ARCHITECTURE

The Church of St Chad Paul Waddington takes a look at the Manchester Oratory

O

f all the English counties, Lancashire was perhaps the one where Catholicism persisted most strongly during the Penal Times that followed the English Reformation. As was the case throughout England, influential Lancastrian families, usually wealthier landowning ones living in rural areas, played the leading role in maintaining the Catholic faith. After the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829 Catholic churches sprang up around the estates of many of these families. However, in the newly industrialised towns, it was generally left to the incoming working people to fund church building. The church of St Chad in Manchester is an example of such a church. Manchester’s industrial base expanded very quickly due to its position on the navigable River Irwell, and later the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. With this expansion came a huge increase in the Catholic population, greatly boosted by immigration from Ireland. A large number of churches was required. The first Catholic chapel to be built in Manchester opened in 1774, and was dedicated to St Chad. It was a very modest building hidden from view in a back street. Often referred to as the Rook Street Chapel, it was illegal at the time of building. Catholic chapels were banned until the passing of the Second Catholic Relief Act in 1791, and then permitted only if they had no steeples or bells. We can only presume that the authorities in Manchester took a relaxed view of this particular penal law. Other chapels St Chad’s Chapel served a wide area including Bolton, Rochdale, Trafford, Glossop, Stockport and Macclesfield. Several other chapels were built in and around Manchester in the following years to serve an ever-increasing Catholic population. These including St Mary’s in Mulberry Street. In 1835, the roof of the Mulberry Street chapel collapsed, and the 23-year-old Matthew Ellison Hadfield was engaged to design

20

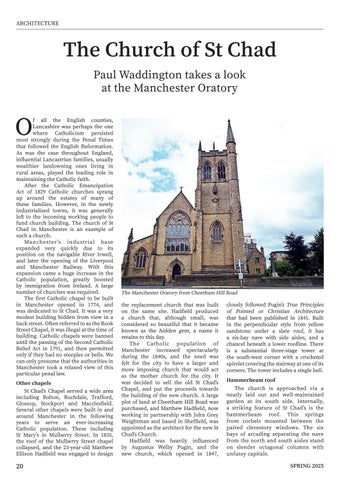

The Manchester Oratory from Cheetham Hill Road

the replacement church that was built on the same site. Hadfield produced a church that, although small, was considered so beautiful that it became known as the hidden gem, a name it retains to this day. The Catholic population of Manchester increased spectacularly during the 1840s, and the need was felt for the city to have a larger and more imposing church that would act as the mother church for the city. It was decided to sell the old St Chad’s Chapel, and put the proceeds towards the building of the new church. A large plot of land at Cheetham Hill Road was purchased, and Matthew Hadfield, now working in partnership with John Grey Weightman and based in Sheffield, was appointed as the architect for the new St Chad’s Church. Hadfield was heavily influenced by Augustus Welby Pugin, and the new church, which opened in 1847,

closely followed Pugin’s True Principles of Pointed or Christian Architecture that had been published in 1841. Built in the perpendicular style from yellow sandstone under a slate roof, it has a six-bay nave with side aisles, and a chancel beneath a lower roofline. There is a substantial three-stage tower at the south-west corner with a crocketed spirelet covering the stairway at one of its corners. The tower includes a single bell. Hammerbeam roof The church is approached via a neatly laid out and well-maintained garden at its south side. Internally, a striking feature of St Chad’s is the hammerbeam roof. This springs from corbels mounted between the paired clerestory windows. The six bays of arcading separating the nave from the north and south aisles stand on slender octagonal columns with unfussy capitals.

SPRING 2025