42 minute read

We just hope it knows when to stop

By Daniyal Ahmad

Karachi, is a city of contrasts. Its dusty streets and bustling markets are offset by the cool, salty breeze that rolls in from the Arabian Sea. However, this coastal environment has also taken a toll on the city’s public transportation system. The once-vibrant potpourri buses, which used to weave through the city’s dusty streets, have now rusted and crumbled under the weight of time and salty sea air. The heat and humidity that come with the location make for an uncomfortable commute for many, especially women, who are subject to routine harassment and objectification on the city’s crowded and often unsafe buses.

Advertisement

However, amidst the crowded streets of Karachi, a stark contrast to the grey, polluted surroundings, bright fuschia buses have suddenly sprung up. These buses dot the busiest centres in Karachi. They disrupt the melancholy of everyday travel, and spark curiosity about what the City is planning for its future.

The Pink Bus service consists of modern, sleek, and spotless behemoths. They are inviting and forthcoming for the demographic that this city’s transport network has somewhat forgotten. Rivalled only by their sibling, the bright red Peoples Bus Service, the real sur- prise comes to travellers when they step into the bus. Not a man in sight.

Instead, passengers are greeted by comfortable seating, surveillance cameras, and a female conductor to ensure the safety of the passengers. For women who once felt invisible on the unisex buses, these pink buses are a symbol of empowerment, a reminder that they deserve to feel safe and secure while travelling around their city. Segregated public transport is not a novel concept. It exists across the globe in countries such as Brazil, Mexico, and Japan to name a few. It’s also been tried in Lahore, Peshawar, and most notably in Karachi as well previously. However, the hype around this particular government intervention has particularly created buzz. If for nothing else, then it might be for the fact that it comes to one of the very few world’s megacities that is still starved for public transportation. Or maybe, the fact that, for Rs 50, women now have an additional affordable option for commuting at a time when Pakistan is experiencing one of its highest periods of inflation.

“It’s a grand effort on their part. It’s a lot of investment as well, Karachi has never seen investment like this before in terms of transit,” Sana Rizwan, Dean’s Fellow at Habib University, Karachi, tells Profit. Similarly, “A perennial problem for Karachi is that public transport is something that has been sidelined. I think this is a positive step when you think about it from a public transport perspective,” says Dr Hadia Majid, Associate Professor at LUMS.

However, what is the purpose of the Pink Bus? Profit called Sharjeel Inam Memon, Minister of Transport & Mass Transit for Sindh, and Murtaza Wahab, Former Administrator Karachi, to ask them that very question. However, both chose not to respond despite repeated efforts.

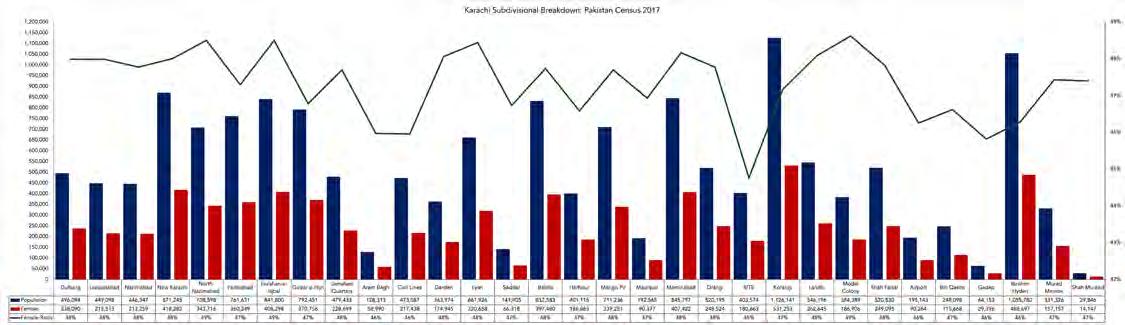

So Profit decided to explore the answer to this question ourselves. The simple answer is that it aims to get women from one area to another. But this answer is lazy. If that were the case then they would at least have a stop in the New Karachi or Lyari subdivisions of the city. Why do we highlight these two in particular? Because, according to the National Census of 2017, the former has the largest female population of Karachi whilst the latter has the most densely populated. We don’t think this omission is by any means a mistake.

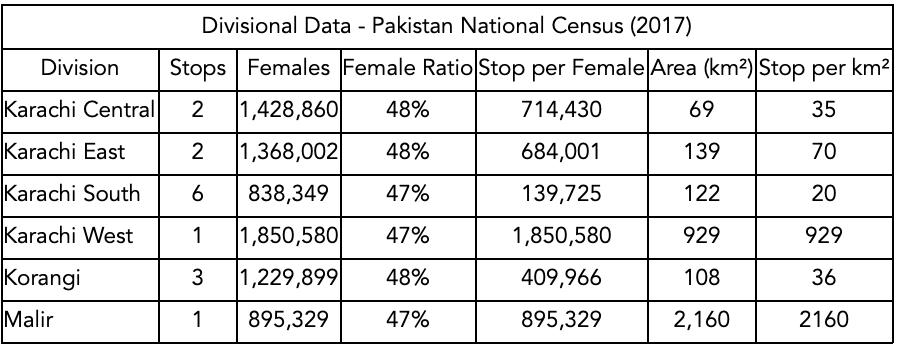

The buses increase in frequency during rush hours, and reduce during normal hours. Karachi South, the closest thing Karachi has to a business district, has six out of the total 15 stops. Where are we getting at with this?

The most likely aim of the Pink Bus service is to spur economic activity across Karachi. Why would anyone want this? Well, Mosharraf Zaidi estimates that higher female workforce participation could boost Pakistan’s gross domestic product (GDP) by $80 dollars.

Is there a link to female labour force participation, and transport though?

According to research conducted for this piece, the International Labour Organisation, the Asian Development Bank, the International Growth Centre, and the World Bank all highlight restrictions on female mobility as reasons for reduced labour force participation. A 2007 study by Dr Mehak Ejaz also found that owning a personal vehicle to be positively correlated with increased female labour force participation. So the link between female labour force participation and female mobility is undeniable.

