1 minute read

LAND of PLENTY

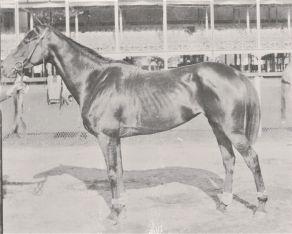

largest Toroughbred nursery.” Haggin began running horses with success at the Bay District track in San Francisco, but soon he also reached to the East for fashionable stock and racing action. In that decade of the 1880s, he purchased and raced (in the East) Salvator and Firenze, both of whom eventually were voted into the Hall of Fame. (Te National Museum of Racing’s Hall of Fame was established in the 1950s in Saratoga Springs, New York.)

Also in the 1880s, Haggin, as owner, won the 1885 Belmont Stakes with Tyrant, as well as the 1886 Kentucky Derby with Ben Ali. Te victory in that Kentucky Derby brought about a strange episode, in which one of the masters of the Turf was at odds with the managers of that growing gem of American racing. As recounted by L.K. Shropshire, managing editor of Te Blood-Horse in 1965, the betting side of Haggin got the better of whatever degree of sporting owner resided in his makeup. Te bombastic ex-Kentuckian from the West arrived at Churchill Downs with many friends and plans for heaving action with the bookmakers, who at that time provided legal and open betting opportunities at the races.

Advertisement

Trouble was that, at about noon of Derby Day itself, Haggin learned “that bookmakers had been barred at the track because of their refusal to pay an increased fee set by Churchill Downs management.” He openly declared that if the situation were not rectifed within 24 hours, he would ship out all the horses he had sent to Churchill Downs, where he had intended to campaign throughout the spring meeting. Shropshire recounted that one of the track ofcials responded to Haggin’s declaration with something along the lines of “who does he think he is?” Te track attitude was relayed to Haggin that if he did not like the situation, he could just go ahead and ship out … “and to hell with him, anyway.”

In the history of the Derby, one doubts other winning owners matched Haggin’s drama on the night of his triumph. He hastily called on his trainer to arrange a speedy departure, and by the next day the Haggin stable was on its way to New York. Although this was an event refecting the dudgeon of one man, the withdrawal was looked upon as a boycott of the rising Kentucky Derby by the powerful Eastern owners of which Haggin was a recognized force.

“Te Derby did not die, but it was defnitely anemic,” wrote Shropshire, who illustrated the situation via mention of frequent three- and four-horse Derby felds over nearly a quarter-century to follow. Moreover, the race almost never attracted contenders from the prestigious Eastern stables during that period.