10 minute read

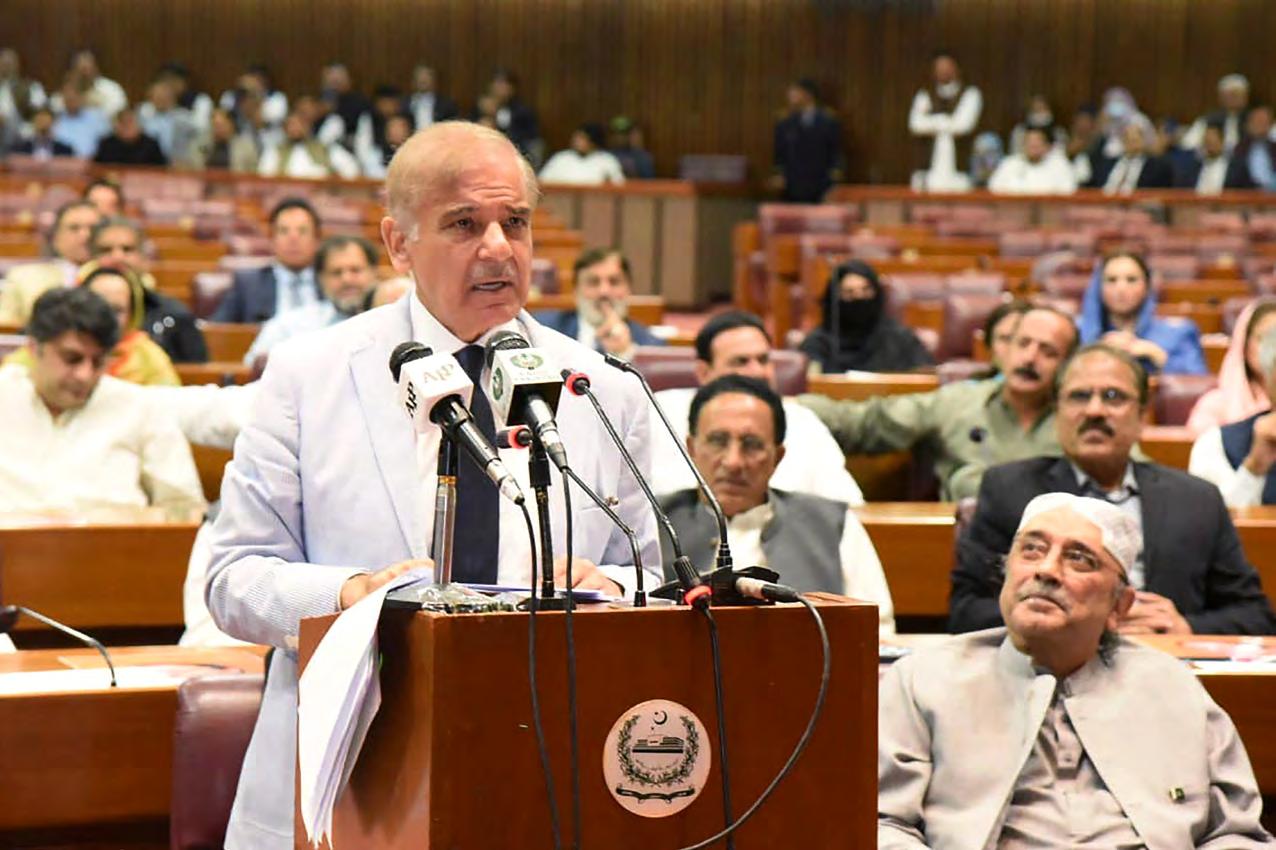

Can Shehbaz Sharif stabilize a faltering economy? Can Imran Khan make a comeback?

The numbers are coming in and they don’t look pretty. Last Thursday the new government of Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif was informed where the prices of essential fuels – petrol, diesel, kerosene – will rise to if the price caps announced by the former Prime Minister were to be removed in one go (see table). The next day the official twitter account of PML(N) that deals with economic matters announced that the fuel price caps are here to stay for the time being.

Advertisement

Minutes later finance minister designate, Miftah Ismael, tweeted that he has just had a meeting with the World Bank Country Director and the IMF’s Resident Representative in Islamabad, describing the meeting as a “courtesy call” that they made on him.

