2 minute read

Research & Influences

At its heart, this work is a fusion of art and science. It is critical those scientific foundations are from reputable sources. The World Health Organisation and Wellcome are two such examples. I will also employ publicly available evidencebased research and the support of medical and scientific professionals. As I explore the science in the context of photography, organisations such as the Too Tired Project, the Arts & Health Hub, and podcasts such as The Long Time Academy are content-rich resources.

Helping to navigate the medical and anthropological science, authors such as Dr Gavin Francis and Vybarr Cregan-Reid are proving invaluable, whilst the likes of Leonardo da Vinci, Jane Austin and Ovid’s Metamorphoses are informing early image ideas.

Advertisement

Rinko Kawauchi’s imagery, and its ability to connect to our collective unconscious (Takazawa 2016), has provided initial inspiration for the visual language. Their often delicate fragility convey the beauty of her subject whilst revealing a sinister undertone (Parr 2004) and it’s this juxtaposition I’m keen to explore. Similarly, I’m drawn to Richard Misrach’s work, who writes “beauty can be a very powerful conveyor of difficult ideas....it engages people when they might otherwise look away.” (Misrach 2020: 86). Misrach’s use of blue water barrels in Fig.4 to signify the emotionally-charged migrant crisis at the US/Mexican border makes a compelling and moving image.

Elena Brotherus’ Carpe Fucking Diem, Lisa Graves’ between breaths and Laura Marsh’s Occulta have brought visibility to the invisible. As I look to do the same for the many invisible impacts, medical imagery is one option. The rarity with which we see those (Orton 2018) and the concept of the medical gaze could be a key driver in generating audience discussion. At risk of looking beyond the scope of this work, I’m also drawn to Helen Sear’s Composities, which combines “multiple images to emphasis the indivisibility of the human and the natural worlds.” (Centre for British Photography 2023).

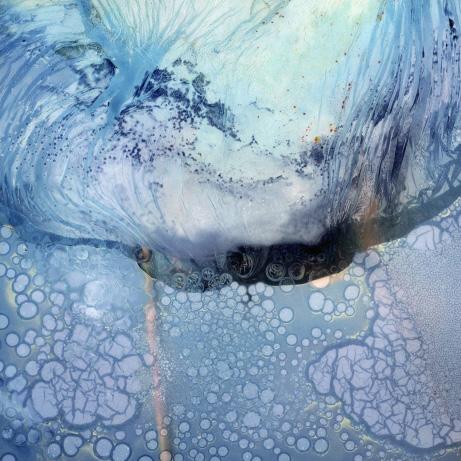

The main body of the work will be taken digitally, but there are impacts at a cellular level that I’d like to represent differently. Naomi James’ Lockdown Decay and Phillip Stearns’ High Voltage Images convey an intriguing visual quality.

Employing Polaroids differently, they both introduce an element of chance into the final image; an analogy for cell division I’m keen to use. Such images will be an entirely new venture and one requiring experimentation in order to produce something visually compelling. Rhiannon Adam’s Polaroids: The Missing Manual will guide early tests, whilst Naomi James has been kind enough to offer advice as I embark on this phase.

More personally challenging is the inclusion of text; something I’ve not done before. Although apprehensive, I think it’s an important element to complete the work. I envisage the images being accompanied by insight into my narrative and the health impacts each image represents. Quite how I blend images and text is currently undecided. The tension created by Anna Fox in My Mother’s Cupboards and My Father’s Words is very powerful. Conversely, the separation of text and image using, for example, an accompanying catalogue allows for an initial reading of the image without any additional context. Although not created for an exhibition but as part of a photobook, I was struck by the use of text by Rhiannon Adam in Big Fence/Pitcairn Island. The potential to include an essay further complicates the decision but may support the longevity of the work after the exhibtion’s culmination.

How these series of images and text work together will emerge over the coming weeks, and the editing and sequencing of the final set will be a critical part of that success.