5 minute read

DID YOU KNOW?

DID YOU KNOW?

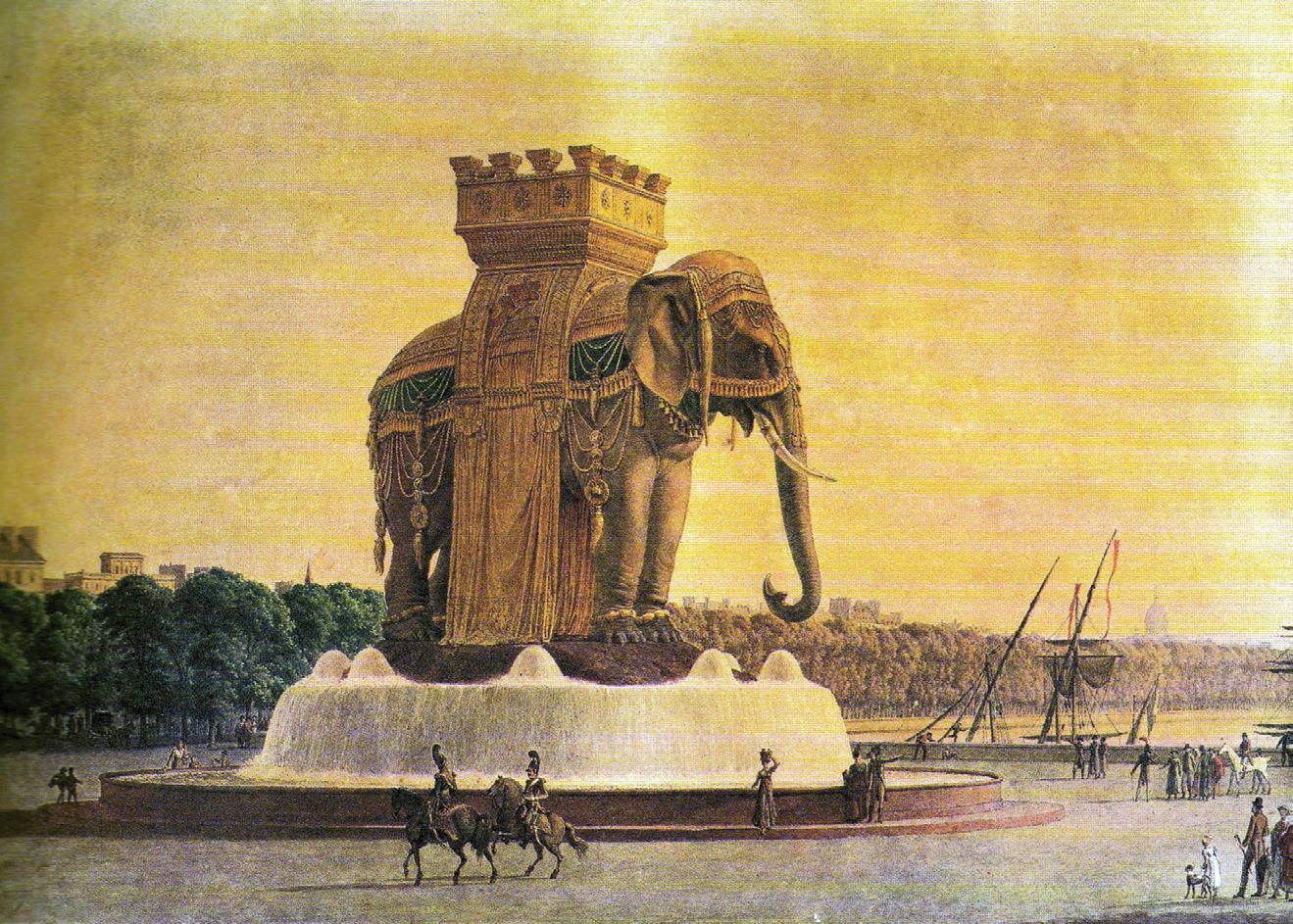

Plaster of Paris - how Napoleon’s white elephant became the city’s elephant in the room

The elephant in the room might also be a white elephant. If you step outside of the room to gain perspective, you might see the elephant. And, if it is too hard to deal with in one go, you might eat the elephant one bite at a time. Elephants loom large in the imagination and have given the English language several memorable idioms.

