17 minute read

Feature

AT ITS MOST BASIC AND

foundational level, an artistic movement is a shift in ideological persuasion. The disposition of the field is contrary to some position and a group, or many groups, will push back against it.

Advertisement

But I would argue, however, that there is a fractal nature to ideologies, that many are occurring in many disparate places. Therefore an artistic movement’s philosophical architecture is formed by the expansion or addition of its ideology into the prevailing culture, as well as the interactions that occur as a result.

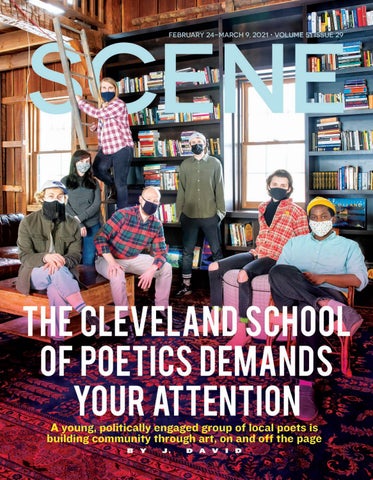

This is precisely what’s happening in Cleveland, where there is an emerging cohort of young poets interested in writing outside of the institution. Their poems are ecstatic, inventive, and challenge the poetic establishment in ways reminiscent of The New York School. As a group, they prioritize collaboration, innovation, and service to the community. These poets, to name some, include Noor Hindi, Kevin Latimer, Brendan Joyce, Geramee Hensley, Katy Ring, DT McCrea, Angelo Maneage and Matt Mitchell.

Explicitly political and interested in dismantling the prevailing culture, The Cleveland School has already established a multitude of opportunities for the community to engage in poetry — The Starlight Elsewhere Reading, This Series Is Not on Netflix, the Joyland events, and more. In addition, their work extends to creating opportunities for writers themselves: founding independent literary journals that pay their writers, like Flypaper; running workshops for writers outside of the academy; engaging in a plurality of mentorship positions; creating Grieveland, a radical poetry press whose practices include paying authors 70% of each book sold; and the formation of The Cleveland Review of Books, run by Billy Lennon — one of the few regional book reviews paying authors professional rates and focusing on small presses.

Though the individual poets within the cohort differ in subject matter, their philosophical underpinnings all include the intent to dismantle the racist capitalist hetero-patriarchy and its associated systems. On the whole, the group believes in Leftist politics along with imagining and building better futures for marginalized communities. Their poetics transparently communicate this.

Noor Hindi, in her poem “Fuck Your Lecture on Craft, My People Are Dying,” observes the following:

Her poetics, while at times mistaken for a poetics of witness, does something far more useful — it participates. Hindi’s poetry engages in a decolonization of language and imagery as is clearly evidenced in the above section. A journalist by trade, Hindi spent the summer covering protests throughout Northeast Ohio with an incisive purpose of reframing the way media reports on society and illuminating the ways in which the journalistic endeavor has fallen short. This purpose leaks into her poetry as well (“Breaking News”):

In interviews, I frame my subject’s stories through a lens to make them digestible to consumers. I become a machine. A transfer of information. They become a plea for empathy, an oversaturation of feelings we’ll fail at transforming into action. What’s lost is incalculable. And at the end of summer, the swimming pools will be gutted of water. And it’ll be impossible to swim.

Hindi’s poems concern themselves with a politic of belonging, what constitutes home, decolonization, and reclamation of spaces.

In a similar vein, Geramee Hensley’s work examines the particulars of relationships — whether that be our relationship to a nation, our relationships with others, or our relationships with ourselves. While Hindi’s poetry exists often as an elevated lingual narrative, straight-forward and interested in conveying information, Hensley’s is experimental and variegated, intent on a poetics of excess and generosity (“One Million Pound Cloud”): BRENDAN JOYCE (he/him) is a busboy from Cleveland, Ohio. His poems have appeared in Protean Magazine and the Johannesburg Review of Books. He is the author of Character Limit (Grieveland, 2019) and Love & Solidarity (Grieveland, 2020).

even the moon

The breeze through the sycamore trees’ sickly leaves that screams worsening working conditions, the squirrel taunting the cat from its clicking perch, the possums hunting rats below in the arson lot, the rats getting hunted, the cloud of bats rising from the school’s roof into October orange cloud cover, the spider sewing its night against a security light, the raccoons casing the attic windows, the millipede ducking a stream of piss in the urinal, the mouse ripping its leg off in the glue trap, the dog singing its song to the whole block of dogs, even the moon in its sorry state of endless retort — hates cops too, you are not alone. The forest, my comrade, whispers: “I am full of cops. I am on fire. They have names & addresses & a growing list of co-conspirators, go, find them. Settle my debt. Say my name.”