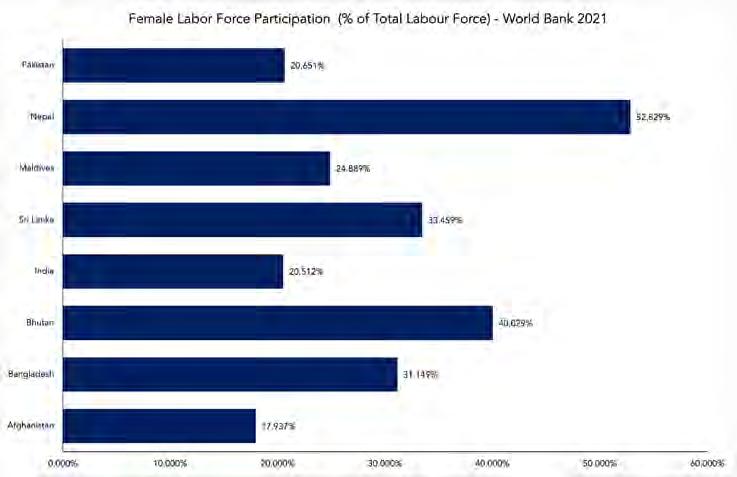

At 20.651%, based on estimates by the World Bank, Pakistan has the third lowest female labour force participation in South Asia. Thus, it has a long way to go in terms of realising the economic potential of its women. But will the Pink Bus lead to an uptick in this metric in Pakistan’s most densely populated and urbanised city? The answer to that is not as simple as we think. It, surprisingly, also leads to previously unimagined problems by opening news cans of worms.

Transport and female labour force participation

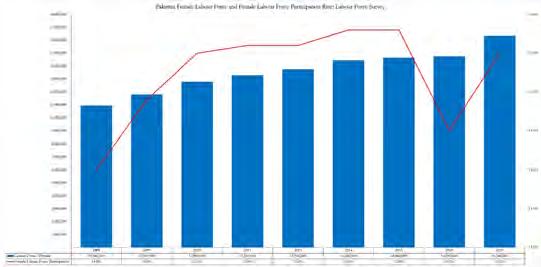

To begin with, let’s examine the composition of the female workforce in Pakistan. According to the 2020-21 Labour Force Surveys, the country’s overall labour force amounted to 71.76 million, out of which women comprised 1.684 million, or 23.47%.

While this may not be an alarming figure, a deeper analysis of the data reveals a stark reality. The manufacturing industry and domestic work as household employees employ the largest number of female workers, both of which are generally low-paying sectors. In fact, only a small proportion of female employees, 5.29%, earn monthly wages of Rs 15,000 or more.

This is particularly concerning when we consider the cost of living in Pakistan. With the average cost of a small car in Pakistan being upwards of Rs 2 million, owning a car is a luxury that is out of reach for many people earning less than Rs 15,000 per month. Therefore, if you’re a working woman in Pakistan who happens to own a car, you are among the minority in the workforce, highlighting the economic challenges faced by women in the country.

In the absence of their own vehicles, public transport is the modus operandi. This is where all of the benefits of the Pink Bus come into play. “Having transport, not just public transport, which helps you get to your workplace is important. The lack of affordable and

Samina Farooq,

safe transport limits the radius of job search that women can do. The number of multiple jobs they can have also becomes limited,” says Majid.

“There are two categories of women the bus will help. The first are those who primarily stay inside their homes. These women will say that the patriarch of their house caters to their mobility because of the fear of harassment. The patriarch will likely say that they can drop off the woman on his way to work, or allow her to work wherever he’s employed due to that fear,” Majid tells Profit. “Then there are women who are already part of the workforce. There are very clear benefits for them because of the bus service. Furthermore, the bus better enables them to attend training sessions. There is likely to be an uptick of conventional and vocational training sessions attended by women within the workforce because of this,” Majid continues.

Similarly, “Women who are less likely to use transit because of the fear of harassment, will be more motivated to use this. Families that don’t allow women to travel on public transport because of the fear will be less likely to stop that because they’ll be told that it’s women only, and thus there will be no harassment,” says Rizwan.

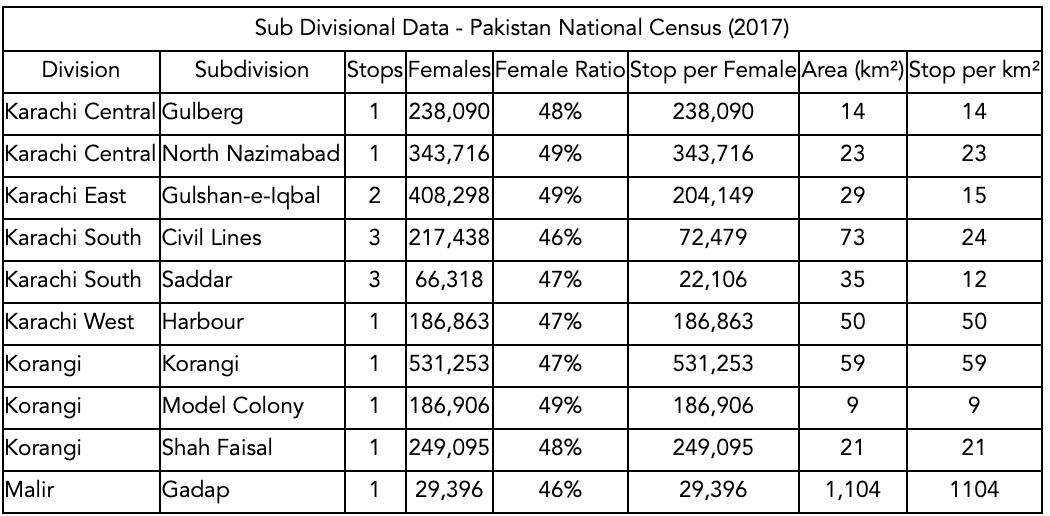

The Pink Bus is also meticulous in the routes that it does cover to cater particularly to women. Profit utilised Pakistan’s 2017 census to understand how much of the female population the Pink Bus does serve. Across its 15 stops, the Pink Bus Service theoretically accommodates 32% of the female population across Karachi’s different divisions and subdivisions. Furthermore, its stops cater to three of the 10 subdivisions with the highest gross female population and four of the 10 subdivisions with the highest percentage of females relative to the total population. The former is achieved by its stops in the subdivisions of Korangi, Gulshan-e-Iqbal, and North Nazimabad. The latter on the other hand is served through the bus’ stops in the subdivisions of Gulshane-Iqbal, Model Colony, North Nazimabad, and Gulberg. All of this is within two months of the bus’ launch, with more buses and routes expected to follow in the months to come.

Looking out for our most vulnerable

The Pink Bus also adds quality of life improvements to female workers in their journey to and from work. Particularly those that are most vulnerable when in the public sphere. “First, and foremost, female domestic workers live in joint families due to the cost savings. When these women step out of the house, and there are no definite public transport routes, their households will always make snarky comments about their character. They’ll attribute her journey to work as leisure,” Samina Farooq, Presi- dent of the Pakistan Domestic Workers Union, tells Profit. The struggle only worsens for these women once they do leave their houses.

“Rickshaws, and qingqi’s in particular, are unsatisfactory modes of transport. In qingqi’s, the drivers and men will constantly turn their heads whenever they can to ogle at the women. If they’re sitting next to the men, then the men will touch them inappropriately. All of this can be avoided on buses because they have dedicated cabins for women but it is not possible on a rickshaw,” says Farooq.

