14 minute read

NEWS CLIPS

Sen. John Hickenlooper answers questions from electric co-op directors, managers and staff members during their visit to Washington, D.C.

CO-OPS VISIT WASHINGTON, D.C.

Directors, managers and staff members for Colorado electric co-ops joined hundreds of other co-op representatives from across the country in Washington, D.C., May 2–3 for the annual co-op legislative fly-in.

They spent a day learning about federal issues that affect electric co-ops and another day meeting with Colorado Sen. John Hickenlooper (D) and staff from the office of Sen. Michael Bennet (D), as Sen. Bennet had tested positive for COVID-19. The co-ops also met with staff members from all of Colorado’s U.S. representatives. There was also a discussion with a representative of the Department of Energy on funding for projects through the recent Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

Co-op Magazine Plants Trees

Colorado Country Life magazine supports planting trees each month and has done so since 2018. A total of 14,395 trees have been planted in reforestation projects in North Dakota and California to replace the paper used to print the magazine.

For 70 years, Colorado’s electric co-ops have sent this magazine to you because it is the most effective and economical way to share information on your local electric co-op. The magazine, which is read by more than 80% of the co-op consumer-members receiving it, provides you, as a voting member of your co-op, with information about your co-op’s services, director elections, member meetings, and staff and management decisions.

And, through a verified program called PrintReleaf, trees continue to be planted.

Colorado Co-ops Again

Bring Light to Small Guatemalan Rural Village

The lights will come on in mid-August in La Montanita de la Virgen, Guatemala, thanks to a team of 16 lineworkers, including four from Colorado electric co-ops.

The team, which leaves the United States August 1, will build a 19.9 kilovolt single-phase distribution line on poles provided and set by the villagers. That line will bring electricity to 72 homes, a school, a church and a health center.

More than 250 people live in this small village about three hours east of Guatemala City. It sits at an elevation of about 4,500 feet with mostly pine trees, banana trees and pineapples growing in the area. About 80 students attend the local elementary school.

This is the third project in Guatemala for Colorado’s electric co-ops. Watch for information on how to help send backpacks and other supplies to the students in the village.

NW Colorado Rancher

Wins Conservation Award

The conservation practices of electric co-op consumer-members Keith and Shelly Pankey and their children on their ranch in Moffat and Routt counties earned them the annual Colorado Leopold Conservation Award. The award is sponsored, in part, by Tri-State Generation and Transmission Association, the power supplier for 17 of the state’s 22 electric co-ops.

The award is given in honor of renowned conservationist Aldo Leopold and recognizes ranchers, farmers and forestland owners who inspire others with their voluntary conservation efforts on private, working lands.

The Pankey family, who raises beef cattle, has always done right by their land. That was tested when a wildfire burned nearly half of their ranch in 2018. The family then cleaned their ponds and reseeded native grasses on 900 acres. They also replaced wind-powered well pumps with solar pumps, added new water storage tanks and miles of natural flow pipelines to expand the number of watering stations and improve the ability to properly graze cattle while also creating wildlife habitat.

The family’s commitment to conservation is an inspiration.

Co-ops Support Energy Science

Colorado’s electric cooperatives once again sponsored the Colorado EnergyWise Awards at the annual Colorado Science & Engineering Fair in Fort Collins April 7-8.

Judge Stuart Travis, a board member from Y-W Electric in Akron who is also on the CREA board, judged the energy projects at the fair. He selected the top energy project in both the senior and junior divisions as well as a runner-up in each division.

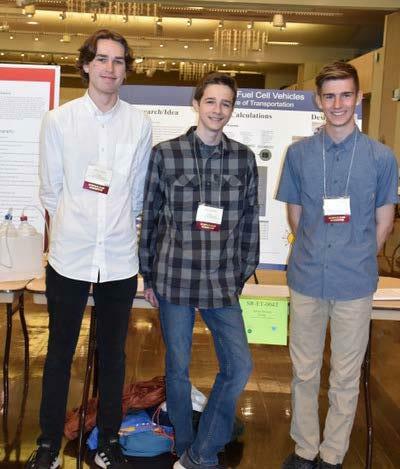

This year’s top winner in the senior division was a project titled “Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicle/Station” by Centaurus High School seniors Alec Mallinger, Oliver Schmitz and Davis Cutforth of Lafayette. Second place went to Sargent High School senior Chinmay Jayanty of Monte Vista for his project on “Reversing Climate Change with Direct Air Capture.”

