6 minute read

NATURE IN WINTER

At home in a snow-clad landscape

BY SANDRA STRIEBY

Winter brings new ways to understand the natural world. Plants and animals use a variety of approaches to survive the season, some of which reveal themselves when we spend time outside. Observing nature in winter can give us a richer understanding of the world in which we live and how other beings have adapted to it.

ANIMALS ON THE MOVE

Animal tracks in snow are one of the delights of the winter landscape, showing travel patterns and providing clues to behavior and lifestyle. From the delicate tracings of mice and kangaroo rats to the deeply entrenched trails created by deer, tracks give us insights into the lives of animals we may never see.

Tiny mammal tracks often radiate from the base of a shrub—the animals’ entry point into the world beneath the snow, where they find food, shelter, and some safety from predators. Living under the snow isn’t entirely secure— owls and coyotes may plunge through to reach animals below, and ermine will use the same openings as the mice and other small creatures to enter the hidden dwellings.

Coyotes leave tracks much like those of domesticated dogs, with subtle differences that reveal the animals’ wild nature. Coyotes are working animals, unlikely to frolic as pets do. They may meander as they seek prey, but generally their paths are purposeful. And, because they are on their feet much more than domestic dogs, coyotes are fit. Their tracks are generally compact ovals, whereas less-active dogs often leave behind imprints of splayed toes and long claws.

Quail spend a lot of time on the ground, often in large groups that create well-defined pathways as they trek between sheltered food sources. Ravens and crows may reveal their passage by leaving marks like those of a calligrapher’s brush where their wings have swept the snow. And grouse leave some of the most dramatic records of their presence, plunging into the snow for a night’s shelter and then bursting out in the morning, leaving behind an imprint and a heap of droppings that look like stove pellets.

Often tracks are more visible than their makers. While many of us may never spot a bobcat, cougar, ermine, or moose, we may be fortunate enough to see where they’ve been and know that they are present in the world around us. To identify tracks, take a look at the Methow Naturalist’s guide to mammal tracks (https://tinyurl.com/6s8y29cw). Field guides will help you learn more about the animals and their behavior.

CHILLED AND STILLED

Not all animals are out and about in the winter. Some conserve energy by hibernating until warmer temperatures and reliable food and water supplies return.

Bears are perhaps the best-known hibernators, sleeping (lightly) through the winter and living on fat stored under their thick fur coats. Light sleep allows them to respond to danger if they’re threatened, and heavy pelts and substantial body mass help them retain heat. Because they are metabolizing fat, bears produce waste while they hibernate, but rather than excreting it, they recycle the nutrients to maintain their muscles and organs.

Many species of bats hibernate, alternating between periods of torpor and limited activity while they await the return of flying insects. In torpor, a bat’s heart rate, respiration rate, and temperature drop, reducing its energy needs and allowing it to tolerate the cold. Hibernating bats have very specific temperature and humidity requirements, and most congregate in places like caves, crevices, and other dark sheltered spots that meet their needs.

Mourning Cloaks are among a handful of butterflies that overwinter as adults. Chemicals in their blood — sometimes called “insect antifreeze”— keep them from freezing during the long, cold season. The mature butterflies hibernate in dark, sheltered crevices and emerge in early spring when sap, their favored food, begins to flow. Dark-colored wings allow them to soak up heat on cool days as they prepare to mate and lay the eggs that will start a new generation.

Frogs use several strategies to survive the winter. Some freeze solid and may appear dead as their hearts stop beating and they do not breathe. But naturally-produced glucose protects their cells from cold damage, and they are able to revive when temperatures rise, and greet us in early spring as they begin calling for mates.

SHOULD I STAY OR SHOULD I GO?

Some birds avoid the rigors of winter by flying south, some adapt and stay put, and others come to the Methow to escape even colder climes. While colorful songbirds depart once they’ve raised their young, many species are here yearround — owls and woodpeckers; chickadees, juncos, nuthatches, and finches; ravens, magpies, eagles, and hawks all remain and bring life, color, and movement to the winter landscape. From the far north come siskins, crossbills, and redpolls.