“Rickshaws are also very costly. Getting from one place to another can cost up to Rs 100. Rickshaw drivers also exploit riders in unique ways. Sometimes they’ll refuse to give change to customers stating tootay nahi hain humaray paas. Once they have refused to provide the change, they’ll unofficially raise the fair. The next time the woman pays in change, they’ll argue how the customer gave them Rs 50 the previous day and thus Rs 40 is no longer acceptable. This is not a cost that a domestic worker can bear easily, and regularly,” Farooq continues.

The horrors that domestic workers have to face are not only limited to their journey. “In the absence of public transport, domestic workers will have to search for rickshaws. Even when the woman has found a rickshaw, she will have to wait because the rickshaw driver will refuse to depart until they have utilised the available capacity for all six potential riders,” Farooq says, adding that this often results in punishments at different levels of severity.

“With this stress hanging over their head all day, they’re likely to make mistakes during their routine tasks which in turn leads to more punishments. Some of the employers… will deduct the domestic workers’ pay for arriving late, or make them stay later and do excess work. If the pay is deducted once or twice, the woman will simply abandon her private life, and leave her house earlier in the morning for work. This is even more problematic because these women are expected to take care of the children, and make breakfast for their husbands before they head off for work. An employer does not take into account any of this,” Farooq continues.

These problems are unique to female domestic workers, as male domestic workers have it better according to Farooq. “Some men pool together funds to get to and from a destination on their motorcycle. One will pay for the fuel on the way there, whilst the other will pay for refuelling on the return journey. Societal norms simply do not provide women with this facility,” adds Farooq.

The Pink Bus, thus not only increases a women’s participation in the economy, but also reduces their daily expenditure, and most importantly, provides them with the dignity other modes of transport simply do not currently. However, the bus is far from any panacea. There are many areas where it still has a ways to go.

We’re not there yet

The most glaring problem with the Pink Bus is the lack of stops. At a total of 15 stops across Karachi’s six Divisions, and 31 Subdivisions there is a serious problem in terms of logistics for prospective passengers.

Karachi has six Divisions that encompass a total female population of 7.611 million across a total distance of 3,527 km², based on the 2017 Census. This amounts to one stop per 782,339 females, with each stop catering to a whopping average area of 542 km² for the female population. The statistics are only marginally better at a Sub-Divisional level. With 31 subdivisions, each stop caters to an average of 206,405 females over an average distance of 133 km². The disparity in divisional and sub-divisional data is due to the difference in the number of stops available per division, with many divisions having more stops than others within their subdivisions.

There are also various subdivisions that are not entirely served at all. In terms of gross population, Ibrahim Hyderi, Baldia, Gulzar-e-Hijri, Ferozabad, and Mango Pir are glaring omissions. Similarly, the subdivisions of Garden, Landhi, Liaquatabad, and Lyari are not served despite having high female ratios relative to other regions of Karachi. Mominabad, and New Karachi fall under both aforementioned categories and remain unserved as well. Now, one can argue that such a cri- tique is premature for a project that is still in its infancy. However, when you’re catering to women in particular, logistics is crucial. “You have to look at the fact that mobility is not just about the bus itself. It’s also the way that you acquire access to it, and how it transports you,” explains Rizwan.

“To me as a woman who travels in public transport, my biggest concern is not that I will have to overcome harassment in a bus. It is that as a resident of Karachi, I am in greater danger when I am waiting at the stop for the bus itself,” says Rizwan. “Where does the bus stop? How long does it take for the next one to come? How far is it then from the place that it would potentially connect you to? Transit is a holistic journey. You have to look at the first mile, and the last mile. How are you connecting them in the first place? Will there be a rickshaw or qingqi waiting there to transport passengers or will the passengers have to traverse large distances to reach their final destination after getting off? Will the patriarch of the house have to wait at the stop when you return?” Rizwan continues.

She is not alone in her concern about the first and last mile, particularly if the bus does not allow passengers to reach their final destination. Farooq echoes similar concerns, “When women leave their homes in search of transportation, there are men standing in various alleys and corners in the street just to ogle them. They have to encounter these men both when they leave and return home. The problem is so prevalent that you have lots of unemployed men who’s full-time job can simply be considered ogling women who pass by. They even identify areas which women are more likely to use,” adds Farooq.

“These poor women leave their homes in search of livelihoods, and have to face men such as these,” Farooq continues. “You have to look at the whole journey. If I am a woman waiting for a bus, and every little thing in the environment works to turn me into a sexual object, it does not protect or cater to me, I don’t want to stand there anymore which is why I’ll be like, okay I’ll spend extra money to get a private van service, a rickshaw, or an uber, or whatever I can afford,” says Rizwan

The answer then is to just add more stops then, Right? Not really.

A bandage rather than surgery

More stops might not really encourage more ridership for a myriad of reasons.

“You have created this binary about women. Are women more likely to travel without their children? Are they more likely to travel without their brothers? Are they more likely to travel without their fathers? Are they more likely to travel without their families? Is this just for a single woman who is working? What if a woman wants to pick up her children from school? Should she then take a separate bus? How is the bus catering to all of this?” Rizwan asks.

Also, “When you have a city government that is already strained for resources, how do you want to go about managing this in a constructive way so that an overall larger population is served?” Rizwan muses. This is the double-edged sword that the Pink Bus will have to contend with. On the one hand it will have to grapple with the realities of fiscal realities, whilst at the same time undertake the herculean task of mobilising women across Karachi.

Specifically, restricting potential ridership by utilising gender segregation is unlikely to help with the fiscal feasibility of any mass transit project.

“If the point is to increase labour force participation rates, then I find it doubtful. There is work in the Pakistani context which suggests that women suffer a great loss of identity if you force them to work,” Majid tells Profit. There’s a lot of other stuff going on which we need to look at. When there’s a holistic intervention, only then will you see an uptick in labour force participation,” Majid continues.

What entails holistic interventional steps? “We really need to move towards a normalisation of women in the public sphere. A normalisation of women using public transport. The idea that they belong here, and have a right to be here,” Majid elaborates.

Farooq opines similarly. “When a woman leaves her house, she should be able to do so confidently with her head held high so that no one is able to question what she’s doing in the public sphere.” The cultural aspect of the project is one that cannot be ignored, because the bus by its very design serves a broader cultural purpose as well. Referring to Mexico City’s women only subway carriages, one of the global poster children for segregated transport, Rizwan highlights how the measure was complemented by the government undertaking educational reform to reduce incidences of harassment, and encourage female ridership.

“When a woman actually uses transit, and cannot go on a pink bus for whatever reason, and she faces harassment then what is the indication of that? Will she be blamed for not travelling in the Pink Bus? It then also limits women’s participation in that mixed bus because a lot of women will wait to only take the Pink Bus,” Rizwan. Similarly, Majid argues that ignoring the cultural dimensions of female participation in the public sphere will just “ghettoise” the issue.

