and dies, whereas the soul inhabits a realm whose horizons are unlimited – or perhaps limited only by their contrast to the terrestrial boundaries of life and death. While the mental crossing of horizons, and the creation and circumscription of imagined territories in poetic and narrative texts have been well studied, the effect of changing and shifting horizons in such texts has remained a blind spot.9 When we contextualize an image like the Cuthbert illumination within shifts in philosophical ideas about the horizon, however, we are encouraged to consider how new forms of representation of the horizon emerged to articulate expanding epistemological perspectives. This brief excursus into illuminations and Denkfiguren of the twelfth century demonstrates that the figure of the horizon itself is subject to historical change.10 Depending on location, era, knowledge, and culture, the horizon line is variably and contingently delineated and defined, open to new meanings and configurations. In this sense, the horizon appears not as a constant astronomical or cartographic fixture but as something subject to continuous movements that shift the relationship(s) between the visible world and imaginary realities in incessantly (re)calibrated new ways. New geographical regions – both earthly and imaginary – open up to discovery as new thought experiments and epistemologies extend knowledge into a hitherto invisible or yet unknown world. In this context, new constellations of networks re-configure lived experience based on shifts in thinking the horizon in every age, every epoch. The line of the horizon as a reference point is, however, a key and remarkably consistent element in the history of art, of philosophy, and of history. It is, therefore, often considered a category of static and consistent permanence. It serves as an enduring reference point one can organize and delimit information with: this happens here, that happens elsewhere.11 But as we have suggested, once changed or set in motion, horizons redefine the limits of description, imagination, and interpretation in poetry, literature, theatre, and film.12 Furthermore, the expansion of the horizon defining the known world in ancient, medieval, early modern and modern world changed the order and balance of citizens and imperial structures as well as constitutive elements in descriptions of the (kn)own and the exploration of the (other)world, beyond already charted territories.13 Thinking beyond the threshold, the limit, of the horizon depends, therefore, on trespassing the overar-

arates itself from its substrate, it corrupts and is destroyed. So if the substance is not composite and present [in something else, but] is simple and per se, then it is perpetual and altogether indestructible and indissoluable.›» Guagliardo/Hess/Taylor (1996), 146. 9 Glauch et al. (2011); Hoffmann/Wolf (2012), especially Ingrid Baumgärtner, «Erzählungen kartieren: Jerusalem in mittelalterlichen Kartenräumen», 231–262. 10 Hinske/Engfer/Janssen/Scherner (1974). 11 Koschorke (1990), 49. 12 E. g., in Homer’s Illiad, Book 3, lines 121–244, Auerbach (1938); Koschorke (1990); Siegert (2015); Iser (1983), 547–557; Hawthorne (1994). 13 Reichert (2014); Decker et al. (2009); Pabst (2004); Simek (1992); Obrist (2004); Müller (2008); Canny/ Morgan (2012); Burghartz (2011).

14 Lucas Burkart and Beate Fricke

ching order of an imagined system implied to be constant, consistent, and knowable because it is bounded by the horizon’s line. So, what exactly happens when this line moves, tilts, changes or disappears? How do different cultures and periods react to such an experience of radical change? Do they reorganize or process what previously was considered to have been of constitutive importance? The contributions to this volume address the consequence of these horizon «shifts» and their impact upon the redefinition and reconstitution of the inner structure of works of art and literature, manifestations of the perception of the world and cognition of its (changing) systems, something hinted at by the illumination described above. Reflecting, digesting, or anticipating such changes, shifting horizons have redefined how we think about the organization, meaning, and perception of works of visual art as well as literature, architecture, and urbanism. In the history of painting, for example, the dominant Eurocentric narrative of the so-called rise of perspective, linked to a more «naturalistic» mode of representation aligned with new forms of optical science and the observation of nature since Giotto (–1337) has been repeatedly questioned, although the horizon itself has curiously played a remarkably small role in those revisions.14 In literature, changing horizons impact key elements – such as teichoschopy, i. e., when invisible scenarios and events are described by one of the actors, persons or the narrator – or what the influential German literary scholar Hans Robert Jauss termed the «Erwartungshorizont» (horizon of expectation). Like Jauss, the historian Reinhart Koselleck also insisted on the importance of the horizon as an ordering principle, though Koselleck’s interest was specifically linked to the horizon’s relationship with temporality. For him, the concept of the horizon is one of two poles that societies use in order to locate themselves in the present: between past and present. This present, he argued, determined itself as a negotiation between experience in the world (Erfahrungsraum) and a horizon of expectations, an Erwartungshorizont, à la Jauss that has yet to be experienced, but is nonetheless projected. Whether one wants to accept Koselleck’s argument that a fundamental change in the experience of temporality occurred during the eighteenth century (the transitional period, for him, between pre-modernity and modernity), his observations about the horizon remain important: thinking about the horizon means not only thinking spatially, but temporally – as we have already observed in the case of St. Cuthbert.15 Aristotle had already noted the shifting nature of the horizon in his arguments that the earth was a sphere and not a flat disc, noting in his Meterology that «throughout the habitable world the horizon constantly shifts, which indicates that we live on the convex surface of sphere».16 Macrobius, later, would also