The moment revealed the sharp trade-

offs the new government is facing. The next day Miftah shared a few numbers via his twitter handle, saying the cost of the fuel subsidies “is more than the cost of running the entire civilian federal government plus the entire BISP/Ehsaas programme.”

No wonder the meeting with the IMF and World Bank chiefs took place on the same day as the decision to retain these subsidies (for the time being) was made. The first order of priority for the new government is to revive the IMF program and arrest the decline of the foreign exchange reserves. This cannot happen with the subsidies in place.

Earlier in the week the State Bank showed some numbers of its own to Pakistan’s foreign creditors in the bond markets. In an investor presentation they showed the current account deficit projected to reach $17 billion by end of FY22, up from their earlier projection of $13 billion presented back in February. For next year they showed gross external requirements reaching $46 billion in the next five quarters (April 2022 till June 2023).

The last staff report released by the IMF in February 2022 showed next year’s gross external financing requirements at $35 billion. Even allowing for the fact that the $46bn figure refers to five quarters instead of four, it is hard to miss the massive increase in the country’s requirements for external financing to meet its debt obligations in the months ahead. Of

And even the $46bn projection is built on optimistic assumptions. For example, it assumes that the CAD will be $10bn in FY23, and the bulk of the available financing the State Bank showed with which it intends to meet this requirement will come from multilateral financing as well as oil facilities coupled with rollovers from bilateral creditors. None of this is happening without an active Fund program in place.

So revival of the fund program is a critical objective and its prerequisites are weighing heavily upon a government composed of an unwieldy coalition facing formidable opposition

from Imran Khan whose people are threatening full fledged “civil unrest” in the days ahead. In this context, hiking the price of petrol by Rs21 and the price of diesel by Rs51 (especially at the start of wheat harvesting season when the demand for diesel spikes, and hikes in its price will inevitably lead to higher flour prices) is suicidal.

The fuel price hikes will impart a powerful inflationary pulse into the economy and cascade through the price level across the board. With rising CPI will come pressure to raise interest rates, which in turn will slow the economy, causing whiplash across the business community and turning the clock back to the months that followed the July 2019 accession to the Fund program that the country is struggling to complete today. And the fallout will fall squarely on the current government.

Can Shehbaz Sharif walk this road? Short answer is he has no choice. He can delay the decision, but delay has its own cost. He can stagger out the inevitable, do it over a period of time. Or he can seek help from “friendly governments” like in the past. This would mean approaching Saudi Arabia, China and the UAE for a temporary shot in the arm while he prepares to walk down this road. None of these options are easy.

Can Imran Khan mount a comeback?

It is difficult to discern what exactly Khan’s strategy is through all this. He is clearly not interested in playing it out within the confines of the parliamentary system. The resignations he has ordered his party MNAs to submit show he is looking for an exit from the system to be able to attack it from the outside. The purpose of these attacks will be to paralyse the government and jam all decision making with the ultimate aim of forcing them to hold early elections. But how to graduate out of rallies and speeches towards paralyzing attacks? Next level up from rallies and speeches is the politics of agitation. But the problem with agitation is it requires the political party to be linked up with organized interests in society. Crowds that attend weekend rallies are not enough. Agitation would mean Khan issuing a strike call today which is observed around the country the next day. We are far from that right now. For agitation to work, he will need to establish contact with the myriad organized interest in society like the trader associations or the bar associations or port workers unions or transporter associations. It will work if he can cripple the conduct of day to day like – urban mass transit grinds to a halt, shops are shuttered, lawyers boycott the courts and stall litigation, port workers strike and cargo piles up on the ports while ships wait in outer anchorage and business is hit badly. This is what it took the last time we saw agitation politics in our country in the PNA movement of 1977. So what organized interests in society can Khan link up with? The traders are very reluctant to shutter shops, especially on

ideological appeals. The bars associations are almost universally opposed to him after the Justice Qazi Faez Isa case and the unconstitutional steps he took to prevent the vote of no confidence from being held. The labour unions are not what they used be back in the 1970s.

The Peshawar jalsa may have provided a clue. In that rally he escalated escalated his attacks on the government to go beyond accusing them of being thieves and traitors. He accused them of blasphemy as well.

One cunning trick he used in Peshawar was to name Geert Wilders specifically during his speech, the Dutch lawmaker famous for his Islamophobia. This prompted a response from Wilders via his twitter account in which he referred to Khan as a “hate monger” and took the opportunity to make another blasphemous remark. The next day Saad Rizvi, the young head of the Tehreek Labbaik Pakistan (TLP) issued a fatwa during his Friday sermon calling for the death of Wilders.