So where does that leave us?

Profit spoke to Dr. Nida Kirmani, Associate Professor at LUMS, to get a final verdict on the matter. “Segregated transport allows women to feel more comfortable accessing public space. In the short term, this could help encourage more women to use public transport without fear of harassment. In a context where this is a harsh reality, segregated transport offers a stop-gap solution. However, segregation also reinforces the idea that women and men should occupy separate spaces and that men cannot control themselves from harassing women,” Kirmani tells Profit

“In the long term, one would want to gradually shift to public transportation in which people of all genders feel comfortable being in the same space. However, offering segregated spaces initially may help gradually change the culture in the long term,” says Kirmani.

The Ouroboros is an emblematic serpent of ancient Egypt and Greece represented with its tail in its mouth, continually devouring itself and being reborn from itself. It is the perfect depiction of how a problem begets another problem. Public transport needs as much ridership as possible to reduce the cost on the exchequer, and therefore it is done on a large scale to reduce the per rider cost. Segregated transport would need to be done so in an even larger manner, because it is naturally exclusionary and therefore cannot take advantage of all the potential riders that might choose to utilise it. However, If greater numbers of women are mobilised and greater economic activity is generated then it might be worth it. Maybe then the social benefit will outweigh the private cost? But that is debatable. n

By Abdullah Niazi

Over the past one year, one of the largest conglomerates in Pakistan has been silently diversifying its interests. From water-treatment to fintechs, pharmaceuticals and banking, the Descon group is looking to expand beyond engineering, power, and chemicals. But one of their most interesting investments is coming in a sector largely ignored by Pakistan’s big-guns: Agriculture.

The beginning has been slow. Descon’s foray into agriculture has been committed but cautious. The conglomerate has, for example, invested in a few existing export-oriented companies. One of these projects is a Himalayan Pink Salt and Himalayan Honey export venture. They are also in the initial phase of setting up a dehydration plant in Sheikhupura. But selling salt and honey is only the beginning of Descon’s ambitions.

In March last year, the company acquired shareholding in two budding agricultural enterprises — Vital Agri Nutrients (VAN) and Vital Green (VG). Since then, VG has gone on to partner with microfinance bank FINCA to provide financing to farmers who are part of their value chain. Meanwhile VAN has also been providing bespoke solutions to farmers facing problems like infertile soil. In November 2022, the group set-up “Descon Research Farms” — a dedicated 100-acre farming facility near Kasur meant to experiment with new farming techniques and test the interventions being proposed by VAN.

For Pakistan, this marks an important milestone. Despite being the largest sector in our economy, agriculture has been largely forgotten. These recent investments show that Descon seems to want to put money in the most critical problems that face our agricultural sector, and position themselves to be a major player in farm agriculture over the next eight to 10 years.

The good news for them is that the field is clear and there are no real competitors. However, Descon’s strategy is one of slowburn. And with the macroeconomic situation going from bad to worse, could this expansion be stopped in its tracks? Profit sat down with Faisal Dawood, Vice-Chairman of Descon Engineering, to try and understand the reasoning behind venturing into agriculture at this time.

The crisis in our farming

There are essentially three problems that face Pakistan’s agriculture. The first one is a complete lack of research and development. Over the past seven decades, Pakistan has barely introduced any new seeds, area under cultivation has grown but yields for most crops have not grown proportionally, and farm mechanisation rates have remained historically low.

The second problem is the supply chain management. Storage facilities are difficult to find, the government regularly has to offer support prices or buy directly from the farmers, and short shelf-lives means a lot of our agricultural produce goes to waste. And the last problem is a lack of agri financing. Banks and other financial institutions don’t seem to trust or understand crop cycles and offer horrible terms and demand collateral in exchange for loans.

All of this means that farm profitability and agricultural outputs have been middling at best and tragic at worst. Here is the thing — overtime Pakistan’s food security woes are going to get worse. Already the country has become a net importer of food and catastrophic flooding caused by climate change last year has badly exposed the fault lines that exist in our teetering ‘agrarian’ economy. That means getting into the business of agriculture right could prove a prudent measure. With international prices fluctuating wildly over the past few years, food scarcity and inflation could increase for local produce as well. Farmers who tackle the core issues will be well placed to benefit from this.

Essentially, these are what the three problems boil down to:

• A lack of focused research and development, and modern innovations that hold us back from producing export quality produce at high yields.

• No reliable agri financing that can provide farmers the opportunity to invest in their land and try to experiment and grow their farm sizes and introduce modern techniques.

• Supply chain issues and shelf-life that results in wastage

In their recent path to try and expand into agriculture, in one way or another Descon is trying to get a foothold into all of these issues. So let’s break them down one by one.

The research conundrum

Of all of Descon’s recent investments, perhaps the most interesting have been VAN and VG. Vital Agri Nutrients (VAN) is an R&D-driven company engaged in the production of specialty fertilisers, micronutrients, soil amendments, and a range of other products aimed at making agriculture more productive and sustainable. Essentially, if you have a farm and are facing problems such as low productivity and low yields, VAN provides bespoke solutions.

Already the company has a number of products like NPK blends, organic soil amendments, micronutrient blends, biofertilisers, and specialty chemicals designed for water retention in the soil. With a manufacturing facility on the outskirts of Lahore that houses equipment for organic fertiliser bulk production, liquid fertiliser, granular fertiliser, and bio labs. Other facilities include a modern laboratory, filling plant, and warehouses. The facility also has trial fields for the testing of products under various controlled conditions.

“We have invested in a company by the name of Vital Agri Nutrients, which is essentially a specialised fertiliser and micronutrient company. They provide solutions by taking soil samples and testing deficiencies of the major nutrients,” explains Faisal Dawood, Vice Chairman of Descon, who has been the leading light of the Descon Agri Business (DAB) division. “We are currently working with more than 10,000 farmers. The goal is to decrease input cost and also if there is not a deficiency then tailoring the fertiliser. Essentially a lot of research and scientific methodology is required to understand the field and propose solutions.”

Unfortunately, this is exactly what is lacking in Pakistan. The Pakistan Agriculture Research Council (PARC) is a shell of an organisation hampered by a lack of inter-provincial coordination. No private money of note has been pumped into soil studies or farm efficiency methodologies. Descon’s solution to this has been the Descon Research Farm. On 100 acres right off Kasur, the farm is a playground for VAN to try out all of their proposed interventions. The intent was to experiment with various innovative farming techniques on various crops to work towards our mission of transforming the agricultural landscape. The research farm’s first produce of rice from targeted intervention actually managed to achieve better yield and higher nutritional value. However, the farm has its limits. In the grand course of things, 100 acres is a drop in the bucket, and more holistic research is required on a national level.