14 Panofsky (1991); White (1957); Arasse (1980; 1999); Damisch (1987); Schlie (2008); Summers (2003); Belting (2009). 15 Koselleck (1989), 349–375. 16 Aristotle, Meteorology, 365a30; the horizon similarly defined is also a basic part of Aristotle’s geometric discussion of the rainbow (ibid. 375b16–377a28), which provided the basis for subsequent arguments; see for example the early 14th-century Theodoric of Freiburg: Freiburg (1974), 435–441. For Aristotle’s arguments concerning the sphericity of the earth, see De caelo, 296a14–298b21.

Introduction 15

write that while the horizon’s specifics are fixed in terms of how far one can see (e. g., 180 degrees), the boundary of the horizon nonetheless obviously moved with the body of the observer. It remained both a constant and constantly mutable fixture, including new elements while others were discarded as they fell out of sight. From Antiquity onward, if not earlier, it can be assumed that the word takes on a cultural dimension associated with the body. In Greek, the verb horizein (ὁρίζειν)means to stake boundaries, limiting space through marking, for instance when one makes a settlement and defines it with a fence.17 This fence would be denoted by the noun horos, which could refer to natural phenomena like mountains, but also to borders and frontiers. Whether the boundaries are «natural» or manmade, in either case they denote a difference between two zones: inside and outside, a delineation manifesting itself in cultural, or anthropological and corporeal terms. Highlighting these anthropological and bodily aspects of the word, it is worth noting that it also stems from the Greek expression ὁ ὁρίζων κύκλος, meaning the circle of the face, as well as ὁρίζω, which denotes the act through which this circle is defined – again a reference to visual and cultural markers that rotate, like a circle, around the individual.18 This encircling band, however, was not limited to earthly bodies, but, as we have seen, was understood to extend outward into the macrocosm of the harmonic celestial spheres. Because the horizon was also the boundary between earth and sky, it was part of a set of circles that reached from earth to heaven, each one marking a specific region that was at once thought to be spatial and philosophical (the circle of the zodiac, for instance). The horizon was thus at the same time macrocosmic, deeply linked to what was beyond visual perception, and microcosmic, since it delimited in a very concrete sense man’s experience on earth; it was a spatial given, but also a cultural artifact. Moreover, it lay, as the Bishop of Nemesios of Emsea (around 400), in turn has written, at the «border between reason and sensation» (ἐν μεθορίοις ἐστὶ νοητῆς καὶ αἰσθητῆς οὐσίας), as well as «the border between irrational and rational nature» (Ἐν μεθορίοις … τῆς ἀλόγου καὶ λογικῆς φύσεως), and the boundary between mortality and immortality.19 «Inside» and «outside» could be construed not only as denoting here and there, but also as dividing spiritual and psychic interiority from the external sensual world. In the Latin West in the thirteenth century (one century after de Lille and the illumination of St. Cuthbert’s death), Thomas Aquinas thus used the Latin word confinium as a translation of the Greek word horizon to denote the border between earthly corporeality and the soul’s ultimate voyage to a spiritual realm beyond the body. Experience within the horizon, Aquinas implied, was just one part of the soul’s much larger and longer voyage, a hinge between mortality and everlasting life.20 These ideas travelled far. In the political anthropology of Dante’s (1265–

17 «ὁρίζειν» in: Liddell/Scott (1940). 18 Ibid. 19 Nemesios von Emesa, De natura hominis c. 1 = MPG 40, 508 and 512. 20 Thomas von Aquin, S. contra gent. III, 61, hg. C. Pera Nr. 2362; II, 81 = Nr. 1625; und In 3. sent., prol.; S. contra gent. II, 68 = Nr. 1453; citation after Hinske/Engfer/Janssen/Scherner (1974), col. 1187 f.