MATT MITCHELL (he/him) is an intersex chump getting pummeled by his own carbon footprint in Columbus, Ohio. His work is currently, or soon will be, sleeping on the pull-out couches of Hobart Pulp, The Missouri Review, Bat City Review, The Boiler, and others. He wrote The Neon Hollywood Cowboy (Big Lucks, 2021) and tweets @matt_mitchell48.

The Last Great American Blockbuster

Say neon. MTV. Cocaine. Cut it by telling me how much of a monarch butterfly beautiful

in New York air you are. Tell me how much it hurt you

when Wham! broke up. The problem with iconography

is how I want to swallow all of it, DeLorean myself

back into its outdated orbit.

I dream of a time when cracking knees only means you can’t dance anymore.

If we could all go back, I’m sure we wouldn’t take losing our mothers in Times Square gift shops for granted.

We will walk through the gardens of thick hair thinning into mullets

and come out as electric New Coke signs like lighthouses.

Intersex bodies were just bodies, our hearts yellow as flux capacitors.

When Ric Ocasek says who’s gonna pick you up when you fall and you learn how

there is a blade cutting voice in every man’s throat.

I promise you, I am dreaming of living in a neon decade —

one where everything that is wrong with me did not yet have a name.

Hello I have a bigger knife, it is growing now and I don’t know how to make it stop. Soon it will outgrow my hand then cleave whatever is in front of it…

Imagine you work for a living, imagine you have more than you need to live and someone says hello I have a knife and I won’t stab you for resources. Imagine a person attempting to delay their death by holding a knife and saying they deserve to live. Imagine what they were denied so someone you don’t know can own a private jet…

Suppose a private jet is a knife…

The ways in which this Cleveland School harkens back to the New York School are interesting and informative.

That school — a group of poets, dancers, painters, and musicians finding themselves in close proximity during the 1950s and ’60s in New York City — was, rather than a cadre of scholastic prominence, a loose association based on co-operation in similar fields around similar principles. The New York School, to put it as simply as possible, was a group of friends building community around art.

Their communal artistic interests were as varied as their members, and poets such as Barbara Guest, James Schuyler, Kenneth Koch, Frank O’Hara and Alice Notley found themselves collaborating with experimental painters like Jackson Pollock and Willem DeKooning. Their poems also interested themselves with experimentation and alternate avenues of presentation, which found the artists surveying everyday moments, inserting levity and humor into work, consecrating the personal and intimate, and centering conversations with pop culture. They loved using quotations and names in their work, enjoyed documenting personal interactions, and stirring conversation between disciplines.

The poets in the group lived not simply non-normative lives, but antinormative lives: John Ashbery and Frank O’Hara were explicit about their queerness in their work and lifestyles, Joe Brainard curated a practice of faux-naivete, Alice Notley fashioned for herself a poetry of disobedience and a freedom of sexuality that was at that time a radical notion, and other members of the group participated in the construct of deviance in their own ways.

It was, in many ways, an island of misfit toys, but together became one of the most prominent groups of poets and artists in modern history. And though fame followed, it wasn’t that these poets became widely lauded and admired which made the movement special; it was their interest in community and collaboration.

Here, and now, it’s also what has separated and distinguished the Cleveland School. Take for example the work of Kevin Latimer, another experimental poet working in concert with Hindi and Hensley. He, along with Brendan Joyce, both of whom have long histories of organizing and activism, founded Grieveland — an independent poetry press focusing on radical art while avoiding labor exploitation and paying its authors a higher percentage of sales than any other press in the country.

Outside of the work done with Grieveland, Latimer is a prolific writer. His debut, ZOETROPE, formally restless and adventurous, takes on the task of reimagining grief, lineage, and the future (“TO THE BOYS IN THE WOUND IN THE GROUND”):

a hole opens up in the ground. no one dares go near it. they call the site condemned. little did they know in the depths of the night, boys dance casually around the hole’s iris; praying in ritual. praying for the sun. for new beginnings. they pray for the rain to fall & dance off their fingertips & fall into the nothing. every night these boys pray…

Latimer’s work deals with disaster — personal and societal — creating a compendium of imagistic renderings that collaborate with each other in an effort to create new realizations and futures (“NOTES”):

GOD: what are they doing up there? BOY: surveying. GOD: for what? BOY: light.

