3 minute read

Museums and collective memories in the 21st century

Searching for stories of resistance

Bianca Saltzman

Advertisement

llook up toward the arched ceiling. Names fill the room. First names, middle names, surnames, Hebrew names. Lost names. But what do they mean to me?

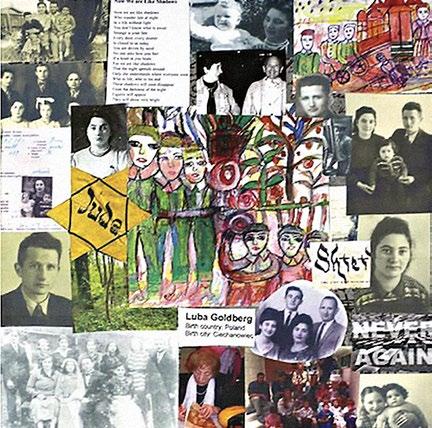

It was possibly my tenth visit to the Centre, but this time, as part of the ‘new normal’ during the global pandemic, my visit was virtual as I navigated the halls of the exhibitions via a mouse and screen. Looking up from my desk, I was greeted by a painting my greatgrandmother had recently completed, hanging on my living room wall. As a Holocaust survivor, painting was her therapy and an expression of the trauma she experienced. It was also a way she passed her memories to her 21 greatgrandchildren, a collective to which I am lucky to belong. From that moment, it was impossible to tour the museum objectively.

The tour began through a hallway filled with the harrowing faces of families: mothers, fathers, children and the unfathomable number of 1.5 million children murdered. Staring into the gleaming eyes of these children, I felt as though they were my family members – the lost siblings of my great-grandmother.

The JHC museum is a fundamental tool in educating a multifaceted society about the horrors experienced by European Jewry in the 1930s and 1940s. It incorporates survivor testimonies into an interactive experience to engage the visitor. The museum aims to ‘package’ the collective memory of the Holocaust for a wide audience consisting of different faiths, nationalities, ages and knowledge. But how can a tragedy be packaged and sold with meaning? How does the individual who already places personal meaning on this historic event interact with the collective memory presented?

This complexity is one I grappled with as I continued to explore the permanent exhibition. The different displays illustrate significant events and places, including Kristallnacht, the infamous Lodz and Warsaw Ghettos and the horrors of concentration camps, importantly circled around a large model of Treblinka.

Faced with what I saw, I could not help but feel disconnected and conflicted by the difference between the collective memory on display and my personal inherited memories. I could not help but long for images of Partisans – images depicting them hiding in the forests of Poland, without shoes, trudging through icy fields; of confrontations with Nazi officers; and Partisans with guns. Although not a typical or public memory of the Holocaust, it is the private and collective memory of a group of survivors that includes both my great-grandparents, Luba and Chaim Goldberg.

Where are the testimonies of rebellion showing the strength and perseverance of survivors? Where is the video of my greatgrandfather explaining how he and his brothers blew up train tracks that were transporting ammunition to Nazi soldiers. These individual stories were hard to find in the collective narrative.

How can a museum aimed at educating such a wide audience adequately detail all the different experiences, many of which confuse and challenge the collective memory and victim narrative that has become synonymous with Holocaust memory?

As a third-generation descendant of survivors harbouring the weight of inherited trauma, I was able to see both the flaws and strengths of a tour through the museum. Not all stories – including my great-grandparents’ more atypical experiences – can be found in a museum. Although I was unable to find my own personal story during my virtual tour, I appreciate the incredible and difficult responsibility the museum bears in acting as the pillar of Holocaust education for both the Jewish and broader Melbourne community.

Luba Goldberg’s Partisan identity card.

Source: Organization of Partisans,

Underground and Ghetto Fighters website Collage of Luba Goldberg’s paintings and photos

Bianca Saltzman completed this reflection as part of her course in History at Monash University.