A white elephant conjures images of grand, often misguided, ambitions. It speaks of enormous undertakings, costing a king's ransom, yet ultimately delivering little more than an oversized burden. Such a creature, both literal and metaphorical, stood for decades in the heart of Paris, a monument to revolutionary zeal, imperial hubris, and, finally, a tragic, almost comical neglect.

In the first decade of the nineteenth century, revolutionary fervour in France had been tamed and channelled under the decisive rule of Napoleon Bonaparte. Like many conquering heroes before him, Napoleon wanted to leave lasting reminders of his glorious rule. The Arc de Triomphe and the Colonne Vendôme still stand and proclaim ‘la gloire’.

The Place de la Bastille, the very crucible of the Revolution, was ripe for Napoleonic transformation. Here, the infamous prison of the Bourbon kings had been dismantled brick by brick. And it was here, on that a new, equally colossal symbol was to rise.

Napoleon’s initial vision was truly colossal: a bronze elephant, four times life-size, spouting water from its trunk. This was not merely an aesthetic choice; it was imbued with potent symbolism. The elephant, a creature of immense strength and enduring memory, was to represent imperial power and wisdom, a fitting successor to the shattered stones of the old prison. The water, a practical element for the surrounding fountains, also hinted at abundance and prosperity under Napoleonic rule. The cornerstone was laid in 1812, and the initial plaster model, a truly imposing beast, soon graced the square.

This plaster behemoth, intended as a temporary placeholder, was itself a sight to behold. Towering sixty feet high, it commanded attention, its grey mass a stark contrast to the elegant Parisian architecture surrounding it. For a brief period, it was a source of national pride, a tangible representation of a future sculpted by the Emperor’s will. However, the tides of fortune, much like the waters meant to flow from its trunk, were about to turn.

Napoleon’s grand plans, like so many of his later campaigns, began to unravel. The disastrous Russian retreat, the subsequent European coalition, and ultimately, his abdication in 1814, meant that the bronze elephant remained an unfulfilled dream. The Bourbons returned, and, with them, a very different set of priorities. The magnificent bronze casting never materialised. Instead, the plaster model, a testament to an abandoned vision, remained.

And there it stood. For over thirty years, the Elephant of the Bastille became a permanent fixture, not of grandeur, but of urban decay. It was never truly completed, never properly maintained. The elements, indifferent to imperial ambitions, began their slow, relentless work. Rain and frost gnawed at its plaster hide, causing cracks and fissures. Its colossal form became a haven for vermin, a shadowy shelter for the destitute, and a rather pungent landmark for curious tourists. What was once a symbol of power became a grotesque caricature of neglect, a monument to the fleeting nature of glory.

Its decline was documented by contemporary writers, most notably Victor Hugo, who immortalised the elephant in his masterpiece, Les Misérables. It is here, within the elephant’s decaying belly, that Gavroche, the street urchin, finds a temporary home, a poignant metaphor for the forgotten and dispossessed. Hugo’s vivid description of the elephant's decrepitude served to cement its status as a symbol of unfulfilled promises and the stark realities of Parisian poverty.

By the 1840s, the elephant had become the elephant in the room, an eyesore, a public health hazard, and a potent symbol of a past best forgotten. The decision was finally made to demolish it. In 1846, the plaster elephant was systematically dismantled, leaving behind only the circular base that had supported it. The grand imperial vision had crumbled, quite literally, into dust.

The story of the Elephant of the Bastille is more than just a quirky historical anecdote. It serves as a potent reminder of the perils of unchecked ambition and the sometimes-absurd consequences of grand, but ultimately abandoned, schemes. It was a literal white elephant, an expensive and ultimately useless burden, but also a metaphorical one, embodying the transient nature of power and the enduring presence of unintended legacies. Its decay, however undignified, offers a curious and instructive footnote in the long and often eccentric history of Parisian monuments. ν

This article was provided courtesy of Ian Chapman-Curry, Legal Director in the pensions team at Gowling WLG and host of the Almost History podcast.