“The entire point of this is that we want to promote research on a national level. The company is established as a non-profit and the goal is to research at a high level and provide that free of cost to everyone. We need better seeds, better nutrients, better soil, and better farming practices. Descon will obviously benefit from it but the research is there for everyone to use,” claims Dawood. According to him, this is just the beginning and the eventual goal is to synergise Descon Research Farms with VAN.

“We plan to open smaller research farms all over the country. Our goal is to have research stations wherever Vital Agri has outlets. That area is something where Vital Agri can then demonstrate the efficacy of their products. Eventually, we want these farms to be open for anyone that wants to test the interventions and eventually even use the land for experimentation. Our first such research station will be set up by the third quarter

Pakistan also faces a food security problem. Nobody talks about the growing population. Pakistan’s land area is not going to increase significantly. If we decrease the wastage of perishable items then storage and supply chain can be bolstered. We look up to companies like National and Shan foods which have actually managed to change the way people cook. People think if they don’t cut fresh tomatoes and onions for food it won’t be as good but that isn’t the case. Convincing them is going to be the challenge

Faisal Dawood, Vice-Chairman of Descon Engineering

of this year in Sindh and we will continue expanding from there until we cover all of our Vital Agri stores.”

The plan is a long-play. Over the next eight years, Dawood claims that they want VAN to expand all over Pakistan and have at least 80 outlets. That then means setting up 80 small-sized research farms to go with each outlet. Acquiring, committing, and setting up such farms is a herculean task and will likely not be achieved for decades.

“We’ve been at it for three years and have already committed a billion rupees. Land acquisition, technology etc. We have earmarked Rs 30 million for research only. We want to raise money for this research obviously. We are buying machinery. The income we generate from selling the crops will be ploughed back in. So overall the Rs 30 million plus machinery and the value of the land itself.”

A question of loans

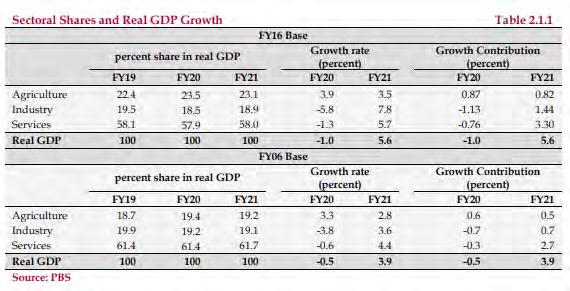

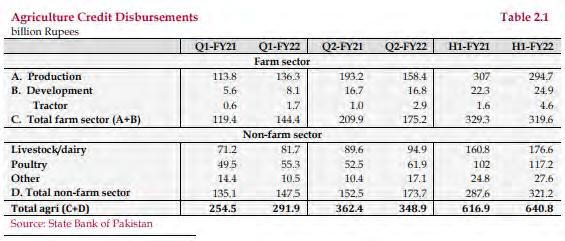

Then we come to our second part. While Vital Agri Nutrients aims to provide research based nutritional interventions for crops, the other major issue in Pakistan’s agriculture is a lack of financing. Data from the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) shows that while credit disbursements to agriculture grew by 3.9% in the first half of FY22, this was mainly due to higher credit offtake by the non-farm sector, as disbursements to livestock and poultry grew by 9.8% and 14.9% respectively. Meanwhile, credit disbursements to the farm sector contracted by 2.9% during H1- FY22 compared to the same period last year, as production-related loans declined by 4.0%.

On this front, as mentioned earlier VG partnered with FINCA Microfinance to provide agri loans to those using their supply chain. Microfinance has been one of the few avenues of financing available to farmers. According to Dawood, Descon has already provided loans worth around Rs 200 million through microfinance institutions almost 100% of which have been paid back.

“As agri financing is concerned, I think that the potential is limitless. We’ve teamed up with various startups. Our goal is not to hand farmers a check. We have done financing worth Rs 200 million and have returned almost 100% of the loans we took through fintechs,” claims Dawood.

“We are looking at traditional banks as well, but there is too much bureaucracy. There needs to be a match between the bank’s product and the understanding of crop cycles. If most banks are giving 30-day loans and a farmer requires 45 days for his crop to be ready and sold to the market, how can he be expected to pay back that loan? On top of this deployment through brick and mortar banks is too difficult now. I would personally not want to push a predatory or 40% loan on any farmer. If I can keep my operating expenses low enough through these microfinance and fintech institutions then we can actually pull this off.”

Innovating on the fringes —- salt, dehydration, and honey

These, of course, were Descon’s long-play solutions. By entering into research and producing their own products to increase yield, the conglomerate is clearly trying to set itself as a private sector leader in farm agriculture. However, interestingly enough, they have introduced two other ventures that are on the fringes of farm agriculture. It might not make immediate sense but Descon, the company that has led numerous large-scale projects in Construction, Power-generation, Oil-Refining, Chemicals and other diverse economic-sectors, is now going to be in the business of selling salt, honey, and dehydrated fruits and vegetables.

The first of these investments is a dehydration plant at the Quaid e Azam Industrial Park in Sheikhupura where they plan on air-drying and dehydrating different fruits and vegetables to sell them as a B2B venture. By dehydrating these products Descon hopes to change the way people cook and consume food by giving it a longer shelf-life and tapping into some of the problems that exist in our agri-supply chain.

For this venture, Descon has teamed up with two other investors and has 70% shares in the project. “We were pitched an idea for a dehydration plant so we started looking around for any such competitors and there was no organised sector and it wasn’t professionally done in Pakistan so we took it on. This was not our own idea, it was brought to us by someone and it was unique enough and just like our other investments it was important to have an alignment with the founder’s values,” says Dawood.

This is a particularly interesting project. On the one hand, the dehydration plant can be used to dehydrate products such as apples and brand them as high-end snacks to be sold at bakeries and supermarkets. On the other hand, there is also the capability to dehydrate products like tomatoes and onions that can then be used in cooking. Since dehydrated products have a much longer shelf life, little packets of onions and tomatoes during the peak price season could go a long way.

This means that for the dehydration product, Descon could be looking at two different markets. On the one hand, they could strike a deal with McDonalds to provide dehydrated apples, since there are many McDonalds outside Pakistan where dehydrated fruits are offered as substitutes for fries for Happy Meals. Then they could also ally themselves with places like Shan Foods or National Foods which have found success in packaging pre-processed everyday food ingredients.

“We are trying to target both markets. One of the reasons is that when we mapped out the calendar of fruit and veg seasons there is a gap that allows us to do both in different parts of the year. If there is an overlap with apples and onions we may not have done that but there is a year-round cycle that exists to our benefit. On the one hand, people are becoming more health oriented. McDonalds offers the opportunity to switch fries with freshly cut apples for kids’ meals for example,” says Dawood.

