Peddler of Ideas BY JAIMEE LEIGH JOROFF

A

Amos Bronson Alcott was about to drown. How could this be happening? Born on November 29th, 1799, he was the eldest son of a poor farmer from Wolcott, Connecticut, and he was only 19 years old! Straining to keep his head above water, Bronson could see his bag on the shore with the $100 he was bringing home to help pay his father’s debts. And what of his mother, who taught Bronson his ABCs by having him trace them on her dirt parlor floor, her warm memory in stark contrast to the rigid teacher in the one room schoolhouse Bronson attended until leaving at age 10 to work full-time on his father’s farm. He had continued to love 18

Discover CONCORD

| Fall 2020

reading and learning, amassed books, and dreamed of becoming a teacher. At 17, he passed his teacher’s certification, but no teaching positions had yet opened for him and he’d taken to the road as a peddler, joining a “peddling fever” of New England men selling trinkets and household wares through Southern states. On this May morning, in the company of another young peddler, Bronson was returning from his second trip south. Near Williamsburg, Virginia, the two stopped to bathe in the James River. A sudden rip current seized them! Petrified, Bronson’s companion grabbed him, dragging Bronson down until

death loosened his grasp. Now, fighting the current alone, perhaps a line from Bronson’s favorite novel, Pilgrim’s Progress, screamed through his head, “What shall I do to be saved?” I shall kick, and I shall swim, and I shall claw my way to shore. And with that, this grandson of an American Revolutionary War soldier saved himself from the James River. After three more peddling expeditions, Bronson finally attained a teaching job. From 1823-1828, he taught school in Connecticut, applying unconventional methods foreign to the time. Influenced by the Swiss educator Pestalozzi, who promoted individualized, moral, and harmonious education, Bronson believed that children had their own minds and should be taught to think rather than be forced to memorize. He saw inherent goodness in each child, and disdained corporal punishment and the sedentary schools of old. He encouraged students to get out of chairs, act out lessons, and exercise. He also started evening classes for students’ parents. Despite being recognized by area newspapers as a school “of a superior and improved kind” and perhaps the best common school in the United States, some regarded his radical methods with fear and suspicion and his school closed in 1828. A lifetime of educational pursuits followed. Marrying Abigail May in 1830, Bronson moved to Boston, MA, where, with the teaching assistance of Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, (the brilliant sister-inlaw of Nathaniel Hawthorne), he opened and ran The Temple School. In an age where “children should be seen and not heard”, Bronson continued to ask questions of the children, encouraging their self-expression. His methods began to garner public notice and controversy, particularly when Bronson initiated a series of “Conversations on the Gospels” with his young students. For the families, this was an outrageous entering of religion reserved for the church. Backlash against Bronson was fierce, but the Bostonian minister Ralph Waldo Emerson came to his defense calling Bronson a Socrates of his time. Although Bronson was forced to close the Temple School, he began a lifetime friendship with Emerson, which

Photos courtesy of Barrow Bookstore

Amos Bronson Alcott:

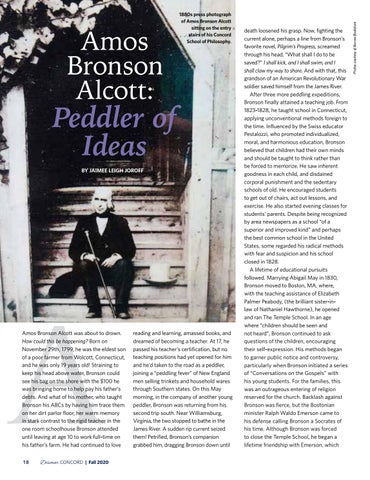

1880s press photograph of Amos Bronson Alcott sitting on the entry stairs of his Concord School of Philosophy.