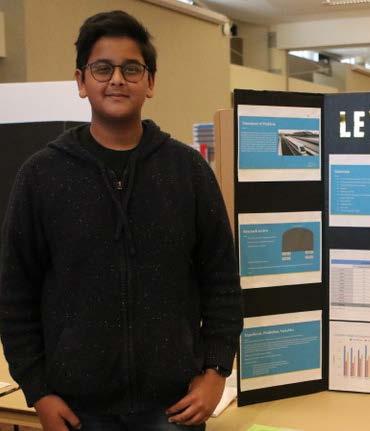

The top winner in the junior division was a project on “Magnetic Levitation” by 8th grader Saatwik Das of Peak to Peak Charter School in Lafayette. Second place went to Wiggins Middle School 7th grader Skyelyn Lefever for her project on “Homemade Batteries.”

The electric co-ops awarded $175 to the first-place winners and $75 to the runners up.

1st place - 12th grade - Alec Mallinger, Oliver Schmitz and Davis Cutforth all of Centaurus High School in Lafayette.

1st place - 8th grade - Saatwik Das of Peak to Peak Charter School in Lafayette. 2nd place - 12th grade - Chinmay Jayanty of Sargent High School in Monte Vista.

1st place - 7th grade - Skyelyn Lefever of Wiggins Middle School in Wiggins.

The Steps to Restoring Power

When a major outage occurs, our crews restore service to the greatest number of people in the shortest time possible – until everyone has power.

1. High-Voltage

Transmission Lines

These lines carry large amounts of electricity. They rarely fail but must be repaired first.

2. Distribution

Substations

Crews inspect substations, which can serve hundreds or thousands of people.

3. Main Distribution

Lines

Main lines serve essential facilities like hospitals and larger communities.

4. Individual Homes and Businesses

After main line repairs are complete, we repair lines that serve individual homes and businesses.

CAVES AND CAVERNS

NATURAL WONDERS BENEATH OUR FEET

BY MIKE COPPOCK

Exploring the southern flank of the White River Plateau on Colorado’s Western Slope, caving enthusiasts Richard Rhinehart and Rob McFarland discovered an unknown cave now known as the Witches’ Pantry Cave.

It wasn’t the first cave they discovered together and it probably won’t be the last. Colorado is rich in caves. No one knows exactly how many there are.

Some estimate there are 600, while others say it is far less. In 1970, 265 caves were listed in Colorado. But today, with continual discoveries by cavers, Rhinehart puts the number closer to 1,000.

The day they were on the White River Plateau and found the open pit that led into a cave below the surface, Rhinehart and McFarland were exploring an area marked for development in the expansion of a limestone quarry near Glenwood Springs. The two men wanted to see if there were any significant caves in the area that might be at risk by such expansion.

Excited when they found the cave, the two brought in a group to help them explore further into the cavern. They squeezed through a low passageway into a crevice that descended deeper. Lowering themselves down the crevice, they found a lower chamber that seemed to go further back into the plateau.

Since this initial exploration of Witches’ Pantry Cave, the group has worked with the Bureau of Land Management on future access and exploration. Plans are in the works to send down a paleontologist to examine bones of animals that have fallen to their death from the pit entrance, many of which appear to be domestic sheep.

Rhinehart and McFarland also hope to use electrical resistivity to see if there are large voids around the cavern. The technique has been used throughout the West for identifying known and unknown cave passages and chambers.

It was another day in 1984 when they discovered Silent Splendor within the Cave of the Winds at Manitou Springs. The room held numerous rare crystalline speleothems, including helictites that appeared to defy the laws of gravity by growing in strange directions and not being forced down by gravity like many cave formations are.

