An Application of Intelligence: David Toren’s Story This piece was originally published in Holocaust Remembered, Vol. 4 in 2017.

D

avid Toren’s 1939 escape to Sweden from the German city of Breslau (now Wroclaw) on the Kindertransport separated him from his older brother, Hans Peter. While David took refuge in Sweden, Hans Peter had gone ahead, arriving in England one day before World War II began. The Toren parents had information on David’s whereabouts, but did not know where their firstborn was. At age 14, David RACHEL cleverly devised MONTGOMERY HAYNIE (OBM) a ploy that got

information past Nazi censors, tipping his parents off as to Hans Peter’s location. For his ploy, he turned to an encyclopedia. “I knew we both had copies of a single volume encyclopedia published by Knaur. I told my parents in a letter: ‘I do not want t o forge German, so I am memorizing it, going entry by entry in the encyclopedia. I am now up to Leibzins.’ My father realized something was hidden in that message. The next entry was Leister, a university town in England. From my

22

HOLOCAUST REMEMBERED |

reference my parents knew Leister was the town my brother was in and were able to figure out the rest.” More than seven decades later, Toren still cherishes his father’s responding letter of praise, calling him smart for such an application of intelligence. He also remembers the long and troubling train ride from his native Germany to an unknown Sweden, a trip during which the teenage boy held on his lap someone’s baby, entrusted to him. As the train rumbled across Europe, he reflected on the life being left behind. “In our community, it was my father who organized the Kindertransport. The seat I took had been promised to a friend who had left our community with his family, destined for the Dominican Republic.” Toren explained that country’s then-president, Rafael Trujillo, believed

accepting German Jews who had professional credentials would help improve the intellectual fiber of the country. The exodus of both brothers took place in 1939, Toren said, “… and my parents were still alive. They were killed March 4, 1943, in the gas chambers at Auschwitz.” Toren managed to hang onto the iconic encyclopedia through tumultuous war times, followed by international moves, service in the Israeli military and, eventually, immigration to the United States. Unfortunately, he cannot show readers what that reference book looked like. “I kept it with me all those years,” explained Toren, who at age 90 still holds sway at the Manhattan law firm on whose letterhead his name is listed. Throughout his professional life, he practiced intellectual property law. “The Knaur Encyclopedia was in my office on the 54th floor, North Tower, World Trade Center on 9/11, the day Bin Laden struck.”

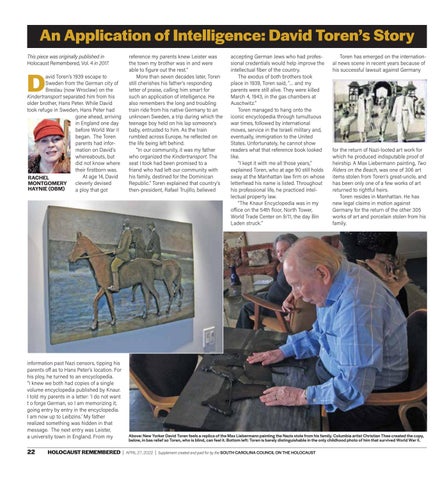

Toren has emerged on the international news scene in recent years because of his successful lawsuit against Germany

for the return of Nazi-looted art work for which he produced indisputable proof of heirship. A Max Liebermann painting, Two Riders on the Beach, was one of 306 art items stolen from Toren’s great-uncle, and has been only one of a few works of art returned to rightful heirs. Toren resides in Manhattan. He has new legal claims in motion against Germany for the return of the other 305 works of art and porcelain stolen from his family.

Above: New Yorker David Toren feels a replica of the Max Liebermann painting the Nazis stole from his family. Columbia artist Christian Thee created the copy, below, in bas relief so Toren, who is blind, can feel it. Bottom left: Toren is barely distinguishable in the only childhood photo of him that survived World War II. APRIL 27, 2022

|

Supplement created and paid for by the SOUTH CAROLINA COUNCIL ON THE HOLOCAUST