Whereas Hensley and Latimer choose to enact a broad and expansive poetics, Hindi and Joyce carry a thoughtful and tactful specificity into their work. They are interested in observing and naming, in uncovering narratives that center everyone being silenced. Joyce is a master of poignant specificity, of drawing connections, elucidating within his work the architecture of our oppressions (“WEEKLY CLAIMS”): kill faster…

The workplace & unemployment compensation are different sides of the same grave…

KEVIN LATIMER (he/him) is a poet from Cleveland, Ohio. he is co-director of grieveland, a poetry project. his recent poems can be found in Jubilat, Passages North, Hobart, Poetry Northwest & more. his plays have been produced by convergence-continuum. find him at @likelykevin.

SQUEEZE GENTLY

The light is a place where i can re-use drugs & there are pillows under my head in the bed of my cell. where there’s no jail. where my name spoken under the muzzle of a gun inspires laughter, not fear. where the bears can use the grocery store as they please & where my sister, dusting nestled dirt off her knees, holds me for the first time since i was five. the light, loud as it is, audacious as it is; where there’s a fire in my mouth, where i cough & we all turn to ash. where we build new worlds; riding rafts down the sink drain on a summer morning. Oh little-us, oh vengeful us, where is the salt under your lip? where is the filament? where does the sinkhole begin. In the light, i jump out of a baby’s mouth. i want to be born again. like salt on the cracked road; tires ripped & torn to shreds, car soaring over the river; bright light in my eyes turning everything white for days. my eyes clear up & now a tall man in the desert stands over me holding a can of gasoline. crumpled, i offer myself to him, tongue out. i wish i knew more about planes. & about love, the whistling in my ears, the real silence. The light, the light, bright slate, yet nothing, yet wedding bells, diamond rings, cigarette halos billowing over the creek. God arriving like he always does: a hug, warm hands, all of my dead family behind him, grinning. The light is a place where there is no joy & no pillows & no jails & no cocaine & no hashtags & no sports & no nostalgia & noprotests & no war & no balconies & no dead ___s & no more books about dead ___s & no idols & no rafts & no banks & no audience & no stage & make up & no applause & no anxiety & no tears & i’m just so tired of talking about this again.

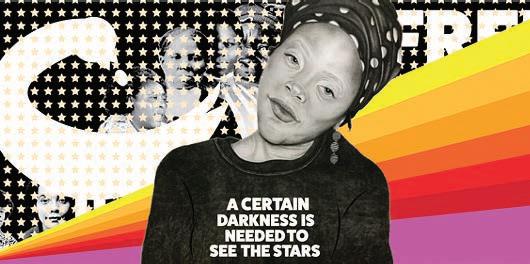

NOOR HINDI (she/her) is a Palestinian-American poet and reporter. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in POETRY, Hobart and Jubilat. Her essays have appeared or are forthcoming in American Poetry Review, Literary Hub, and Adroit Journal. Hindi is the Equity and Inclusion Reporter for The Devil Strip Magazine. Visit her website at noorhindi.com.

Fuck Your Lecture on Craft, My People Are Dying

Colonizers write about flowers. I tell you about children throwing rocks at Israeli tanks seconds before becoming daisies. I want to be like those poets who care about the moon. Palestinians don’t see the moon from jail cells and prisons. It’s so beautiful, the moon. They’re so beautiful, the flowers. I pick flowers for my dead father when I’m sad. He watches Al Jazeera all day. I wish Jessica would stop texting me Happy Ramadan. I know I’m American because when I walk into a room something dies. Metaphors about death are for poets who think ghosts care about sound. When I die, I promise to haunt you forever. One day, I’ll write about the flowers like we own them.

These poets, like the New York School, also find themselves actively collaborating with visual artists, among them Angelo Maneage and Matt Mitchell, both of whom are exciting poets as well. Mitchell’s work, like that of Frank O’Hara and many of the other New York School poets, integrates pop culture along with tender poems directed at the rest of the cohort. His work demonstrates the ways in which art impacts the prevailing culture and seeks to work in the liminal spaces drawn between disciplines. There is a reckless abandon in Mitchell’s poems, one that enters with its hair ablaze and begins ripping apart the room until the discovery of something monumental (“MERRY CLAYTON BURIED HER CHILD IN A THROAT OF STARS”):

Merry Clayton carved a whole life out of a song she never listened to. Because that is what it’s like to inhabit the space of someone else’s grief: to fear hearing your own voice echo off the walls.

Though its members are colored by their particular obsessions and styles, the connective tissue among the Cleveland School poets is vast and encompassing. It includes a desire to re-communicate histories honestly, centering excluded voices and philosophies; reimagining better futures for excluded and oppressed communities; prioritizing activism and community-building; and fostering a culture of collaboration. But above all else, the group demonstrates a palpable understanding of the personal as political, this becoming the propulsion for their poetics.