“On the other hand, Pakistan also faces a food security problem. Nobody talks about the growing population. Pakistan’s land area is not going to increase significantly. If we decrease the wastage of perishable items then storage and supply chain can be bolstered. We look up to companies like National and Shan foods which have actually managed to change the way people cook. People think if they don’t cut fresh tomatoes and onions for food it won’t be as good but that isn’t the case. Convincing them is going to be the challenge.”

According to Dawood, right now the focus is on experimenting with different techniques and ensuring that the product is of a consistent quality. The plant will not be launched until October this year, for which they have imported machines from Italy.

Then there are the export oriented businesses. Descon was approached by a young entrepreneur that was selling Himalayan Pink Salt to the international market and took a 60% share in the business. Initially, the exports were mainly to Singapore but overtime they have managed to expand their market to Hong Kong as well and an initial order is also going out to Lithuania. There is also a Himalayan Honey brand that produces special kinds of honey that are only available in this region because of its unique flora and fauna that the bees feed off. This has given rise to the Himalayan Wellness brand that Descon is trying to grow.

“Our sourcing is from all over the country — KP, GB, Balochistan. Beekeepers move around from season to season. We have a contract with them that they sell their honey to us and we provide them with beehives, medicines because bees are prone to parasite attacks, and we share better practices with them. This is where we’ve also brought tech into the equation. We do not sell in Pakistan but are planning to do so through an ecommerce platform. But on the tech side we are trying to focus on being able to track the honey from hive to home instead of using consumer facing tech,” he explains.

Growth and the macroeconomy

In all fairness, the introduction of a big company into the agriculture sector has been long overdue. All of these investments are direct Descon projects. It is not a project of the Dawood family office or something associated with Descon, it is a direct attempt to enter the largest sector in Pakistan. More specifically, farm agriculture as opposed to dairy and livestock where other big players have entered.

“These are all direct Descon investments. Companies that are 100% owned are branded as Descon but when we come in as outsiders and they already have a strong brand we don’t want to disturb what they have started,” says Faisal Dawood. “We started having conversations about diversification four to five years ago. We took a decision not to reinvest in the sectors we were already strong in and to branch out. Agriculture is not the only thing we have diversified in.”

As Dawood has explained to Profit, Descon has over these past few years invested in water-treatment, it has invested in a pharmaceutical company and a hospital through a pri- vate equity fund, it has invested in fintechs and gaming houses, and the last one is agriculture. “We felt that agriculture is at a similar stage where Descon engineering was at its beginning back in the 1980s — untapped and with limitless potential. Jehangir Tareen is the only big player in the farm agriculture sector. While companies like Nishat have entered dairy and livestock, we felt that it should not be up to Tareen Sahab alone to carry the burden. As such, we are fully committed to the agricultural sector and are looking to diversify further.”

Of course, the road is not going to be so easy. Given the dire straits of the macroeconomy, every sector in the country is facing a crisis and new businesses are more vulnerable than others. Dawood says that after two years he still considers these investments as “startups” and that if they do not get 200% growth for the next eight years then they will not have met the mark. However the problems they will face will be daunting.

Just take a look at their initial investments. For the dehydration plant, imported machinery may face delays in arriving because of LC issues. While the machines may get a pass because food is an essential item, it is not clear how it will play out. On the Himalayan Pink Salt issue, Pakistan has not done a good job with branding. Much like with Basmati rice, India repackages pink salt and sells it as an Indian product even though Pakistan is the only source of Himalayan Pink Salt. There are, of course, some benefits as well. Export oriented businesses will benefit right now from the exchange rate situation. “We also have plans to synergize our businesses. For example, for our Pink Salt line we have a number of products such as pink salt with lime or with chilli. We can incorporate our dehydration into this as well,” explains Dawood.

At the same time, a big challenge will be remaining committed to continuing research and development.

”In the next decade we want to be exporting to at least 50 countries. The dehydration company needs to stay export focused given the current forex situation. On the research farm, if we can see an impact on 2000-3000 acres that will be a big plus. We also want to increase our VAN outlets to 80.”

Descon’s plan is an ambitious one. It will require commitment which up until this point they have shown. However, it is early days, and the way Pakistan’s agriculture sector is setup means that there will be a number of failures before this can be scaled up to a stage where its true potential is unlocked. To that, Dawood seems content, and that may prove to be a smart strategy. “Yes we might face failures. The important thing is that we’ll get up again and learn from them. That’s how we built Descon Engineering in the 1980s and we can do it again with agriculture.” n

By Nisma Riaz

Have you ever experienced crippling pain along with extreme mood swings that made you feel like you’ve lost control of both mind and body? And despite this hell breaking loose within you, have you ever ‘(wo)manned up’ and gone to work?

If not, you are probably one of the lucky ones or maybe, you are a man. If yes, you should have been allowed to take a sick day, or two.

If Covid-19 has taught us anything, it is that the 9-to-5 grind is not the only possible model for working; there can be various other, and even more productive approaches to work schedules. We tend to forget that these hours were born out of necessity of the economic circumstances of the early 20th century, but that is not the natural order of things.

The world was forced to reset after the pandemic, transforming to accommodate the labour force better. In the post-Covid world, countries are moving towards remote working, flexible work hours and four-day working weeks, which has proven to improve employee satisfaction and productivity. Countries, including Japan, Taiwan, Indonesia, South Korea, Zambia and most recently Spain (becoming the first European country to join the initiative), have laws that allow women, who experience severe physical and emotional menstrual symptoms, to take paid menstrual leaves of up to three days.

While these are examples of how human societies evolve to serve the need of the hour, some societies are slow to adapt to these changes. Ours is a prime example of this.

As others continue to progress, Pakistan remains way behind, not just in terms of employee wellness, but also inclusivity, diversity and equity. Currently, Pakistan is ranked as one of the lowest in South Asia and globally for women’s participation in the workforce, with only 20% of women employed in the formal sectors. Moreover, according to the United Nations’ Gender Gap Index Report 2022, we are one of the worst countries in terms of gender inequality, ranking 145/156 for economic participation and opportunity, 135/156 for educational attainment, 143/156 for health and survival, and 95/156 for political empowerment.

You may wonder why, when the rest of the world is progressing, do we remain stagnant?

Well, these conditions were not bred in a vacuum, but have resulted due to several socio-cultural and economic factors. One such factor is our out-dated corporate culture that largely ignores women’s health and wellness, actively keeping women out or making them eventually drop out of the workforce. It can be argued that the 9am to 5pm model is an inherently patriarchal system, designed by men for men.

The female hormone cycle and its incompatibility with the 9am to 5pm model

It is fair to ask why the eight-hour workday model has lasted so long when it is inherently flawed? The simple answer is that it was not designed keeping women and other gender minorities in mind. It has worked for so many years because it suited men who do not have as many domestic, child-care and emotional responsibilities as women do.