Caves offer all kinds of natural wonders. Coloradans revel in the beauty of the Centennial state in all its various forms: the hues of the Rocky Mountains, the stark landscapes of the Western Slope and the endless grasslands of the eastern plains. Yet, most miss the natural wonders beneath our feet.

Caves pepper Colorado

“Given that there are caves in limestone, gypsum, granite, sandstone, quartzite and even claystone, there are most likely more than a thousand caves within the state at this time,” Rhinehart claims.

Caves pepper Colorado with their wonders primarily due to limestone. Once where towering mountains are now, there was a sea, its floor becoming the source for the limestone. Uplift sent parts of the ancient seabed — and thus a large limestone layer — up along the slopes of the Rockies where snow and rain penetrated fissures in the limestone, sculpting caverns through the eons.

Some of these caverns transformed into underground cathedrals with massive spiral columns reaching from the floor to ceiling. Standing on the cave’s floor, a caver with flashlight in hand can see the wonders nature and erosion created.

Other caves are little more than cracks in rock with a stream of water snaking through narrow formations downward into the dark. Those who enjoy the sport of caving, also called spelunking, feel their way through tight passages with a mountain of rock above them and no quick and easy escape to the surface as they follow a water stream to wherever it takes them in the dark.

There are roadblocks in obtaining an exact count on the number of caves in the state.

“That information is unavailable due to natural resources’ sensitivities within and around the caves,” says Donna Nemeth, media spokesperson for the National Forest Service.

But with cavers such as Rhinehart and McFarland constantly making new discoveries, we are learning about more and more caves.

Popular Colorado caves

Discovered in 1968, Colorado’s longest cave, the Groaning Cave in White River National Forest, is a system of domes, underground cathedrals and tight passages that go back into the Rocky Mountains for 15 surveyed miles so far. It may be longer.

The Fixin’ To Die Cave near Glenwood Canyon is the state’s second longest at 4 miles. Colorado’s deepest cave is Spanish Cave near Westcliffe, which drops downward for 741 feet below the surface. Next in depth is Hurricane Cave in Garfield County at 553 feet.

But are the state’s caves and caving that strong an attraction?

“We essentially get inquiries about Colorado’s commercial caves like Cave of the Winds and Glenwood Caverns,” said Carly Holbrook of Handlebar Public Relations, which handles inquiries for Colorado Tourism. “I have never encountered anyone querying about caves and caving, though.”

WONDERS BENEATH OUR FEET

KARST TOPOGRAPHY is a landscape that is characterized by numerous caves, sinkholes, fissures and underground streams. Karst topography usually forms in regions of plentiful rainfall where bedrock consists of carbonate-rich rock, such as limestone, gypsum or dolomite, that is easily dissolved. Surface streams are usually absent from karst topography. DISSOLVED JOINT RIVER

STREAM DISAPPEARS

CAVE LIMESTONE

CRACKS

CORRIDOR

CAVERN

KARST SPRING SUBTERRANEAN RIVER STALACTITE STALAGMITE UNDERGROUND LAKE

LIMESTONE COLUMN FLOWSTONE

Caving enthusiasts

Mostly going unnoticed, an active group of caving enthusiasts has been exploring caves going back to the 1950s, if not longer. Members even have a publication, Rocky Mountain Caving, which first appeared in 1984. Today, Colorado has five clubs or grottos, a term used to describe a local chapter of cavers in an area.

The Colorado Grotto is centered in Denver while the Front Range Grotto is for cavers in the Boulder-Northern Denver suburbs. The Western Slope Grotto is centered in Glenwood Springs; the Northern Colorado Grotto in the Fort Collins area; and the Southern Colorado Mountains Grotto is in the Colorado Springs area.

Why would people squeeze and struggle through rock passages in the dark, literally under a mountain of rock?

It can be a dangerous sport. Cavers — and others who venture underground — can face flooded or partially flooded caves, cave ins and injuries such as a broken leg while deep in a crevasse.