The personal has always been political, and this is something the New York School believed. But don’t take their word for it, examine the facts — it is hard to escape notice that we live in a country inextricably tied in a global capitalist system devolved into corporatism; a country whose democracy is influenced by western values and individualist mores; a country infiltrated by perpetual data and technological monitoring at every incidence of opportunity. Because of this, I find myself unable to believe in any distance between the personal and political. We are an irreducible part of the system and take part in the corporate — whose influence in the political is both insidious and understandable in a capitalist system. This reaches into each aspect of our lives: when we wake, how we choose to rest, what we devote our time and energy to, what we spend our money on; these, just a miniscule sampling of our existence, will find ways to impact who is elected, fluctuations in various spectrums of personal rights, and even which people have what rights and when. Every action we take has political ramifications.

How can any poetry exist outside of this system? It can’t.

Poetry, though it resists commodification, and though it be an art, will never be apolitical. Whether you believe it to be an alternative form of knowing or just a cute occurrence of word-play, poetry will enter the world through an individual mind. And that mind is colored by its perceptive capabilities, its memories, and its societal placement. Each person brings to the table their socioeconomic standing; ANGELO MANEAGE (he/him) is an artist and poet in Cleveland, Ohio. His work is on or in poets. org, Hobart, jam & sand, around. His plays have been put on by convergence continuum. Visit him at angelomaneagethewebsite.com.

PICKED UP ZOETROPE FROM KEVIN’S HOUSE

First appeared in The Hunger.

By the blue chair I climbed to grab the future It was in a PO box that was unlocked So I backed up and jumped pretty high in but landed in the petunia bed Who grows so much

Red and white in the middle of summer my nipples hairless in the driveway I climbed to the roof and jumped into a bucket of ribbons or a mail truck one of those And had gotten red juice all over my shirt I decided I would work for the living And then that I would never work for this government a blue chair

The rim of a tea ball game that outskirt where I like to sit in and get kissed At I hear a ringing and I think it is the doorbell TO THE OPEN BOX I climb the chair As a child I am far away from the baseball when it hits me I went with the boys

To prom I puked all over ryan’s sister and the police arrived and justin fell over He has leukemia later on anyway he got right back up and they arrest craig We hold our own and wait to share a lawyer For justice I climb the elevator shaft to the lawyer›s house and swing down

The rope he hands me full of special knots like bowlines and sheet bends I move my body through the blue into the box

I lick the stamp or wait no what am I oh yeah I am climbing Into the sky and eating the poison it does not filter out and spitting it out again And eating the sauce with the daffodils A flavor we share both of us

Tape up the box with my body inside I thought about the echos in here there are echos in here in this small box Its depth it had to have been a thousand feet or two And there IS an ocean I am falling past tons of whales

And before I hit the ground the whales sing to me they sing YOU ARE BLUE LIKE US WE SING FOR JOY TO FILL THE AIR WE FALL INTO

MEGAN NEVILLE (she/her) is an educator and writer. Her work has been published or is forthcoming in The Academy of American Poets (Poets.org), Cherry Tree, Pleiades, wildness, Cream City Review, Glass: A Journal of Poetry, The Boiler, McSweeney’s, Lunch Ticket, Gordon Square Review, and elsewhere. She is a poetry reader for Split Lip Magazine and was a finalist in Write Bloody’s 2019 book contest. She lives in Tremont with her spouse and three cats. Find her online at megannevillepoetry.com.

TO THE WOMEN WHO SURROUNDED THE PENTAGON

First appeared in Gordon Square Review.

with their sturdy legs, milk-flat breasts, & embroidered panels of muslin –

who deployed on overnight greyhounds leaving their children in ohio while

they took on world leaders with needles & thread greased with beeswax – lost in a nuclear war, dissolved by splitting

atoms as miraculously as they’d conceived us. we ate pizza & watched nickelodeon

while they wedged themselves before any lawmakers or gods who’d hear

prayers for non-proliferation. that late summer afternoon in 1985 they

so believed in their fabric activism – thought by unfolding & tying together out of the world & make peace.

oh, mothers of that generation: the world is still a vortex of hate.

those men did not listen or act & you returned home to trim crusts from bread.

we’ve grown up & as you’d hoped, most were not lost –

but we’ve seen believing isn’t enough. blanket the world. blanket as a noun &

verb. cover the earth with your stitchery, but the feet always find their way out.