TLP followers unleashed a barrage of threatening tweets against Wilders, tagging him with pictures of knives and guns along with words like “we are coming to get you”. Wilders was only too happy to retweet all this to his own followers. This exchange continued for days. As of writing this the Karachi jalsa has not begun so it is not known whether Khan intends to escalate this further by stoking these kinds of exchanges between Pakistani social media users and European lawmakers.

But it is possible part of his strategy includes escalating this to a point where he can advance a demand that the new government of Shehbaz Sharif should condemn these lawmakers and possibly demand the eviction of European diplomats from Pakistan, failing which he can argue he will lead a long march to lay siege to Islamabad, aided perhaps by the TLP, to force the government to take action against blasphemers abroad and their diplomatic missions here. As such, he would take a page out of the TLP’s book last year.

It is too early to say, at the time of writing, whether this is what Khan intends, but it will become clear within days. If in the Karachi jalsa there is further escalation of the blasphemy rhetoric and more mention of European lawmakers by name, it will be a clear indication that Khan is trying to incite the TLP and link up with them.

If Khan is unable to graduate from rallies and speeches to active agitation, his chances of making a comeback diminish with time. At the moment he has 94 elected members in the assembly who have submitted their resignations (the rest are reserves seats and are merely extras in the drama of politics) and 32 who have so far not resigned. If these resignations go through it will be a blow to the assemblies, but it will not necessarily force their dissolution. We will have the largest number of bye-elections we have ever seen, but nothing more. To top it off, the costs of these rallies is now beginning to weigh on him, prompting an appeal for donations from overseas Pakistanis to be able to carry on his campaign.

Next up the PTI will probably have to boycott the bye-elections, forcing his MNAs to decide if they want to remain with Khan or seek a ticket from another party to seek their reentry into the system. Many of these “electables” pay a steep price for remaining outside power for very long because contenders within their own constituencies are only too glad to step in and fill the void they have left by opting out.

By opting out of the system altogether Khan has taken on a much bigger challenge to bring about his own comeback. He has to either escalate to agitation politics, or sustain the momentum of rallies and speeches for many months.

Either way, the choices facing him are no less stark than the ones his opponent – Shehbaz Sharif – is facing. n

The wild card: Imran Khan’s popularity

By far the biggest wild card at play in all this is Khan’s personal popularity. He is drawing far larger crowds than any of his predecessors did following their disqualification, and his rallies are charged and the crowds are organically driven. These are not rent-a-crowd rallies.

But how far does personal popularity drive electoral outcomes? And how new is it? “Over time all the polls I have seen in public and non public domains show that Khan has been the most popular leader for the past four years at least” says Azeema Cheema, Director Verso Consulting a former elections analyst who has lot of experience working with political opinion polls. “In 2012 he was genuinely the most popular leader in the country as well” she says, “but after that his popularity declined when he started bringing traditional electable politicians into the party. In the post 2013 election he was competing for popularity with Nawaz Sharif, Shehbaz Sharif and Raheel Sharif as well, who was a very popular army chief. The thing to note is some of these figures are very polarizing. Nawaz and Imran were both very polarizing, but not Shehbaz. Since 2018 Khan has managed to retain his position as the most popular leader in the country.”

The PTI is also armed with a formidable social media machine. Early morning on April 15 their official account tweeted some metrics for a hashtag that has been trending for many days now showing 30 million tweets and more than 80 million engagements. “The people of Pakistan have completely rejected the imported government!” they said.

But social media engagements and personal popularity don’t necessarily mean electoral strength. Consider, for example, that there are 3.4 million twitter users in Pakistan whereas 55 million voters participated in the 2018 general election. Electoral communication is a far more complex task than televised speeches and social media trends. Translating personal popularity into electoral outcomes involves being able to communicate with local influencers in the constituencies – the so-called dharra and biraderi networks and their leadership. Social media influencers can help drive engagements and reach, but they cannot deliver votes where it counts.

So Khan’s challenge is to grow his own popularity and brand, but eventually he will have to swivel out of televised speeches and social media projection and learn to communicate with voters on the ground. Being outside the system always makes this harder, because one language voters understand clearly is tangible service delivery. Without that lever, translating his personal popularity into votes for his party will be Khan’s big challenge.