16 Lucas Burkart and Beate Fricke

1321) Monarchia, for example, this hinge-like aspect of the horizon comes to the fore when the author describes it as the limit between «earthly paradise» and «celestial paradise». In using the borrowed Greek word (orizon) instead of the Latin derivation (finiens), Dante not only carried on ancient and medieval philosophical traditions, but at the same time transformed the horizon into a parable of human nature: «man would be correctly compared to the horizon by philosophers, because both stand between two hemispheres» (… zu Recht würde der Mensch von den Philosophen mit dem Horizont verglichen, der zwischen zwei Hemisphären steht).21 For only man, of all God’s creatures, possesses two parts (pars essentialis), a mortal body and an immortal soul. Thanks to this unique nature, Dante continues, man also pursues two goals. On one hand, the realization of happiness in this life, a task accomplished by developing his unique ability to reason and thereby attain «earthly paradise».22 On the other, man also strives towards happiness in eternal life, something achieved in visio beatifica, where only faith can lead. Dante’s conceptualization of the horizon as a dividing line between terrestrial and celestial paradise is only one important example of how the horizon line could be deployed either in a philosophical or a pictorial/spatial sense – or both at once. In different epochs and different cultures, countless possibilities existed to think through the meaning of the horizon and using it as a vehicle in order to locate the position of mankind in larger constellations of space and time. Here, we have only briefly touched upon the late medieval moment in the Western tradition, excluding even the most important later theorists of the horizon in the West from Giordano Bruno (1548–1600) to Leibniz (1646–1716), to Kant (1724–1804), to Heidegger (1889–1976) and Husserl (1859–1938).23 Looking beyond the West, the volume of perspectives on the horizon is even more expansive, not to mention moments in which cultural traditions intersect and inform one another, calling new types of representation and new conditions of philosophical possibility into being across cultures. In these moments, when cultural horizons cross, the question of whether the horizon functions as a barrier or a bridge emerge with heightened urgency. Does one mode of thinking the horizon simply subsume the other into

21 Dante (1989), 241 f. 22 On Dante’s anthropology see the last chapter of Kantorowicz’ pivotal study entitled «Man-centered kingship: Dante» Kantorowicz (1957), 451–495. 23 Bodemann (1895), 83. Leibniz discusses the horizon in the context of the scientia generalis in De l’Horizon de la doctrine humaine. The limits of knowledge apply also to Leibniz the contemporary horizon of science, about a shifting regard future horizons demarcating the expansion of knowledge cannot be speculated. (Et quaevis mens horizontem praesentis suae circa scientias capacitatis habet, nullum futurae, Ettlinger (1921), 33.) For the further developments in the thoughts of Chr. Wolff, G. F. Meier, and A. Baumgarten see Hinske/Engfer/Janssen/Scherner (1974), col. 1187 f. McGrath (2008), 36; Flécheux (2014); Jullien (2014); Anderson (1992); Boehm (1989); Otagiri (2014). Husserl distinguishes an interior horizon of the single thing from an exterior horizon. Husserl (1954), 28 f. Later, Heidegger emphasizes the transcendal meaning oft he horizon to retract statements about transcendence. «Der H. und die Transzendenz sind somit von den Gegenständen und von unserem Vorstellen aus erfahren und nur im Hinblick auf die Gegenstände und unser Vorstellen bestimmt.» Hinske/Engfe/ Janssen/Scherner (1974), col. 1187 f.