For that reason, many cavers are trained to assist if an accident occurs underground or if a visitor is injured or turns up missing.

But as with any endeavor, the excitement and adventure of caving usually outweighs the dangers.

“Cavers basically venture underground for recreation and the sport of exploration of the unknown, but many have interests in various disciplines,” Rhinehart said. “This includes science, biology, microbiology, hydrology, mineralogy and geology.”

Rhinehart noted some cavers had spent years walking over limestone-rich sections of the state in search of caves without finding any. Other cavers work cave entrances that have collapsed or become plugged with sediment, trying to reopen them to gain entry.

Nearly all cavers have an interest in protecting and preserving the caves and cave features as well as enjoying a unique sport.

“In almost every instance, cavers generally do not report new discoveries to help protect the cave from abuse from others, either accidental or intentional,” Rhinehart said.

Cavers’ activities and word of mouth, however, have at least led to the public’s awareness of some of the state’s caves other than the three commercial caves: the Cave of the Winds, Glenwood Caverns (also known as the Fairy Caves) and the Yampah Vaper Cave.

The non-caving public has either visited or knows about the Ice Caves near Aspen; the narrow Fault Cave outside of Golden; the Fulford Cave outside of Eagle with its bats and 80-foot-high underground ceilings in some chambers; and the Spring Cave near Meeker, which has a subterranean river running through it and, like Fulford, serves as a winter hibernation chamber for bats.

Protecting caves

Continuous lobbying by the cavers’ group and by the National Forest Service led to the Colorado Cave Protection Act signed in 2004 by Governor Bill Owens. The law makes it a misdemeanor to damage or deface a cave.

A White River National Forest ranger discovered someone had sprayed graffiti on the walls of Spring Cave, and both Glenwood Caverns and Cave of the Winds suffered from souvenir hunters and vandalism through the first half of the 20th century.

“History tells us that several chambers along the cave’s popular commercial route once were as well-decorated as Silent Splendor, but abuse by visitors since 1881 destroyed these beautiful places forever,” Rhinehart said of vandalism at Cave of the Winds prior to the passage of the 2004 law.

Vandalism is not the only concern that may cause limited access to caves or their closure to the public. Recently, biologists have been monitoring the spread of white-nose syndrome within Colorado’s bat

— Richard Rhinehart

population, which can prove deadly, and its spread by certain fungi. The fungi can be tracked into caves by way of cavers’ clothing and equipment. Finally, biologists simply want bats not to be disturbed during their winter hibernation.

“All known cave hibernacula [where creatures seek refuge] are closed during the winter hibernation period,” Nemeth said. “In Colorado, this includes caves on the White River National Forest. The White River National Forest also has caves that are closed year-round to minimize disturbance to bats.”

Nemeth underscored that caves that are not closed year-round do have a registration system and decontamination guidelines which must be signed and followed by those entering the caverns. (whitenosesyndrome.org)

So, when thinking about exploring Colorado’s rich abundance of natural wonders, remember that the natural world extends beneath our feet into the caverns and crevasses of Colorado.

INTERESTED IN REGISTERING TO EXPLORE A CAVE?

Registration involves submitting basic personal information online such as name, email address and ZIP code as well as the date of the trip, cave name, national forest and number of participants in the party. After the information provided is processed, an approved registration form is provided to the person making the request. The requesting party is required to print and sign a copy of the approved registration form with each participant signing the form.

The registration request is then reviewed and processed by the National Forest Service. The process usually takes two to three business days. Questions about the registration process can be emailed to SM.FS.r2wns@usda.gov. The Rocky Mountain Region Cave Access registration form can be obtained through the Rocky Mountain Region’s public website: tinyurl.com/2p8ztydh. For most caves in national forests and grasslands, complete and save the cave registration form and email it as an attachment to: SM.FS.r2wns@usda.gov. Written requests for the cave access registration form may be submitted to the Rocky Mountain Region at USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region, 1617 Cole Blvd, Building 17, Lakewood, CO 80401, Attention: Cave Registration Request. There is no registration fee.