Bus Stop Safety Improvement Plan

4.2 Bicycle and Pedestrian Solutions While not universally applied, in general, travel for people walking in urban areas has long tended to be accommodated with features like sidewalks, crosswalks, dedicated signals, and curb extensions. The suggested pedestrian treatments in this section address a wide variety of issues identified within Omnitrans’ service area to enhance connectivity, safety, and access to transit stops. Pedestrian improvements help to ensure equitable multi-modal transportation because they serve populations that may not be able to afford a bicycle or likely to ride a bicycle, and instead rely on transit and walking. Newer innovations like pedestrian scrambles, modified signal timing, flashing beacons, and other pedestrian improvements are described in this chapter in addition to standard pedestrian treatments. An increased focus on providing safer, less stressful bicycle travel has occurred more recently across the United States, with significant transformation in the state of practice for bicycle travel over the last decade. Much of this may be attributed to bicycling’s changing role in the overall transportation system. No longer viewed as an “alternative” mode, it is increasingly considered as legitimate transportation that should be actively promoted as a means of achieving community environmental, social, and economic goals. While connectivity and convenience remain essential bicycle travel quality indicators, recent research indicates the increased acceptance and practice of daily bicycling will require “low-stress” bicycle routes, which are typically understood to be those that provide bicyclists with separation from high volume and high-speed vehicular traffic and mixing cyclists with traffic only on low volume, low speed roadways. The bicycle improvements in this chapter ensure more convenient, more comfortable, and safer access to and from transit stops.

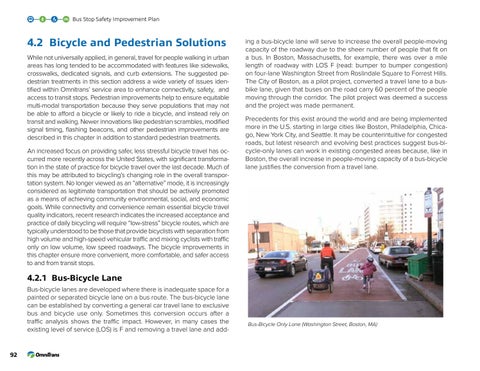

ing a bus-bicycle lane will serve to increase the overall people-moving capacity of the roadway due to the sheer number of people that fit on a bus. In Boston, Massachusetts, for example, there was over a mile length of roadway with LOS F (read: bumper to bumper congestion) on four-lane Washington Street from Roslindale Square to Forrest Hills. The City of Boston, as a pilot project, converted a travel lane to a busbike lane, given that buses on the road carry 60 percent of the people moving through the corridor. The pilot project was deemed a success and the project was made permanent. Precedents for this exist around the world and are being implemented more in the U.S. starting in large cities like Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago, New York City, and Seattle. It may be counterintuitive for congested roads, but latest research and evolving best practices suggest bus-bicycle-only lanes can work in existing congested areas because, like in Boston, the overall increase in people-moving capacity of a bus-bicycle lane justifies the conversion from a travel lane.

4.2.1 Bus-Bicycle Lane Bus-bicycle lanes are developed where there is inadequate space for a painted or separated bicycle lane on a bus route. The bus-bicycle lane can be established by converting a general car travel lane to exclusive bus and bicycle use only. Sometimes this conversion occurs after a traffic analysis shows the traffic impact. However, in many cases the existing level of service (LOS) is F and removing a travel lane and add-

92

Bus-Bicycle Only Lane (Washington Street, Boston, MA)