However, when women started entering the workforce, this system created more problems than one, limiting them from excelling in the corporate world.

Why?

Apart from the various social, cultural and economic factors, which are often the topic of debate, there are various biological reasons that inhibit the way women work and how they are treated when they suffer. Male and female bodies, as well as hormone cycles are quite dissimilar. Whereby, men have a 24-hour hormone cycle that is highly compatible with the traditional 8-hour workday starting in the morning, women, on the other hand, have a 28-day cycle. Let’s break it down.

According to Dr Allison Devine, Board Certified Ob/Gyn at the Austin Diagnostic Clinic

and Faculty at Texas A&M Medical school, men wake up every morning with testosterone and cortisol levels at their highest. This enables them to be focused, energetic and ready to take on the day. They experience high levels of productivity and efficiency due to these hormones. By afternoon, their testosterone levels drop slightly, putting them in a mood most suitable for social interactions and networking. As the day bleeds into night, testosterone levels dip and with them the productivity and energy also diminishes, ideally putting them in a state of relaxation. So men wake up every morning, work throughout the day, and kick back and relax in the evening, with their hormones assisting them at every stage of their day.

Contrastingly, the female cycle has four phases. The menstrual phase, as the name suggests, is when women menstruate, having low levels of energy, ideal for low effort tasks, such as resting and reflecting. Then comes the follicular phase, wherein, creativity flows, proving suitable for exploring ideas, planning and engaging in creative pursuits. Next is the ovulatory phase, during which testosterone levels are the highest, therefore, making it best suited for socialising and networking. Lastly, there’s the luteal phase, which is the highest productivity period, ideal for performing focused tasks and organisation.

These hormonal phases can act as a useful map to arrange thinking, planning, executing and completing projects. So, instead of planning tasks on a day to day basis, if women were allowed the flexibility to create their own schedule, based on their hormonal phases, they could work more productively.

Marketing Expert and Health Coach extraordinaire Nazish Chagla explained that, “The premenstrual and menstrual phases are the most difficult ones, when progesterone, which is responsible for keeping you calm and composed, is declining rapidly. This brings about a huge shift in mood and productivity. Meanwhile, oestrogen is also not at the highest during this time, making the menstrual phase good for slowing down and resting. The best time to start a new project is the follicular phase because testosterone and oestrogen are peaking, making you more creative and productive. The luteal phase is when you want to go the haul and get difficult tasks done.” Chagla added, “However, there are other things to consider, as well. Since there is blood loss during the menstrual phase, it has an impact on your focus and energy. This does not apply to working out because it is interestingly a good time for exercise and you can have good gains during this time but it is not ideal for working on other tough tasks.”

This gives us sufficient grounds to claim that the 9-to-5 model is not, in fact, the best model for women. Even for those, who may not experience severe, disabling menstrual symptoms that necessitate menstrual leaves, the 9-to-5 might be an obstructive and counter-productive model. Women are equally important economic agents as men and if a work culture that is better suited to their unique biochemistry is incorporated, giving them the freedom to plan their tasks according to their hormone cycles, they can be far more productive and efficient.

The triple shift

Women’s fluctuating biochemistry is not the only factor that makes the 9-to-5 model toxic for them. Beyond biology, there are other socio-cultural constituents that hinder women’s performance when they work strictly between 9am and 5pm. Our society is marred with patriarchal values that often expect women to shoulder the majority of domestic responsibilities in addition to their professional obligations.

A ‘good’ woman is expected to wake up early, prepare breakfast for the entire family, pack lunch boxes, send the kids to school, and then go to work. She is also expected to maintain a clean house, have steaming food ready, and fulfil the emotional needs of her family. If she can juggle all these duties and still hold a job, great. She is applauded. She is cited as an example of women who can do it all, have it all.

But if she can’t, she is often expected to quit her paid employment and devote her life to her primary job as a mother and wife. Meanwhile, men are seen as the breadwinners of the family and encouraged to relax after work hours are complete.

According to Faiza Ali, Associate Professor at LUMS, “the whole argument is that daytime is for work because you can work at your full potential. So you start working in the morning and way into the evening and then rest at night when it gets dark. However, it doesn’t fit well with women’s responsibilities, especially in the context of Pakistan.”

Along with these responsibilities, Ali points out other aspects of our culture that create circumstances that either don’t allow women to work, limit them to select few sectors, or produce substandard quality of work. Poor performance at the office then bolsters gender stereotypes, such as women were not made for this work. Ali also notes that a joint family system often doesn’t favour women working in paid employment that requires them to be away from home from morning to evening, the most important hours of the day.

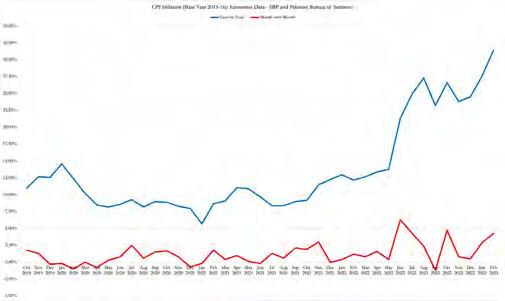

In an economic crisis like the current one, with monthly CPI surging to 31.5% year on year, women will have to enter the workforce because it is becoming increasingly impossible to run a household with one income. However, the multifold burden that falls on women will also not fix itself, placing them at an even greater disadvantage. If a woman does unpaid domestic labour, her work goes unrecognised. But if she works in a corporate office, she is accused of neglecting her family. There is a dire need for more accommodating working hours that can allow women to strike a balance between their personal and professional lives without having to choose one over the other.

Abandoning the chicken and egg problem

Why does Pakistan not have inclusive policies? It is impossible to answer this without opening a pandora’s box.

We can question whether Pakistan’s corporate ecosystem lacks inclusive policies because there aren’t many women in the workforce for there to be a need to assist them? Or is it the other way round and the percentage of women in the workforce is so low because the lack of mechanisms for inclusivity and diversity is industriously keeping them out? There are many different ways to ask this question and they will all bring us to the same chicken and egg problem. And it doesn’t matter whether the workplace is discriminatory against and ignorant of women’s needs by design or accident.

All these questions are rendered bootless when we admit that women have been entering or willing to enter the workforce for quite a while now, yet little is being done to make the workplace more gender inclusive and equitable.

So, the question then is, why have we failed to come up with a solution?

According to Dr Nida Kirmani, Associate Professor of Sociology at LUMS, “It is a combination of ignorance and a simple lack of care. There is a general idea that, if a woman is given a job at all, she is lucky rather than the other way around. Companies are designed with the male employee as the standard, and women are expected to conform to that mould.” So, women are largely ignored when designing HR policies and incorporating inclusive practices.

