Around Town Community n Kevin Nelson Some days in this life are harder to bear than others. For Evan Guillot, January 31, 2015 was as hard as they come. That was the anniversary of Sergeant Stacey’s death. Three years earlier, while leading a patrol of Marines searching for enemy Taliban in Helmand Province in Afghanistan, he stepped on an improvised explosive device that took his life. He was 23. “Sgt. Stacey was the perfect Marine,”

HERO ON THE HILL the story behind a memorial

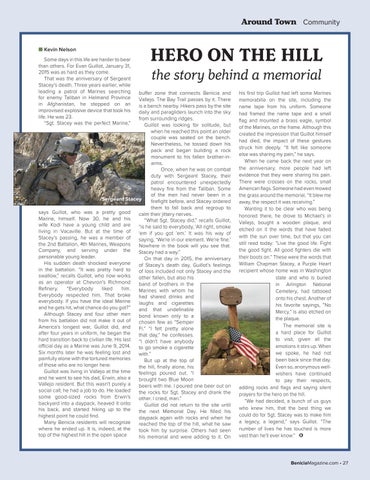

buffer zone that connects Benicia and Vallejo. The Bay Trail passes by it. There is a bench nearby. Hikers pass by the site daily and paragliders launch into the sky from surrounding ridges. Guillot was looking for solitude, but when he reached this point an older couple was seated on the bench. Nevertheless, he tossed down his pack and began building a rock monument to his fallen brother-inarms. Once, when he was on combat duty with Sergeant Stacey, their patrol encountered unexpectedly heavy fire from the Taliban. Some of the men had never been in a Sergeant Stacey firefight before, and Stacey ordered them to fall back and regroup to says Guillot, who was a pretty good calm their jittery nerves. Marine, himself. Now 30, he and his “What Sgt. Stacey did,” recalls Guillot, wife Kodi have a young child and are “is he said to everybody, ‘All right, smoke living in Vacaville. But at the time of ‘em if you got ‘em.’ It was his way of Stacey’s passing, he was a member of saying, ‘We’re in our element. We’re fine.’ the 2nd Battalion, 4th Marines, Weapons Nowhere in the book will you see that. Company, and serving under the Stacey had a way.” personable young leader. On that day in 2015, the anniversary His sudden death shocked everyone of Stacey’s death day, Guillot’s feelings in the battalion. “It was pretty hard to of loss included not only Stacey and the swallow,” recalls Guillot, who now works other fallen, but also his as an operator at Chevron’s Richmond band of brothers in the Refinery. “Everybody liked him. Marines with whom he Everybody respected him. That broke had shared drinks and everybody. If you have the ideal Marine laughs and cigarettes and he gets hit, what chance do you got?” and that undefinable Although Stacey and four other men bond known only to a from his battalion did not make it out of chosen few as “Semper America’s longest war, Guillot did, and Fi.” “I felt pretty alone after four years in uniform, he began the that day,” he confesses. hard transition back to civilian life. His last “I didn’t have anybody official day as a Marine was June 9, 2014. to go smoke a cigarette Six months later he was feeling lost and with.” painfully alone with the tortured memories But up at the top of of those who are no longer here. the hill, finally alone, his Guillot was living in Vallejo at the time feelings poured out. “I and he went to see his dad, Erwin, also a brought two Blue Moon Vallejo resident. But this wasn’t purely a beers with me. I poured one beer out on social call; he had a job to do. He loaded the rocks for Sgt. Stacey and drank the some good-sized rocks from Erwin’s other. I cried, man.” backyard into a daypack, heaved it onto Guillot did not return to the site until his back, and started hiking up to the the next Memorial Day. He filled his highest point he could find. daypack again with rocks and when he Many Benicia residents will recognize reached the top of the hill, what he saw where he ended up. It is, indeed, at the took him by surprise. Others had seen top of the highest hill in the open space his memorial and were adding to it. On

his first trip Guillot had left some Marines memorabilia on the site, including the name tape from his uniform. Someone had framed the name tape and a small flag and mounted a brass eagle, symbol of the Marines, on the frame. Although this created the impression that Guillot himself had died, the impact of these gestures struck him deeply. “It felt like someone else was sharing my pain,” he says. When he came back the next year on the anniversary, more people had left evidence that they were sharing his pain. There were crosses on the rocks, small American flags. Someone had even mowed the grass around the memorial. “It blew me away, the respect it was receiving.” Wanting it to be clear who was being honored there, he drove to Michael’s in Vallejo, bought a wooden plaque, and etched on it the words that have faded with the sun over time, but that you can still read today: “Live the good life. Fight the good fight. All good fighters die with their boots on.” These were the words that William Chapman Stacey, a Purple Heart recipient whose home was in Washington state and who is buried in Arlington National Cemetery, had tattooed onto his chest. Another of his favorite sayings, “No Mercy,” is also etched on the plaque. The memorial site is a hard place for Guillot to visit, given all the emotions it stirs up. When we spoke, he had not been back since that day. Even so, anonymous wellwishers have continued to pay their respects, adding rocks and flags and saying silent prayers for the hero on the hill. “We had decided, a bunch of us guys who knew him, that the best thing we could do for Sgt. Stacey was to make him a legacy, a legend,” says Guillot. “The number of lives he has touched is more vast than he’ll ever know.”

BeniciaMagazine.com • 27