Introduction 17

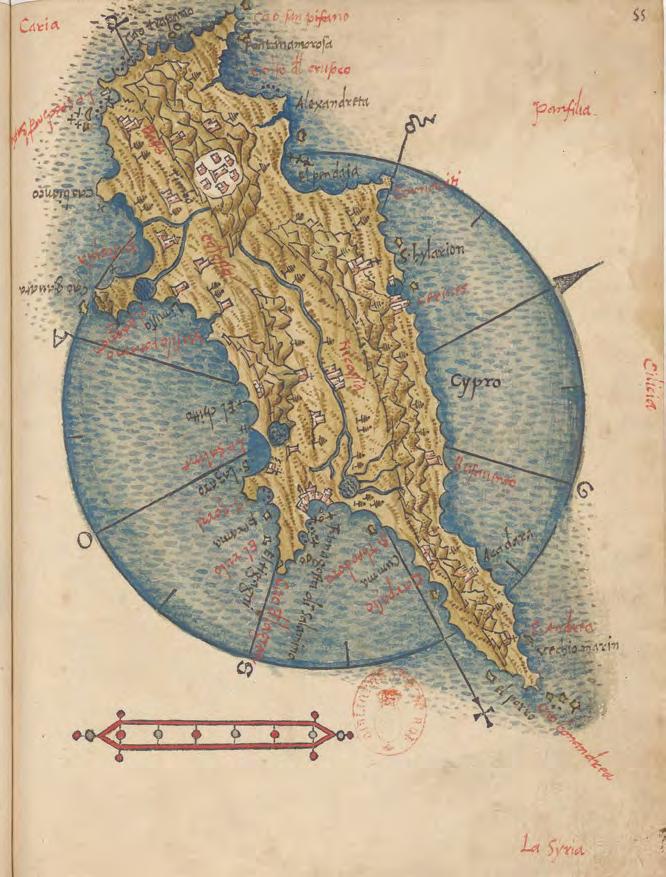

its purview or does the intersection produce a shift, setting in motion new definitions and understandings of time and space on both sides of the line? To close this introduction, we will turn to another late medieval European object that speaks to some of these ambivalences in visual terms: Bartolomeo da li Sonetti’s nautical atlas from 1485.24 We will just briefly address the innovative aspects of his atlas nautique and what they add to already established pictorial modes of representing the visible world.25 Let us focus on the page representing the island of Cyprus26 (Fig. 2). Bartolomeo’s atlas nautique continues the tradition of Islamic and Western medieval portolan charts depicting coastlines, towns, lighthouses, and mountain ranges that helped guide sailors along coasts and avoid obstacles such as shallow waters and reefs. Generally, portolans presented a cartographic overview, combined with labels marking coastal landmarks in a fashion that encouraged the viewer/user to turn the map around in his hands, as if s/he were moving along the coast in a particular direction (the direction being decided by the orientation of the scripted labels). In Bartolomeo’s atlas, we also find a new dimension of representation added to the portolan format. For whereas portolan maps generally present a unified, cartographic surface, Bartolomeo’s renderings combine the portolan’s cartography with chorography, or a rendering of the island in question as a bird’s eye view landscape, so that two visual formats meet in a single image. We can thus make out the nautical chartlike elements which guide the eye (and the sailor) around the island’s coast, but also assume not one but two fictive viewing positions from above (showing us the island in both cartographic plan and chorographic elevation simultaneously). These positions, in turn, conflate with the form of a compass, overlayed as a circle over the island. Meanwhile, these mapped renderings are interspersed with seventy sonnets describing the maps, extolling the particular qualities of islands like Cyprus, supplying an abridged history and describing the natural resources and manufactured goods to be found in each location. These multiple, overlapping visual and epistemological registers are remarkably fluid: they position the viewer both along the coast and above it as well as in the inner regions of an island, equipped with information one would want in order to seek out the bounty the island could provide through trade, or plunder.

24 An important predecessor is the Liber Insularum Archipelagi of Cristoforo Buondelmonti, composed between 1420 and 1422. A contemporary project was the Insularium Illustratum by Henry Hammer, who was active as a cartographer between about 1480 and 1496 in Florence. 25 Michalsky (2011); Krüger (2000); Hofmann (2019); Helas (2010). 26 «This is that Acamantis which charmed so much delicate and tender Venus. Anciently it was called Amathusia and Macaria, now Cyprus. It lies thus – see! on the side where the sun rises it is set over against Syria, and on that where it sets towards Caria; with its plains and hills sloping more towards the north-west, so that the winter blasts are hushed. It is like Crete in size, and lies open to almost the same winds. Of old it held more than one kingdom. Here are sugar, much salt, and wealth, for Ceres showers here store of grain. Here a wine black when made grows light of itself. Here the women are not chary of their favours. Here Paphos and Salamis were renowned: and we hear of Tamassus and Soloi. Here Buffavento looks to every side. Lydinia, Citium, Carpas and Constantia, Famagusta, and Nicosia, seat of kings.» Excerpta Cypria (1908), 50.

18 Lucas Burkart and Beate Fricke

Fig. 2: Isolario de Bartolomeo da li Sonetti atlas nautique datant de 1485 70 sonnets bnf.fr/fRl vue 115, Cyprus.