The Head of Legal at FrieslandCampina Muneeza Iftikar believes that there are two major problems, when it comes to issues concerning diversity in organisations. “First is simple; most organisations have men in senior management positions, and it all boils down to a lack of knowledge regarding issues concerning women. This is not something they are just not willing to do, rather they don’t think about it, so at times it has to do with lack of awareness of the kinds of issues women face.”

Iftikar shared an anecdote from almost a decade ago to elaborate on her assertion. “I remember one of my previous employers wanted to see why they were unable to retain female talent, so they decided to conduct a focus group, where they got different employees, including senior, junior, married, or single and male or female to come together and closely consider different aspects of the business. We were talking about whether we should have a daycare and flexible timings and whatnot.”

“One of the only female engineers on site had joined us and while this discussion was happening, she raised her hand.. She was expecting a baby, while working and living on the site. The site had just one female toilet on the opposite end of the plant and because of the nature of the plant you couldn’t just walk around in it. There used to be a van that took you around because it was a dangerous facility. She told us that she had to spend the whole day waiting for that van for one or two bathroom trips during the workday but because she was pregnant, she required using the loo more often than before. And the issue was that a lot of her time would be spent waiting for the van and then going to the training building, then to the bathroom and then coming back.” Iftikar continued.

“I can never forget the look on the CEO’s face. We spent millions on conducting other diversity initiatives, without realising that our one main female employee doesn’t have access to basic bathroom facilities. So, at times there are problems as simple as this and we miss them because women are not a part of the conversation,” Iftikar concluded.

So, the problem is also having an incorrect approach to incorporating inclusivity.

Iftikar gave the example of the Maternity Act 2020, to elaborate upon her argument that if men continue to make decisions for women, even with positive intentions, the results will never be satisfactory. “It is the most horrifically drafted legislation I’ve ever seen. It states that if an organisation has 10% females, you must have a daycare. Now the problem with this is that our organisation, for example, has a 6% female population, so it’s not mandatory for us to have daycares...” But this is not all. “The other side of the problem is that a lot of the time it depends on how good or bad your relationship with the senior management is. When you have a good relationship with the management, it is easier to highlight the problems that exist, and they do try to work out a solution.”

However, Iftikar also opined that talking about women’s health ‘turns a lot of people off’. “Especially older but also younger gentlemen get a bit uncomfortable and don’t want to discuss it. I once proposed that free sanitary pads should be put in the office bathroom,” she shared but the reluctance of her superiors came in the most absurd form of excuses. “What if the pads get stolen” and “We can’t do it due to budget issues” or “We don’t wanna talk about it, this is some- thing which makes us uncomfortable,” are some of the questions they asked.

Imagine discussing the concept of premenstrual dysphoric disorder with them.

“We have been instructed all our lives that periods are not something that we can discuss openly and as you guys get older you just kind of figure out how to manage on your own,” Iftikhar told Profit. But even if you can somehow grow past the shame that is associated with any discussion around the topic, the reaction is one of men baulking at the thought of providing a solution.

Beyond policies and legislations, there is a pressing need for a mindset shift.

According to Iftikar, one of the most important things that we need to acknowledge, which often goes against women, is their ability to find alternatives on their own. Women stick together, rely on each other and often create spaces for themselves. As wholesome and endearing as this sisterhood is, it relieves the organisation from the obligation to consider women’s issues.

What can we do?

The struggle for work-life balance is an ongoing battle for women around the world, but in Pakistan, it is a fight that is both urgent and complex. As women continue to fight for their rights, experts from different fields have offered their insights to Profit on what needs to be done to achieve a more equitable workplace.

According to Dr Ghazna K Siddiqui, a Consultant Obstetrician Gynaecologist and International Women’s Health and Health Advisor for the Government of Pakistan, “Fixed menstrual leaves can be helpful, but they may lead to positive discrimination. What we can have is flexible working hours and weeks that allow women to plan ahead and arrange their schedule, such that they don’t have as much workload during the days they are menstruating. Moreover, one good thing that came out of the pandemic is remote working, and if the nature of your job allows it, employers should be willing to let you work from home.”

However, Dr Nyla Ansari, an Assistant Professor and Chairperson of the Management Department at IBA, believes that there is no “one-size-fits-all” solution. “Certain jobs require you to be on the ground, so you cannot work from home. Women know when to expect their period, and if they can plan ahead and manage their tasks accordingly, it would not only benefit them, but their employers will also be better prepared.” The need for action goes beyond just individual efforts. Kirmani believes that “we definitely need better laws and policies to ensure that workplaces are gender equitable. This includes protections against discrimination and general family leave policies, which include both maternity and paternity leave. In general, more flexible approaches to employment, which would include options to work from home and daycare facilities, would be more beneficial for women and men.”

The need for change is urgent, and the solution must come from a multifaceted approach. It requires inclusive HR policies, better laws and policies, and flexible working hours to ensure that women have the support they need to achieve a work-life balance. Ali shared that “Dutch women’s economic participation rate is quite high, even though their culture is very home-focused. So, in Scandinavian countries equality is quite common. They came up with the idea of part-time work, and that’s what I think is very important in the context of Pakistan as well.”

A beacon of hope in the war-stricken future

Amidst these myriad challenges, there is hope on the horizon. A handful of local and multinational companies are leading the way in creating a more inclusive work environment, setting an example for others to follow.

Take HBL, for instance. This financial institution is committed to raising its female workforce from 17.7% in 2020 to 20% in the future, with a focus on recruiting women for junior level positions. Moreover, it has introduced the NISA banking account, which aims to increase women’s financial inclusion from 5% to 25%. Shell Pakistan, in collaboration with the National Rural Support Programme, has established a Business Center for Women in Bahawalpur, offering enterprise development sessions designed specif- ically for women. The “She in Shell” programme is dedicated to providing employment opportunities for women who have taken a career break.

On the multinational front, Unilever and P&G are leading the charge in promoting gender equality in their Pakistan divisions. Unilever boasts a management team that is 52% female, and offers 16 weeks’ paid maternity leave as a minimum worldwide, including in Pakistan. P&G’s Gender Equality initiative, under the #WeSeeEqual programme, includes the HOPE programme for women’s skill development and girls’ education, as well as a commitment to mentor 500 women under Million Women Mentors.

A study by Salas-Vallina et al (2020) indicates that there is a positive correlation between happiness at work and how well employees can sell additional products in the banking industry. Another study by Bellet et al (2019) finds similar results. What does this mean? Companies are leaving money at the table, if nothing else, by continuing to ignore their female talent and their wellness. The traditional approach of treating employees as mere machines, disconnected from their own bodies and families, is outdated and detrimental to overall workplace morale. By adopting a more holistic and empathetic approach to employment, companies can create a workplace culture that supports and uplifts all employees, leading to greater job satisfaction, productivity, and ultimately, success. So, departure from the 9-to-5 not only helps women, but has far-reaching benefits for the overall economy. n