4 minute read

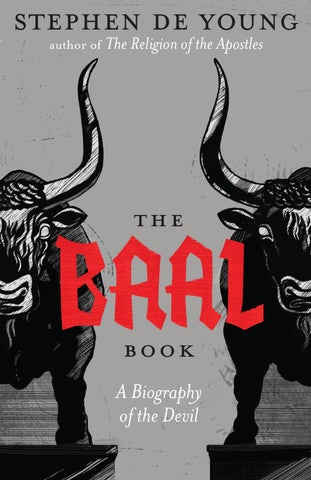

The Baal Book: A Biography of the Devil

Out on Baal

What Should We Make of an Ancient Canaanite God?

This book is a biography of the Devil. In twentieth century scholarship, the common view of the origin of the figure of the Devil or Satan is that it emerged in the Persian period. Following Judah’s exile in Babylon, an alliance of Persians and Medes conquered the Neo-Babylonian Empire, producing the first Persian Empire. Cyrus the Great then allowed the exiles of Judah to return and created the province of Judea. Since much of the Old Testament was either composed or reached its current, edited form in Hebrew or Aramaic during this period, scholars concluded that any changes in Second Temple Judaism leading into the emergence of Christianity were, in whole or in part, the result of Persian influence. Western scholars, vaguely understanding Zoroastrianism as a form of dualism, then argued that the idea of a figure opposed to Yahweh the God of Israel must be an evolution or adaptation of Persian belief in a second, evil god. However, this is not the reality of Zoroastrian self-understanding, which holds that Ahura Mazda has a complicated relationship with an entity described as his shadow.

More importantly, there is simply no evidence, Jewish or Christian, in which the Devil is seen as being equally powerful or eternal along with God. Rather, the Devil—or Satan—is always depicted in Scripture and in Second Temple Jewish and Christian traditions as a rebellious vassal of the true God.

The figure of Baal is consistently portrayed as just such a rebellious servant; he is described by his own worshipers in terms very similar to those used to describe the Devil in Jewish and Christian tradition. He is prominent throughout the Hebrew Scriptures as an adversary of God for the worship of His people. In ancient Near Eastern pagan circles, this rebellion was a revolution with Baal as its hero; it was the first in a long string of victories for which he was worshiped and glorified. But the Hebrew Scriptures consciously recast this story, turning it on its head. Baal is depicted as a failed rebel, defeated and condemned, who nonetheless continues to attempt to steal glory that rightly belongs to the Almighty God. From the Scriptures’ retelling of the Baal myth, the figure of the Devil emerges from the earliest chapters of Genesis to the New Testament’s descriptions of the Evil One.

Modern Archaeology and the Scriptures

The contributions of modern archaeology to the understanding of the Old Testament are a mixed bag in that it’s difficult to see some research as a legitimate contribution. Biblical archaeology in its earliest phase divided into “modernist” and “fundamentalist” factions, more recently described commonly as “liberal” and “conservative,” respectively. In truth, both these factions proceed on modernist presuppositions and principles. This is not the place to enter into a discussion of whether archaeology properly constitutes a science or ought to be conducted by scientific means. But, when approached as a science, both groups have set out to use those

means either to prove or disprove a very literal interpretation of the Hebrew Scriptures.

The Limitations of “Real”

Literal itself is a slippery term. In archaeology, it refers to the idea that what is “real” is that which can be demonstrated to be true through the application of scientific methods to evidence. This means that anything proposed about the past must obey the then-current understanding of the laws of natural science and also correspond to a kind of material reality that could be filmed or photographed. Thus the wisdom and spiritual insights of ancient people regarding the greater meaning of events, their feelings and impressions of them, and the importance of them in the life of nations or people groups are not “real” in this sense. For the liberal scholar, insofar as these larger considerations form the biblical narrative, Scripture is not true, or at least not historical. For the conservative scholar, to imply that these larger considerations of meaning shape the biblical narrative outs someone as a liberal and means that they do not believe that the narrative is true, or at least historical.

The world is not so artificial, so material, or so clockwork as these views require. Someone either loves another person, or they do not. There is no way to test for love. It does not leave, in most cases, conclusive archaeological evidence. Yet it is no less real. A narrative reflecting the author’s subjective views of goodness, beauty, and ethical norms does not render it ahistorical. When an ancient author sees spirits at work in events on earth, this does not mean that the events didn’t happen. Nor is the author’s understanding a claim that these spirits would have been seen with the bodily senses at the time the events occurred. Everyone understands this in day-to-day communications and in reading written records.