Photo by Ashley Lodato

PLANT ADAPTATIONS

Ponderosa pines, Douglas firs, and other conifers stand out in the winter landscape with their green needles and textured bark highlighted by snow. Conifers have evolved a set of adaptations to survive and thrive during cold, snowy winters. Their generally conical shape helps them shed snow, and inclines the branches to bend, rather than break, when snow does accumulate. That same shape, coupled with a generally open structure, makes it easier for all parts of

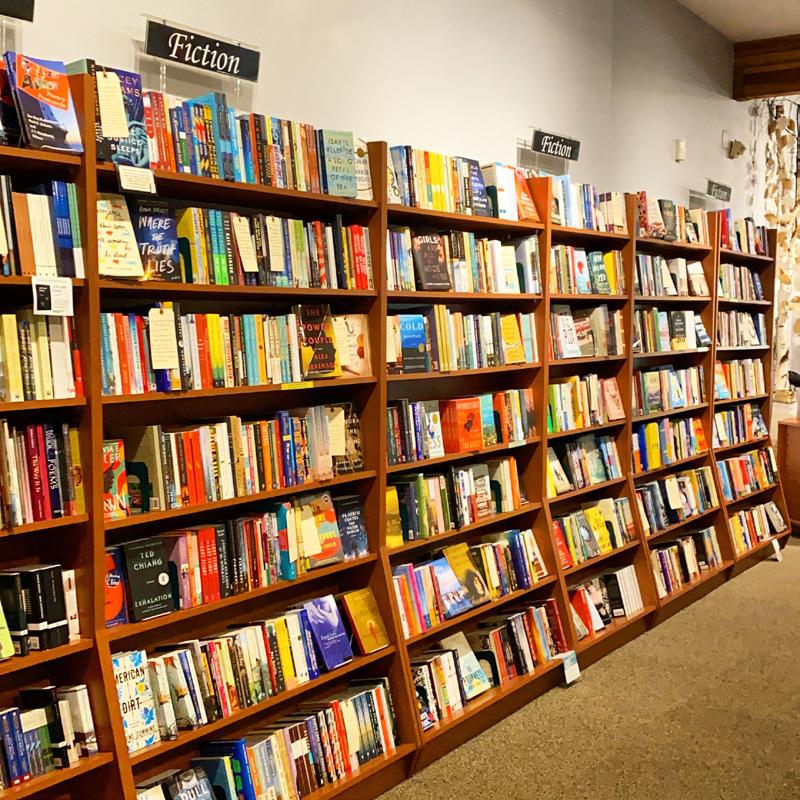

Hand selected books, puzzles, stationary, games, art supplies, and toys.

Our website has up to date inventory Order online!

www.TrailsEndBookstore.com

Contact Us At Locally owned and operated

Methow Valley‘s Independent Bookstore since 1991

241 Riverside Ave|Winthrop, Washington|PO Box 15 509.996.2345|info@trailsendbookstore.com

the tree to catch scarce sunlight.

Catching winter sun is one of the tree’s payoffs for retaining its needles all year long. Another is being able to use the same needles for several years, rather than investing energy in a new crop each spring.

The downside of being green in winter is susceptibility to dehydration, storm damage, and browsing. To counter those threats, conifers protect their needles with a waxy cuticle that retains moisture, toughens the leaves, and makes them less palatable to hungry animals. Terpenes, the chemicals that give conifers their aroma, also help deter plant predators. Even the shape of the needles helps the plants conserve moisture; water-carrying vessels are buried deep inside, while photosynthetic cells crowd the surface.

In contrast, deciduous plants spread their limbs wide and create broad flat short-lived leaves that capture the summer sun and then fall in advance of the onslaught of winter. Some of those plants remain eye-catching throughout the cold season, though.

Stems may be colored — willow twigs are bright yellow, dogwood red, and serviceberry purplish-pink. Berries of certain species, such as mountain ash and rose, remain on the plants, providing spots of color and food for birds.

AWAKENING

Even in the depths of winter, the world is preparing for spring. great horned owls mate as early as January, and their calls — the higher-pitched male voice often followed by his mate’s lower-pitched response — carry long distances in the cold air. Alders bloom in February, sending out long dangling male and female catkins to catch the breeze. Wind-pollinated, they benefit from blooming on leafless branches, while pollen can move easily between the flowers. Chipmunks will emerge in the same month, and in very warm spots the first wildflowers may appear. Coyotes are preparing to den, and a spot of blood on the snow late in winter may show where a female in estrus has passed. The wheel of the year keeps turning, carrying winter’s survivors with it.

Photo by Shelley Smith Jones

A moose shows up on a groomed ski trail.

Experience Mazama in the Winter.