INNOVATION

Scientists pull living microbes, possibly 100 million years old, from beneath the sea By Elizabeth Pennisi

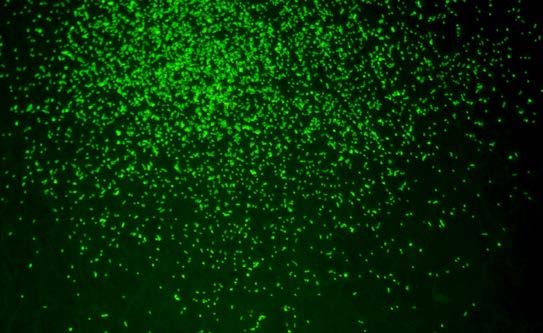

Microbes buried beneath the sea floor for more than 100 million years are still alive, a new study reveals. When brought back to the lab and fed, they started to multiply. The microbes are oxygen-loving species that somehow exist on what little of the gas diffuses from the ocean surface deep into the seabed.

completely lacking the nutrients needed for survival. When they extracted cores of clay and other sediments from as deep as 5,700 metres below sea level, they confirmed the samples did indeed contain some oxygen, a sign that there was very little organic material for bacteria to eat.

The discovery raises the “insane” possibility, as one of the scientists put it, that the microbes have been sitting in the sediment dormant, or at least growing slowly without dividing, for eons.

To explore what life might be there, Morono’s team carefully extracted small clay samples from the centres of the drilled cores, put them in glass vials, and added simple compounds, such as acetate and ammonium, that contained heavier forms — or isotopes — of nitrogen and carbon that could be detected in living microbes. On the day when the group first “fed” the mud samples with these compounds, and up to 557 days later, the team extracted bits of clay from the samples and dissolved it to spot any living microbes — despite the lack of food for them in the clay.

The new work demonstrates “microbial life is very persistent, and often finds a way to survive,” says Virginia Edgcomb, a microbial ecologist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution who was not involved in the work. What is more, by showing that life can survive in places biologists once thought uninhabitable, the research speaks to the possibility of life elsewhere in the Solar System, or elsewhere in the universe. “If the surface of a particular planet does not look promising for life, it may be holding out in the subsurface,” says Andreas Teske, a microbiologist at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, who was also not involved with the new study.

The work was challenging. Typically, there are at least 100,000 cells per cubic centimetre of seafloor mud. But in these samples, there were no more than 1,000 bacteria in the same amount of sediment. So, the biologists had to develop specialised techniques such as using chemical tracers to detect whether any contaminating seawater got into the samples and developing a way to analyse very small amounts of cells and isotopes. “The preparation and care needed to do this work was really impressive,” says Kenneth Nealson, an environmental microbiologist retired from the University of Southern California.

Researchers have known that life exists “under the floorboards” of the ocean for more than 15 years. But geomicrobiologist Yuki Morono of the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology wanted to know the limits of such life. Microbes are known to live in very hot or toxic environments, but can they live where there is little food to eat?

The added nutrients woke up a variety of oxygenusing bacteria. In samples from the 101.5-millionyear-old layer, the microbes increased by four orders of magnitude to more than 1 million cells per cubic centimetre after 65 days, the team reports in Nature Communications.

To find out, Morono and his colleagues mounted a drilling expedition in the South Pacific Gyre, a site of intersecting ocean currents east of Australia that is considered the deadest part of the world’s oceans, almost www.graduatehouse.com.au

24